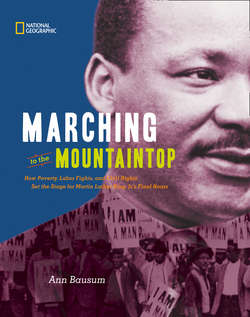

Читать книгу Marching to the Mountaintop: How Poverty, Labor Fights and Civil Rights Set the Stage for Martin Luther King Jr's Final Hours - Ann Bausum, Ann Bausum - Страница 9

INTRODUCTION

“Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen, Nobody knows my sorrow. Nobody knows the trouble I’ve seen. Glory, hallelujah!”

ОглавлениеChorus from a freedom song based on an African-American spiritual

As I remember it, the chore of taking out the trash fell to me every week of my childhood. My family might disagree, but if anything could trick my memory into believing this statistic it is my recollection of the garbage itself. Pungent. Disgusting. Foul. Unforgettable.

Back then, garbage was truly garbage. To take out the trash during the 1960s meant to get up close and personal with a week’s worth of refuse in the most intimate and repulsive of ways. No one had yet invented plastic garbage-can liners or the wheeled trash cans we have today. At that time our family’s garbage went into aluminum cans with clanging metal lids. And the garbage went in naked.

In 1968, when I was ten years old, people really cooked. Recipes started with raw ingredients, and the garbage can told the tales of the week’s menu. Onion skins, carrot peelings, and apple cores. The grease from the morning’s bacon. Half-eaten food scraped from plates in the evening. The wet, smelly, slippery bones of the chicken carcass that had been boiled for soup stock. Mold-fuzzy bread. Spoiled fruit. Slimy potato peels. Scum-coated eggshells. Then add yesterday’s newspapers. Used Kleenex. Cat-food cans lined with sticky juices. Everything went into the same metal can out the back door of our home in Virginia.

The story of our garbage multiplied itself to infinity at homes throughout the nation. In communities where temperatures soared, garbage baked in the summer heat like some witch’s stew until foul odors broadcast its location, flies bred on the vapors, and maggots hatched in the waste. Wet, raw, saturated with rancid smells that lingered long after the diesel-powered truck had lumbered away: That was the garbage of the 1960s. The people who collected the trash were always male, and we called them, simply, garbagemen.

It’s universal: Young people take out the trash everywhere, including in Memphis during the 1968 strike.

This book is about the story of garbage in one city—Memphis, Tennessee—and the lives of the men tasked with collecting it during 1968. These men, all of whom were African American, labored brutally hard for such meager wages that many of them qualified for welfare. Six days a week they followed their noses to garbage cans (curbside trash collection had yet to become the norm); then they manhandled the waste to the street using giant washtubs. The city-supplied tubs corroded with time, leaving their bottoms so peppered with holes that garbage slop dripped onto the bodies and clothes of the city’s garbagemen as they labored.

During the 1960s the sanitation workers of Memphis showed up for work every day knowing they would be treated like garbage. By the end of the day they smelled and felt like garbage, too. Unfairness guided their employment, and racism ruled their workdays. So passed the lives of the garbagemen of Memphis until something snapped, one day in February 1968, and the men collectively declared, “Enough is enough.” Accumulated injustices, compounded by an unexpected tragedy, fueled their determination. Just like that they went out on strike, setting in motion a series of events that would transform their lives, upend the city of Memphis, and lead to the death of the nation’s most notable — and perhaps most hated — advocate for civil rights.

Labor relations, human dignity, and a test of stubborn wills drove developments that spring in Memphis, Tennessee. Behind this union of worker rights and civil rights stood the men expected to handle one ever present substance: garbage.