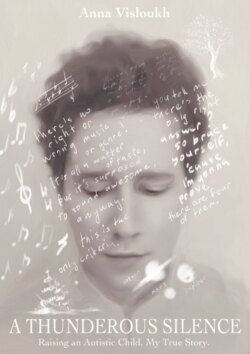

Читать книгу A Thunderous Silence. Raising an Autistic child. My True Story - Anna Visloukh - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

4. I Am Saved by the Cross, But It Gets Too Heavy to Carry

ОглавлениеThe paperwork I was given in the clinic has now swollen to gigantic proportions and no longer fits in my handbag. I am holding the medical records in one hand, and my child’s hand in the other.

I am walking down the street crying my eyes out. I take no notice of passers-by, weeping without wiping away my tears. My frightened son clutches at my hand as he drags his feet silently beside me. Passers-by do look at me, and some even ask me what is wrong, but I only see them through frosted glass and hear nothing. All I want is to be invisible for the rest of time, so I will no longer have to deal with that indifferent doctor who fills out Tim’s medical records without any signs of hope, with sleepless nights, with mountains of drugs, with the pity of my friends who keep asking me how I am doing.

No more burning tiredness and fatigue in my soul… and not him around me, either? He is walking close beside me. His straw-colored curly hair bounces every time I tug his hand, «Can’t you walk any faster?» But he never answers. Yes, he will stay. Will he stay there on his own, without me? What would he do without me? Who else would look after him? Stop.

I freeze in the middle of the sidewalk. He slows down and timidly raises his eyes to me as if saying, «Mommy, please don’t cry.» I stay silent, thinking to myself, «Lord, why did you give me such a cross to bear?»

«Mommy, please don’t cry.»

I feel as if I were awoken from a pointless sticky dream and start looking around. The everyday bustle of the city continues around us as we stand on the edge of the sidewalk, and suddenly I come to understand that this is my life and I need to deal with it. I must live a life, not drag on with bearing a heavy cross ruefully. The next minute I lift my eyes and see the cross. We are standing next to a cathedral. Something clicks in my head. I grab my son’s hand again and rush through the gates to the cathedral yard where I see the dark silhouette of a priest.

«Father,» I say breathing heavily. «Father, I want to baptize my boy! When can it be arranged?»

He turns around. He is young, dark-haired, and he replies loudly in a cheerful voice, «You can do it right away! I am about to do a christening!»

«But I have not got any baptismal cross or towels, and there are no godparents with me.»

«Don’t worry about any of that, just come on in,» he says, pushing us inside impatiently. «Everything will be all right!»

We all come inside. It is a small baptismal church in the cathedral courtyard, and people are already waiting for the priest there: a young couple with a baby in their arms, a woman with a girl, a teenager and a young woman in a headscarf.

«You can buy a baptismal cross, a candle and a towel in the church shop,» the priest tells me as he hurries towards the ambon.

«Of course, I will do it straight away,» I reply, frantically rummaging in my purse to make sure that I have enough money, hoping there is enough money to make a donation to the church afterwards. «But we have no godparents.»

«Just give me the name of the person that you want to be his godmother,» the priest says, and then he turns towards us and begins to read out a prayer.

I look at my son. He is standing there with a candle in his hand, looking serious and suddenly all grown up.

It’s all coming back to me now.

It was a summer day in July. It was a clear day, full of the concentrated aromas, the loud sounds and the colors of a Ukrainian village. I was seven years old.

«Grandma Ganu, grandma Ganu!» a neighbor shouted in what was clearly a belligerent tone.

Grandmother slowly straightened up, wiping her wet hands on the apron that she had put on to prepare the food for the piglet.

«What do you want, Rosa?»

«Your bloody chickens are in my garden again. Do something about it.»

«Oh, for heaven’s sake!» My grandmother quickly grabbed a stick and drove the silly chickens with their useless wings safely back to their own territory. Aunt Rosa’s husband, grandfather Shicka, arrived on the porch. He made funny penny whistles for us that would show a long rubber tongue if you blew into them. I had a collection of his whistles. This time the old man gave me a new whistle and a bowl of white currants he just put it my lap.

A large saucepan of water was boiling over the stove in our house. Grandma was going to give me a bath, and worst of all, wash my hair. The next day we expected a visit from the local priest (I didn’t know who he was, but I was already afraid in advance!). I was going to be baptized.

In the morning I was dressed up in a new gown, and my freshly washed hair was tied up with the bow I hated. The battle with my grandmother to wash my hair had been horrendous, but Grandma had won. She was a Polish noblewoman, after all! When my hair was tied back against my will, they made me sit on a bench inside the house. My deaf-and-dumb aunt Lisa sat next to me, but Grandma looked out of the window impatiently.

Only my elder sister, who was seventeen, chuckled in contempt, took a book and pointedly went out to the garden. She knew that my grandmother would have me christened against my parents’ wishes, even though my father was an army officer and a committed Communist. That was to be done secretly, that is why Grandma invited the priest to her house. I had no idea what was going to happen to me, but I tried to be brave and use all of my strength not to go into tears: I was not a baby any more, I was going to start school in September.

My parents had sent my sister and me to stay with our grandmother for the summer, to relax in the village and live on healthy country food. In the community area of the military camp where we lived then there was no access to natural milk or fruits.

Finally, the door opened, and a man with shaggy hair, dressed in a long black robe walked in. He spoke in a stately voice, «Blessings to this house. Bless you all.»

My grandmother and aunty rushed over to this large man and for some reason began to kiss his hand. I went cold, fearing that they would make me do the same. I thought to myself: that’s why they had dressed me up, just to kiss this big man’s hand, and if I did not, he would snatch me and put me into his big suitcase and drag me off to his «church’ that my grandmother always used to talk about.

I was petrified at the thought and tried to press myself deeper into the corner of the room in the hope that he wouldn’t notice me. No chance! The big man suddenly pointed at me with a thick finger, and laughed out loud.

Then he opened his case and began to take out some strange looking items: a long gold-colored tablecloth with a hole in the middle that he put around his neck, some gold-colored sleeves and other items I had no clue about. I closed my eyes in horror. Just before I was about to forget my pride and scream out loud, something warm and fragrant touched my head.

«The bow on your head is very pretty,» I heard suddenly and opened one eye. Someone stared at me closely, so that I could see the black pupils in his eyes and the red little sunshines around the pupils that radiated kindness. The man with the kind eyes patted my head again and chanted something long and reassuring. And so I was baptized.

«Next time I will give her communion, bring her to the church,» the wondrous man told my grandmother in his low voice before taking his leave.

My grandmother hurriedly crossed herself, and I ran out into the garden. I was bursting with some unfamiliar feeling and just wanted to share everything that had happened to me with my sister, to show her my beautiful cross. I ran over to her pulling the cross from under my dress and cried out, «Look what I’ve got!»

My sister reluctantly looked up from her book, glanced at the marvel that I was holding out in front of her, and hissed though clenched teeth, «Put that away you fool, and don’t show it to anybody else.»

I felt shocked. I stumbled and took a step back trying not to fall, and felt someone catch me: it was Grandma. I buried my face in her apron and cried for the first time on that day.

My mind returns to the present moment only when the priest touches my arm.

«What is the name of your son’s godmother?» he patiently repeats.

«Ah! Her name is Lydia.»

In my mind I ask my best friend if she agrees to be godmother to my son and at the same time I apologize for not asking her in the first place. Somehow I am sure that she will not have turned me down.

My son clumsily crosses himself, but he bows down gracefully, carefully holding the candle in his small hand. I am standing there looking at the pale gentle candle flame. It brings back memories.

On Sunday, very early in the morning, there was a Ukrainian market in our big ancient village that the old timers preferred to describe as a small town. It was loud and colorful; it was a genius’ inimitable masterpiece, with rapidly changing patterns like in a child’s kaleidoscope.

We lived in the heart of the village on the hill. Grandma’s garden went all the way down to the river, and the large marketplace across the river could be seen from our house. The river had the wonderful name of Rostavitsa. It was wide near the old watermill, but then surrounded the village like a silvery belt and in some places became little more than a creek.

A solid stone bridge stretched over the river, and carts drove rumbling over it early in the morning to get to the market. It was so pleasant to sleep to the sound of their incessant noise. During the night Grandmother would fry fish in the oven and bake biscuits and buns that she would sell to hungry villagers from afar.

At dawn, when the sun had just started raxing and showing from under its cloudy wrapper, Grandmother would gather up everything she had prepared into a bundle and head off to the market. I would carry on sleeping, and after I woke up, I would splash my face with cold water, lock up the cottage, and run off into my dreamland.

It was a fabulous place: they sold sparkling transparent sticks of candy formed as roosters there; cute little lilac-colored piglets lay there grunting, and a speckled guinea fowl huddled in the sack looked at you with its angry round eye. Purple horses shook their coal-black manes, and the whole place smelled of thyme and mint, of dill and half-sour pickles.

The counters were crammed with rich and juicy tomatoes, bottles of homebrew and ruby colored cherry brandy, samples of which were generously given away, with homemade shoes and beautifully crafted clothing. In the center of the market there was blind Old Sashko sitting, playing the accordion and singing the song about tankmen.

The day before my sister had left for Kiev. She was bored with the village life. Her cousins were in college, their holidays had not yet started, and Grandma did not let her to go to dances on her own as my sister was a city girl and someone could have hurt her. She persuaded Grandmother to let her go with a neighbor, Aunt Rosa, to Kiev to meet their niece Larisa who was to arrive from Moscow. Soon the cousins would come for the summer break, so it would be more fun. Back in those days there was hardly any entertainment in the village, just a club and a teahouse on the hill near the village shop.

This day was like any other market day. The night before my grandmother had fired the furnace, kneaded the dough and cleaned fish, and I had fallen fast asleep after playing with local girls in the creek. Through my slumber I heard the clatter of horses and carts on the stone-paved road. So, for sure, the market would be open in the morning!

I woke up abruptly, as if someone had struck me. The sun was fully up, and my grandmother’s favorite mallows bashed against the window shaking their heads reproachfully as if to say, «You have overslept, sleepy head!» «No, no, I still have plenty of time! All I need to do is get dressed.»

I opened my bedroom door to the living room and recoiled in terror. The living room was no longer there. My grandmother’s favorite room, familiar and loved to the finest detail, was gone. The table with the wooden benches was gone. Even my grandmother’s wooden chest was gone along with the icon case in the corner of the room. There was only foul-smelling grey smoke shaggy like a monster.

I slammed the door in horror and screamed out loud. I ran around my little room wondering what to do. There was a tiny window in there that I had never opened. There was nobody around to hear me. The little window overlooked the garden, and there were no neighbors around, and even if there were, on that day they were probably already at the market.

I went back to the door, opened it, and suddenly made a decision. Remembering the voice of the wondrous man that had put the baptismal cross on me, I whispered to myself, «God bless my soul». I squeezed the cross in my hand and plunged through the smoke.

I made my way through the dense fumes, with my mouth tightly closed, hardly breathing. The fire in the kitchen stretched out its long paws aspiring to grab me by the hair. I tried not to look at it. I fell to my hands and knees and felt my way to the door. Struggling, I pushed it open, and literally fell out into the hallway, slamming the door behind me.

For a while I lay on the cool dirt floor, gasping and coughing from the thick acrid smoke. I felt as if I were coughing the smoke out of my lungs. I lay there until my throat cleared, and then I stood up and tried to push the front door open. The door did not budge. I pushed it harder with all my strength, again and again, and then, crying and smudging the soot on my cheeks, I finally realized that the door was locked from the outside. For some reason, this time Grandma had locked me in. I slipped to the floor and prepared to die.

I do not know how long I sat there, but probably it was not very long. Suddenly the door was kicked wide open, and I fell out into the street. My elder cousin, Aunt Lisa’s son, was leaning over me. I found out later that walking past our house one of our relatives had seen dense black smoke coming from the windows. He rushed to the market to find my grandmother. She gave the house keys to my cousin who had been helping her out at the market, and hurried along behind him as fast as she could, with her heart filled with fear. I only vaguely remember what happened next. All I remember is being forced to drink some warm liquid until I threw up.

The smoke from the building dissipated, but the floor by the stove was burnt through: when Grandma went to the market, she had closed the shutters too early. After a couple of days, only the blackened beams in the rooms reminded us of what had happened.

My mother arrived and cried for a long time, cursing in Polish and then in Russian, trying to whitewash the terrible ceilings. At the same time my grandmother prayed guiltily in front of her icon in the corner, whispering, «Thank you for saving us, God.»

The priest asks us all to face the west and renounce the devil. Then he begins to read out a beautiful prayer. Later I will learn that it is called «Creed», the symbol of faith.

After that he plunges my son and another child into the baptismal font, sprinkles holy water on the adults’ heads and puts crosses around everyone’s necks. Finally, all the people who have just been baptized walk around the baptismal font in a procession holding candles in their hands. On the last lap the candle in my son’s hand shakes and goes out. I cannot help but cry out. The priest gives me a stern look, as if to say «be quiet», and he leads the boys to the altar. That is the end of the christening ceremony.

«Father,» I say rushing over to the priest. «My son’s candle went out. What does that mean?»

«What are you talking about?» he asks me calmly, as he removes his beautiful vestments; now I know it’s not a tablecloth but an orarion. «It means that you need to go to church more often, my dear, and then you will no longer ask such ridiculous questions. You’ll learn to cross yourself properly, too.»

I fall into an awkward silence. Really, God knows the kind of ridiculous thoughts that have come into my head. It was most likely just the wind from the window that blew the candle out.

I go off to find my child.

«What are you doing, my son?»

My son is standing before the altar, fascinated by the icon of Virgin Mary, Mother of God, and he does not seem to hear when I’m calling him. Reluctantly, he turns round to face me. «Mommy, is it all right if I stay here to live?»

So we have stayed there to live, and church has become part of our lives. From that day on we have been welcome in God’s house that is open to all. Its doors are open for everyone, but not everyone’s willing to enter. We, too, have not come in further yet than only just passed through the doorway.