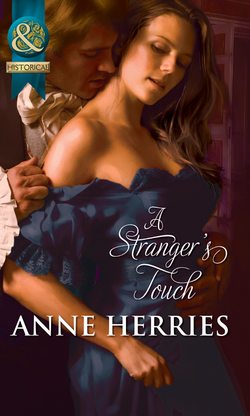

Читать книгу A Stranger's Touch - Anne Herries, Anne Herries - Страница 7

Chapter Two

ОглавлениеMorwenna woke as a hand shook her shoulder. She opened her eyes to see that Bess was bending over her and struggled to sit up.

‘What is the matter?’ she asked groggily. ‘Have the Revenue men come?’

‘Nay, lass. ‘Tis the stranger you brought from the beach. He’s burning up and calling out loud enough to waken the dead. ‘Tis as well your brothers have not yet returned.’

‘Why?’ Morwenna leapt out of bed and pulled on a wrapping gown that lay over the chair. ‘Michael sleeps like one of the dead and Jacques is the same.’

‘Aye, well, best they don’t hear what I think I heard him call out.’

Morwenna looked at her curiously. ‘He must have been having a nightmare. What did he call out?’

‘Your name and then …’ Bess glanced cautiously over her shoulder ‘… I’m not sure what he said then for ’twas slurred, but I think he said “Nest of traitors,” but I can’t be certain.’

‘If Michael heard that then he would think the worst. Yet on the beach he asked my name and I told him. It might just be that it was all that came to his mind. Mayhap you imagined the rest, Bess.’

‘I might have done for ’twas not clear.’

Morwenna went ahead of her servant into the bedchamber where her patient lay. Bess had left a lantern burning and she saw immediately that the man was ill. He had thrown off his covers and she could see his body was covered in a fine layer of sweat. Going to him at once, she touched his forehead.

‘He is in a bad fever, Bess.’ There was no doubting that he was ill now. ‘I must bathe him with cool water. Brew the tisane you use when any of us is ill, please. We’ll do our best for him, whoever he is.’

‘You’ll have to keep him quiet once Michael returns or all your good work will be for nothing.’

Morwenna didn’t answer, but a cold shiver ran down her spine as Bess left the chamber. If Michael suspected the man had come here to spy on them he would show no mercy. Gazing down on him as she began to bathe his body with cool water, Morwenna felt something protective stir inside her. She did not know who this man was and he could mean nothing to her, but he was a human soul and entitled to her care whilst ill.

‘Morwenna Morgan … no …’ he muttered suddenly, flinging his arm out in an arc. ‘Jane … please don’t leave me …’

‘Rest easy, sir. You are safe now,’ Morwenna said, stroking his damp hair back from his forehead.

‘Nowhere … no place to hide …’ the man muttered. ‘Alone … she’s gone, nothing left … Morwenna … Morwenna …’ He cried out in anguish, ‘I’m sorry, Mother. I didn’t mean to kill him … it wasn’t my fault … please …’ He was tossing in agony, clearly suffering from the dreams or memories that plagued him. ‘Forgive me … forgive me …’

Morwenna’s heart wrenched. ‘You are forgiven. Hush now.’

‘No, no, she will never forgive me.’

Wringing her cloth out, Morwenna bathed his forehead again. She thought he felt a little cooler but it was clear he was still wandering in his mind. Was her name on his lips because she’d told him who she was on the beach? What was it that haunted him so much?

‘It’s all right,’ she whispered softly close to his ear. ‘You’re safe here with me. Hush now and you will soon feel better.’

His eyes flew open suddenly and for a moment he stared up at her. ‘You’re beautiful,’ he said and leaned forwards, as though he would sit up or touch her. Then his eyes closed and he fell back against the pillows. ‘Morwenna … lovely name …’

‘Here, my lovely, give him a sip of this.’

Morwenna turned as Bess entered bearing a tankard of hot liquid. It smelled strongly of cinnamon and she knew it contained brandy and the herbs that were effective for fever.

‘Help me lift him,’ Morwenna said. She took the cup, one arm beneath the man as she and Bess lifted him into a sitting position. ‘Open your mouth, sir. This tisane will help you recover.’

She pressed the edge of the tankard to his mouth, unsure that he would respond or could even hear her. Surprisingly, his lips parted and she was able to tip a little of the mixture into his mouth. He coughed and choked, but when she tried again he allowed her to pour some of the mixture into his mouth and this time he swallowed it easily. When she tried again his hand gripped her wrist, pushing her away.

‘Enough,’ he muttered. ‘No, Mother, enough.’

‘He must be sick if he thinks you’re his mother,’ Bess said with a sniff. ‘He looks cooler now. He’ll probably settle. Go back to your bed, lass.’

‘No. If I’d thought he was truly ill I wouldn’t have left him last evening. I’ll sit with him for a while, Bess. You go to bed. If he is ill for a few days, we’ll have to share the nursing and you need your rest too.’

‘So do you, miss, but have it your way. Just watch yourself if he starts to fight—and don’t let him shout out. Your brothers came in a few minutes ago and they’ve gone to their beds.’

‘‘Tis nearly morning. Where have they been all this time—and on a night like this?’

‘The storm blew itself out a while back,’ Bess said. ‘The darker the night the better for the “gentlemen”.’

‘I dare say it was some such business,’ Morwenna said and yawned behind her hand. ‘Go to bed, Bess. In a couple of hours it will be time to get up again.’

Morwenna sat in a solid oak-carved chair with a high back. She had made cushions for its seat and the centre splat had horsehair padding covered by tapestry and studded each side to make it comfortable. The first time Morwenna had brought a survivor to this room she’d installed the chair so that she would at least have some comfort as she watched over her patients. Mrs Harding had been very ill, but Morwenna had nursed her back to health and she’d been overwhelmed by gratitude when she was able to return to London and her husband.

‘We are cloth merchants, Morwenna,’ Mrs Harding had told her as she took an emotional farewell. ‘My husband will always be pleased to have you stay with us. If ever you should be in trouble, think of me, my dear, for I would do anything to help you.’

‘Thank you.’ Morwenna had smiled and kissed her cheek. ‘If ever I am in London, I shall seek you out, at least for a visit.’

Morwenna sighed at the memory. It was unlikely she would ever go to London. Her hopes of making a good marriage had gone when her mother died. Since her father’s death she had been little more than a servant in her half-brother’s house. Michael had resented the woman who had taken his dead mother’s place and she suspected that he might resent her, too.

She would not brood on her life no matter how hard or hopeless it might seem at times. While she had Jacques to make her smile she would find the courage to face each day, though there was little else to make her smile in this bleak house at the top of the cliffs.

Sitting down again, she studied the man in the bed. His hair had dried now and she saw it was dark blond. On the beach he’d looked colourless, but now there was a flush in his cheeks. When he’d opened his eyes for a moment she’d seen they were a greenish blue; his nose and forehead had a patrician look, which gave him a slightly forbidding expression, but his mouth was soft and sensual. She felt tempted to kiss him as he lay sleeping, her cheeks growing warm as she realised her own thoughts.

Was she so starved of love that she would consider lying with a stranger? He had beautiful strong limbs and there was not a part of him that she had not seen as she bathed him with the cooling water. A little smile touched her mouth. She’d nursed her brothers before this, so why was she behaving as if she’d never seen a man naked before?

Time passed and she closed her eyes for a while, woke and realised she’d slept, and then she looked at the bed. Her patient was still there, apparently sleeping peacefully. She’d thought he might have disappeared for surely she’d conjured him out of her dreams. Men like this one did not come into her life often. He was every bit as handsome and powerful a man as her brothers, but there was something about him that made her pulses race. Something about his mouth that made her want to kiss it.

Giving herself a mental scolding, Morwenna laughed softly. She was a fool even to consider such a thing—especially if this man had come here to spy on them.

‘Why are you laughing?’

Her eyes were drawn to the bed and she saw that he was looking at her. Getting up from her chair, she moved closer to the bed. He seemed to be awake, but was he still feverish? Sometimes patients appeared to be normal, but when you touched them they became violent and tried to fight you. Her brothers had often tried to get out of bed while still too ill to stand and she’d had to fight to keep them there.

‘I was thinking foolish thoughts,’ she said. ‘You were ill and I bathed you to take down the fever. Are you feeling better?’

‘I don’t know.’ He stared at her in bewilderment. ‘My head hurts like the devil. I was dreaming … I thought my mother …’

‘We carried you here from the beach. Your ship foundered on the rocks, sir. You have a nasty cut on your head.’

‘Who are you?’

‘Morwenna Morgan. I told you my name when I found you last night. For a moment you were conscious, as you are now, and then you fainted.’

‘Did I? I don’t recall.’ He frowned, his eyes moving about the room as if seeking something familiar. ‘I don’t remember anything. Where is this place?’

‘This is Deacon’s House. It belongs to my elder brother, Michael. We live on the Cornish coast. Ships are too often driven in on the cruel rocks in our cove. We do what we can to help the survivors and the villagers bury the dead.’

‘And then take what you can scavenge from the wreck—is that not the custom in these parts?’ He wrinkled his brow. ‘I do not know why I should remember that but nothing else.’

‘You cannot recall even your name?’

‘No.’ He drew a hand over his forehead, as if it pained him. ‘Is that usual after being washed up from the sea?’

‘Perhaps, though I have not known it to happen before,’ Morwenna said. ‘It may be the bang to your head. Have you truly no memory, sir—or any idea why you came here?’

‘I can’t remember anything.’

‘You must surely remember your own name? You called out things in your fever, personal things concerning your mother and other things that I couldn’t quite make out.’

‘Did I? If they haunted me, then they have left me now. Was there no clue to my identity?’

‘None. My brother found nothing in your clothing. Your coat was gone, abandoned or cast off perhaps as you tried to swim for the shore. You can recall nothing of the storm or how you came to our cove?’

‘No. My mind is a blank, there is nothing but the sea raging about me and then I opened my eyes and saw a beautiful face. She said her name was Morwenna Morgan … was that you?’

‘Yes, sir. It was. I found you in the inlet, which is away from the main beach. My brother Jacques helped me bring you here.’ Morwenna placed a hand on his forehead. He was still warm but cooler than before.

He threw back the covers, as if he would get up, then glanced down at himself, realising that he was naked. ‘My clothes?’

‘What’s left of them—your breeches and boots—are drying in the kitchen. Your shirt and coat were, I fear, lost to the sea—and there was nothing to identify you, no papers or even a ring on your hand. Your baggage must have been lost with the ship, but there was one small bag I found near where you lay. It is lying here on the window seat.’

‘Please bring it here,’ he said and made an effort to sit up but fell back with a moan. ‘My blasted head. Please open the bag for me and see what is inside. It may tell us something of who I am.’

Morwenna fetched the bag and brought it to the bed. Opening it, she found brushes, crayons, bottles of powder in different colours and some soggy boards that she knew might be used by an artist. There was also a small leather purse that felt quite heavy. She tipped the contents on to the bed and twenty gold coins tumbled out.

‘It would seem that you have some money and perhaps you are an artist, for these things must belong to an artist.’

‘Yes, so it would seem.’ He frowned. ‘Is there nothing else that bears my name?’

‘I don’t believe so.’ Morwenna felt something in a side pocket and inserted her fingers, drawing out a small metal token. It had writing on one side. She read the lettering and frowned. ‘I think you must be a gambler, sir, for this is a token from what would appear to be a gaming house in London.’

‘Let me see, please.’ He took the little token and studied it. It bore the words Harlands of London and was a token for five guineas. ‘It would seem that I have recently been in London, would it not?’

‘Yes, I think you must have been,’ she said. ‘Perhaps you won the money there at this place? There are no clues to your identity, but if you returned to London and asked someone might know you at this place.’

‘Yes, thank you,’ he said and closed his fingers over it with a kind of desperation. ‘I must hope that someone will tell me who I am.’

‘Do not despair just yet, sir,’ she said and smiled at him. Now that she suspected he might be an artist she was no longer afraid that he had been sent to spy on her brothers. ‘You had a nasty bang on your head and the loss of your memory may be temporary. In time it will return to you.’

‘Perhaps. You are good to be concerned for a stranger.’

‘I have helped others in similar circumstances, sir. I am glad to have been of service to you.’

‘Yet I should go,’ he said. ‘I must not be a burden on you. Pray turn your back, Mistress Morgan. Preferably leave the room. I need to relieve myself.’

‘Lie still and I shall bring you the chamberpot, sir.’

‘Turn away for your modesty.’ He put his legs over the side of the bed, touched the floor with his feet, then moaned and fell back. ‘Damn it, I’m as weak as a kitten.’

‘You have been shipwrecked, sir, and your head bled from the blow you received. You will feel dizzy at first. Lie back and I’ll give you the pot.’

Morwenna reached beneath the bed and brought out the chamberpot. She handed it to him and retreated to the other side of the room to gaze out of the window. The sun was coming up over the sea, turning it pink and orange; this morning it would be as if the storm had never been except for the wreckage on the beach and the man in her bed.

‘Have it your own way.’

The sounds of him using the pot kept Morwenna looking out to sea until he had done. She turned as she heard him place it on the chest beside the bed with a grunt, then returned to take it by the handle.

‘I am used to nursing my brothers, sir. Please do not be embarrassed. Someone will need to care for you while you are forced to stay in bed.’

His gaze narrowed. ‘Have you no servants to do the menial tasks?’

‘How do you know I am not a servant here?’ she challenged.

‘You spoke of living here with your brothers—besides, you are too proud a wench to be in service, methinks.’

Morwenna laughed. ‘At least then I should be paid for my work. My mother was a lady and my father called himself gentry, though he had rough country ways. However, they are both dead and we have little money. I do have one servant. Bess was our nurse and she helps me now that we have no other servants.’

‘Where are you going?’

‘To empty this, sir. If you wish for it, I could bring you something to eat. There is a tisane by your bed. It must be cold now, but it will still taste good. I shall return soon with food and more drink.’

‘It is not fitting that you should wait on me or do these things for me. Send your servant instead, Mistress Morgan.’

‘Bess is asleep and I shall not wake her.’

‘I am grateful for all you have done, Mistress Morgan, but I feel it wrong that a young woman of your breeding should do such things for me.’

‘You are no different to me than my brothers,’ Morwenna lied. ‘As soon as you feel able to leave your bed you would do best to leave us, sir—but until then I shall help you as best I can.’

She went out before he could answer her, pride and temper carrying her down the stairs. Who did he imagine he was to tell her what was right and proper? She was accustomed to doing much as she pleased, for even Michael did not interfere unless it suited his purpose.

It was awkward that the stranger had lost his memory. Michael would want to know who he was and why he was here—he suspected any stranger that came to their village. Morwenna would not have him mistreating the stranger. She must find a way to keep him safe until he was well enough to leave them.

It might be best to tell her brothers that he was an artist—and if necessary she could invent a name for him. Better that than leave Michael suspecting the worst about the stranger in their midst.

The stranger smiled as the door closed with a little snap. The fire in Morwenna’s eyes as he’d told her it was not fitting that a woman of her breeding should care for him had amused him. She was proud and beautiful and it seemed that she had compassion, for she’d taken him in without knowing who he was or where he came from. His smile faded as he tried to remember who he was and why he was here in Cornwall.

The token in his bag suggested he’d once been in London. Why had he left town to come to a part of the country that most thought of as God-forsaken?

Someone had said that recently. At least, the phrase had come easily to his mind. He seemed to recall that he found the Cornish coast rugged but beautiful—that he had either painted it before or was looking forward to painting it in the future.

Perhaps that was his reason for being here. If this bag belonged to him, he must be an artist. Was he a successful one? Did he have money—more than the few gold coins lying on the bed by his side?

Something was not quite right. He felt that there was more to his life than that of an itinerant artist, moving from place to place to earn a living as best he could.

Was he a gambler down on his luck? Did he have a family and where did he belong?

Something told him that he was not married. He had a feeling that he was a lonely person and that there was an empty place inside him.

Now why did he feel that? For a moment a feeling of panic swept over him. Why could he not recall even his name? Supposing he never did?

Fighting his panic, he focused on the girl who had just left the room. She was right to suggest that he must seek his identity in London. Whatever his reason for being here, he must return to town and try to discover his name and family.

Once again a smile touched his mouth as he thought of Morwenna. She and her brother had carried him to their house and the girl had nursed him through the night. He dimly recalled feeling very ill and crying out as he tossed and turned, but whatever had haunted him then had gone, lost in the mists of amnesia. When he’d woken he’d seen the girl sitting in her chair near the bed. She was laughing to herself … at her own thoughts. The look on her face had intrigued him. What was she thinking? She might almost have been dreaming of her lover.

Something in him had rebelled at the thought of her with a lover. Perhaps he’d spoken out of turn, telling her that it was not fitting for her to do what she’d done. Had she left him on the beach he might have been killed, though the villagers would find little profit in robbing him for he wore no jewellery—at least he wore none now. Could the girl or her brother have taken it?

No, that was an unworthy thought! Had she been a thief she would have taken the money from his bag. If he wore no jewellery, he could not be anyone in particular—a gentleman often wore a signet ring with a crest, but he did not.

Yet instinctively he knew he was of gentle birth. Perhaps he came from an impoverished family and had chosen to make his living from his talent, if he had talent? He was still not certain that the bag belonged to him. Other men would have been on the ship that went down.

One of the first things he must do when he felt able to get up was to find something to draw on and then he might discover if he could be a painter. Until then he could only surmise that he was an artist.

He would have liked to get up, but for the moment he felt too ill. He must just lie here until his strength returned. Since he had nothing more to occupy his mind, he would think of Morwenna and that look in her eyes …

‘Will you take this tray up to him?’ Morwenna asked when Bess entered the kitchen. She had prepared a plate of hot crispy bacon with eggs and bread fried in the fat, also a mug of grog made from ale spiced with cinnamon and a dash of brandy. ‘He was awake and he may be hungry or thirsty.’

‘This is food for a hearty appetite,’ Bess observed. ‘If he is sick he needs porridge or gruel to ease his hunger.’

‘I think he would throw it at you. He cannot yet leave his bed for he is dizzy, but there is little wrong with him—though he claims he does not know his own name or from whence he came.’

‘You think he lies?’

‘I don’t know. Michael mustn’t suspect it or you know what will happen—but he ought to leave this house as soon as he is able to walk.’

‘Aye, I know it. Give me the tray. I’ll ask if he wishes for anything more.’

‘I emptied the pot and will bring it up with a can of water. It’s my day for cleaning the bedchambers, though my brothers will sleep clear through the morning if I know them.’

‘Least said the better, lass. They were out helping to rescue men from the sea last night. No need to say more.’

Morwenna nodded as Bess picked up the tray and went out. She cut a slice of cold ham, placed it between a thick slice of bread and munched it as she waited for the water to boil. A part of her was eager to see the stranger again, though her common sense told her she would be best to let Bess care for him. By his manner and his look he was gentry, though perhaps like her he had little money. Why would he make his living as an artist if he were wealthy?

She shook her head. It was unlikely—though, sometimes, rich aristocrats spent time sketching simply to amuse themselves, of course. Twenty gold coins were not a fortune, but it was more than Morwenna had ever owned in her life.

A little smile touched her lips as she thought how handsome he was, but she shook her head almost at once. She was a fool to daydream over a stranger. She could not deny the instant attraction she’d felt, but he was unlikely to have felt the same.

It was because she seldom saw anyone other than her brothers, of course. Morwenna had no life of her own, nor any amusement or pleasures outside of what she made for herself.

Bess was always telling her to go to her mother’s sister in London, but she knew her aunt to be an unkind, bitter woman. She’d buried two husbands and she had money to spare, but she was unlikely to spend it on the daughter of a man she despised.

‘My sister, Agnes, never forgave me for marrying your father,’ Morwenna’s mother had told her when she was ill. ‘She warned me that he would break my heart or drive me to an early grave. It is not your father’s fault that I am sick, dear heart. I was always sickly, which was why my sister warned me against marriage to a man like William Morgan. I needed a gentle, kind man, but I loved him and I followed my heart. I do not regret it, though the bitter winds here have been my undoing.’

Morwenna had mourned her mother more than her father, though she knew that he, too, had grieved deeply, and despite his denials it was love of his dead wife that had caused him to neglect his own health and die of an infected boil on his neck. Morwenna would have cleansed it and bound it for him, but he would not let her touch him. At the end the physician told her that the poison had seeped into his blood and led to the fever that ended his life—but perhaps he had not wanted to live. He had quarrelled fiercely and often with his eldest son and ruined the family with his gambling and bad investments, though no man could govern the weather and a risky cargo lost at sea was the undoing of more than one merchant adventurer.

Her father had been given to risky ventures, but he had always been loyal to Queen Bess in her time and the King, even if he disliked his politics. It had been on a visit to court after his first wife died that he’d met and married Morwenna’s mother, bringing her back to this house at the edge of the cliff. Jenna Morgan had always dreamed of taking her lovely daughter to court, but the girl’s father had forbidden it.

‘No good giving the girl ideas above her station. She’ll marry a local man and do what I think best for her,’ he’d declared, but he’d never bothered to find her a husband and Michael was too wrapped up in his work to think of such a thing.

Carrying the empty pot in one hand and a pewter can of warm water in the other, Morwenna started up the stairs. Pausing outside the door of the guest chamber, she heard a curse and then a muffled laugh.

‘Damn you, old mother,’ the stranger muttered. ‘Have it your own way, crone. I’ll suffer you to help me since I cannot do it myself.’

Opening the door, she went in and saw that her patient had managed to struggle into the hose and breeches he’d been wearing when she found him. Bess had provided him with one of her father’s best shirts and a doublet of well-worn leather. He was now lying on the bed, propped up against the pillows. She noticed that he had eaten the food and had the tankard of warmed ale and cinnamon in his right hand. His gaze fell on her as she entered and he frowned.

‘I brought you some water to wash, but it seems you forestalled me.’

‘I used the cold water in the jug, with Bess’s help,’ he said and made a wry face. ‘Did I not tell you it is not fitting for you to wait on me, Mistress Morgan?’

‘You’ll tell her until you be blue in the face.’ Bess chuckled. ‘Mistress Morwenna be a law unto herself, sir. She never minds me nor yet Master Michael, though sometimes we all have to take care for he has a rare temper.’

‘Bess, do you not have something to do downstairs?’ Morwenna asked. ‘Take the tray down. I’ve work to do up here but we’ll start the baking when I come down.’

She turned to the door when the stranger spoke. ‘I’ve decided you should call me Adam, mistress. ‘Tis not my name, but it will do as well as any until I know my own name.’

She stopped, turned to look at him. ‘Adam was tempted by Eve and thrown out of the Garden of Eden for his sins. This house is not Eden, sir—but you should think of leaving as soon as you can walk. My brother does not care for strangers in the house.’

‘What does he have to hide?’

Morwenna’s eyes narrowed in suspicion. ‘You should not ask. Believe me—you would not like to see my brother in a temper.’

‘Does he treat you ill?’

‘He shouts at me and orders me to do his bidding, but I keep a still tongue and then do as I please. I am his sister and Jacques would stop him if he lifted a hand to me. Besides, I am useful. Michael knows that I would leave this house if he once struck me.’

‘Where would you go?’

‘I do not know. Perhaps to my aunt’s in London.’

‘If she would take you in, you should go. A house like this is not fitting for a woman like you.’

‘Indeed? What do you know of this house or my family?’

‘Only what you have told me. Forgive me, mistress. I dare say you think me arrogant, but I am grateful for your help. Let me give you some of this money to start a new life somewhere else.’

‘You presume too much, sir. I need no help from you nor anyone else. If I needed to, I could find my own way in the world. I am strong and I can work.’

‘You might find it harder on your own than you think,’ he replied. ‘The world is a wicked place, Mistress Morwenna. You need someone to protect you when you leave—your aunt or—’

A look from Morwenna silenced him. Once again he looked rueful.

‘I have said too much. Away to your work, mistress. I thank you for the food and your kindness. As soon as I am able I shall leave this house, but I shall not forget you.’

‘I pray that you recover your memory soon, sir. I need no thanks or recompense for the little I did—but ‘tis for your own sake that I tell you to leave as soon as you are able. Michael does not care overmuch for strangers in his house.’

He inclined his head, but said no more. Morwenna left him and went slowly along the narrow passage to her own room. She would clean her chamber and Bess’s, leaving her brothers’ bedchambers until later when they were out about their own business.

She had warned the stranger to leave for his own good, but knew she would regret it when he had gone. Yet she could expect nothing from this chance encounter. Her life would be the same when he had gone. If she wanted more, then she must either go to her aunt or look for a husband nearer to home.

There was only one man who would ask her to marry him, but she disliked the man who was in charge of the local militia. Captain Bird was waiting for his chance to ask for her hand, but she would rather be single all her life.

Captain Bird was a Revenue Officer, but he had struck up an odd relationship with Michael. Although he told her nothing, Morwenna knew that her brother was involved in smuggling goods from France. The local gentry paid him well for brandy and silks that had never paid a penny in tax. That alone would see Michael hang if he were ever taken, but somehow he always seemed to know when the soldiers were coming and he was never in the house. It was Morwenna who had to fend off their questions—and yet Captain Bird never made more than a perfunctory search of the house before leaving them in peace.

Why should he be so accommodating? Did he and Michael have some understanding?

It would not be unusual for money to change hands in such business. If Captain Bird took bribes, he was little better than the smugglers he was supposed to arrest when he found them.

Morwenna was frowning as she began to rub beeswax perfumed with lavender oils into the solid oak furniture. She had drifted from one day to the next, vaguely unsatisfied with her life, but unsure of what to do to change it. Now she was aware of feeling restless. Unless she went to live with her aunt she really had little choice, for she knew that it wasn’t enough to be willing to work hard. She wasn’t as innocent as the stranger imagined and knew what might await her if she went to London or one of the big cities to ask for work. She would find herself being forced into a profession that would shame her.