Читать книгу Susanna Moodie - Anne Cimon - Страница 15

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2 Bluestocking

I have been one of Fancy’s spoiled and wayward children… I have studied no other volume than Nature, have followed no other dictates but those of my own heart, and at the age of womanhood I find myself totally unfitted to mingle with the world.

– Susanna Moodie, Letters of a Lifetime

After Thomas Strickland’s death, Reydon Hall remained the family home, but barely. The servants were let go, the ornate carriage sold, and a general air of decay infiltrated the scantily furnished rooms, the unused attics, the empty barns and stables.

Portrait of Catharine by Cheesman.

Catharine was only a year older than Susanna and was her

“dear and faithful friend.” She married and emigrated

to Canada the same year as Susanna did.

Weakened by her grief over the loss of her father and sensitive to the dampness and mould in the house, Susanna fell ill with whooping cough and became so thin she wrote to a friend that she looked like a “perfect skeleton.” The usual medical recommendation at that time was “a change of air.” But how could Susanna go anywhere when there wasn’t even enough money to buy clothing?

Aunt Rebecca, who lived in London’s Bloomsbury district, came to the rescue. She invited Susanna, and her sister’s, to stay with her. Aunt Rebecca was a second cousin to their father, and a wealthy widow. She had been married to the architect Thomas Leverton, who had designed the fashionable Bedford Square where Aunt Rebecca lived.

At sixteen, Susanna liked to mingle with and pour cups of tea for the literary women known as “bluestockings” who often gathered in Aunt Rebeccas living room to discuss the latest books.

In 1826, Susanna stayed for several months at another London address, on Newman Street. Her sixty-year-old cousin, Thomas Cheesman, asked her to be a companion to his niece, Eliza. Cheesman was a sort of Renaissance man and amateur artist who became a father figure to her. He encouraged Susanna, and also Catharine, when she visited, to write.

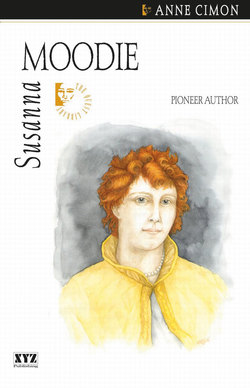

One afternoon, Cheesman, or Cousin Tom, as the family called him, stared at Susanna as she entered his studio, where paper and paint cluttered the table, and the raw smell of turpentine filled the air. He remarked:

“You look particularly fetching, today, dear. Sit down. I would like to do your portrait. I must capture those red curls for posterity.”

Susanna couldn’t refuse. In fact, she did feel pretty in her new yellow jacket with its rolled collar and the string of pearls around her neck. She had even clipped a yellow ribbon in her auburn hair.

As she sat for the miniature oil portrait, Susanna was thinking, as she often did then: If only my father were still alive. I miss him so.

When Cousin Tom allowed her to look at the portrait, Susanna felt surprised at how he had been able to capture the sadness and apprehension that she tried to hide from everyone.

Back in Suffolk, Susanna continued to recover from her illness. She loved to ramble in the countryside, away from Reydon Hall. She now knew that she preferred the country to the city. She sought inspiration for poems in nature. Her favourite outing was to the North Sea where the salt air cleansed her lungs and cleared her thoughts. Her appetite had returned as a result of her long walks.

One afternoon she relaxed on the beach, her picnic basket empty except for the remains of her lunch of apples, cheese, and bread. She recited out loud to the gulls swooping overhead her favourite verses from the book everyone raved about, Byron’s Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage:

Are not the mountains, waves, and skies, a part

Of me and of my soul, as I of them?

Is not the love of these deep in my heart

With a pure passion? should I not contemn

All objects, if compared with these? and stem

A tide of suffering, rather than forego

Such feelings for the hard and worldly phlegm,

Of those whose eyes are only turned below,

Gazing upon the ground, with thoughts which

dare not glow?

Susanna wanted to be one of those people whose thoughts dared to glow, and she hoped, as the waves curled and broke on the pebbly beach, that she would meet a man as passionate and soulful as Lord Byron, a man she could share all of herself with, someone who would travel the world with her.

Susanna overcame her isolation not only by reading her favourite authors such as William Wordsworth, Robert Burns, Sir Walter Scott, and William Cowper, but by immersing herself in an exchange of letters with her new literary friends. One of her most important correspondents was a local man named James Bird, known as the Bard of Yoxford.

One morning, before her walk, Susanna sat at her desk in her bedroom and pondered how to respond to the verses Bird had sent her for criticism. She didn’t like their style. How could she express her true opinion without hurting Bird’s feelings? Soon her pen was scratching onto the blank sheet of paper her candid answer:

“You are most happy in your descriptive scenes and I care not for Story in a Poem. I know most of Scott’s descriptive scenes by heart while I scarcely remember his stories… Descriptive poetry often goes so home to my heart that I cannot read a beautiful drawn scene of this kind without weeping.”

Susanna’s high spirits came through. Tongue-in-cheek, she wrote,

“Mama is busy gardening and more interested in housing her potatoes for the winter than the blue stocking fraternity in composing sublime odes or entering the joys or sorrows of some imaginary heroine…”

Being a heroine was the goal of Susanna’s elder sister Agnes. Upon the death of Queen Charlotte, wife of King George III, Agnes had written a eulogy that was published in a London newspaper, and this immediately had opened doors into the aristocracy for her. Agnes often stayed at Aunt Rebeccas house but didn’t think it was grand enough, according to Susanna. Her sister was theatrical and imperious by nature, and cared too much about her appearance.

The two rival sister’s often visited friends together. Susanna, unlike Agnes, never put on airs, and joked about their being “poor poets.” They even had to borrow the neighbours donkey to pull their chaise, for they didn’t have any other way to travel.

On one memorable evening, Susanna and Agnes returned from visiting the Birds in the village of Yoxford, about an hour away from Reydon Hall. The night was clear and the stars twinkled as the donkey, which Susanna affectionately referred to as “our mouse-coloured Pegasus,” plodded down the road.

Susanna pulled her cloak tighter and squeezed close to Agnes. They were both silent, Susanna lost in thoughts about Samuel, their younger brother, who had recently emigrated to Upper Canada. A friend of the family had talked the destitute twenty-year-old boy into trying his hand at farming. Samuel’s letters were filled with marvellous descriptions of the wilderness and exotic place names such as the Otonabee River.

“Agnes, do you ever long to join Samuel in Upper Canada?” Susanna asked, breaking the silence of the night. “It seems like such a romantic place.”

Susanna didn’t have to wait long for an answer as she felt her sister stiffen beside her on the seat.

“O no, never,” Agnes blurted. “I only dream of living in London.”

As their chaise pulled in at the tollgate, clouds suddenly formed and the air turned cold. In the semi-darkness, Susanna spotted a vagrant man who was hiding behind some bushes. Suddenly the man let out an unearthly scream.

“Someone’s tearing at my veil!” Agnes shrieked as she clutched the flimsy material, though she later admitted she had only imagined this.

Susanna laughed whenever she recounted this nerve-tingling incident, which she wanted to include in a story for a gift-book anthology. She hoped to make her own mark and distinguish herself from her flam-boyant older sister. She was gaining confidence as a professional writer and didn’t like the fact that their shared family name sometimes caused confusion. She wrote to Frederic Shoberl, the editor of the gift-book anthology, Ackermanns Forget-Me-Not, on June 3, 1829, to clarify a matter:

“My sister and I seldom communicate our literary business to each other, as our friends in the world of letters are often of different parties and totally unknown to each other, but I am sure Agnes is too honourable ever to have demanded payment for me, without apprizing me of her intention.”

Catharine was another matter altogether. Susanna had grown so fond of the sister closest to her in age that she remarked in an undated letter to the writer Mary Russell Mitford, that she would prefer giving up her pen rather than “lose the affection of my beloved sister Catharine, who is dearer to me than all the world – my monitress, my dear and faithful friend.” Susanna had sent one of her poems to Mitford, who had responded with compliments. From the Berkshire area, Mitford was sixteen years older than Susanna and had gained critical and popular recognition with her five-volume Our Village, a collection of rural sketches.

For the time being, Susanna busied herself writing and publishing children’s books. These earnings helped their mother make ends meet. She shared with Catharine the friendship of Laura Harral, daughter of Thomas Harral, the editor who published their stories and poems in the gift-book annual, La Belle Assemblee. Susanna received much praise when her story “Old Hannah: or, The Charm” appeared in 1829. In a bold fashion, Susanna sketched a story about the Strickland family’s old and cantankerous servant Hannah, who had entertained her with tales of ghosts and magic since she was a child. The fledgling author had created her first memorable character based on a real person.

In the summer of 1830, Susanna, now twenty-seven years old, lived in London as a guest at the house of Thomas Pringle and his wife Margaret. Susanna had been “adopted” by Thomas Pringle, who edited a popular journal and had published her works. She referred to him often as “Papa” in letters to friends at that time.

As a young man, Pringle had emigrated to South Africa and edited a newspaper for many years until his controversial views against the institution of slavery cost him his livelihood. In 1827, he returned with his family to live in London where he became the Secretary of the Anti-Slavery Society. Aware of Susanna’s compassionate nature and writing ability, Pringle asked her to transcribe, or ghost write, the story of Mary Prince. Prince was a forty-year-old woman born in Bermuda, who had been a slave in the British colony of Antigua and was now sheltered in his house.

Susanna sat on a chair in Thomas Pringle’s study and wrote down the horrifying experiences Mary Prince, who insisted she wanted to stand rather than sit, described in her singsong voice:

“I can show you my scars, Miss Strickland,” Mary offered.

Susanna’s throat clenched. Could she refuse? No. She wanted to see the evidence for herself.

“I’ll help you,” Susanna said, seeing Mary struggle with her blouse.

Susanna stood behind Mary and gingerly lifted the cotton blouse and undergarment.

“Mary, how could they?” Susanna exclaimed, as she stared at the rounded back with its crisscross of embossed black flesh, glistening in the bright light of the lamp on the desk.

“They did that to most of us,” Mary answered matter-of-factly.

Deeply shaken, Susanna sat back down on the chair and continued to record Marys story. Mary had been malnourished, had suffered beatings, and worse, had been raped by her owners, who were supposedly upstanding Britons. How could this be? Susanna now wanted to shape the story into an unforgettable document so that people would learn, as she had, of the evil that was slavery. The pamphlet was published anonymously in 1831, with an introduction by Thomas Pringle, as The History of Mary Prince, a West Indian Slave, as Related by Herself. It sold quickly and was reprinted three times. All the profits went to “Black Mary,” as she was affectionately called by the Pringles.

Susanna also accepted a commission to write the story of Ashton Warner, another former slave befriended by Thomas Pringle. Warner was twenty-four years old, and in such poor health that he died before the pamphlet was even printed.

Susanna’s social conscience was awakened by these dramatic encounters. She resolved that she would no longer be an accomplice to the criminality she had recorded. She poured her outrage into several poems that were published in journals and eventually in her first book, Enthusiasm and other Poems.

That same summer, Susanna met someone else at the Pringles, someone who would change her life forever.

Portrait of Susanna by Cheesman

. In her youth, Susanna’s grey eyes often expressed the sadness

she felt at the sudden death of her father, “a good and just man.”