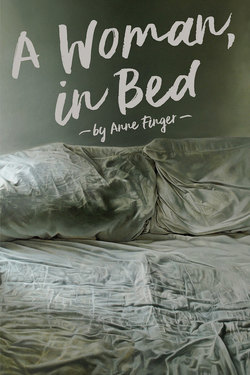

Читать книгу A Woman, In Bed - Anne Finger - Страница 33

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTrain

Jacques and Simone went to the station together. Jacques’ train was scheduled to leave before hers. On the platform, his stern masculine index finger chucked her under the chin, “Come now, come now, it’s not so bad as all that, we’ll see each other again.”

“When?” She regretted the word before it was out of her mouth, but it had issued forth from her body like a rude, unstoppable noise.

“Ah, Simone!” Jacques said, making a quarter turn away from her. She had no doubt that he said, “Ah, Sala!” in just this same tone of voice. I’m like Odette, she thought, with her arms stretched out, her plaintive “Mama, Mama.” Nonetheless, tears spilled out of her eyes and down her cheeks. She bent her head down, wiping her face with four flat fingers.

“Wait a minute.” He walked away, peering at the fine print of the schedule hung on the wall. He laid a hand on her shoulder, “Let me see if I can change my ticket. There’s another train, in an hour.” He spoke with the station agent, passed some extra francs through the opening at the bottom of the grille—she knew how carefully he shepherded every sou—sent a telegram, no doubt to Sala, and took her arm, propelling her to a café. “This way, you will leave before me, and it’s always easier to be the one who leaves than the one who gets left behind.”

He was a trifle put out: he had planned on working on the manuscript in his valise during his hours on the train. (She rubbed lard into her hair before plaiting it. Her name was Bomfomtabellilaba, her name was Lalao, her name was Marie, her name was Anisoa…When I arrived at school I realized I should have given myself more than a perfunctory wash: her smell of pig-fat still clung to me.) Of course, he would still have the same number of hours on the train, but by ten in the evening his powers were spent. (In his thirties, he already had the unshakable patterns of a man well into middle-age: I must have black coffee first thing in the morning. I cannot do any real work—work that engages my intellect, that is—unless I have had a solid seven hours of sleep. Aubergines make my liver too heavy, I never eat them. After ten in the evening, I’m good for nothing but idle conversation, detective novels, or sex.)

Jacques had yet to publish his first book—the war, the excursion to Madagascar, the malarial lethargy with which he had returned home, the trials of his marriage to Sala had all served to thwart his literary output. Since he was no longer a young man, he could no longer produce a young man’s text, no rough diamond with brilliance despite its flaws. (His book, which situated itself on the frontier between several genres—it was a memoir, a traveler’s diary, a grammar of the Malagasy language, an anthropological exploration of the poetic jousts which the Madagascar natives practiced, a philosophical critique of the notion of originality—would be published some two years hence to respectful but hardly glowing reviews.) There would also be the necessity of lying to Sala—his telegram had said, “Unavoidably delayed. Back this evening.” In all likelihood there would be a scene, accusations, denials. Nonetheless, he had been moved enough by the girl’s plight that he had undertaken this action.