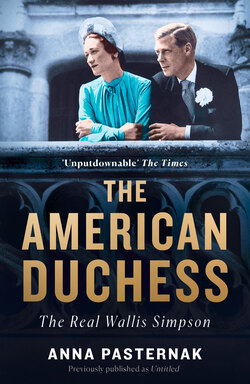

Читать книгу The American Duchess - Анна Пастернак - Страница 11

The Prince’s Girl

ОглавлениеAs the train hurtled north from St Pancras to Melton Mowbray in Leicestershire, Wallis Simpson stood in the aisle of a compartment, practising her curtsy. No mean feat, given the lurch and sway of the carriage. She was being instructed that the trick was to put her left leg well back behind her right one. Wallis’s balance was further challenged due to a streaming cold; her head was bunged up, while a voice rasped in her ears as she tried to master an elegant swoop down, then up. This comical scene was being watched by her husband, Ernest Simpson – always gently encouraging – and their friend Benjamin Thaw Jr, who was delivering the etiquette tutorial. Benjamin, known as Benny, first secretary at the United States embassy, was married to Consuelo Morgan, whose glamorous American half-sisters were Thelma, Viscountess Furness, and Gloria Vanderbilt.

Benny and Connie Thaw had become close friends of the Simpsons in London. Wallis and Ernest mixed in society circles thanks to the introductions of his sister, Maud Kerr-Smiley. Maud had married Peter Kerr-Smiley in 1905. He became a prominent Member of Parliament and it was the Kerr-Smileys who facilitated the Simpsons’ entrée into the upper echelons of the aristocracy. It was through Consuelo that Wallis first met Thelma Furness. Consuelo had told her sister that Wallis was fun, promising Thelma that she would like her. In the autumn of 1930, she took Wallis to her sister’s Grosvenor Square house for cocktails. ‘Consuelo was right,’ said Thelma. ‘Wallis Simpson was “fun”, and I did like her.’ ‘She was not beautiful; in fact, she was not even pretty,’ she recalled of thirty-four-year-old Wallis – who was accustomed to an ever-present scrutiny of her looks – ‘but she had a distinct charm and a sharp sense of humour. Her dark hair was parted in the middle. Her eyes, alert and eloquent, were her best feature.’ Wallis was blessed with riveting sapphire blue eyes.

That November, 1930, Wallis received a tantalising invitation. Connie Thaw asked her if she and Ernest would act as chaperones to Thelma and the Prince of Wales at a weekend house party in Leicestershire. Connie had to leave for the Continent at the last minute, due to a family illness, and wondered if Wallis and Ernest would accompany Ambassador Thaw to Burrough Court, Viscount Furness’s country house, instead. The Simpsons had heard the rumours that Thelma Furness was ‘the Prince’s Girl’, having stolen the maîtresse-en-titre role from his previous lover, Mrs Freda Dudley Ward. The prince’s pet name for Thelma was ‘Toodles’ and she was said to be madly in love with him. It was an open secret in society circles that Thelma was unhappily married to Marmaduke, the 1st Viscount Furness. Known as the ‘fiery Furness’, he had red hair and a temper.

Wallis’s first reaction to the invitation was ‘a mixture of pleasure and horror’. ‘Like everybody else, I was dying to meet the Prince of Wales,’ she said, ‘but my knowledge of royalty, except for what I had read, had until then been limited to glimpses at a distance of King George V in his State Coach on his way to Parliament.’ Though unsure of royal etiquette, she was at least confident of looking the part, having been on a shopping spree in Molyneux, Paris, a few months earlier. Her attractive blue-grey tweed dress, with a matching fur-edged cape, ‘would meet the most exacting requirements of both a horsy and princely setting’.

It was past five o’clock on Saturday afternoon when Thaw and the Simpsons arrived at Melton Mowbray, in the heart of fox-hunting country. A thick fog choked the county. Burrough Court was a spacious, comfortable hunting lodge full of traditional mahogany furniture and lively chintz. Thelma’s stepdaughter, Averill, greeted the guests, informing them that the rest of the party had been delayed out hunting on the road, due to the fog. Taken into the drawing room, where tea had been laid out on a round table in front of the fire, Wallis could feel her skin burning. Suspecting she had a slight temperature, she hankered to go to bed. Instead, they were forced to wait a further two hours until the royal party arrived.

After what seemed an age, voices were heard in the hallway and Thelma appeared with two princes: Edward, Prince of Wales, and his younger (favourite) brother, Prince George. To her surprise, Wallis’s curtsy to each prince came off well, to the Simpsons’ shared amusement. Thelma led everyone back to the table in front of the fire and they had tea all over again.

Like many who meet celebrities in the flesh for the first time, Wallis was taken aback; she was surprised by how small the Prince of Wales was. She was five foot five and Edward less than two inches taller. Prince George was ‘considerably taller’, she noted, ‘with neatly brushed brown hair, aquiline features, and dark-blue eyes. He gave an impression of gaiety and joie de vivre.’ Facially, Edward was immediately recognisable. ‘I remember thinking, as I studied the Prince of Wales, how much like his pictures he really was,’ she recollected. ‘The slightly wind-rumpled golden hair, the turned-up nose, and a strange, wistful, almost sad look about the eyes when his expression was in repose.’

At eight o’clock, Prince George’s friends arrived and took him to another house party. Finally, the Simpsons could retire upstairs to change. Wallis had a much longed-for hot bath and took two aspirin, while Ernest – from America but naturalised British – remarked on the charm of the two royal brothers and how they instantly put everyone at their ease. ‘I have come to the conclusion,’ he added, ‘that you Americans lost something that is very good and quite irreplaceable when you decided to dispense with the British Monarchy.’

The dinner party that night for thirty guests was late even by European standards, past ten o’clock. Ernest and Wallis knew no one and were at a conversational loss as they had no knowledge of, or curiosity about, hunting. A fact not lost on the prince. ‘Mrs Simpson did not ride and obviously had no interest in horses, hounds, or hunting in general,’ Edward later wrote. ‘She was also plainly in misery from a bad cold in the head.’ Discovering that she was American, the prince kicked off conversation by observing that she must miss central heating, of which there was a lamentable lack in British country houses and an abundance in American homes. Wallis’s response astonished him: ‘On the contrary. I like the cold houses of Great Britain,’ she replied. According to the prince ‘a mocking look came into her eyes’, and she replied: ‘I am sorry, Sir, but you have disappointed me.’

‘In what way?’ said Edward.

‘Every American woman who comes to your country is always asked the same question. I had hoped for something more original from the Prince of Wales.’

***

Wallis, born Bessie Wallis Warfield on 19 June 1896, took pride in coming from old Southern stock. ‘Wallis’s family was very old by American standards,’ said her friend, Diana, Lady Mosley, approvingly. Wallis’s mother, Alice, gave birth to her in a holiday cottage at Blue Ridge Summit in Pennsylvania, where she had gone with her consumptive husband, named Teackle, to escape the heat of his native Baltimore. Alice and Teackle, both twenty-six years old, were fleeing their disapproving parents. Wallis wrote that her mother and father had married in June 1895: ‘without taking their parents into their confidence, they slipped away’. Records show that they actually married on 19 November, seven months before her birth, in a quiet ceremony with no family present. Wallis was conceived out of wedlock, a fact she tried to blur in later accounts of her life. She recalled how she once asked her mother for the date and time of her birth ‘and she answered impatiently that she had been far too busy at the time to consult the calendar let alone the clock’. Wallis learned early the benefits of discretion.

Her mother was a Montague from Virginia. They were famous for their good looks and sharp tongues. When Wallis was growing up, if she made one of her familiar wisecracks, friends would exclaim: ‘Oh, the Montagueity of it!’ Perhaps it was a Montagueism that caused Wallis as a young child to drop the first name Bessie and say that she wished to be known simply as ‘Wallis’. She was ‘very quick and funny’, remembers Nicky Haslam. ‘She could be cutting too. She put people’s backs up amid the British aristocracy in the sense of being too bright and witty.’ On meeting Wallis, Chips Channon declared: ‘Mrs Simpson is a woman of great wit’, she has ‘sense, balance and her reserve and discretion are famous’. ‘Her talent was for people,’ said Diana Mosley. ‘Witty herself, she had the capacity to draw the best out of others, making even the dull feel quite pleased with themselves.’

From a young age, realising that she was not conventionally attractive, and could not rely on the flimsy currency of her looks, Wallis developed an inner resilience and astute insight. ‘My endowments were definitely on the scanty side,’ she later recalled. ‘Nobody ever called me beautiful or even pretty. I was thin in an era when a certain plumpness was a girl’s ideal. My jaw was clearly too big and too pointed to be classic. My hair was straight where the laws of compensation might at least have produced curls.’

Wallis’s father died from tuberculosis when Wallis was five months old, leaving her mother penniless. The Warfields supported Alice and their granddaughter, affording Wallis a happy childhood. An only child, she plainly adored her mother, who summoned up ‘reserves of will and fortitude’ to surmount her single-mother status. Wallis admired her mother for never ‘showing a trace of self-pity or despair’ – characteristics that she inherited and would employ throughout her own life with similar aplomb. Alice urged Wallis never to be afraid of loneliness. ‘Loneliness has its purposes,’ she counselled her daughter. ‘It teaches us to think.’

Wallis and her mother were so close that Wallis described their relationship as ‘more like sisters’, in terms of their ‘comradeship’. Alice Warfield was both loving and strict. If Wallis swore, she would be marched to the bathroom to have her tongue scrubbed with a nailbrush. When Wallis was apprehensive about learning to swim, her mother simply carried her to the deep end of a swimming pool and dropped her in. ‘Then and there I learned to swim, and the thought occurs that I’ve been striking out that way ever since,’ Wallis wrote years after Edward VIII’s abdication.

When Alice first met Ernest Simpson, she warned her future son-in-law: ‘You must remember that Wallis is an only child. Like explosives, she needs to be handled with care. There are times when I have been too afraid of having put too much of myself into her – too much of the heart, that is, and not enough of the head.’ Alice sent Wallis to a fashionable day school in Baltimore, where Wallis was a diligent student. ‘No one has ever accused me of being intellectual. Though in my school days I was capable of good marks,’ she said. As a young girl, Wallis was already tiring of her unsettled life and ‘desperately wanted to stay put’. This desire to find a stable home would become a constant theme in her life, heightened when forced into exile with the Duke of Windsor. For a few years Wallis and her mother lived with her Warfield grandmother, then with her Aunt Bessie, until Alice, craving a place of her own, took a small apartment when her daughter was seven. Wallis loved her grandmother’s Baltimore house: ‘a red brick affair, trimmed with white with the typical Baltimore hall-mark, white marble steps leading down to the side-walk’. Here her grandmother lived with her last unmarried son, S. Davies Warfield – ‘Uncle Sol’ to Wallis. ‘For a long and impressionable period he was the nearest thing to a father in my uncertain world,’ Wallis recalled. ‘But an odd kind of father – reserved, unbending, silent. I was always a little afraid of Uncle Sol.’

A successful banker, Sol paid the school fees until Wallis’s mother married again. Alice’s new husband was John Freeman Rasin, who was prominent in politics and fairly wealthy. While offering financial security, he took Alice to live part time in Atlanta, which was a wrench for Wallis. She was sent to boarding school – Oldfields – in 1912 where the school motto, pasted on the door of every dormitory, was ‘Gentleness and Courtesy are expected of the Girls at all Times’. Wallis’s best friend at Oldfields was Mary Kirk, who was later to play an astonishing part in her life.

In 1913, Wallis and her mother suffered another shock. Freeman Rasin died of Bright’s disease, a failure of the kidneys. Wallis was heartbroken to see her mother so distressed. ‘It was the first time I had ever seen her dispirited.’ Wallis would never forget her mother whispering to her: ‘I had not thought it possible to be so hurt so much so soon.’ Alice had been with her second husband for less than five years.

Wallis left Oldfields in 1914, signing her name in the school book with the bold and rebellious ‘ALL IS LOVE’, and made her debut as part of the jeunesse dorée at the Bachelors’ Cotillion, a ball in Baltimore, on 24 December. (To be presented at the ball was ‘a life-and-death matter for Baltimore girls in those days’, maintained Wallis.) The Great War had begun in Europe in August, and the US daily newspapers were ‘black with headlines of frightful battles’. Baltimore’s sentiments were firmly on the side of the Allies and the thirty-four debutantes attending the ball were instructed to sign a public pledge to observe, for the duration of the war, ‘an absence of rivalry in elegance in respective social functions’. This was, according to Wallis, an attempt to set an example of how young American women should conduct themselves at a time when other friendly nations were in extremity.

Unable to afford to buy her ball gown from Fuechsl’s, Baltimore’s most fashionable shop, like most other debutantes, Wallis designed her own dress. White satin with a white chiffon tunic and bordered with seed pearls, it was made by ‘a local Negro seamstress called Ellen’. Wallis’s mother permitted her for the first time a brush of rouge on her cheeks, even though rouge ‘was considered a little fast’. Wallis’s love of couture would become legendary; as the Duchess of Windsor, she became an icon of style and an arbiter of meticulous taste. She regularly featured in the best dressed lists of the world. Her sharp eye for fashionable detail burgeoned early. According to Aunt Bessie, Wallis created a ‘foot-stamping scene’ at one of the first parties she ever attended as a little girl, when she wanted to substitute a blue sash her mother wanted her to wear, with a red one. ‘I remember exactly what you said,’ Aunt Bessie later told Wallis. ‘You told your mother you wanted a red sash so the boys would notice you.’ Wallis told a fashion journalist in 1966: ‘Whatever look I evolved came from working with a little dressmaker around the corner years and years ago, who used to make all my clothes. I began with my own personal ideas about style and I’ve never felt correct in anything but the severe look I developed then.’

As the Duchess of Windsor, she created an eternal signature style, which became her personal armour. Her dedication to appearance defined her as a Southern woman, hailing from an era when a woman dressed to please her man. ‘She was chic but never casual,’ said the French aristocrat and designer Jacqueline de Ribes, who similarly topped the best dressed lists. ‘Other American society women, like Babe Paley, could be chic in blue jeans. The duchess was a different generation.’ Elsa Maxwell observed: ‘The Duchess has impeccable taste and she spends more money on her wardrobe than any woman I’ve ever known. Her clothes are beautiful and chic, but though she invests them with elegance, she wears them with such rigidity, such neatness, that she destroys the impression of ease and casualness. She is too meticulous.’ Diana Vreeland, later of Harper’s Bazaar and editor of Vogue, described Wallis’s style as ‘soignée, not degageé’ – polished but not relaxed.

Wallis learned to distil every outfit to its essence, later asking Parisian couturiers, including Hubert de Givenchy and Christian Dior’s Marc Bohan, to dispense with pockets. Yet in her choice of nightwear she was the essence of soft, traditionally feminine sensuality. Diana Vreeland, who had an exclusive lingerie boutique off Berkeley Square in London in the mid-1930s, recalled that when Wallis shopped, ‘she knew exactly what she wanted’. One day, in autumn 1936, just before the king’s abdication, Wallis ordered three exquisite nightgowns to be made in three weeks. ‘First, there was one in white satin copied from Vionnet, all on the bias, that you just pulled down over your head,’ said Vreeland. ‘Then there was one I’d bought the original of in Paris from a marvellous Russian woman. The whole neck of this nightgown was made of petals, which was too extraordinary, because they were put in on the bias, and when you moved they rippled. Then the third nightgown was a wonderful pale blue crêpe de Chine.’

Years after the abdication, Elsa Maxwell asked Wallis why she devoted so much time and attention to her clothes. Was it not a frivolous pursuit when she had so many other responsibilities and her extravagance merely invited criticism? Wallis replied candidly: ‘My husband gave up everything for me. I’m not a beautiful woman. I’m nothing to look at, so the only thing I can do is to try and dress better than anyone else. If everyone looks at me when I enter a room, my husband can feel proud of me. That’s my chief responsibility.’

‘Wallis was a much more artistic creature than people thought,’ said Nicky Haslam. ‘She liked beautiful things and had a keen eye.’ Haslam, who worked on American Vogue in the 1960s, was introduced to Wallis in New York by the magazine’s social editor, Margaret Case. ‘We were seated at a booth at the back of the Colony restaurant in New York, on the best banquette, and in walked the duchess,’ he recalled. ‘Every single head turned to look at her and cutlery literally dropped. She was wearing an impossibly wide pink angora Chanel tweed with a black grosgrain bow at her nape. At the end of a wonderful lunch, she took a discreet peek at her watch, which was tied to her bag on a delicate chain. It was Fulco Verdura* who told her that it was common for women to wear a watch.’

Having the sartorial edge hugely increased Wallis’s confidence. Of her first meeting with the Prince of Wales at Melton Mowbray, she said her clothes would give her ‘the added assurance that came from the knowledge that in the dress was a little white satin label bearing the word Molyneux’.

***

It was her sister-in-law, Maud, who suggested that Wallis should be presented at court on 10 June 1931. Ernest Simpson’s rank as a captain with the Coldstream Guards gave him the requisite social status, but Wallis was reluctant to go. Once again, as for her debutante ball in her youth, she did not have the funds to buy the splendid clothes the occasion demanded. However, Wallis’s friends persuaded her that she would be foolish to turn down the generous offer of her girlfriend, Mildred Andersen, to present her. ‘Determined to get through the ceremony in the most economical manner,’ she wore the dress that Connie Thaw herself had worn to be presented, while Thelma Furness lent her the train, feathers and fan. She treated herself to a large aquamarine cross and white kid three-quarter-length gloves, writing to her Aunt Bessie that her aquamarine jewellery looked ‘really lovely on the white dress’.

Of the magnificent pageantry of the event, what impressed Wallis ‘to the point of awe’ was the grandeur that invested King George V and Queen Mary, sitting side by side in full regalia on identical gilt thrones on their red dais. Standing behind the two thrones were the Prince of Wales and his great-uncle, the Duke of Connaught. Ernest Simpson, in his uniform of the Coldstream Guards, looked on proudly as Wallis and Mildred performed deep curtsies to the sovereign, then to the queen. The Prince of Wales later recalled of Wallis: ‘When her turn came to curtsey, first to my father and then to my mother, I was struck by the grace of her carriage and the natural dignity of her movements.’ After the ceremony, Wallis was standing with Ernest in the adjoining state apartment, in the front row, watching as the king and queen walked slowly by, followed by other members of the royal family. As the Prince of Wales passed her, Wallis overheard him say to his uncle: ‘Uncle Arthur, something ought to be done about the lights. They make all the women look ghastly.’

That evening, at a party hosted by Thelma Furness, Wallis met the Prince of Wales again. Over a glass of champagne, he complimented Wallis on her gown. ‘“But, Sir,” she responded with a straight face, “I understood that you thought we all looked ghastly.”’ The prince ‘was startled’, Wallis noted with some satisfaction. ‘Then he smiled. “I had no idea my voice carried so far”.’

The prince was captivated. No British woman would have dreamed of speaking to him in such a direct and provocative way. ‘In character, Wallis was, and still remains, complex and elusive,’ he wrote of that encounter. ‘From the first I looked upon her as the most independent woman I had ever met.’

***

Prince Edward was born on 23 June 1894 at White Lodge, Richmond Park, the home of his parents, the Duke and Duchess of York. An extraordinary prophecy was made about the great-grandson and godson of Queen Victoria, the queen then aged seventy-five and in the fifty-seventh year of her reign. The socialist pioneer Keir Hardie rose in the House of Commons to shatter the polite rejoicing about the royal birth. Instead, he hollered: ‘This boy will be surrounded by sycophants and flatterers by the score and will be taught to believe himself as of a superior creation … in due course … he will be sent on a tour round the world, and probably rumours of a morganatic alliance will follow, and the end of it all will be that the country will be called upon to pay the bill.’ As a predictor of Edward’s royal destiny, the Scot proved uncannily prescient.

Baptised by the Archbishop of Canterbury from a golden bowl of holy water from the River Jordan, in the presence of Queen Victoria, ‘David’, as his family always called him, would experience a strict, unhappy and largely loveless childhood. His mother showed little maternal warmth to her six children. While her husband, who in 1910 became King George V, was even more severe. A dogged disciplinarian, with rigid rules on dress and protocol, he ensured that any errant childish behaviour was bullied and beaten out of his offspring. ‘My father was the most terrible father, most terrible father you can imagine,’ Edward’s brother, Prince Henry, later said. ‘He believed in God, in the invincibility of the Royal Navy, and the essential rightness of whatever was British,’ said Edward. Handwritten on his father’s desk were the words that Edward was made to memorise as a young boy: ‘I shall pass through this world but once. Any good thing, therefore, that I can do or any kindness that I can show any human being, let me do it now. Let me not defer nor neglect it for I shall not pass this way again.’ These were the lines of an early nineteenth-century American Quaker, Stephen Grellet.

As a sense of duty and responsibility cleaved through every aspect of his royal bearing, the Duke of York made Edward fully aware of the influence of his great-grandmother, Queen Victoria. Her children and grandchildren ruled the courts of Europe. Her eldest daughter, Victoria, was the Dowager Empress of Germany; Kaiser Wilhelm II was the queen’s grandson, and the Tsar of Russia, Nicholas II, was her grandson by marriage. The empire over which Queen Victoria ruled was the most powerful in the world; it embraced a quarter of the earth’s surface and nearly a quarter of its population. On her death in 1901, this empire passed to her eldest son Edward VII and then to George. An empire Edward VIII would inherit, albeit briefly.

As Edward later wrote of his childhood: ‘For better or worse, royalty is excluded from the more settled forms of domesticity … The mere circumstances of my father’s position interposed an impalpable barrier that inhibited the closer continuing intimacy of conventional family life.’ Despite having five siblings, and being particularly close to Bertie and later, George, his younger brother by eight years, Edward recalled that: ‘We were lonely in a curious way.’ Denied association with other children their own age and home-educated by uninspiring tutors, behind the turreted facades of the royal households, there was emotional sterility. ‘Christmas at Sandringham,’ Edward reflected, ‘was Dickens in a Cartier setting.’ The writer James Pope-Hennessy described Sandringham as ‘a hideous house with a horrible atmosphere in parts, and in others no atmosphere at all. It was like a visit to a morgue.’ The Hon. Margaret Wyndham, who served as Woman of the Bedchamber to Queen Mary from 1938, recalled: ‘At Sandringham if the king were present they put on Garter ribbons, tiaras and diamonds for every family dinner even without guests.’ Freda Dudley Ward later said of the prince’s childhood: ‘If his life was a bit of a mess, his parents were to blame. They made him what he was. The duke hated his father. The king was horrible to him. His mother was horrible to him, too … The duke loved his mother but his mother wouldn’t let him love her. She always took the king’s side against him.’

In 1907, twelve-year-old Edward was dispatched, in tears, to the Royal Naval College at Osborne on the Isle of Wight with the bizarre assurance from his father that: ‘I am your best friend.’ Edward quickly settled in as a cadet. His letters home were full of boyish excitement: he wrote to his parents of meeting the explorers Sir Ernest Shackleton and Captain Robert Falcon Scott and he performed in a pantomime. Instead of inheriting his father’s unassailable sense of duty, a duty that was ‘drilled into’ him, Edward, burdened by his regal inheritance, longed to break free. Even as a young boy he said that he ‘never had the sense that the days belonged to me alone’. Edward progressed to officer training at Dartmouth Royal Naval College, where he struggled academically – he came bottom of his year – but proudly reported to his parents that he was ‘top in German’. Perhaps the only thing he excelled in as a boy was German, learning first from his German nursemaid and then Professor Eugene Oswald, an elderly master who had previously taught his father the language. ‘I liked German and studied diligently,’ he said, ‘and profited from the hours I spent with the professor.’

The death of King Edward VII on 6 May 1910, after a reign of nine years, interrupted Edward’s summer term at Dartmouth for three weeks. Now heir apparent, he was called home to Windsor for his sixteenth birthday. His father informed him that he was going to make him Prince of Wales (the king’s eldest son does not automatically become Prince of Wales; he is anointed by the monarch when deemed appropriate). Edward returned to Dartmouth with a new title, the Duke of Cornwall, and considerable wealth from the Duchy of Cornwall estate. For the first time he had an independent income. ‘I do not recall that this new wealth gave rise to any particular satisfaction at the time,’ he said.

In his last term at Dartmouth, both Edward and Bertie (who had followed his brother’s trajectory from Osborne to Dartmouth, where Edward had ‘assumed an older brother’s responsibility for him’) caught a severe case of mumps, followed by measles. Two-thirds of cadets were hospitalised in this epidemic. It is believed that Edward then developed orchitis, a complication of mumps that left him sterile. The knowledge that Edward would not be able to produce an heir may have been significant later, in the establishment’s push to have brother Bertie (George VI) as king.

The coronation of George V in June 1911 thwarted Edward’s ‘first serious ambition’. He was forced to forgo the goal of his officer-cadet life and miss a training cruise in North American waters. After completing his naval training, Edward underwent a ‘finishing’ programme in preparation for his future full-time role as Prince of Wales. Assumed to be studying for Oxford, while his parents travelled to India for the coronation durbar, Edward instead opted to play cards with his grandmother, Queen Alexandra, and helped her with jigsaw puzzles. Nevertheless, Edward went up to Magdalen College, Oxford, in October 1912. Befitting the future king, he had a special suite of rooms installed for him, including his own bath in the first private undergraduate bathroom.

Missing the camaraderie of his Royal Navy friends, he was ‘acutely lonely’ and ‘under the added disadvantage of being something of a celebrity’. He soon realised that the skills he had acquired in the navy, which included an ability to ‘box a compass, read naval signals, run a picket boat, and make cocoa for the officer of the watch’, held little sway with learned Oxford dons. The Prince was tutored by the most eminent scholars, including Magdalen’s esteemed president, Sir Herbert Warren, but Oxford did nothing academically for him. Personally, he seemed uncertain of himself; encouraging familiarity from fellow undergraduates, then swiftly acting with regal hauteur. He found himself happiest on the playing fields, discovering at Oxford a love of sport; he played football, cricket and squash. He beagled with the New College, Magdalen and Trinity packs, took riding lessons – progressing to become a fearless horseman. He punted, gambled, smoked, drank to excess and even smashed glasses and furniture as part of the high jinks of the Bullingdon Club – a club which, the New York Times explained to its readers, represented ‘the acme of exclusiveness at Oxford; it is the club of the sons of nobility, the sons of great wealth; its membership represents the “young bloods” of the university’.

Like Wallis, Edward displayed a strong early interest in fashion, developing his own flamboyant style. Rather than starchy formal garb, he preferred an eccentric mix of sports coats, loud ‘Prince of Wales checks’ (named after his grandfather, but popularised by Edward), bright tartans, baggy golfing plus fours and boyish Fair Isle sweaters. This was to become a source of conflict with his sartorial stickler of a father. When Edward entered the breakfast room at Buckingham Palace one morning, proudly sporting a suit with the new style of trouser turn-ups, the king bellowed: ‘Is it raining in here?’

‘Edward was completely different to any of the rest of the family,’ recalled John Julius Norwich, who, as a young man, knew both Edward and Wallis. ‘George V was very stiff and regal yet here was his son, a boy in a peaked cap, smoking and winking.’ The young prince ‘was dandyish and out to shock’, said David Maude-Roxby-Montalto di Fragnito. ‘He wanted to break tradition. He wore his signet ring in the continental way, just to be different. The British wear it facing inwards, to use on seals, whereas the Europeans wear it facing out. It was very arriviste of the prince to wear his continental style as no British gentleman would ever have done this.’

During his Easter and summer vacations in 1913, Edward went to visit his German relatives. ‘The purpose of these trips was to improve my German and to teach me something about these vigorous people whose blood flows so strongly in my veins. For I was related in one way or another to most of the many Royal houses that reigned in Germany in those days,’ Edward wrote. Later in life, ‘the duke loved to sit with my wife and speak perfect German (with a slight English accent) for hours with her’, recalled Count Rudolf von Schönburg, husband of Princess Marie Louise of Prussia, who was related to Edward through Queen Victoria. ‘Nothing made him happier than speaking at length about his German relations, to whom he was very close. He was very pro-German and would have liked to avoid a war between the two countries.’

‘Later in his life, the prince lived in France for over fifteen years, yet he never spoke a word of French,’ said John Julius Norwich. ‘He would start a conversation with a Frenchman in German. As you can imagine, his fluent German did not go down well in 1946 in France. To him, there was English and there was “foreign” and his “foreign” was German. The prince really was incredibly stupid.’

Edward left Oxford before taking his finals and seemingly without the slightest intellectual curiosity, claiming: ‘I have always preferred outdoor exercise to reading.’ He was now fully confirmed as the playboy bachelor prince. Painfully thin, he subjected himself to punishing physical regimes throughout his twenties and thirties. He liked to sweat a lot – he wore five layers to exercise – then party into the early hours, existing on minimal sleep and even less food. According to Lord Claud Hamilton, the Prince of Wales’s equerry from 1919–22, Edward took after his mother who, ‘frightened of becoming fat, ate almost nothing at all’. Her ladies-in-waiting regularly went hungry as meals consisted of tiny slivers of roast chicken, no potatoes, a morsel of vegetables, followed by a wafer.

Edward loathed Buckingham Palace so much, with its ‘curious musty odour’, that he refused to take meals there and only ate an orange for lunch. This became his daily routine. ‘His amazing energy makes him indulge frantically in exercise or stay up all night,’ observed Chips Channon. Boyish and hyper-energetic, Edward never had to shave and preferred nightclubs to formal society. Like a more sophisticated Bertie Wooster, he even took up the banjulele. His favourite question to courtiers was the decidedly un-royal, rebellious teenage riposte: ‘Can I get away with it?’

‘The late king and queen are not without blame,’ Chips Channon wrote at the time of Edward’s abdication in 1936. ‘For the twenty-six years of their reign, they practically saw no one except their old courtiers, and they made no social background whatever for any of their children. Naturally, their children had to find outlets and fun elsewhere, and the two most high-spirited, the late king (Edward) and the fascinating Duke of Kent (George) drank deeply from life.’ Edward partied his way through the last London season before the outbreak of the Great War with gusto. With his angelic looks, electric charm and personality dedicated to pleasure not pomp, he infuriated his parents with his dilettante behaviour.

Yet when Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August 1914, Edward was desperate to unveil his courage and serve his country. Commissioned into the Grenadier Guards, he was vexed to find himself denied a combat role. It was a bitter blow – ‘the worst in my life’ he said later. Sent to France in 1914, he was kept well behind enemy lines at general headquarters, reduced to conducting basic royal duties such as visits and meeting and greeting dignitaries. Complaining he was the one unemployed man in northern France, he did eventually manage to get into the battle zone where he observed the horrors of trench warfare. The fighting on the Somme, he wrote in a letter home, was ‘the nearest approach to hell imaginable’. In 1915, a shell killed his personal chauffeur.

‘Manifestly I was being kept, so to speak, on ice, against the day that death would claim my father,’ Edward wrote, expressing his mounting frustration. ‘I found it hard to accept this unique dispensation. My generation had a rendezvous with history, and my whole being insisted that I share the common destiny, whatever it might be.’ When he was promoted to captain and awarded the Military Cross, Edward’s feelings of unworthiness and self-loathing spiralled. He wrote to his father on 22 September 1915: ‘I feel so ashamed to wear medals which I only have because of my position, when there are so many thousands of gallant officers who lead a terrible existence in the trenches who have not been decorated.’

By the end of the war, which saw the collapse of the Romanov, Hohenzollern, Habsburg and Ottoman dynasties, the Prince of Wales seemed ordained to protect the House of Windsor. It was during the Great War that King George decided that, due to anti-German sentiment in Britain (according to the popular press, even dachshunds were being pelted in the streets of London), the royal family must change their Germanic-sounding surname. Saxe-Coburg-Gotha became Windsor.

From the war years onwards, throughout his twenties and early thirties, Edward did his duty, dazzling the world as the fairy-tale prince. He visited forty-five countries in six years, travelling 150,000 miles. On a trip to Canada, his right hand became so badly bruised and swollen from too many enthusiastic greetings (which he described as pump-handling), that he was forced to proffer his left hand for fear of permanent impairment. Adored and feted like a film star, Edward began to behave like one too. His mood swings became all too familiar amongst his equerries and advisors, as he oscillated between buoyed-up exhilaration and lacerating self-pity. He became irritated with official rigmarole and seemed unable to focus on diplomatic matters. On Christmas Day 1919, before embarking on a five-month trip to the Antipodes, he wrote to his private secretary, Godfrey Thomas: ‘Christ how I loathe my job now and all the press “puffed” empty “success”. I feel I’m through with it and long to die. For God’s sake don’t breathe a word of this to a soul. No one else must know how I feel about my life and everything … You probably think from this that I ought to be in the madhouse already … I do feel such a bloody little shit.’

Another cause of friction with his parents was Edward’s obsession with nightclubs and partying in the burgeoning Jazz Age. King George wrote to Queen Mary of his horror, having heard reports that Edward danced ‘every night & most of the night too’, fearing that ‘people who don’t know him will begin to think that he is either mad or the biggest rake in Europe’.

Edward found some solace in his romantic life, yet here too, he was irreverent. Instead of seeking a suitable single, eligible bride with whom to settle down, he quickly established a penchant for married women. The patience of his advisors was wearing thin. Tommy Lascelles wrote: ‘For the ten years before he met Mrs Simpson, the Prince of Wales was continuously in the throes of one shattering and absorbing love affair after another (not to mention a number of street-corner affairs).’ It was Lascelles’s contention that the prince never grew up; that he remained morally arrested. Stanley Baldwin agreed: ‘He is an abnormal being, half child, half genius … It is almost as though two or three cells in his brain had remained entirely undeveloped while the rest of him is a mature man.’

Perhaps this partly explains the prince’s preference for married women, and his desire that they play a bossy, maternal role. His first serious relationship was with the British-born socialite, Mrs Freda Dudley Ward, who was half American and had two teenage daughters, Penelope (Pempe) and Angela (Angie), on whom Edward doted. Between March 1918, when the prince first met Mrs Dudley Ward sheltering in the doorway of a house in Belgrave Square during an air raid, and January 1921, the prince wrote her 263 letters. In total, during their relationship, which lasted over a decade (surviving his affair with Thelma Furness but not his infatuation with Wallis), the prince penned over two thousand letters to Freda Dudley Ward, many addressing her as ‘my very own darling beloved little mummie’. ‘It is quite pathetic to see the prince and Freda,’ Winston Churchill observed, after travelling with them on a train. ‘His love is so obvious and undisguisable.’

‘Freda, whom I knew, was like Wallis in that physically, she was fairly boyish. As far as their relationship went, the prince was a masochist who liked harsh treatment,’ said Nicky Haslam. ‘Freda was lovely,’ recalled John Julius Norwich. ‘She was the prince’s mistress … and everybody liked her.’ Chips Channon described her in his diaries as ‘tiny, squeaky, wise and chic’. ‘Mrs Dudley Ward was the best friend he ever had, only he didn’t realise it,’ said his brother, Prince Henry. Later in life, Mrs Dudley Ward was asked if her first husband, William Dudley Ward, minded about her affair with the Prince of Wales. ‘Oh, no,’ she replied. ‘My husband knew all about my relationship with the prince. But he didn’t mind. If it’s the Prince of Wales – no husbands ever mind.’

A hint of Edward’s desire to be dominated in his relationships lies in a letter he wrote to Freda on 26 March 1918. ‘You know you ought to be really foul to me sometimes sweetie & curse & be cruel. It would do me the world of goods and bring me to my right senses!! I think I’m the kind of man who needs a certain amount of cruelty without which he gets abominably spoilt & soft!! I feel that’s what’s the matter with me.’

***

Wallis Warfield was twenty years old when, in November 1916, she married her first husband, Earl Winfield Spencer Jr. She had first met the US Navy pilot the previous April during a trip to Florida, when he was stationed at the Pensacola Air Station. The day after she arrived at Pensacola Wallis wrote to her mother: ‘I have just met the world’s most fascinating aviator.’ Ever since she left Oldfields, Wallis, like her contemporaries, aspired to marriage as the sine qua non of achievement. When ‘Win’, dark-haired with brooding looks, proposed eight weeks after their meeting, Wallis was excited to be one of the first debutantes of her coming-out year to get engaged. As much as Wallis thought that she loved Win, a man she barely knew, she later admitted: ‘There also lay in the back of my mind a realisation that my marriage would relieve my mother of the burden of my support.’

Despite her mother’s fears that a navy life, with no permanent home, constant postings, little money, as well as long and lonely waits for her husband to return from sea, would be too regulated for someone as spirited as her daughter, Alice eventually gave the union her blessing. If only she had not. Wallis discovered on her short, grim honeymoon with Win at a hotel in West Virginia that he was an alcoholic. Wallis – who had only ever had a small glass of champagne at Christmas, as her puritanical family extolled the evils of alcohol – had never tasted hard liquor. West Virginia was a dry state, which further incensed Win, who pulled a bottle of gin from his suitcase. Once inebriated he would become aggressive, cruel and violent.

Her new life as a navy wife, first in San Diego, and then when Win took a desk job in Washington DC, became unbearable. Win’s insecurity, frustration at his dwindling career and jealous rages were sadistically vented on his young bride. But when Wallis decided to leave and seek a divorce, her mother was aghast. No Montague had ever been divorced. It was unthinkable. Even her stalwart Aunt Bessie said that it was out of the question. Her Uncle Sol was apoplectic. ‘I won’t let you bring disgrace upon us,’ he shouted.

Wallis persevered with the marriage. Her mother cautioned her that ‘being a successful wife is an exercise in understanding’. Wallis retorted bitterly: ‘A point comes when one is at the end of one’s endurance. I’m at that point now.’ She moved in with her mother, who was also living in Washington. As Uncle Sol refused her any financial help towards a divorce, her prospects looked bleak. Wallis was suitably thrilled when, in 1924, her cousin Corinne Mustin invited her to go on her first trip to Europe, to Paris. Win continued to write to Wallis and told her that he had been stationed in the Far East. He begged her to join him in China. Perhaps because Wallis could not afford a divorce and was uncertain of her financial and domestic future, she decided to give the marriage yet another go. Win met her in Hong Kong and soon enough, the familiar patterns recommenced. He became jealous, moody, quarrelsome and offensive. When he began drinking before breakfast, Wallis finally had had enough. She drew their eight-year marriage to a close, seeking a divorce at the United States Court for China in Shanghai.

‘Wallis was now twenty-eight and her character was formed,’ according to Diana Mosley. ‘She was independent but not tough, rather easily hurt with a rare capacity for making friends wherever she went. She was intelligent and quick, amusing, good company; an addition to any party with her high-spirited gaiety.’

Wallis embarked on a year’s sojourn in Peking, staying with her good friends Katherine and Herman Rogers. She later described her Eastern sojourn as her ‘Lotus Year’. As a divorced woman travelling in the Far East on her own, she displayed a spirited independence ahead of her time. According to a friend of Duff Cooper’s in Paris, a French woman who knew Wallis as Mrs Spencer in Peking, Wallis was ‘always good-natured’. Unfortunately, when news of Wallis’s relationship with the Prince of Wales broke in 1936, her year in China was used against her. It was said that she had visited the ‘singing houses’ of Shanghai and Peking. Unsavoury gossip tut-tutted, suggesting that she had acquired ‘sophisticated sexual techniques’ which she then used to entrap and manipulate the Prince of Wales and she became the butt of cheap jokes: ‘Other girls picked up pennies but Wallis was so proficient that she picked up a sovereign.’

Wallis nursed a secret that hit at the very heart of her femininity. She was infertile and had never menstruated. As a young girl it is unlikely that Wallis would have known that anything was wrong. Perhaps the absence of periods would have been her first sign at puberty that all was not as expected. It has been speculated that Wallis may have had a ‘disorder of sexual development’ or DSD, a modern term encompassing a wide range of rare genetic conditions. Others have claimed Wallis may have had Androgen Insensitivity Syndrome – that is, she was born genetically male, with the XY chromosome. If this had been the case, the male sexual organs would have been internal and barely noticeable and she would have had an extremely shallow vagina. Yet this is unlikely as Wallis lacked other physical traits associated with the syndrome. We also know that she would go on to have a hysterectomy in middle age.

Whatever the cause of Wallis’s infertility it was a source of profound sadness for her. Over three marriages she bore no children, but not out of choice. Though she and Edward seemed to adore children, their lack of parenthood united them as outsiders to a familial club. Instead, they lavished love on their dogs which became their child replacements. Wallis later wrote that she mourned never being part of the ‘miracle of creation’ and that her ‘one continuing regret’ was never having ‘known the joy of having children’. The secret inner pain of childlessness must have made the gossip and slurs against her so much harder to bear.

One of the reasons that Wallis kept herself skeletally thin was that she worried that if she put on any weight she would ‘bulk up in a masculine way’. Diana Mosley said that Wallis ‘loved and appreciated good food, but ate so little that she remained triumphantly thin at a time when slenderness was all important in fashion’. Elsa Maxwell agreed that Wallis ate very little at the dinner table. When she challenged Wallis about this, she always replied defensively: ‘I’m an ice-box raider.’ Clearly any snacking was confined to minuscule amounts. Wallis and Edward were similar in this respect; they both favoured starvation diets and punishing regimes, each obsessed with retaining an almost pre-pubescent slenderness.

Wallis expressed a traditional femininity through her clothes: her sartorial perfectionism – a love of Cartier and couture – served to create an exaggeratedly feminine outline that was more elegant than sexual. Always immaculately groomed, there was a delicacy about her appearance – from her skirts and dresses cinched-in at the waist with tiny belts, to neat little pairs of heels. Adorned as he was with exquisite statement jewels, there was nothing androgynous about Wallis’s style. She certainly was no ‘sex siren’ or ‘harlot’, as many made her out to be. Although Wallis often liked to be the centre of attention socially, in other ways she came across as old-fashioned and reserved; indeed, her upbringing in Baltimore had been ladylike to the point of prudish. Astonishingly she told Herman Rogers, who eventually gave her away at her wedding to Edward in 1937, that she ‘had never had sexual intercourse with either of her two husbands’. Nor had she ‘ever allowed anyone else to touch her below’ what she described as ‘her personal Mason–Dixon line’.†

Both Wallis and Edward shared insecurities about their sexual identities. Confiding this in one another may have helped forge a strong secret bond between them. Cynthia Jebb, Lady Gladwyn, whose husband was ambassador to France 1954–60, knew the Windsors in Paris and confided to Hugo Vickers that ‘the prince had sexual problems. He was unable to perform’ – she ‘called it a hairpin reaction. She said that the duchess coped with it. I commented: “She was meant to have learned special ways in China.” “There was nothing Chinese about it,” said Lady Gladwyn. “It was what they call oral sex.”’ Although she could be openly flirtatious in a social setting, Wallis was, as Nicky Haslam observed of her, sassy rather than sexy: her gaiety was more playful teasing than predatory or seriously seductive. ‘Wallis wasn’t obsessed by sex,’ says Haslam. ‘If anything, she was rigidly undressable in that she was prudish. Everybody made such a thing of her going to brothels in China but everyone did that in those days. It was the fashionable thing to do. To have a good look.’

‘It was just the sort of thing that the press would say, that she was a twice-divorced American adventuress out for what she could get,’ said John Julius Norwich. ‘Everything was a bid to discredit her but she was the furthest thing from kinky. You never got the feeling that she was particularly sexually motivated. She was a perfectly normal American woman but not in the least bit depraved. And there was nothing more normal than Ernest Simpson and he fell in love with her.’

Winston Churchill summed up the controversial couple’s mutual attraction: ‘the association was psychical rather than sexual, and certainly not sensual except incidentally’. Churchill always believed that Wallis was good for Edward; he defended the couple to the last. ‘Although branded with the stigma of a guilty love, no companionship could have appeared more natural, more free from impropriety or grossness,’ he said.

***

Wallis met Ernest Simpson through Mary Kirk, who had now become Madame Raffray, on her marriage to the Frenchman, Jacques Raffray. Raffray, a veteran of the Great War, had originally come to America to train US troops to fight in France. Wallis, then living in Washington, enjoyed staying with the Raffrays at their New York apartment. She spent Christmas of 1926 with them awaiting her divorce from Win. Ernest, who was also in the process of getting divorced, from his American wife Dorothea, with whom he had a daughter, Audrey, was frequently asked for dinner or to make up a fourth for bridge. A friendship developed and when both were granted divorces, Ernest asked Wallis to marry him.

A graduate of Harvard, Ernest had been born in New York of an American mother and a British father. After brief service as a captain in the British Army, he began work in the family shipping business, Simpson, Spence & Young. Tall, with blue eyes and a neat moustache, he was a fastidious dresser. In the early 1920s he was much in demand on the London scene and a regular dance partner of Barbara Cartland. (She later described him as a ‘handsome young bachelor, who was to figure dramatically in the history of England seventeen years later’.) The letter Wallis wrote to her mother on 15 July 1928 regarding Ernest’s marriage proposal is revealing: ‘I’ve decided that the best and wisest thing for me to do is to marry Ernest. I am very fond of him and he is kind which will be a contrast … I can’t go wandering the rest of my life and I really feel so tired of fighting the world alone and with no money. Also 32 doesn’t seem so young when you see all the youthful faces one has to compete against. So I shall settle down to a fairly comfortable old age.’ After her peripatetic childhood, and abusive marriage to Win, Ernest represented financial and emotional stability, comfort and respectability. Wallis worried briefly that his wholesome ponderousness was the polar opposite to her Southern emotionalism. She was fun, spontaneous and extravagant. He was methodical and cautious. Later, he was dismissed amid the upper-class circles into which the Simpsons were propelled as ‘crashingly middle class’ and a bore.

Ernest was transferred to run the British offices of his shipping firm, and in May 1928, Wallis followed him to London. They married on 21 July at Chelsea Register Office. Wallis wore a yellow dress and blue coat that she had bought in Paris the previous summer. Although they considered the clinical nature of the register office ceremony ‘a cold little job’, she found their honeymoon ‘a blissful experience’. Driving through France, Wallis discovered that her husband was cultured, considerate and spoke French fluently. Ernest may not have been the most exciting or diverting company but he was a thoroughly decent gentleman. His great-nephew, Alex Kerr-Smiley, remembers: ‘Ernest was just a nice person. He was an extremely nice uncle. He was almost like our fairy godfather.’

After the harrowing uncertainties of the previous decade, Wallis, aged thirty-two, could finally relax. Looking forward to a new life in London, she ‘felt a security that I had never really experienced since early childhood’. Her domestic equilibrium was to prove short-lived. Three years later, the dull conformity of her marriage was shattered by the arrival in their steady realm of the dazzling Prince of Wales.

* Fulco di Verdura was an influential Italian jeweller who designed for the duchess. His career took off when he was introduced to Coco Chanel by Cole Porter.

† The Mason–Dixon line was the American Civil War partition between the slave states of the South and free states of the North.