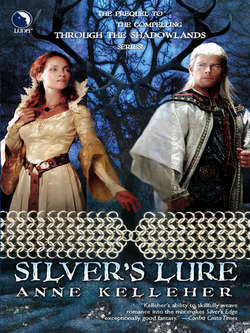

Читать книгу Silver's Lure - Anne Kelleher - Страница 9

2

ОглавлениеFaerie

“Auberon?” Melisande’s soft voice broke the stillness of the summer twilight, taking the King of the sidhe entirely by surprise, penetrating the soft pink fog of dream-weed smoke. His queen seldom attempted the winding climb to his bower at the top of the highest ash of the Forest House because she, unlike almost every other sidhe, was terrified of heights. It was one reason he’d chosen her among all the others to be his Queen. Now she perched in the archway of the bower, quivering only slightly. Her long fair hair, fine as swan’s down, feathered around her shoulders, down her back and chest. In the orange glow of the setting sun, it gave the illusion she was covered in white feathers.

She’s begun the change, he realized, and looked down at his own furred flanks. When the change in both of them was complete, it would be time for their daughter, Loriana, to assume her place as Queen of the sidhe and all the creatures of the Deep Forest. Presuming, of course, that all Faerie wasn’t turned into some foul wasteland overrun by goblins. It was beginning to seem like a distinct possibility.

He extended a hand, but she didn’t reach for it. Instead she looked at him, not with fear, but suspicion and he realized she was trembling, not with terror, but outrage. “What’s wrong, my dear? You look upset.”

“Is what your mother told me true?”

Anger flashed through him, but he controlled himself enough to smile tightly and beckon. Finnavar was an interfering old crow who belonged, like the rest of the sidhe who completed the change, in the Deep Forest. “I can’t imagine what sort of mischief she’s making now. Come sit, my dear. Tell me all about it.”

Melisande raised her chin. “Should we call it mischief when it’s our daughter’s choice that’s being bargained away? And if we do, I don’t think she’s the one making it.”

Auberon clenched his teeth. In the midst of everything else, his mother couldn’t resist causing trouble. She stubbornly refused to leave the Court, creating an embarrassing situation. It was as if she didn’t quite trust him to rule. Despite all his directives to ignore her no one really did. Her instincts both for causing trouble and ferreting out information remained intact. “Let’s talk.”

“You admit it.”

“Beloved, I—”

“Oh, enough. I’m not your beloved.” She stalked into the room, anger making her sure-footed. “Is it true you promised Timias that you would ask Loriana to consider choosing him to be her Consort?”

“My dear, you’re shaking—there’s no need for unpleasantness—”

“Unpleasantness? Auberon, our daughter is not a prize to be awarded or a—a possession to be handed over. How could you listen, let alone agree—He was raised beside you in the nest—If you were mortal, you’d be brothers and such a thing not even considered.”

“Melisande.” He picked up his pipe. “Don’t you understand it’s not important? I don’t think he’s coming back—I never expected he’d be back, to tell you the truth.”

“You didn’t?”

“Of course not. It was as absurd an idea as I’ve ever heard—learn druid magic and bring it here to Faerie.” He picked up her hands and brought one, then the other to his lips. “Sweet darling queen, it was a way to find something for him to do.”

“So what exactly did you agree to?”

Auberon shrugged, picked up his pipe and tapped dried flowers into the bowl. “He asked me if I’d approach Loriana and ask her to consider his suit. It seemed a small enough thing—considering I didn’t think I’d ever have to do it. Where was the harm, after all? It made him feel useful, gave him a purpose.”

“And what if he does? What if he comes back?”

“You have been talking to my mother, haven’t you?”

“Loriana is of an age to consider such things. Look at us, Auberon—you and I are clearly entering our change. When your mother tells me you’ve made some kind of bargain involving our daughter—”

“Enough, Melisande. There’s no bargain involving Loriana or anyone else. Timias has not been seen in—I’ve forgotten how long exactly. Maybe you should ask yourself why my mother sees the need to bring it up now?”

“She’s concerned. The Wheel’s turning—we have to prepare ourselves and everyone else.”

The dream-weed hit his head just as she spoke. It elongated her words, separated out the subtle shades of tone and melody, turned the light around her face ethereal and fey. He was captivated by the glints of pale yellow and tender gray in her hair and in her eyes. In all the time he’d known her, he’d never noticed these before. A vein beneath her ear beat a steady tattoo in her throat, in time to that which pulsed up through his feet. The firs stood straight and tall, black against the indigo sky, the drooping branches of the enormous willows all silver by their sides. The first stars had already appeared. A low pounding throbbed through the trees, and the leaves rustled as the branches swayed in time.

A horn rose in the distance, its note pure and piercing as a shaft of morning sun. It stabbed into his awareness, made his ears ring and his head ache.

“Auberon?” Melisande shook his arm. “Did you hear that? That’s the alarm. The goblins are rising.”

There was a screech in the doorway. Finnavar stood there, looking like an enormous raven cloaked in black feathers, her nose and chin fused into a long shiny beak, her arms folded back. “Where’s Loriana?” she croaked. Her beady eyes darted right and left, her feathers gleamed blue in the purplish shadows. “Have you seen her? I’ve looked everywhere.”

What little color there was in Melisande’s face drained away. “She’s been told not to leave her bower at dusk.”

“She’s not there now,” the old sidhe screeched.

“She has to be,” cried Melisande as the dull vibration grew stronger, and from somewhere far away, they heard a faint roaring, growing ever louder as the wind carried it closer.

“She isn’t,” answered Finnavar. “Follow me.” She flapped awkwardly off without another word.

Melisande pulled away from Auberon and rushed out the door, nearly colliding with Ozymandian, the captain of the guard. He scrambled past her, brandishing his spear. “My lord.” He sketched a salute, then said, “My lord, you must come. Something’s roused the goblins—all of them, apparently—and it seems they’re headed this way.”

Red steam rose from fire pits of glowing molten rock, seeped from crevices in the floor and hissed from fissures high within the cavernous chambers and passageways that were the realm of Macha, the Goblin Queen. The floors were slick in some places and sticky in others, and the smell of excrement was everywhere. Timias shrank behind an enormous boulder. The air was thick with the steady throb of drums, a sound so constant he sometimes thought it must be coming from inside his own skull. He cocked his head and listened to the squeals and screams and bellows echoing from the chamber, trying to decide if he dared to take the only direct route he knew that led to the surface of Faerie. The druid spell of banishing had finally worn off. He could feel the tattered remnants shredding off him like an old cloak, one thread at a time. He had never expected it to be as effective as it was, for it not only kept him from Shadow—anywhere at allin Shadow—but it prevented him from returning to Faerie, as well. For a mortal year and a day, he’d been trapped in the strange nether places of the World. He was impatient to return, and he risked a slow death by searching for another way to the Forest House. The effects of the banishment still lingered, preventing him from directly returning to the Forest House.

He’d counted on Macha’s halls being silent, the goblins curled up fast asleep, thin and gray as the ghosts of the mortal dead whose flesh they consumed. But something must’ve happened, he mused, in the time he’d been banished. Somehow they’d gotten a taste of living flesh.

It was possible he might find another way to the surface, but he could just as easily encounter lairs filled with starving hatchlings. If the goblins were this lively, they were certainly copulating. The cloak of shadows, woven with a mortal druid on a Faerie loom, might not fool the goblins. Like a river of velvety water, the cloak flowed out of his hands, vaporous as fog, dense and wet as the Shadowlands themselves, its one edge jagged where Deirdre had ripped it in half. He wrapped it around himself, careful to tuck it well over his face and around his hands. He was more afraid of how he’d smell than anything else. But he had to risk that a wafting scent of Shadow, while alluring, would not be as riveting as the sight of a sidhe scurrying along the perimeter of the cavern.

With a last check to make certain he was completely covered, Timias edged down the widening passageway, careful to keep to the sides where the shadows were thickest and his cloak provided the best cover. But he had not counted on the stench.

The closer he got to the central hall, the stronger it was. It pervaded his nostrils, crept into his skin, insinuated itself into the crevices around his nose, his fingers. It filled his mouth and made him gag. Dizzy, eyes burning, Timias crept along the Hall, trying not to breathe too deeply. It was worse than the foulest cesspit, the fullest charnel pit in Shadow.

Behind him, a noise made him flatten himself against the jagged outcroppings along the wall, and as he watched in horror, he realized the source of the wet trail of slime. It was blood—mortal blood, gelling as it dried. It dripped from the squirming, screaming, struggling bodies of the mortals the goblin raiding party was now dragging along or had slung over their backs. Some struggled and kicked more than others, but one thing was very clear to Timias: They were all still very much alive.

The coppery scent of the blood, the acrid tang of urine and the fetid aroma of feces, bowels opened and bladders spilled filled Timias’s senses. Timias waited until the tramp of goblin feet had faded. His eyes were finally adjusting to the reddish light, and he crept, one hand clamped around his nose and mouth.

Macha, the enormous queen, crouched at the peak of her throne, her beady eyes bright in the nightmarish light. She uncoiled and coiled her tail, reflexively, surveying the scene before her. The goblins were all over the hapless humans, tearing them apart in a frenzy of showering blood and ripping flesh. The ragged end of a leg was tossed up toward the queen; she snarled, reached for it and crammed it into her mouth. Red drool spooled down her chest as she chewed and swallowed and grinned. Timias could not look away.

With the same casual ferocity with which she crunched the bones and swallowed them, Macha reached for the nearest male, threw him on the ledge and proceeded to raise and lower her massive body over his, ramming him nearly flat with the force of her thrusts. She bared her fangs and howled, which sent up a chorus of answering screeches. The smoke and the smells and leaping goblin hordes were making Timias dizzy. He pushed himself hard up against the wall, trying to hold on to his bearings as a wave of nausea swept over and through him, nearly dragging him to his knees. He felt his legs begin to buckle and he clutched the cloak hard around himself, even as he tried to lean back. He tried to back up and realized he was prevented by a tail.

His tail.

The cloak floated off his shoulders as he swung around, staring at the shadow that stood in stark outline against the rocks. His shadow. For a moment, Timias wondered if this was some trick of the light, some result of the druids’ curse of banishment. But no, he’d been himself in the passageway. He was sure of it. Of course he was. He remembered looking down and being grateful he was wearing boots. Boots. He looked down at his feet, and saw clawed toes bursting through the tips.

Behind him, he heard a hiss and a cackle that was taken up and turned into hoots and shrieks. Timias turned to see the goblins—every one of them, including the queen—looking back at him. And they were laughing. Or what passed as laughter. They were pointing at him, slapping each other on backs and rumps, rolling between the fire pits in unrestrained glee. What was it, he wondered. What’s wrong with me? Why are they all staring? What’s so funny?

And then he looked down at himself and realized that he not only appeared to be a goblin, he alone was wearing clothes. Am I mad? he wondered in an instant. But he didn’t have time to consider how this transformation had taken place, or why, because the other goblins—no, he told himself firmly. Not other goblins at all. The goblins. The goblins were creeping closer. Inspiration born of desperation gave him an idea and he knew what he had to do. With a bound, he decided to play the best of it he could. He swaggered out, into the center, gesturing and posturing. He held his maw shut, then bent over and pretended to break wind. Then he began to pull the clothes off, one at a time, throwing them into the assembly. The goblins shrieked and capered and he looked up, into the eyes of the queen.

“I don’t know you,” she said. Her black forked tongue flicked out and she sniffed, as if teasing out his smell from among all the other odors swirling through the cavern.

He felt as if her eyes were boring into the center of him, seeing him for what he really was, and he felt himself quail. Don’t collapse now, fool, he told himself. She was intent on looking for weakness, sniffing it out, determining which of all her many subjects she would allow to live. The weak she would kill. He forced himself to stand straighter, even as he noticed how her egg sacs bulged beneath her tail, how clear fluid spilled down the insides of her thighs, pooling around her feet.

Saliva spilled from the corners of his mouth, oozed down his chin. He was alarmed to realize he found the odor as appealing as honey, and he shuddered, appalled by his body’s own response.

“Name?” she said, watching him closely enough to kill him in an instant.

Did he have a goblin name, he wondered? The name he’d used among the mortals had simply risen to his lips the first time he was asked. What was he supposed to call himself?

“Name?” she repeated. She took a step closer and the nearest goblins stopped eating or copulating and turned to watch.

What was he expected to say, he wondered? Timias? Tiermuid? He opened his mouth and a bleat came out. The court laughed.

The queen narrowed her eyes and the corners of her maw lifted. He wasn’t sure if she was smiling or if she was merely opening her jaws wide enough to bite off his head. “Name?”

“T-T-Tetzu.” He heard himself say the word as his goblin tongue tried to form the syllables of his name, either of them.

“Gift?”

“Gift?” Timias repeated, trying to look as if he didn’t understand the meaning of the word. What could she possibly want from him?

“Macha likes gifts,” she said. She coiled her tail under herself almost daintily and to his surprise, his own nearly naked body responded to the invitation it portended. She leaned closer, sniffing the air around his neck, and he felt his ruff rise.

“Xerruk bring Macha gifts,” snarled a voice behind the queen. He handed her a head, the lips still moving, the eyes still aware.

Timias saw his chance. With a speed born of complete and utter hopelessness, he bolted around the nearest fire pit, racing to the opposite passageway.

But the queen’s interest, once roused, was not so easily dissuaded. As he reached the opening, she took off after him and the entire Court followed. Timias pelted up the passage, praying and hoping the sun was out, that the hot light of day would drive the goblins back into their lairs.

Dank air seared his lungs. He imagined he could feel her vicious claws tearing him to shreds, ripping out his throat, and he pumped his arms and legs as fast as he could run. He burst out, into the trees. A few stars twinkled overhead in a pale purple sky. If it was dawn, he had a chance. He raced through the trees, the goblins pursuing him in full force after their queen, howling and shrieking.

The farther he ran, the darker it got, and Timias realized that far from being dawn, which was the worst time of day for the goblins, it was dusk, the best.

The darkness was giving him some advantage, however, for he was able to blend in with the trees. He ducked around the trunk of one enormous oak and slumped against it. He felt his flesh shrivel as it touched the rough-ribbed surface, felt his frame collapse into itself. His tail curled up and under his buttocks and disappeared, his goblin skin softened and gave way to smooth pale skin. Somehow, he wasn’t goblin anymore. I am sidhe. Not mortal, not goblin. Sidhe. He didn’t understand what had happened, but he knew he could never tell anyone. Fooling mortals was one thing, becoming a goblin quite another. Not away from the scent of the others. He sank down, and the horde surged past.

A blast of horns filtered through the trees, and Timias realized the sidhe had been alerted. He wondered if Auberon and his Court realized how close Macha’s lair really was. Light flashed above the treetops, limning the sky with brief glimpses of green and blue and gold, fleeting as summer lightning. The sidhe were riding out to confront their foe, armed with their spears and swords of light and their high, piercing horns. A shiver of anticipation ran down his spine as he got to his feet and crept through the trees, careful not to make any sounds. He heard the trickling of a brook and knew he must be close to the river that ran through Faerie. The Forest House was built of the great trees that grew on either side of it. If he followed the river, he would come to it, sooner or later. The trees were like grim silent sentries as he made his way between them, slipping like a shadow from one to the other. He passed a pool and beside it, saw a piece of shimmering fabric. He bent and touched it, rubbing it between his fingers. It was woven of spider-silk and it was sticky with a sidhe’s pale blood.

He stood up, listening. The goblin rampage had met the warriors of the sidhe and the battle had joined somewhere not far enough away. But nearby, someone was trying very hard not to breathe. He looked up and realized that, of course, any sidhe would’ve sought refuge in a tree. He’d been in Shadow too long, and then banished from both worlds, he thought bitterly, to have forgotten so much. He hoisted himself into the branches, then paused, squinting into the green darkness. Nothing in the trees could be as dangerous as what was roaming on the ground, he thought as he saw a pair of eyes gleaming back. “Who’s that?” he whispered. “Don’t be afraid. I won’t hurt you.”

There was a soft gasp and then another, and a pale face peered out from between the boughs. “Who’re you?” she whispered.

“I’m Timias,” he answered. “Who’re you?”

The girl’s mouth dropped open and for a blink, he was afraid her reaction was to his name. She raised her hand and pointed over his shoulder. He turned to see Macha storming out of the trees.

“Did you see that one? That young one?”

“What about the other one? Did you see the other one? I know that one—I’ve been with him before.”

The voices of her companions blended into a harmonious chorus as they raced here and there to catch the mortal apples. Loriana, the sidhe-king’s daughter, eased herself up and out of the water, heart racing. There was something about the young mortal who’d come crashing so abruptly across the border. He was unlike any other mortal, druid or not, she’d ever met. He was obviously one of the druid-born, of that she had no doubt, for every one of his senses had fully engaged hers. But he smelled so fresh and young, like the first pale shoots of new spring leaves. She shook her damp hair out so that it spread around her shoulders like a silken cloak, while she tried to listen beneath Tatiana and Chrysaliss’s chatter.

There was a lambent energy surging through the air like a barely audible hum. The sound of horns was fading but the scent of Shadow lingered and she wondered what brought her father out to hunt. The sidhe didn’t hunt at night. It was far too dangerous, for at night, the goblins crept out of their lairs below the Forest. They themselves were disobeying by leaving their bowers at night.

She sniffed, delicately sorting through all the competing scents twining through the Forest. There he was, she thought, catching the barest whiff of the boy, ripe as a sun-warmed acorn. She closed her eyes and inhaled, pulling as much of his essence, of his scent, as far and as deep into herself as she could, until she was certain she could find him again. He made her palms tingle and her toes curl.

“Let’s go after them—” Tatiana’s hot breath in her ear made Loriana jump. They pressed against her, their bodies damp and cool, and Loriana could feel the need the mortals had roused.

“There was something strange about him,” said Chrysaliss as she wrapped an arm around Loriana’s waist and combed her fingers through Loriana’s wet hair, twining the silky strands around her fingers into long curls. “Don’t you think he smelled strange?”

“He didn’t smell strange. He smelled young,” Loriana whispered. It was already too late to follow, for she could read his essence fading even now, as the breeze dispersed what was left of him in Faerie into the wind.

“Young…” Tatiana drew a deep breath and closed her eyes, leaning her head back into Loriana’s shoulder, wearing a wide smile as she savored the last of the boy’s scent.

“I’d prefer the other,” said Chrysaliss. “The other one—didn’t you see him? The one who told the young one to ride?” In the fading dusk, her teeth were very white as she smiled and her eyes were very green. “Do you know who he is? I’ve seen him on this side of the border more than once or twice—he’s the first I’d pick at night, too.” The two collapsed on each other in gales of giggles.

Loriana looked up and frowned. The leaves on the trees were quivering and the throb in the air was more palpable. Beneath the branches, the dark pools of shadows began to grow around the trunks. Their bath had been fun, but now it was spoiled somehow and she felt not the slightest desire to get back into the water. “I think we should go home.”

“Why?” Tatiana waded out into the center of the water and peered down into the shallow depths. “You know, if the moon would just rise a bit, I think we could—”

“Tatiana, come back.” Loriana grabbed Chrysaliss by the wrist, as if to prevent her from doing the same. “Come, let’s get out of the water. I think we should go now.”

“But why?” Tatiana flung a few drops of water at them both and grinned. “This stream cuts straight through Shadow. We can follow him, we can find him—and the other one, too. Come, what’s the harm?”

Beneath Loriana’s feet, the ground gave a palpable throb. “What’s that?” asked Chrysaliss, looking down. The throb was growing stronger.

Loriana looked up. The leaves shook visibly and the subtle throb had turned into an audible pulse. “It’s drums,” she whispered. “Goblin drums and they’re not just getting louder, they’re getting closer.”

As if she’d given a signal, a hideous cacophony erupted from somewhere far too close. Chrysaliss wrapped her arms around Loriana, and Tatiana, galvanized, came running out of the water.

The pounding was growing louder. Loriana grabbed for Tatiana’s hand and the three clung to each other. “Which way are they coming?” breathed Tatiana, as they backed up close to the largest of the nearest trees.

The sound was all around them now, shuddering through the ground, rending the air, and Loriana pressed her back against the tree. Up. The word filled her mind with urgency and Loriana looked up. The branches above their heads were bending down. “We have to go up,” Loriana answered as the ground began to quake beneath their feet.

“They’re coming this way,” Loriana said. She reached up, into the welcome of the tree, felt the branch twist itself beneath her hands. The other girls scrambled beside her just as the leading edge of the horde ran across the stream.

The screeches and the screams, the trills and the yelps were all part of some discordant language, she realized, but the drums, so wild and so loud, were disorienting as they filled the air.

“Wait—I’m fall—” cried Tatiana, and she did, slipping off the branch and tumbling to the ground below. She landed with a thump, and as Loriana gazed down in horror, Tatiana was caught up by the goblins. With shrieks of glee at their unexpected prize, they dragged her into their midst, tossing her from one to the other as they ran through the trees.

Her screams faded as the horde swept by. “What should we do?” Chrysaliss whispered.

“Stay here,” Loriana whispered back. The goblins were galloping under the trees now, scrambling like drunken mortals, heady with the noise and the scents. “We’re just going to stay here. And hope they go away.”

“Or that someone finds us.” As if in reassurance, Loriana heard faint, frantic blasts of the horns. “Hear that? Father’s coming.” She squeezed Chrysaliss tight, and the two clung to each other and the trunk of the tree. Loriana pressed her cheek against the papery bark of the ancient birch. But the goblins weren’t going away. They roamed back and forth beneath the trees, pausing every now and then to sniff and peer.

“What’re they doing?” muttered Chrysaliss. “Why don’t they go away?”

“It’s like they’re…like they’re looking for something,” Loriana breathed back. The horns sounded louder, and in the far depths of the wood, Loriana thought she saw distant flashes of the sidhe’s lych-spears. “Or someone.”

“What if they look up?” Chrysaliss whispered. “We should go higher.”

Loriana froze. Like her mother, she despised heights. Beside the squat old birch, its boughs interlaced, a graceful ash soared high.

“Come on,” Chrysaliss was tugging at her, pulling her off the birch and onto the ash. “Come, we have to get higher—higher where they won’t see us—” A clawed hand snaked around her ankle and yanked her down. She disappeared below with a high-pitched scream.

Gasping, Loriana bolted. Across the limbs, light as a wisp, she darted, dashing from branch to branch, following the line of the river that carried her, against all instinct, away from the Forest House. But the horns were louder now, the goblin drums less insistent. She paused to catch her breath in a hollow of a bending willow. The goblin roars were louder, if possible, but she heard the battle trills of the warriors, saw the flashes of light zigzag across the sky like summer lightning. They were fighting somewhere very close, she thought. She curled up as tightly as she could within the hollow, her arms wrapped around her knees, her face tucked down. The sound of her friends’ screaming echoed over and over, and she trembled, bit her lip and tried to stop shaking.

But the smell of burning and wafting smoke choked her and, peering cautiously out, she looked around in all directions. Another noise was rising on the wind, a noise only the sidhe and the trees could hear. It was the screaming of a living tree on fire. Loriana’s gut twisted and nausea rose in the back of her throat. She staggered, clinging to the trunk of the nearest tree, and felt the pain resonate underneath her hand. They all shared it to some degree; they all felt it. And then someone stepped around a tree, a tall figure, pale as a goblin in the sun, carrying what appeared to be something limp and dead.

At first she thought the figure was her father. But it can’t be Father, she thought. But the figure had his walk, his stance, his set of shoulders. Not his hair, for Auberon’s was as copper as her own, and this man’s feathered around his face in coal-black waves, reflecting blue glints in the moonlight. He was mostly naked, but for a pair of torn boots and ragged trews of the kind the mortals wore, and she wondered why he didn’t come up into the trees out of harm’s way like any reasonable sidhe. Intrigued, she watched him as he passed beneath the willow. Swift as a cat she uncurled herself and crept silently just behind him.

He paused, looked up, and seemed to sense her presence. She darted around the trunk as he hoisted himself into the tree. He turned one way, then another, and their eyes met. In the dark, she saw the green gleam of his. “Who’re you?” she whispered.

“I’m Timias,” he replied, and the name made her eyes widen.

This is Timias? Raised by her grandfather, King Allemande, beside her father Auberon, after his own family was slaughtered, Timias was hardly mentioned by anyone at Court, he’d been gone so long. She’d been still a child when he left. He looked like a pale imitation of her father in the starlight.

“Who’re you?”

She opened her mouth to answer, when violent movement in the trees behind him caught her eye. She gasped and pointed over his shoulder as the biggest goblin she had ever seen burst through the trees, running, it seemed, directly at them both.

Timias grabbed her wrist and pulled her up higher into the tree, but not before the goblin spotted them. As the goblin leaped for them both, Loriana saw her mother and a dozen or more mounted sidhe come riding into the clearing. As the sidhe raised their weapons, Loriana clung to Timias’s hand. “What is that thing?”

“That’s Macha, their queen,” he answered. “The sidhe have a king—the goblins have a queen.”

The enormous queen reared up and around, dwarfing the warriors on their dainty white horses.

“And that’s my mother,” Loriana said. She tried to see past him but he wouldn’t let her.

“We have to run,” he said. “Now!”

He dragged Loriana stumbling and weeping through the trees. At last he paused. “I’m sorry if I hurt you.”

“That was my mother,” she whispered, wiping her face. “Leading the warriors, that was my mother.”

She heard the soft intake of his breath. For a long moment, they sat in silence in the dark. Then he said, “You’re Auberon’s daughter, aren’t you?”

She raised her eyes to his. He was staring at her almost the way a goblin would and for a moment she felt a prickle of fear. Don’t be silly, she told herself. He saved your life. “Yes,” she said. “I’m Loriana.”

She expected him to say something, but he ducked his head and said, “We can go lower now, I think.”

Instinctively, she clung to his hand. The palm was wet, the skin was fleshy, but he held her strongly, firmly and she was comforted enough to let him lead her. She could see the lights, hear the shouts of the Court.

“What were you doing out there?” Timias was asking her.

Her lower lip trembled as she looked up at him. “We were bathing,” she said.

“Did no one warn you to stay out of the wood?”

“Of course they did,” said Loriana. “The wood, not the bathing pool by the river.”

He took her by the elbow and pointed. “Look—we cross that stream, we’re there.”

She took a deep breath, forcing herself to follow his voice, to cling to his hand. Her grandmother had nothing good to say of Timias, her father spoke of him seldom if at all. But he’d come back just at the right moment. She thought of her mother and her friends and the other warriors and tears filled her eyes. She followed him blindly, and stumbled against him, not realizing that he’d stopped, for no apparent reason, in the middle of the path.

“What is it—” she began as she peered around him, but the words stopped in her throat. She gulped, blinked, and blinked again, as if she could clear away the nightmarish scene spread before her. The banks of the little stream were pocked with blackened grass, and on it, creatures that oozed whitish substances flopped miserably about. She looked up at the holly tree beside her, wondering why she felt nothing at all from the tree, and realized the tree, and all the others around it, was dead, the berries dull and black amidst the waxy gray leaves. “What did this?” she whispered. “Do you know what happened here?”

To her surprise, Timias nodded, his mouth a straight grim line. “This is what happens when silver falls into Faerie.”