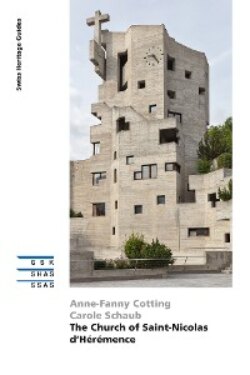

Читать книгу The Church of Saint-Nicolas d’Hérémence - Anne-Fanny Cotting - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe village of Hérémence.

The Dix Valley and its large hydroelectric plants

Life before the dam

Until the first half of the 20th century, the vernacular architecture was a reflection of the difficult living conditions in the valley. The building materials used were the wood and stone found close by, whereas sand, lime and plaster had to be transported from the floor of the Rhone Valley. The houses and other raccards were constructed with the assistance of the community under the directions of carpenters and masons. Before the start of the 20th century, there were no building regulations: each family built as they pleased on the plot of land they owned. Consequently, the buildings were sited haphazardly and movement around the village was especially difficult. The houses were generally limited to two rooms: the kitchen and the common room in which the whole family lived and slept. Keeping the houses sufficiently warm during winter was hard, so the rooms were cramped and the windows small.

Until the 1920s, the only public buildings in Hérémence were the church and the maison bourgeoisiale. The latter accommodated public meetings, votes and club meetings. Its basement housed the prison, a storeroom and the public records. The president of the municipality, the judge and the councillor in charge of the land registry often officiated in their homes and kept official documents there. Schooling, too, was given in private houses until three classrooms were built in 1913. Schooling was made compulsory in 1907 and the school year was adapted to fit in with the villagers’ pastoral and agricultural activities. From a very young age, children – boys and girls alike – took part in their family’s agro-pastoral work and learned all the essential skills: farming, haymaking, animal care, tree-cutting, simple carpentry, etc. It was extremely rare for a young boy to continue his education beyond his compulsory schooling. Even apprenticeship was very uncommon, and the training required to learn a craft was done on the job: “you stole the profession with your eyes”, as a village elder nicely puts it. This situation continued until the 1950s.

The 18th century church damaged by an earthquake in 1946.

The Parish, which corresponds to the municipal district, includes several other small villages: Ayer, Euseigne, Mâche, Prolin, Cerise and Riod. Each has its own chapel and school as, until recently, avalanches and landslides were frequent events and could cut a village off from Hérémence. The church in Hérémence was the centre of the parish’s spiritual life and the place where Sunday mass, fairs, important ceremonies and burials were held.

The first Dixence dam

Construction of the Dixence dam between 1929 and 1935, followed by the Grande-Dixence between 1951 and 1965, profoundly transformed the lives of the valley’s inhabitants. In 1922, the Société Énergie Ouest Suisse (EOS) began its operations in Valais. The company produced electricity, demand for which had grown exponentially since the start of the century following electrification of the towns and cities. Switzerland extensively exploits the hydropower produced by the water of its many glaciers. The Dix Valley was one of the sites that was considered for construction of the first Dixence dam.

The project was very beneficial for the valley. To start with, a motorable road was built from Vex to Motôt, and, from 1932, a regular post-bus service was initiated that facilitated the journeys made by Italian and German seasonal workers. The opening up of the valley and consequent economic income generated by the Chandoline power station led to a first series of important transformations in Hérémence. The municipal authorities set about cleaning up the public roads and the village by convincing the inhabitants to improve or demolish certain buildings, or even to move into new residential zones that had been created on the outskirts. An agricultural district was also established a distance away from the village for reasons of hygiene. Lastly, the village was given a new public building that accommodated the municipal offices and a school that taught home economics.

Construction of the first Dixence dam between 1929 and 1935.

The Grande-Dixence dam

At the end of the Second World War, a new concession was granted for the construction of a second and even larger dam: the Grande-Dixence. The works began in 1951 and continued until 1961, followed by four years of dismantling the installed infrastructure and rehabilitation of the site. The taxes and fees paid by the Grande-Dixence SA company increased in accordance with the greater capacity of the dam, thereby enabling the transformation of the villages in the valley and the clean-up operations to continue. In Hérémence in the 1950s and ‘60s, these benefits were reflected by the construction of a potable water supply network, new roads to the mountain pastures, and a building that housed the primary and secondary school, municipal services, and a central dairy. To create the space required for these constructions, new demolitions were conducted.

The Grande-Dixence dam built between 1951 and 1965 with, in the foreground, the building where the workers lived, affectionately called “the Ritz”.

While the first dam had had a marked impact on the structure of the village, the second would bring fundamental change to Herémensarde society and its way of life. A large proportion of the men living in the Dix Valley went to work on the construction of the concrete giant for periods of varying length. The workers were first accommodated in spartan huts, but these were very soon replaced by a building its occupants affectionately nicknamed “the Ritz”. It could accommodate nearly 450 workers, who benefited from a number of leisure activities such as a football club, a cinema, a library, a gym and brass band concerts, among other things. Such comfort and this choice of entertainments were completely new to these men, who very quickly developed a taste for it. On the site, the youngest workers were encouraged to study apprenticeships, either by correspondence if they remained in Hérémence Valley, or in vocational schools down in the Rhone Valley. For the first time, the men received a regular salary that enabled them to imagine a life different from the one known by their ancestors. Although many families continued to practise farming through attachment to their roots, once the dam had been completed, agropastoralism decreased sharply: in 1940 agriculture employed 76.6% of the municipality’s active population, but only 29.7% in 1960. In order to contain the rural exodus closely associated with new qualifications obtained by men of working age, the municipal authorities promoted the establishment of two factories that could employ them, SODECO and EAB (Elektro-Apparatebau), though the latter had already shut down by 1970. In spite of a diversification of industries and the development of tourism in the neighbouring resort of Thyon, in Hérémence progressive depopulation set in during the 1970s.

For those who remained in Hérémence, their homes underwent a wave of modernisation. The dam worksite had made it possible for young men from the valley to train in all sorts of trades previously unheard of in the region, such as tilers and heating engineers; with regard to building materials, these were easily transported from Sion. Above all, families were now earning money that allowed them to employ these craftsmen to enlarge and install modern comforts in their homes: “In Hérémence before the dam, we could count the number of bathrooms on the fingers of one hand, and then after the dam, the number of houses that didn’t have one”.

View of the valley and village of Hérémence with its church at the centre.

Even today, in spite of the far-reaching hygiene programmes and the transformations made in the houses, the village retains its charm and has a large number of well-conserved vernacular buildings. Visitors to Hérémence are first invited to explore the village’s small alleys and the multi-site museum that includes the crafts museum, a traditional home, the forge, the press and the mill. This visit will demonstrate the extent to which the Hérens Valley has modernised in just a few decades, and the visionary character of the inhabitants of Hérémence and its priest who, when choosing a new church, championed a design as avant-garde as that of Walter Maria Förderer.