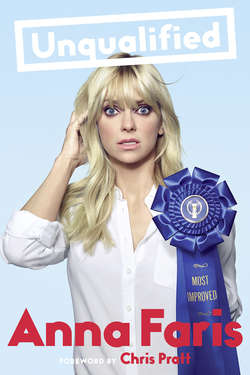

Читать книгу Unqualified - Anna Faris, Anna Faris - Страница 7

ОглавлениеIntroduction

I Rote a Book!

I’m not qualified to write a book.

I might as well have woken up one morning and thought, What can I do today that I have no experience doing, that I’m sure to make an ass out of myself while doing, and that will test a population’s patience with my mental ability? Rite a book! So I called my agent and got a book deal. Bingo, bango! Anyone can do this!

Truthfully, though, I’m terrified. I should have done a better job of thinking this through. You know how the biggest decisions in your life never appear as the lightbulb flashes you see in cartoons but instead germinate in the deepest crevasse in your brain and slowly take root until suddenly a blossom emerges in the forefront? That’s pretty much what writing a book was for me. An idea I toyed with now and then, which eventually became more now than then, and suddenly I was pursuing literary agents and, before I had a chance to come to my senses, I was documenting my life (or at least my life in relationships) in writing.

As my mom keeps reminding me, I do have a degree in English from the University of Washington, a school that after five long, hard years taught me that I am unpleasant to be around after smoking weed out of a four-foot bong. But I don’t think anyone, in my seventeen years of living in Hollywood, has ever actually asked me about my education. That’s kind of the beauty (or horror?) of LA. No one gives a shit about any credit outside “the industry.” So writing a book seemed like a fun, exploratory journey into the literary world, and a nice way to flex those English-major muscles.

But now the train has left the station and I feel as though I’m bound to disappoint many people in my life, including you, dear reader. I’m an actor, and have been since I was nine, so I should point out that I have been hiding behind characters and other people’s words for a long time. There is always an out. Writing a book and putting my own words into the world is terrifying in the very way that performing in front of a camera will never be. In 2011, I naively and arrogantly agreed to be the subject of a profile in the New Yorker. It was written over the course of six months and when the fact-checker called me a few weeks before publication to read my own words back to me—words that I had spoken and completely forgotten—I knew I had to leave the country for good. My own vanity was about to destroy all I had worked for in Hollywood. Ultimately that didn’t happen, but I did have to make a couple of apologetic phone calls.

Other small points of concern: I haven’t used a computer properly ever, in my entire life. When you have a job where you make faces and say other people’s words, you don’t have to learn technology. Sometimes you don’t even have to learn how to dress yourself, ’cause nice Lara is there to zip you up. So anyone at your neighborhood nursing home is more qualified to be punching these little buttons on this here keypad.

In fact, I think I might even have a typo in the title of this chapter.

Also, I don’t know why I can’t nap. I know that’s not related, but it sort of is in that I want you to know everything about me, dear reader. You and I will be best friends after all this is over. I would like it if you would send me your autobiography, too.

Oh, and I’m really bad at social media. Why do I need to record everything online? Can’t I just keep it in my brain? But I’m told that it’s necessary to sell a book these days.

So, just so we understand each other, I don’t know what the fuck I’m doing.

That’s never stopped me before, though. Actually, that’s not true. Until I was nineteen, I thought I was supposed to know everything. I didn’t, obviously, but I accepted that there was a universal understanding that we all faked it, and the polite thing to do was quietly continue the charade. I knew to lay low and keep quiet so I wouldn’t get made fun of. Then one day during my sophomore year at UW, I was sitting in the back of Intro to Something (Psychology? Sociology? I can’t remember. I was miserable at the beginning of college. I sat in the back of giant lecture halls writing letters to Dustin, the “just a friend” I was in love with, who was studying abroad in Spain), when this good-looking fraternity guy raised his hand. I don’t know what the professor was even talking about, just that the dude with his hand up said, “I don’t know what that means.” I remember a record scratch in my head: Somebody just confessed they didn’t know something? There was so much bluster—everyone was always pretending they had all the answers. So it came as a shock to me that it was okay for someone—especially a hot frat type—to say, “Yeah, I don’t know what you’re talking about. Maybe you’re all going to think I’m stupid, and maybe I am, but I don’t understand.”

There’s liberation in admitting you don’t know what you’re doing. For me, it took years of comedy acting to get there. When you’re shooting a film like Scary Movie you have to constantly confess that you have no idea if something is going to work, and it turns out it feels good to say, “I don’t know how to do this.”

So let me say it again: I have zero qualifications, and no one should be listening to me.

And yet, I want to help you with your love life. I do. I have advice to share—who you should date, who you absolutely shouldn’t—and some cautionary tales, too. Plus, I’m fascinated by other people’s relationships. In fact, I’m fascinated by other people’s lives. What they ate for dinner, who they slept with last night; it’s all equally interesting to me. And while I don’t like to butt in, I do love to offer helpful, if sometimes unsolicited, wisdom. (That’s butting in, isn’t it? I’m the worst. I’m a horrible person.)

I’ve been doling out romantic advice my whole life. Most recently, and most publicly, on Anna Faris Is Unqualified, the podcast I cohost with my friend Sim Sarna, but my penchant for digging into other people’s personal lives started decades ago. When I was eleven, my mom’s friend came over to our house, sobbing. She was ranting about how awful her husband was, and I eavesdropped until I couldn’t stand it anymore. “You have to leave him!” I butted in. She had two kids, but who cared? Kids, shmids. I was passionate about this. It was the only logical solution. She could run away and start a new life! She should totally leave him! Why didn’t she just leave him?! It would be so easy! JUST LEAVE HIM!! When she didn’t—because, of course she didn’t, because life is complicated—I was profoundly disappointed.

My craving for a relationship of my own started before I played therapist to my mother’s friend. For as long as I can remember, I wanted a boyfriend so, so badly. My mother, a ferocious feminist, couldn’t stand how boy crazy I was. She hated Pretty Woman and didn’t let me watch Grease because she disapproved of how Sandy changed herself for Danny in the end. She was adamant that I never be dependent on a man, and it created a massive inner conflict in me. I knew I wasn’t supposed to long for a boyfriend as much as I did, which just made me want one more. I’d stay up late reading Sweet Valley High books, and even though I knew they were kind of stupid, I got off on the drama. The idea of boys fighting over me made me dizzy, probably because no one ever did. I bribed Jason Sprott, the fastest boy in the third grade, with ice cream just to get him to talk to me.

In the absence of a relationship of my own, I lived through other people’s. I read Dear Abby and listened to Dr. Joyce Brothers and watched Sally Jesse Raphael. I did theater work around Seattle and was riveted when the lead actress flirted with the hot set dude. I wanted so intensely to be grown up, because to me, the defining feature of adulthood was getting to be in love.

When I was seventeen, I started dating my first official boyfriend, Chad Burke. He was unbelievably good-looking, but also, shall we say, “dark.” Chad was popular, thanks to his looks, but he was also cynical and angry and would sneak out at night to write Rage Against the Machine lyrics on the telephone poles in our town. I couldn’t believe that someone that hot would like me, and I was young, so I would have done anything for him. We went out for a year, and, like Felicity, I followed him to college. Two weeks after the school year began I would call his fraternity and he wouldn’t come to the phone. I got drunk and went to his frat house and they wouldn’t let me see him. Eventually we ran into each other and Chad told me he was dumping me. Clearly, I didn’t have as much of a handle on the whole dating thing as I thought I did.

After Chad, I went from one relationship to the next. Because I was constantly trying to make a bad thing work, I was a serial monogamist, and I’m embarrassed to admit that it used to take meeting another person for me to realize that Oh, this relationship might not be working. I’ve had my share of romantic troubles, and what has continually provided me with comfort is the knowledge that millions of people out there have been through what I’ve been through. Heartbreak and rejection are communal. Love is life’s greatest mystery and wildest adventure.

God, that’s so fucking corny.

I started a relationship podcast because, to me, giving advice and hearing other people’s stories is better than therapy. Not that I’m in therapy. I probably should be, but I find it too frustrating to not know anything about the person I’m talking to. The two times I visited a therapist I found myself asking about them—“I don’t see a ring on your finger. Are you divorced? That must have been hard. Tell me everything!”—and they politely but firmly deflect and steer the conversation back to me. Then I try to get them to tell me about their other patients, which they seem to think is against some sort of rule.

Hearing other people’s problems is, in its own weird way, comforting. It’s a relief to me that so many of the trials I’ve had, other people have, too. And while I may be unqualified, I’m not uninterested. I care and I listen and maybe I don’t always give the best advice, but I really do try. I dig a lot. I have no problem asking anyone anything. I’ll try to curb my own obnoxiousness by saying, “I know this is personal … ,” but then I go in for the kill: “How did you and your husband meet?” or “Oh, you’re online dating? How does that work? Ever get catfished?” Some people really respond to it. Other people really, really don’t.

I know what you’re thinking: That all sounds great for a podcast, where that girl who looks like Mena Suvari can take callers and have a conversation, but what’s going on with this book? Well, apparently, after two years of hearing other people’s stories, I’ve learned a few things. About myself, about dating, and about the commonality of lust and heartbreak and desire and rejection and giddiness. I’ve been reminded that whether you’re in LA or Atlanta or Dubuque, your pride will be wounded after a breakup, you’ll struggle to tell a friend when you can’t stand her boyfriend, and when you’re truly happy, you’ll know it. I’ve learned that there are some universal truths: If your closest friends stop showing up to your barbecues, you’re probably in a bad relationship. And if you opt for kindness over teasing, you’re probably in a good one.

I’ve come a long way since that night in 1987 when I so cavalierly told a mom of two to up and leave her husband. I don’t get a rush from encouraging breakups anymore. These days I’m more interested in bringing people together. In fact, just recently, a friend of mine was going through a bad breakup, and thank God I was there. She and her ex had had this incredibly passionate, whirlwind courtship—within two months of meeting they were planning the wedding. But then they broke up, which was not entirely surprising in a situation like that. Shortly afterward, my friend came over to my house and was so incredibly upset. The more I thought about it, the more I knew I had to intervene. There was still a lot of love there, I just knew it, so I asked my friend for her phone. “What are you going to say?” she asked.

Didn’t she trust me?

“Just let me have your phone,” I said. My text was simple: “Hey, it’s Anna. I don’t know what you’re doing right now but will you come over?” He did, and they had a beautiful, romantic night. I was so proud of myself! I got them back together and all would be fine and, like I said, I knew there was love there. I knew it.

He ended up leaving two days later and she was devastated and I think maybe a little annoyed at me. So, yeah. It backfired.

Still, points for trying?

In this book, you’ll find stories of my relationships, both the disastrous and the heartwarming. You’ll meet childhood Anna (pronounced Ah-na, rhymes with Donna, even though everyone gets it wrong and I never correct them), armed with flannel shirts and menacing headgear, and adult Anna, with more flannel shirts but much better teeth. You’ll get some advice, a few lists, and some childhood photos (I’m the short one).

Read. Have fun. And please purchase the sequel: I Have No Idea What the Fuck I’m Talking About: The Motherhood Book.