Читать книгу One Family Under God - Anna M. Lawrence - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

Transatlantic Methodism: Roots and Revivals

The Atlantic world was a crucible of religious exchange in the eighteenth century. The Methodist family flourished in this transatlantic arena as early evangelicals established a missionary project to spread the word, both domestically and universally. The early evangelical movement had three main characteristics: transcendence, sociability, and mobility. Evangelicals repeatedly sought to transcend their physical bodies in order to have a better union with God, and they sought to connect with one another in order to find support for their individual religious journeys. They found sustenance among many different kinds of people, whose only essential commonality was their overriding desire for salvation. The religious family expanded connections between evangelical members who were not related by blood and not necessarily connected by nationality, ethnicity, or race.

Eighteenth-century evangelicals achieved this transcendence and sociability through the expansive print culture and mobility of people circulating throughout the Atlantic world. This mobility was central to how Methodism expanded as a family—from the circuits that kept preachers in constant rotation to the outdoor revivals where evangelicals traveled to meet with each other. Just as evangelicals were itinerant, their language was also mobilized by the increased circulation and production of print material. Methodists spanned the vast distance of the Atlantic through epistolary and print means more commonly than by actually crossing the ocean themselves. The circulation of evangelical discourse formed the basis of their spiritual unity, overcoming the great distance between evangelical groups.

Formative episodes in early Methodist history occurred in England, Wales, Ireland, America, and even on the Atlantic Ocean itself. This organization grew as a transatlantic movement with ideas, discourse, and people crisscrossing the Atlantic throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Methodism was not an English transplant on American soil; it matured within a culture of exchange. Because of founder John Wesley’s charisma and organizational strengths, Methodist histories tend to focus on Oxford or his home of Epworth, England, as the sites of Methodism’s genesis. In some historical narratives, the transatlantic scope of Methodism only arises during the post-Revolutionary period when American Methodist leaders challenged John Wesley’s leadership. But there were important earlier chapters of significant transatlantic cultural exchange. One such period was when John and Charles Wesley undertook an Anglican mission in Georgia in 1735 and put a number of early Methodist social and organizational ideas to the test. Subsequently, in the late 1730s and 1740s, American and English revivalists fed off each other, swapping conversion accounts and methods for evangelizing the transatlantic arena. Transatlantic dialogues occurred between American and English evangelicals and also between European pietists, like the Moravians, and nascent Methodists. Moravianism and the broader transatlantic evangelical culture helped to spark Methodists’ simultaneous concentration on the mission of converting souls and formulating a domestic religiosity, the foundation for the Methodist family.

Origins of Methodism

Any discussion of the origins of a social or religious movement is tricky. A movement does not spring forth fully formed at one point in time; instead, multiple strains coalesce to produce a movement. Still, like any storyteller or listener, we appreciate even a provisional starting point. One date to begin talking about Methodism’s birth might be 1729, when John Wesley, Charles Wesley, and others began meeting in “the Holy Club” at Oxford University.1 Some historians frame the beginnings of Methodism with a biography of Wesley, starting with his birth in 1703, emphasizing his parents’ interesting mix of high church and dissenting strains.2 Some early histories of English evangelicalism choose a very specific beginning, John Wesley’s conversion on May 24, 1738, at “about a quarter to nine,” to be precise.3

Methodism came out of the broader evangelical movement, but it was not the only spoke in that wheel. While he was the primary founder of Methodism, it would be a mistake to locate the genesis of Methodism and its ideas solely in John Wesley. For one, George Whitefield, a fellow member of the Oxford Holy Club, had experienced his own conversion earlier, in 1735, and was a leading itinerant by 1738. Well before John Wesley’s rise, Whitefield was touring throughout the Atlantic world, in the American colonies, England, and Wales. In addition, British evangelicalism began not with Wesley-centered revivals but with Welsh dissenters, who emerged prior to the inception of Methodism. The major formative period for evangelicalism in the British Atlantic world commenced as early as 1714, when there was a small Welsh revival led by Griffith Jones. There were larger numbers of successful revivals after Anglican clergymen Daniel Rowlands and Howell Davies began itinerating in 1735. In 1736, the renowned Welsh preacher Howell Harris started his itinerant preaching career, and he became particularly instrumental in fomenting robust revivals, forming small spiritual societies, and encouraging lay preaching; all these elements eventually became cornerstones of Methodist practice.4

If one links Methodist history to the Welsh revivals and the meetings of the Holy Club, it becomes clear that Methodism began as a collaborative movement, drawing upon a sometimes uncoordinated and contradictory set of leaders and influences. Charles Wesley started the Holy Club in 1729, before his elder brother John became its true leader.5 The club’s structure was less like a cohesive organization and more like a network of associations. The Holy Club was actually a diverse, shifting group of societies that met within different colleges at Oxford during the early 1730s.6 The title “Methodist” was originally an aspersion, cast by fellow students who satirized the methodical, monotonous religious life that its members promoted.7 John Wesley was particularly taken with rules for keeping one’s life in the narrow way, as his mother, Susanna, had imposed a sense of spiritual order at an early age. He read widely and was particularly taken with Dr. George Cheyne’s teachings on health and nutrition, as well as seventeenth-century devotional writer Jeremy Taylor’s rules for holy living.8 These rules included limiting entertaining diversions and mixing with the opposite sex in order to keep the mind focused on spiritual goals. The Holy Club meetings elaborated on the methodical practices of regular prayer and selfexamination that John Wesley had begun to institute in his personal practice. These proto-Methodist meetings included a mix of discussions of classical literature and theology, alongside the dissection of a holy life.

If we take the Holy Club as the opening chapter of Methodism, a few aspects central to the Methodist character become apparent. The Holy Club established some of the key elements in Methodist religiosity, the spiritual fellowship and sociability found outside of formal institutions. The Holy Club correlated religious goals with social ones; members held each other accountable for maintaining daily religious practices, but also for refraining from social practices that could be harmful to their souls. The club advocated getting out of bed when it was still dark and praying very early, so as to avoid masturbation.9 The club also warned against running after the “pretty creatures” of London. Charles Wesley frequently attended London theaters and had some romantic relationships with actresses there.10 When criticized by his older brother John, Charles responded, “What, would you have me be a saint all at once?”11 Also, these proto-Methodists invoked a strong sense of association, formulating a network that went outside of blood family ties. One of the crucial aspects of family ties is religious association, and families expected that their children would grow up in the religious traditions of their family. In formulating their own religious society, the Wesley brothers provided a forum for religiosity that was distinct from their fellow students’ religious practices of churchgoing. The Holy Club’s underpinning belief was that institutional adherence was not enough. On the individual level, pulling away from traditional religious institutions had an effect on the individual’s family; taken collectively, the innovation of new spiritual organizations was a form of dissent.

Religious dissent was not welcome in eighteenth-century English society. Yet Oxford, like many English institutions, was growing more tolerant of dissent in the early eighteenth century. The fact that Oxford University tolerated Holy Club meetings in the early 1730s demonstrates that the eighteenth-century Church of England was, to a degree, more lenient toward dissenters than it had been in the previous century. In fact, this toleration contrasted sharply with the violently fractured religious atmosphere of the seventeenth century, which witnessed the English Civil War. Dee Andrews writes that in the eighteenth century, “Nonconformists were no longer perceived by the Anglican majority as dangerous schismatics separated from the one true church, but as Christians called by a particular name in legal distinction from the established church. English religion, that is, was denominationalized.”12 Linda Colley similarly argues that while religious dissension generated hostility and violence during the English Civil War period, the eighteenth century was a time of cool disregard toward religious dissent. This shift in religious tolerance was significant. In the previous century, religious dissent had been viewed as a political and social scourge, but for most of the eighteenth century, dissension was reduced to a mere legal stigma. Adherence to the Church of England was still a requirement for public office, but the Toleration Act of 1689 had taken the sting out of dissenting. Colley maintains that, in practice, Protestant dissenters faced no discrimination, and religious discord centered on emotional and political opposition to Catholicism, rather than internal Protestant divisions. Britons, as Colley argues, became unified as Protestants against internal and external enemies; exactly which brand of Protestantism one espoused mattered less than ever before.13

American attitudes toward religious dissent were shifting by the eighteenth century as well. The Puritan hegemony of the North and the strictly Anglican culture of the South gave way to a deeply pluralist religious culture that had taken root in the colonial period.14 During the late 1730s, the Great Awakening, which began with small revivals in New England, opened the way for the establishment of multiple churches. Additionally, fresh immigrants brought new religious institutions with them, especially in the form of Lutheran and Presbyterian churches in the mid-Atlantic colonies of Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York. This was a period of rapid institution building, and churches of many different denominations began to spring up on the American landscape.15

While official church and governmental policies were demonstrating some tolerance of Protestant dissent by the early eighteenth century, wider social acceptance of dissent was slower to emerge. In America and England, Methodists faced violence on the streets and repudiation in the press. Even though laws against dissenters were not enforced in the penal codes, dissenters were still barred from universities and civic offices. There were fewer legal penalties, but social penalties remained in the eighteenth century. Many Methodist preachers experienced the violence of mobs on their preaching circuits. Wives incurred their husbands’ wrath when they joined with evangelical groups, and children felt their parents’ displeasure after attending meetings. Pamphlets warned that Methodists were political and social scourges equal to the dissenters of the seventeenth century, even Catholics in disguise.16 The eighteenth-century Methodist experience in England complicates Colley’s assertion that hatred of dissenters dissolved in the face of anti-Jacobite fears, or that society drew a stark division between Catholicism and dissenting Protestantism. The early Methodist story points to the fact that eighteenth-century English religious culture was still an inhospitable place for dissenting religious groups to grow.

Throughout the eighteenth century, leaders within the Church of England feared nonconformist sects that threatened to woo believers away. Dissent worked both inside and outside the Church of England. Though the church claimed that 90 percent of English people were members, their formal allegiance masked the fact that many English were no longer centrally involved with the Anglican Church. There were many people who called themselves Anglicans, while attending dissenting group meetings. The Church of England had lost numbers to the dissenting splinters of radical Protestantism, such as the Quakers and Baptists in England. As the eighteenth century progressed, the Anglican Church had a sense of withering, while nonconformist sects bloomed. Similarly, prior to 1740 in America, the Church of England was growing through its establishment of new churches and expansion of membership, particularly in Virginia. Yet during this same period, there was a sense of formal membership without much fervor.17

Faced with this sense of growing disaffection, Anglicans embarked on a missionary course. In the beginning of the eighteenth century, Anglican leaders became more active in recruiting and retaining their members. Though the Church of England had formerly repudiated itinerant preaching, it embraced the itinerancy of ordained ministers for the purpose of mission work in the eighteenth century. The Society for the Propagation of the Gospel in Foreign Parts (SPG) and the Society for the Propagation of Christian Knowledge (SPCK) formed as missionary branches of the Church of England. These groups were working in both England and America, seeing the home mission as important as the mission to convert the apathetic English populations in America.18 Thomas Bray, the Anglican commissary for Maryland, founded the SPCK for colonial work in 1698. The SPG was specifically founded for missionary work abroad in 1701. In the same vein, thirty to forty reforming societies sprang up in London by the 1730s. They converted the unchurched and unbelieving in England and promoted the idea that the Anglican Church was fulfilling a primitive Christian mission by forming these societies.19

The Anglican missionary impulse was part of a larger wave of what David Hempton calls “a more benign religious version of the infamous triangular trade of slavery and cotton that fueled the economies of empire.” As Hempton’s work on transatlantic Methodism confirms, evangelical pietists, and particularly Moravians, fed an unprecedented wave of mobility. The movement included not just people, but also a print culture that spread its influence from areas in central Europe through western Europe and the broader Atlantic world. Hempton writes, “As the expansion of Europe into the New World gathered pace in the eighteenth century, the spoils would go to those who were prepared to be mobile, and who had a powerful religious message to trade.”20 John and Charles Wesley volunteered to be part of the SPG mission to America, to retain the English souls of the colony and convert the Native American ones. The SPG was especially keen to remedy the underrepresentation of Anglican ministers in the less populated areas of America, particularly the American South where Anglo-American colonists needed ministerial attention.21

Methodist Beginnings in America

As John and Charles Wesley headed for Georgia during the winter of 1735, they found themselves in a motley, multinational shipboard community. John Wesley immediately began learning German in order to converse with the largest group of immigrants on board, a band of twenty-six Moravians, and he attended their evening services. Wesley wrote in his journals that he and his associates quickly reestablished their regularly scheduled ways once on board. They instituted daily public prayers and preaching to some of the eighty English-speaking passengers, alongside a few Moravians. The Anglicans and Moravians established regular Sunday services, and John Wesley noted that he administered communion to “[a] little flock” of half a dozen people, which included some unconverted shipmates. The Wesleys even set a schedule for catechizing and exhorting their fellow passengers. This evangelical pattern fit easily into the shipboard context where the diverse, captive audience would have provided a ripe opportunity for the Anglicans to try out their evangelizing methods.22

The trip to America was an important formative chapter in Methodism because this transatlantic journey prompted John Wesley to realize that he had not experienced a full conversion. The vulnerability of this realization, coupled with his exposure to Moravianism, made him ripe for incorporating Moravian ideas into the bedrock of Methodist practice. In the violent Atlantic storms, he confronted the shameful realization that he feared death, which revealed the unprepared state of his soul. During one particularly harrowing storm, he noticed his Moravian shipmates were wholly at peace. “In the midst of the psalm wherewith their service began the sea broke over, split the mainsail in pieces, covered the ship, and poured in between the decks, as if the great deep had already swallowed us up. A terrible screaming began among the English. The Germans calmly sung on. I asked one of them afterwards, ‘Was you not afraid?’ He answered, ‘I thank God, no.’ I asked, ‘But were not your women and children afraid?’ He replied mildly, ‘No: our women and children are not afraid to die.’”23 The Moravians’ stalwart faith and pietistic spirituality appealed to Wesley, and they became an important inspiration for Methodist spirituality and organization. Moravians possessed something else that Wesley envied—a sense of belonging, a real sense of religious family.24

In February 1736, after almost three months of rough sea travel, the ship made it to Georgia. Once on dry land, John Wesley was able to further observe the Moravian community in action when he set up his first temporary residence with the Moravians. In his journal, Wesley described the group’s daily devotion to God and his surprise at their steadfastness and peacefulness. He continued to have regular contact with the Moravians, and considered them to be his spiritual family, even after setting up an independent house as a minister. Soon after landing, John Wesley met August Spangenberg, a well-educated and devout Moravian, who was the founder of American Moravianism. After talking with Spangenberg, he realized that his trials at sea had not been enough to prompt a real conversion, but merely an awakening to his sinfulness. When Spangenberg asked if Wesley had a personal feeling of salvation, Wesley realized he was unsure how thoroughly he believed he had this assurance.25 He sought this sensibility of God’s forgiveness of sins, which many Moravians possessed. Following his experience with American Moravians, Wesley also began a lifelong study of the works of German pietistic theology.26

As impressed as Wesley was with the Moravian community, the religiosity among Georgia’s English population disappointed him. During his mission in Savannah, John Wesley discovered some of the difficulties of establishing regular religious worship in the colonies. The colonial leadership made it clear that his first duty was to the English settlers and that preaching to Native Americans took him too far away from his English flock. He admitted that organizing religious worship for white people in Georgia alone was a steep task, stating, “Even this work [Savannah’s parish] is indeed too great for me.”27

In Wesley’s summary of the failures and successes of the Georgia mission, he counted spreading the gospel to “African and American Heathen” as one of his successes.28 In reality, his mission to Native Americans was by every measure unsuccessful, but the goals of mission work had an important effect on Wesley’s activities in Georgia. With the aim of converting Native Americans in mind, he developed his method of evangelizing, a process he would calibrate for many years. In addition, the goals of his mission established that the Methodist ideal was to have an inclusive fellowship of different peoples in the same religious family. Not evangelizing Native Americans was a missed opportunity, according to Wesley, who wrote that Indians were the ideal converts, like “little children, humble, willing to learn, and eager to do the will of God.”29 Wesley confirmed a common misperception of Native Americans, that they were open, passive, and ready to be religiously inscribed.30 Closer to the end of his time in Georgia, he wrote in September of 1737 that his mission among Native Americas was pretty hopeless. There was “no possibility of instructing the Indians; neither had I as yet found or heard of any Indians on the continent of America who had the least desire of being instructed.”31 He had a little more success with meeting and having spiritual conversations with some African Americans. He had planned to travel to different plantations in order to reach slaves, after he identified the planters who would allow him to preach.32 Yet, there is no evidence in his journal of any sustained contact with African Americans. Moravians likewise sought to establish a mission that included the conversion of non-Christians and crossed racial boundaries. Though Moravians also ultimately failed in their Georgia mission, they succeeded in expanding their community and fellowship to African Americans in the West Indies and in North Carolina during the eighteenth century.33

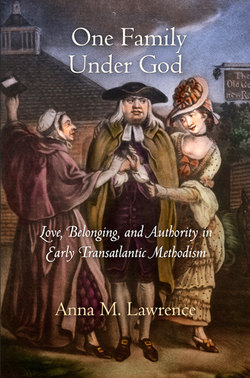

Figure 1. Wesley Conversing with a Young Negress, artist unknown, ca. 1890. Courtesy of the Drew University Methodist Collection.

If John Wesley did not succeed in fulfilling his desire to convert Indians and African Americans in America, he did succeed in other ways; his American mission established the foundation of Methodist practices, such as individual assurance of faith, lay preaching and participation, hymn singing, and extemporaneous prayer.34 The primary goal of Methodist spirituality became a personal experience of the promise of salvation, the assurance that he witnessed among the Moravians in America. Wesley also began to establish some of the touchstones of Methodist practice, especially the matrix of domestic meetings that would later become the basis for class and band meetings. Classes and bands were groups of Methodists who gathered in members’ homes for the purpose of buttressing their spiritual commitment. Wesley’s early Methodist organizations laid out a kind of compromise between church adherence and dissent. He advocated being a member of the Church of England, while attending extra-institutional meetings.35

While Wesley fairly strictly followed the Anglican Common Book of Prayer in Savannah, he was conducting meetings in individual homes as well by April of 1736. Wesley wrote about the purpose of these first religious meetings in Savannah: “(1) to advise the more serious among them to form themselves into a sort of little society, and to meet once or twice a week in order to reprove, instruct and exhort one another. (2) To select out of these a smaller number for a more intimate union with each other, which might be forwarded, partly by our conversing singly with each, and partly by inviting them all together to our house.”36

This duality of early Methodists was fairly common throughout the first decades of the group’s existence. Many held official membership in a standing church, but Methodism offered them the community of a spiritually dedicated fellowship. Like John Wesley himself, many were officially members of the Church of England and depended upon the Anglican Church for the rites of communion, along with the conferrals of baptism and marriage. The vast majority of eighteenth-century Methodist preachers were not ordained, but if they were ordained in the first decades of the group’s existence, they were ordained in the Church of England. Thus, the Church of England offered a level of respectability and the necessary rites of sacraments, but Methodism offered something outside of those formal requirements.

What Methodism offered was an intimate union with other like-minded Christians. The idea of reinforcing religious practice through a social form, such as band and class meetings, defined Methodism and early evangelicalism, more generally. By designating bands as a central feature, Wesley wrote in A Short History of the People Called Methodists that this was a formative chapter in instituting bands and class meetings.37 The “band” was a small group of Methodists, segregated by sex, and members were encouraged to provide mutual support and criticism. The band was a forum for complete openness and intimacy; in the band meeting, “we should come as close as possible, that we should cut to the quick and search your heart to the bottom.”38 These meetings were significant in establishing later Methodist practice, formulating the voluntary, lay-driven nature of Methodism, and particularly stressing the importance of forming a spiritually supportive, elective family.

Organized Women

Women were at the center of this nascent Methodist practice in colonial Georgia, becoming active as laity and as leaders. John Wesley appointed at least three female lay leaders in Georgia: Margaret Burnside, Mrs. Robert Gilbert, and Mary Vanderplank.39 Yet, the impetus for Wesley’s formation of the band structure and supporting female authority was planted well before his mission in America.

As a child, Wesley witnessed household religious meetings, and in these meetings he also observed his mother, Susanna Wesley, exercising domestic religious power. When her husband, Samuel Wesley Sr., was absent from the house on extended business, Susanna Wesley pulled her children together for religious meetings, consisting of prayers and reading sermons. When members of their parish began to attend as well and she preached to them, Samuel objected, saying it was improper for a woman to lead a congregation.40 Susanna defended her right to lead them, arguing that, “as I am a woman, so I am also mistress of a large family. And though the superior charge of the souls contained in it lies upon you, as head of the family, and as their minister yet in your absence I cannot but look upon every soul you leave under my care as a talent committed to me, under a trust, by the great Lord of all the families of heaven and earth.”41 Susanna Wesley drew the ideas of home meetings from the missionary pamphlet Propagation of the Gospel in the East.42 She saw herself as head evangelical of her family and thus instituted weekly meetings with her children to interview them about their spiritual well-being.43 There is no doubt that John and Charles Wesley absorbed this strong, elemental example of women’s religious authority being rooted in the family, particularly as they began to formulate social groups at the basis of Methodist practice. It is particularly striking that Susanna Wesley’s basis for authority combined the religious inspiration of mission work with the mother’s duties in the household. Through her example, this concept of evangelizing through the household was planted in Wesley’s mind well before his time in Georgia. In addition, Welsh revivalists had been meeting in select groups by the mid-1730s, and Wesley would have been aware of this practice.44

The American experience sparked the creation of Methodist bands in that Wesley consciously synthesized these precedents and the religious structures of the Georgia Moravian community. In organizing the Anglican community of Georgia, John Wesley drew specifically from Moravian models, which had single-sex groups. The Methodist band was almost certainly inspired by the Moravian organization of “choirs.” The Moravian family order was based in these choirs, which divided members according to sex, marital status, and age. In this sex segregation, Moravian women had considerable power overseeing other women.45 Moravian women held various leadership offices: nurse, deaconess, eldress, and chief eldress. Wesley followed this innovation of appointing female leaders, which abraded local colonial sensibilities. The colonists complained that Wesley appointed “Deaconesses, with sundry other Innovations, which he called Apostolick Constitutions.”46

Wesley’s proto-Methodist family model was based on the Moravians, but there were also significant differences between the family order that Methodists adapted and the Moravian model. In contrast to Methodists, Moravians lived in self-contained societies and shaped their communities around their religious order.47 The Moravian choir system became the basis for community organization in their settlements throughout the Atlantic Moravian world, starting in the late 1730s.48 In 1741, American Moravians formed their largest community in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania, where choirs, not individual families, were the basic unit of social, religious, and economic organization.49 The community lived in sex-segregated units, divided into groups designated as “Single Brethren,” “Single Sisters,” and “Married People.”50 The reasons for this segregation were practical and spiritual. All of the members slept, ate, worshipped, and worked within these units. By keeping individual members oriented toward the community and curtailing any inclination to pair off into couples or separate from the community into distinct nuclear families, Moravians kept individuals focused on their religious goals. As with other designed religious communities, the devolution of individual families contributed to the evolution of a higher religious family.

The Moravian model radically limited the influence of particular families, assigning child rearing to the larger community. Even before children were born, they were assimilated into the larger religious structures. Moravian leader Nikolaus Ludwig von Zinzendorf wrote, “When the marriage has been consecrated to the Lord and the mother lives in continuous interaction with the Saviour, one may expect that already in the mother’s womb the children form a choir, that is, a grouping of the community consecrated to the Lord’s work.”51 The community assumed responsibility for children at their weaning, when communal supervisors took charge of raising the children’s choir. Parental authority was curtailed in this system, deferring to the broader group authority. Moravian marital and sexual practices diverged from those in mainstream Protestant groups. Matrimony was not solely an individual or family concern, but a decision in which the community had the primary stake and interest.52 Historian Aaron Fogleman’s work confirms that even the act of conjugal sex was part of Moravian religious teachings, making marital sex a holy and radically guilt-free activity. Moravians saw marriage and sexual acts as healthy contributions to their religious community.53

Methodists never separated themselves from society and never instituted any sort of community order as the Moravians did, but they shared some of the same ideals and practices regarding the religious family, social religious goals, and divine authority. Like the Moravian choir, the Methodist band was a place for intense spiritual sharing and growth. Both Methodists and Moravians presumed that the greatest growth would occur among like-minded individuals, who were at the same stage in their life and could support each other. After Wesley returned to Europe following his Georgia mission, he continued to draw from Moravian ideas, talked extensively with Moravian leaders, and even stayed in their community in Herrnhut. Even though Methodists and Moravians would eventually part ways, the two religious groups shared a common genetic component following this contact in America.

The Moravians also affected John Wesley on a personal level. As the Moravians in Georgia promoted the religious benefits of sex and family formation, Wesley also began to think about his own marital possibilities. At the start of Wesley’s mission in Georgia, he was thirty-two, overripe for forming a romantic attachment. Propriety called for him to be married in order to claim respectability as a religious leader and as an upper-middleclass man. In 1736, John Wesley started a relationship with a younger woman in the Savannah congregation, Sophy Hopkey. Wesley and Hopkey visited various congregations around Georgia together, evangelizing together and planning a future together. However, as Wesley’s own account confirms, he was ambivalent about his intentions toward Hopkey and about marriage in general.54 He wrote that she was his soul mate and that they shared a physical and spiritual bond, but he also wrote that he was not sure he would ever marry.55 When Hopkey accepted a proposal of marriage from another man, Wesley was hurt and confused.56

This failed relationship would have been a simple romantic misstep (and not Wesley’s last one), but what unfolded after the dissolution of their relationship became much more complex, implicating the Anglican mission in Georgia and Wesley’s career. Wesley proceeded to exclude Hopkey from communion on the grounds that her marriage had been improperly publicized.57 Once he attempted this revenge, her family got involved and had Wesley arrested on charges of defaming Hopkey and failing to give her communion. He was also tried for “ecclesiastical innovations” and for being a “Jesuit, a spiritual Tyrant, a Mover of Sedition.”58 The essential maneuver that got Wesley in trouble was his legalism regarding Hopkey’s apparently improper marriage. While the core of his mission in Georgia was to “regularize” the colonists’ religious practices and sacraments, including marriage, baptisms, and communion, his stance on Hopkey’s improper marriage seemed personally motivated.59 In December of 1737, as authorities were moving to prosecute him on further related charges, he escaped to Charleston and then sailed to England.60

Wesley’s hasty retreat from Georgia and the mission’s altogether ignoble conclusion embarrassed not only Wesley but also subsequent historians of Methodism. Wesley first published his journal in order to quell the controversy that arose from his rumored unscrupulous behavior in Georgia. Historians have struggled to explain why this successful evangelical organizer was so ineffective at either evangelizing or organizing in this first attempt. Many biographers have framed this rocky period, as well as other episodes in the romantic lives of John and Charles Wesley, with a familiar narrative of good men who were unwittingly snared by besotted women. Methodist historian Frank Baker suggests that the Wesley brothers were bound to find trouble in the Georgia colony, due to their bachelor status and their personal charms. Baker writes, “Both brothers suffered from the fact that they were earnest and eligible bachelors, becoming focal points for dissimulation, jealousy, intrigue, and gossip.”61 Henry Rack confirms this sentiment in the title and content of his chapter on the Georgia mission, “Serpents in Eden.” This title refers primarily to three women in Georgia, Sophy Hopkey, Beata Hawkins, and Anne Welch, though Hopkey is singled out as “the worst of all the serpents in [John Wesley’s] Eden.”62 The other “serpents,” Hawkins and Welch, had reportedly caused Charles Wesley’s early departure from the colony. According to Charles Wesley, Hawkins and Welch led him to believe that they had had adulterous affairs with Georgia’s founder James Oglethorpe. When he tried to confront Oglethorpe about the accusations, the women reputedly recanted their initial accusations and made Charles Wesley the offender instead. Regarding these difficulties in Georgia, Rack concludes: “The whole episode suggests murky undercurrents of sexual jealousy and hysteria of which these idealistic and inexperienced clergymen were more or less innocent victims.”63 Wesley biographers have described the “pack of angry women”64 in Georgia as “scheming,” “petty,” and “malicious,” in order to dismiss the women’s accusations against John and Charles Wesley in this period.

In some ways, historians have simply reflected the ambiguity that John Wesley, in particular, felt about marriage. Both Charles and John Wesley were at critical junctures in their lives, on the precipice of starting a new religious movement, and also considering whether they needed to be married or single to be effective religious leaders. In his parting words to Charles Wesley, Oglethorpe told him that he believed Wesley needed to marry to save himself future trouble, and he also thought marriage suited Charles Wesley and his spiritual mission. “On many accounts I should recommend to you marriage, rather than celibacy. You are of a social temper, and would find in a married state the difficulties of working out your salvation exceedingly lessened and your helps as much increased.”65 In contrast to his brother, John Wesley did not possess the same “social temper.” A proper marriage would legitimize his social standing and his leadership of a religious group, but he was still uncertain. John Wesley was ambivalent about how central women were to his personal mission, even as they were increasingly important to the broader Methodist family.

In sum, the Wesley brothers were seemingly naive about the need to respect certain colonial power structures and inflamed the wrong people.66 While the English colonists were jealously establishing favor with Oglethorpe and monitoring divisions of land parcels, some saw religion as superfluous, or worse, an obstruction to the colonists’ economic success.67 Overall, the Wesley brothers’ rigid social and religious expectations made them ill-suited to the Georgia mission. The colonists accused John Wesley of being such a stickler for proper ceremony, titles, membership, and sacraments, which seemed so inappropriate in this hardscrabble colony, that they took him to be a Catholic in disguise.68

Yet America continued to influence Wesley long after he left Savannah. The most immediate effect of his Georgia mission and its disastrous final chapters was that it drove him to publish his first journals. In order to defend his excommunication of Sophy Hopkey, Wesley was compelled to print an account that emphasized the righteousness of his holy mission.69 Long-lasting effects included Wesley’s foundation of the social structure of Methodism, women’s centrality to this structure, and Methodist attention to the ideals of missionary work.

Revivals in England and America

Despite the significance of the American mission to John Wesley’s formulation of Methodist practice and thought, he left behind no sustainable Methodist organization in America. Methodist historians have tended to view American Methodism as taking root in 1766, when Wesleyan Methodist immigrants formed a significant, if small, society in New York.70 Yet from 1738 to 1766, Methodism did exist in America, though it was mainly unattached to Wesleyan Methodism and under the leadership of George Whitefield. Whitefield, an ordained Anglican minister and fellow Holy Club member, picked up where Wesley left off his mission in Georgia. Whitefield arrived in Savannah on May 7, 1738, with some desire to cultivate the nascent Methodist organization there, but he observed “many divisions amongst the inhabitants.”71 The evangelical seeds had scattered, and it was difficult to see much obvious flowering left behind by the Wesleyan mission.72

Whitefield made successive preaching tours in America, attracting large crowds during his wildly popular tour of America in 1739. He preached to large interdenominational crowds everywhere he went, and he was widely known throughout America, England, and Wales.73 His emotional, charismatic style of preaching was not altogether new to the colonies at this point. Whitefield followed in the footsteps of American revivalists like Jonathan Edwards and Gilbert Tennent, who were even more emphatic about Judgment, hell, and damnation than Whitefield.74 And like Edwards and Tennent, Whitefield’s theological underpinning was primarily Calvinist, emphasizing the unchangeable election of the saints and the burden of original sin.75 Whitefield was a truly transatlantic itinerant, gathering large crowds on both sides of the Atlantic. In 1742, he reveled in the level of revivalism he had seen in England, Scotland, Wales, and New England, and he rhapsodized, “I believe there is such a work begun, as neither we nor our fathers have heard of. The beginnings are amazing; how unspeakably glorious will the end be!”76

Like Wesley, Whitefield had a sense of being a missionary in the colonial American arena, and he, likewise, saw it as part of his mission to work at converting African Americans. However, while evangelical preachers paid more explicit attention to converting slaves, some scholars argue that Calvinist theology naturally inhibited slave conversion through its emphasis on the predestined elite.77 The Church of England saw its missionary efforts through the SPG and the church’s colonial establishment as working toward a “Humane and Christian system of slavery,” which would do nothing to challenge slavery. Instead, Anglican pastors saw their mission as improving slaves’ commitment to obedience and hard work through their sense of religious duty.78 Whitefield, though critical of the SPG and the Anglican Church, operated within this sense of Anglican mission while in America. While Whitefield converted slaves, he directly promoted slavery by supporting the establishment of slavery in Georgia and by becoming a slave owner in the 1750s.79

Figure 2. Enthusiasm Display’d, or The Moor-Fields Congregation (London: C. Corbett, 1739). George Whitefield is standing on two women; one has a mask and is named “Hypocrisy,” and the other Janus-faced woman is “Deceit.” Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

While Whitefield and Wesley had both approached America with a sense of mission, their methods and their theological message were quite different. Whitefield’s emphasis on the theology of predestination had caused some friction with Wesley. Contrasting with Whitefield’s Calvinist views, Wesley espoused an Arminian emphasis on the potential for universal salvation or “free grace.” As well, Wesleyan Methodists distinguished themselves from their Calvinist counterparts by searching ceaselessly for entire sanctification, a true assurance that one had reached a perfect, sinless state. In 1740, Wesley gave a sermon in Bristol where he declared that Calvinism implied that God abandoned people and incited the nonelect to antinomianism.80 Unlike Wesley, Whitefield separated from the Anglican Church, openly criticizing its efficacy in America. He further charged that Anglican missionaries were “corrupt in their principles and immoral in their practices.”81 After his death in 1770, Whitefield’s followers were folded into what became the predominant strain of American Methodism, Wesleyan Methodism. Despite theological differences, Wesley and Whitefield remained friends; the Wesleys and George Whitefield considered themselves a “threefold cord,” working toward the same goal.82 As perhaps a final testament to their friendship, Whitefield had designated Wesley to conduct his funeral.

Even while distinguishing his own movement from Whitefield’s, John Wesley kept a close eye on the spread of American revivalism.83 Wesley had read Jonathan Edwards’s collection of New England conversion accounts, A Faithful Narrative of the Surprising Work of God, in the Conversion of Many Hundred Souls in Northampton, and Wesley was deeply affected by this collection. He drew parallels between American conversion experiences and those in his own circle.84 Wesley not only admired Edwards’s book, he reprinted it in London in the 1740s and 1750s.85 As Wesley saw the connections between the experiences of converts in America and England, he began to conceive the scope of his mission as transatlantic, even worldwide. Surveying the numerous reports of large revivals in the 1740s, Wesley wrote, “Many sinners are saved from their sins at this day, in London … in many other parts of England; in Wales, in Ireland, in Scotland; upon the continent of Europe; in Asia and in America. This I term a great work of God; so great as I have not read of for several ages.”86

Throughout the transatlantic world, the publication of conversion narratives exploded during the mid-eighteenth century. Sharing conversion experiences was an important way for evangelicals to connect to one another. Publishing conversion narratives served various functions, asserting both the universality of this experience and the common components evangelicals found in their journeys toward salvation. Conversion narratives provided Methodists and other evangelicals with the sense that their experiences were unique but not singular. This transatlantic network of writing created a spiritual community that crossed denominational and national boundaries.87

By the late 1730s, Wesley began to conceive of a religious community centered on the conversion experience, social discipline, and spiritual fellowship. In 1738, Wesley established the Fetter Lane Society in London; this society was cooperatively run with the Moravians. The society attracted converts, organized them into bands, and laid out the rules for social and religious discipline. Fetter Lane established the possibility of merging Moravians and Methodists in England, but, by 1740, John and Charles Wesley rejected this idea. The more radical elements of Moravian communalism and sexuality were problematic to the Wesleys.88 But even more troubling was the theological divide between Methodists and Moravians. The Wesleys contended that the Moravians had antinomian tendencies, while Moravian leader Count Zinzendorf was bothered by John Wesley’s insistence that it was possible to achieve Christian perfectionism, a state where one could no longer sin.89 Moravians were also troubled by the enthusiasm central to Methodist conversion experiences: the noisy groaning, crying, and physical fits. Though Wesley had initially been somewhat skeptical of enthusiasm, by 1739 he had become convinced that enthusiasm was a true expression of the Spirit of God in the believer. Wesley had concluded this from seeing the similarities in physical responses to conversion, found in both Jonathan Edwards’s conversion accounts in America and those he witnessed in England. He reasoned that these remarkable similarities meant the responses were legitimate.90 Moravians countered that stillness was the appropriate response to conversion and that conversion was instantaneous, while Wesley thought this was not the only valid manifestation of conversion.91 With the additional and distinct step of sanctification, which offered to converts a final stage of sinless perfection, Methodists saw conversion as a longer process than that of the Moravians. The theological rift was evident in their different social plans as well. Wesley sought an evangelical society that was open to all, in contrast to the sort of bounded community that was necessary to reach Moravian goals.92

In 1739, following Whitefield’s lead, John Wesley began to preach in open air settings and established himself as an itinerant preacher.93 Wesley had a sense of mission now and would not be a traditional Anglican minister, whose scope was bounded by a single parish. He wrote, “I have now no parish of my own, nor probably ever shall.… I look upon all the world as my parish”94 He began to establish a group of itinerant preachers that would become a spiritual brotherhood. They would share poor pay, poorer conditions, and even mob violence to follow their sense of spiritual calling. Officially starting in 1744, Wesley began to organize a few ministers and a rapidly expanding group of lay preachers.95 Itinerant preachers were predominantly lay preachers who had little formal training. But they were by no means without regulation. Wesley held control over their activities, prohibiting their administration of sacraments, and ordering itinerants into rotating circuits, ones he reassigned regularly. Preachers were expected to cover a large area, never staying in one community for very long; they coordinated and supervised the ongoing spiritual development of a set of communities. The basic structures of the laity, the classes and bands, were the local forms of Methodist organization. The preacher was the connection between these societies and the leadership, consisting of John Wesley and, eventually, the Conference of Preachers.96

Wesley established an explicitly paternal system from the beginning.97 He maintained control of many of the decisions on both the organizational level (preachers’ circuits) and the personal level (marital choices). In 1766, at a conference in Leeds, he defended his power over Methodists by stating that Methodist followers asked for this sort of leadership. He stated that prospective preachers aspired to “serve me as sons and to labour when and where I should direct.” In Wesley’s self-defense of his centralized power, he maintained that his control was not tyrannical in that evangelicals willingly submitted themselves to it. He argued, “the Preachers have engaged themselves to submit … to serve me as sons in the gospel.”98 Wesley argued that the basis for his authority was voluntary, while the terms were compulsory and nonnegotiable, like the bonds of a natural family.

While Wesley’s control seemed absolute in some realms, he also established important sources of power within the laity. In England and America, early Methodist societies included significant lay leadership and a considerable number of women. In Bristol, which was the center of Wesley’s revivals, women were the predominant lay leaders. In 1742, in the London Foundery Society, women leaders outnumbered men by fortyseven to nineteen.99 In the first decades of Wesleyan Methodism in America, women were likewise the largest group, outnumbering men by three to two in some areas.100

As Methodism became more established, bands and classes became the primary units of lay organization. As discussed above, bands were sites of close spiritual fellowship, based on the early models of the Holy Club and the first meetings in Georgia. Bands were usually single sex and formed of like-minded people from similar backgrounds and shared marital status, much like the Moravian organizations. The bands were supposed to foster intimacy, providing a comfortable space for sharing confessions of sins and self-searching.101 The American Methodist superintendent Francis Asbury described bands as “little families of love.”102

The classes, on the other hand, were the basic unit of official Methodist membership. Depending upon the area, they could be mixed sex or single sex. When an area was newly organized, the class might include all the Methodists from a particular community, and when the membership grew, the classes would become subdivided by different characteristics such as marital status, sex, and race. They were generally larger than bands, composed of usually a dozen members, and part of the economic undergirding of Methodism.103 In class meetings, Methodists would relate conversion narratives and receive instructions on Methodist social interactions. Classes would be instructed on the rules outlined in the official guidebook for Methodist social behavior, the Methodist Discipline, including correct behavior, avoiding profanity, refraining from excessive conversation and conduct, and plain dressing.104 To become a member of a class meeting, one had to be deemed fit for this select circle. This fitness was symbolized by the granting of a class ticket, which was a piece of paper that stated one’s name and location. Proving one’s mettle this way sometimes took months of regular attendance at preaching, prayer meetings, and interviews. Preachers and experienced Methodists were the judge and jury as to a new Methodist’s real intentions or seriousness. Many eighteenth-century Methodists describe the moment of acquiring their membership ticket as an essential step in their road to a rarefied spirituality.105 Getting this ticket, this symbol and certificate of acceptance, meant joining a specific Methodist family that would include mentors and guides (brothers, sisters, fathers, and mothers) throughout each dedicated Methodist’s life. Class meetings defined the basis for membership within this family, who was inside and outside this group. When Francis Asbury arrived in America in 1771, one of the first things he did was to be sure that the class meetings were made up of qualified Methodists and that outsiders were not allowed to meet with them.106

The bands, class meetings, and circuits were extra-institutional structures of Methodism that established its character as a social movement from the beginning. The people of Methodism were the basis for its organization. While many Methodists, especially those in England, might be nominal members of the Church of England and attend services regularly, Methodist social structures provided the backbone for their religious association outside of more traditional brick-and-mortar sites for worship. Aside from the central motivation for spiritual growth, the goals of the Methodist structures were social ones: discipline, identification, association, and fellowship.

While Wesleyan Methodism did not officially take root in America until the end of the Great Awakening, this wave of revivalism paved the way for the Methodist movement to come. Evangelical Baptists, Lutherans, Congregationalists, Presbyterians, and Moravians all had a hand in establishing the predominant evangelical message of new birth. In particular, Baptists paved an important path for Methodists in the South, where they used some similar elements of emphasizing emotional preaching styles and the centrality of rebirth.107 Despite this wave of evangelical growth in America, Wesley waited a while to include America in his missionary plan.108 In essence, Whitefield was the primary evangelizer and Methodist leader, underlining the Calvinist flavor of the First Great Awakening. Until the late 1760s, he seemed content to allow lay Methodists to drive the American Methodist movement. In the 1760s and 1770s, some Wesleyan Methodists began immigrating to America, and this seems to have prompted Wesley to advance his mission there.109

In the 1760s and 1770s, Wesleyan Methodism found areas of expansion, like the Delmarva Peninsula, where there were great numbers of English settlers and where the Church of England was established but not thriving.110 The most significant growth took place in Maryland, Delaware, New York, and Philadelphia, where many Irish Anglican immigrants settled. David Hempton argues that these regions were ripe for evangelizing because “Methodism offered a more enthusiastic religion for Anglicans in an environment unsuitable to liturgical and moralistic refinement.”111 Methodists thrived in areas with strong Anglican Church establishment, because many Methodists were dependent upon and connected to the Church of England as their home institution. Methodists were routinely baptized in and often official members of the Church of England. They often attended their locally established churches, but met with Methodists outside those services. The Church of England offered sacraments and legitimacy to many English and American Methodists, especially prior to the 1780s. Methodism offered believers more than a sacramental home; it gave them a fellowship and way of life. Early Methodists felt strongly that real fellowship was essential to converting one’s soul and to staying on the right religious path.

Certainly, Wesleyan convert Barbara Heck, an emigrant from Ireland, felt that a Methodist community needed to be established in New York to keep evangelical converts on the right path. In 1766, Heck helped light the Wesleyan Methodist fires in America. Heck and other immigrants, who had been converted during Wesley’s Irish campaign, settled in New York City. One night in the fall of 1766, Heck interrupted a card game in another immigrant’s home by seizing the cards off the table and throwing them into the fireplace. Heck was symbolically renewing vows to keep to the Methodist rules of avoiding trivial diversions and pointing out the fate of their souls if they kept at this; their souls would burn in hell, like so many cards in the fire. She also reportedly urged Philip Embury, a fellow Irish immigrant, to begin itinerating in New York.112 Heck and Embury formed singlesex classes in New York City in 1766, and soon after there was a “modest Methodist community” in Philadelphia as well.113

The New York society was important in cultivating an early Methodist organizer and preacher, Thomas Webb. Captain Webb had fought in the Seven Years’ War, converted to Methodism in England, and was very close to John Wesley, who encouraged his enthusiasm. He began preaching in various New York meeting spaces and organized a Methodist class in Brooklyn that balanced a mixed black and white membership. Heck, Webb, Embury, and other newly immigrated English Methodists built the first meetinghouse in New York City, and this was done largely without formal support from Wesleyan Methodists in England or leadership on Wesley’s part. Captain Webb also ventured to other regions with new Methodist societies springing up throughout the middle colonies and upper South.114

During the 1760s, the promising religious field of America attracted evangelizing Methodists, since there were a number of denominations and a variety of new immigrants, especially in the middle colonies of New York, Pennsylvania, and Delaware. Unlike Methodists in England, American Methodists did not have to contend with a powerful and pervasive Church of England. While Methodists succeeded in some places where Anglicans were established, there were areas of America that were free of any religious authority altogether, and Methodism’s evangelical itinerant system was well suited to exploit these open areas.

Alongside Irish and English immigrants, one of the primary groups of early American Methodist converts was African Americans. African Americans began to join evangelicals in significant numbers during the latter part of the Great Awakening, when the South saw its greatest revivals in the 1760s with Separate Baptists groups springing up in Virginia. Methodist meetings and revivals began sweeping the Middle Atlantic and the South in the 1770s and then surged strongly at the turn of the nineteenth century. During the initial expansion of evangelical religion in the eighteenth century, slave populations were expanding as well, which facilitated acculturation of English language and customs into African American populations. Given the concentrated populations of slaves in the South, the oftentimes remote location of slaves, and their understandable aversion to groups that emphasized formal religious education (such as the Anglican and Presbyterian churches), evangelical sects were better suited to converting African Americans.115

In the Revolutionary period, white Methodist preachers were especially ardent in their pursuit of African American converts, who, historian Don Mathews argues, “were often more responsive to the evocative Methodist preaching than were whites.”116 African Americans’ increased attraction to evangelicalism had many causes, including the method and message of evangelicalism, its attention to spirituality, the primacy of the Bible, and congregational participation. Like evangelical revivals, traditional African spirituality was more participatory than traditional Christian churches; many African Americans contributed to the evangelical ethos of lay participation. The swapping of religious practices and influences between African Americans and European Americans was an ongoing, collaborative process. From the 1760s and 1770s onward, influenced by African American participation, Methodists promoted a responsive, physical form of worship, which included crying, shouting, singing, and stamping.117

Evangelical leaders began to consider African American communities as a previously untapped arena for new souls in the competitive religious marketplace.118 Robert Strawbridge, a gifted preacher who led Methodist societies in the upper South, had drawn a large number of African Americans to Methodist meetings in Maryland. In a society in Long Island that formed in 1768, black and white members were in exactly equal numbers. As Cynthia Lynn Lyerly writes, “Methodism was born in America as a biracial lay movement.”119 As Wesley’s dream of African conversion was finally starting to be realized in America by the 1760s, it was remarkably different from the missionary ideals espoused by the Society for the Propagation of the Gospel. The SPG envisioned formal catechisms as the basis for inculcating faith among non-Christians, but African Americans did not respond to this formal teaching, nor had the Anglican Church been terribly effective at convincing slaveholders to allow them access to slaves.120 While John and Charles Wesley initially saw African Americans as part of a wider and perhaps overly optimistic missionary evangelical project in the latter part of the 1730s, by the 1760s and 1770s, African American Methodists were central to the American Methodist connection.

Conclusions

The transcendence, sociability, and mobility of the Methodist organization were powerful ideas for African Americans. Slave and free African Americans could appreciate the transformative elements of conversion and transcendence of the physical world. The sociability of the Methodist family was a powerful element of association among African Americans and between white and black converts. The mobility of the itinerant preachers, particularly in the beginning of Methodist expansion in America, was central to its success at reaching populations that were not served by established churches. This was especially true for reaching slaves.

While the Wesley brothers did not see their time in America as an overwhelming success, it was clearly an important period for the birth of Methodism. From the 1730s and 1740s, when the Wesleys experimented with their missionary ideals, the transatlantic arena and its mobile populations were central to their formulations of Methodist practice. The early period of Methodism demonstrates its absorbent and ecumenical qualities. Methodists took in the social practices of religious meetings and experimented freely with various forms, keeping the bands and classes as central components in effective religious fellowship and as official forums for membership and discipline.

Early Methodists’ social orientation formulated a tenet that was central to this group’s success: while it drew the boundaries and discipline for belonging, it was also open to new members. It emphasized the certainty and benefits of belonging to this group, through having a ticket for class meetings and defining rules for living. They identified each other through these literal and material practices and by calling each other by family names. While their familial nature mattered, it was not a natal sense of belonging. One was not born into it; one had to earn it through commitment to true conversion and salvation. In many ways this is a profoundly eighteenth-century ideal, underlined by the universal promise of salvation. In the same way that true evangelical conversion pulled individuals out of their familial ties, conversion pulled individuals out of their bodily constraints and physical locations. Conversion made individuals members of a transnational and unearthly family, one in which members might not even meet in this world but were guaranteed to do so in the next.