Читать книгу Way of All the Earth - Anna Akhmatova - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

‘Who can refuse to live his own life?’ Akhmatova once remarked in answer to some expression of sympathy. Her refusal not to live her life made of her one of those few people who have given dignity and meaning to our terrible century, and through whom and for whom it will be remembered. In relation to her, the politicians, the bureaucrats, the State torturers, will suffer the same fate that, in Akhmatova’s words, overtook Pushkin’s autocratic contemporaries: ‘The whole epoch, little by little . . . began to be called the time of Pushkin. All the . . . high-ranking members of the Court, ministers, generals and non-generals, began to be called Pushkin’s contemporaries and then simply retired to rest in card indexes and lists of names (with garbled dates of birth and death) in studies of his work. . . . People say now about the splendid palaces and estates that belonged to them: Pushkin was here, or Pushkin was never here. All the rest is of no interest to them.’

Pushkin was the closest of the friends she did not meet even once in her life. He helped her to survive the 1920s and 30s, the first of Akhmatova’s long periods of isolation and persecution. Dante, too, was close. And there were friends whom she could meet, including Mandelstam and Pasternak, whose unbreakable integrity supported her own. But no-one could have helped, through thirty years of persecution, war, and persecution, if she had not herself been one of the rare incorruptible spirits.

Her incorruptibility as a person is closely linked to her most fundamental characteristic as a poet: fidelity to things as they are, to ‘the clear, familiar, material world’. It was Mandelstam who pointed out that the roots of her poetry are in Russian prose fiction. It is a surprising truth, in view of the supreme musical quality of her verse; but she has the novelist’s concern for tangible realities, events in place and time. The ‘unbearably white . . . blind on the white window’ of the first poem in the present selection is unmistakably real; the last, from half-a-century later, her farewell to the earth, sets her predicted death firmly and precisely in ‘that day in Moscow’, so that her death seems no more important than the city in which it will take place. In the Russian, the precision is still more emphatic and tangible: ‘tot moskovskii den’—‘that Muscovite day’. In all her life’s work, her fusion with ordinary unbetrayable existence is so complete that only the word ‘modest’ can express it truthfully. When she tells us (In 1940), ‘But I warn you,/I am living for the last time’, the words unconsciously define her greatness: her total allegiance to the life she was in. She did not make poetry out of the quarrel with herself (in Yeats’s phrase for the genesis of poetry). Her poetry seems rather to be a transparent medium through which life streams.

Not that Akhmatova was a simple woman. In many ways she was as complex as Tolstoy. She could reverse her images again and again—a woman of mirrors. ‘She was essentially a pagan,’ writes Nadezhda Mandelstam: like the young heroine of By the Sea Shore who runs barefoot on the shore of the Black Sea; but she was also an unswerving, lifelong Christian. She was one of the languid amoral beauties of St Petersburg’s Silver Age; and she was the ‘fierce and passionate friend who stood by M. with unshakeable loyalty, his ally against the savage world in which we spent our lives, a stern, unyielding abbess ready to go to the stake for her faith’ (N. Mandelstam: Hope Abandoned). She was sensual and spiritual, giving rise to the caricature that she was half-nun, half-whore, an early Soviet slander dredged up again in 1946, at the start of her second period of ostracism and persecution. Akhmatova was not alone in believing that she had witch-like powers, capable of causing great hurt to people without consciously intending to; she also knew, quite simply, that she carried, in a brutal age, a burden of goodness. This is the Akhmatova who, in a friend’s words, could not bear to see another person’s suffering, though she bore her own without complaint.

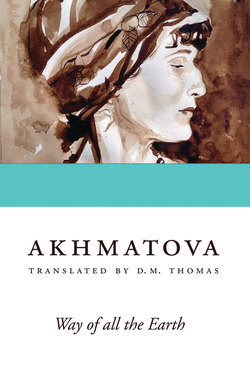

The air of sadness and melancholy in her portraits was a true part of her, yet we have Nadezhda Mandelstam’s testimony that she was ‘a wonderful, madcap woman, poet and friend . . . Hordes of women and battalions of men of the most widely differing ages can testify to her great gift for friendship, to a love of mischief which never deserted her even in her declining years, to the way in which, sitting at table with vodka and zakuski, she could be so funny that everybody fell off their chairs from laughter.’ Her incomparable gift for friendship, and her difficulties in coping with love, are wryly suggested in the lines ‘other women’s/Husbands’ sincerest/Friend, disconsolate/Widow of many . . .’ (That’s how I am . . .) Her love for her son is made abundantly clear in the anguish of Requiem, her great sequence written during his imprisonment in the late 30s; yet she found the practicalities of motherhood beyond her.

In Akhmatova all the contraries fuse, in the same wonderful way that her genetic proneness to T.B. was controlled, she said, by the fact that she also suffered from Graves’ disease, which holds T.B. in check. The contraries have no effect on her wholeness, but they give it a rich mysterious fluid life, resembling one of her favourite images, the willow. They help to give to her poetry a quality that John Bayley has noted, an ‘unconsciousness’, elegance and sophistication joined with ‘elemental force, utterance haunted and Delphic . . . and a cunning which is chétif, or, as the Russians say, zloi.’*1

Through her complex unity she was able to speak, not to a small élite, but to the Russian people with whom she so closely and proudly identified. Without condescension, with only a subtle change of style within the frontiers of what is Akhmatova, she was able to inspire them with such patriotic war-time poems as Courage. It is as though Eliot, in this country, suddenly found the voice of Kipling or Betjeman. The encompassing of the serious and the popular within one voice has become impossible in Western culture. Akhmatova was helped by the remarkable way in which twentieth-century Russian poetry has preserved its formal link with the poetry of the past. It has become modern without needing a revolution, and has kept its innocence. In Russian poetry one can still, so to speak, rhyme ‘love’ with ‘dove’.

Akhmatova herself, with her great compeers, Mandelstam, Pasternak and Tsvetaeva, must be accounted largely responsible for the continuity of Russian poetic tradition. Together, they made it possible for the people to continue to draw strength from them. The crowds who swarmed to Akhmatova’s funeral, in Leningrad, filling the church and overflowing into the streets, were expressing her country’s gratitude. She had kept the ‘great Russian word’, and the Word, alive for them. She had outlasted her accusers: had so exasperated them that, as she put it, they had all died before her of heart-attacks. Mandelstam had perished in an Eastern camp; Tsvetaeva had been tormented into suicide; Pasternak had died in obloquy; Akhmatova had lived long enough to receive the openly-expressed love of her countrymen and to find joy in the knowledge of poetry’s endurance. All four had overcome. The officials of Stalin’s monolith were retiring ‘to rest in card indexes’ in studies of their work. It is a momentous thought. Can it be by chance that the worst of times found the best of poets to wage the war for eternal truth and human dignity?

In this selection of Akhmatova’s poetry I have tried to keep as closely to her sense as is compatible with making a poem in English; and the directness of her art encourages this approach. The geniuses of the Russian language and the English language often walk together, like the two ‘friendly voices’ Akhmatova overhears in There are Four of Us; but they also sometimes clash, and there are times when it is a deeper betrayal of the original poem to keep close to the literal sense than it would be to seek an English equivalent—one that preserves, maybe, more of her music, her ‘blessedness of repetition’. Striving to be true to Akhmatova implies, with equal passion, striving to be true to poetry. When I have found it necessary to depart from a close translation, I have sought never to betray the tone and spirit of her poem, but to imagine how she might have solved a particular problem had she been writing in English.

Together with my previous volume, versions of Requiem and Poem without a Hero,*2 the present selection is intended to be sufficiently large and representative to give English-speaking readers a clearer, fuller impression of her work than has previously been available. Whether or not I have been successful in this, I know that my own gain, from studying her poetry so intimately, has been immense, and beyond thanks, but I thank her.

D.M.T.

Notes

*1 TLS, 16 April 1976.

*2 Paul Elek Ltd (London) and Ohio U.P., 1976.