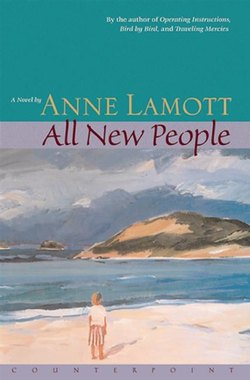

Читать книгу All New People - Anne Lamott - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеI AM LIVING once again in the town where I grew up, having returned here several weeks ago in a state of dull torment for which the Germans probably have a word. There is green, green moss on the bark of the elms we shinnied up as children, when this was a railroad town. A thousand memories have returned in the past few weeks, odd and long forgotten, triggered by the sight of ancient houses, the smells of eucalyptus and the sea. They emerge as in those pictures we made when we were young, where you crayon circles and squares and patches of bright color until no more white paper shows, and then crayon over this with black until no more color shows, and then etch a picture with the tip of a paper clip—but by then you’ve forgotten where you put each original color, so that spidery Miró objects appear: red-violet trees, green horses, blue stars.

An old woman I’ve known all my life, named Angela diGrazia, calls hello from her garden, just across from the little white church on the hill. My brother started a fire in her kitchen wastebasket when he was four. Her old man and my father and the other men in the neighborhood, most of whom worked in the railroad yard, gathered once a year to stomp grapes, from which they brewed potent, battery-acid wine. I can remember her old phone number—GEneva 5-1432—but not her husband’s first name. I wave to her but do not stop, partly because I’m late for my appointment, and partly because our conversation is always the same. First she complains about her back and the gophers, and then exclaims that there’s never been any doubt about my paternity, although in fact there was, on my part. My brother told me every chance he got that mom and dad were not my real parents, and I believed him, partly because no one else in my family but me had wildly curly hair. “I remember the day your parents brought you here to live,” he’d say with an air of wistful reminiscence. “Your mother was wearing yellow pedal pushers. And your father was a Negro.”

Wildflowers bloom on the marshy fingers of earth that run down below the steps of the church. When the hillsides turn brown in the summer, millions of flowers appear in stripes: California poppies, leopard lilies, monkey flowers, buttercups, grass of Parnassus—brilliant white stars—and black jewel flowers. Black jewel flowers are dark garnet red, not known to exist any where else on earth but on these hillsides. You can still see San Francisco, Alcatraz, and Raccoon Strait, but when I was a child, the hills were shaggy and bare. My father took us on walks behind the hills, naming birds for us—juncos, robins, meadowlarks—and one evening at dusk we came upon a gypsy camp, their cars and wagons in a circle. The gypsies showed us small clay nudes—but maybe I’ve made this up. My brother doesn’t remember, and my father has passed away. My brother and I caught tadpoles and frogs in the streams that cut through these hills, and my brother used to bring me to his fort up here behind a cluster of cypress trees, and make me undress for his cronies, who in exchange gave him baseball cards.

The old railroad yard is now the site of offices and condominiums, and I am headed there to see a hypnotist. My mind is an unholy puppet show. It is not on my side, does not have my best interests at heart.

There is the matter of forgetfulness, how in my early thirties I already exhibit a worsening feeblemindedness; and how my mind is full of the forgotten, events that happened long ago and over the years that bred and feed my urbane derangement. And how I have told most of my stories so many times that it has become a way of forgetting.

One thing I know for certain is that my memories are not the same as those of my brother or mother or father; we all have our own version of what really happened, of how it really was. It is a Rashomon history. If you took our four versions and laid them one on top of the other in bands, as they do in sound mixing, you would end up with a song of my family.

I pass the field where we as a town burnt our Christmas trees on Twelfth Night. There would be a hundred trees or so, pine and fir piled like a massive haystack beneath the night sky, moon and stars. Then whoooooosh, it was lit and began to burn fast, really fast, crackling, snapping, with a roar somewhat like the surf, and it smelled like the essence of Christmas, a sharp thick smell like a pungent rain-clean forest, and we hooted and cheered at the roaring wild orange flames in the night.

My best friend all those years was a Catholic girl named Mady White who lived half a mile away, whose family I adored because they said “mann-aize” and “toelit” and “warsh,” and because on Fridays they served tuna-noodle casserole or English muffin pizzas. Mady’s mother wore her hair in a French knot, and you could push her pretty far before she would resort to the universal cry of motherhood, “You go to your room right now, and you go home, Nanny Goodman.” Sometimes she would let us eat popcorn and tomato soup for dinner on Fridays, but unlike my mother she wouldn’t feed the hobos. Once she gave a hobo who came to her door The Power of Positive Thinking. Hobos still arrived in town when I was a child; they’d get on the trains up north, thinking they’d arrive someplace from which they could go someplace else, but our town was the end of the line. So they would come by our houses looking for chores, chopping wood or raking leaves. My own mother would bring them glasses of cold apple cider while they worked, and send them packing with a brown paper bag of salmon salad sandwiches.

My father went to see a hypnotist a year before he died. He and my mother were visiting friends in New York, and one of them recommended hypnosis to help him quit smoking again. “It was truly something,” he wrote to me. “I was half expecting Lon Chaney, Jr., in Inner Sanctum—‘Luke eento my eyes,’ he would say, and then send me forth on a quest for gopher blood or head cheese. But my man looked like a Great Gray Owl, with agate-hard eyes; there was a picture of him and his wife on the wall and you could see that just as the shutter clicks he is saying, ‘No, I won’t miss you, not any of you.’ This look is what I would have expected to discover in the deepest recesses of my soul, but what I found instead was a soft tranquil pool. Afterwards, I went without smoking for nearly an hour.”

My hypnotist is sixty or so, smiling and kind, John Kenneth Galbraith in L. L. Bean clothes. “How are you?” he asks.

“Fine,” I say, and offer as proof a leering rictus of a smile.

His uncluttered desk and chair and the chair beside it, in which I now sit, are the only furniture in his office. On the wall is a print of a Chinese lion, the only decor. One window looks out on the bay, through trees.

“What are you here to work on?” he asks.

“Oh,” I say, “anxiety, melancholia; fears of loss, rejection, death, humiliation, suicide, madness . . .”

He is nodding at me, kind and thoughtful, “Okay, then,” he says, “tell me what your strengths are.”

Squirming, fidgety, I finally allow as to how I can be sort of kind, sort of funny.

“All right then. You’ll need to remember that later.”

“How long is this going to take?”

“Altogether? Maybe a couple of hours. Let’s begin.” He asks me to close my eyes. “Good. Now take a few deep breaths. All right: now think of a color you really love, a color you find soothing, and breathe that color in and out, over and over.”

I settle on chick yellow, inhale it, exhale it.

“Now, while breathing in your color, say to yourself, over and over and over, ‘I am hearing . . . , I am seeing . . . , I am feeling . . . , but fill in the blanks, ‘I am hearing—my voice, I am seeing—black, I am feeling—skeptical, I am hearing—my heart . . .’”

I am hearing my breath, I am seeing spangly black, I am feeling skeptical, hearing the rustle of leaves, seeing my own face, hearing the hypnotist clearing his throat, seeing the sea, feeling hungry, hearing birdsong, seeing our hillsides in winter, Ireland green, feeling relaxed. “Deeper and deeper,” the hypnotist says, “over and over and over.” After a long while, I am aware of an amniotic silence in my head, and then I am aware that I’m on the verge of drooling.

“Now,” he says. “Beginning with today, I want you to go backwards in time, and ferret out the memories of pain: of despair, rejection, terror, shame. Freeze each memory, study it like a photograph, and then go backwards to the next one. Take as much time as you need.”

The first moving slide appears on the screen in my head. I see myself lurching away from the home in Petaluma that I had shared with two couples in love, a home to which I had fled when my marriage broke up, a home so full of romantic gazes that I felt alternately like the lonely innkeeper and the court jester. Climbing down the porch stairs with two heavy suitcases, bolting for my car, consumed with memories of pain, staggering like Gabriela Andersen-Schiess coming around the track in the final lap of the Olympic marathon, where the pain and exertion are so great that they could have caused brain damage. I study this still with absolutely bemused detachment. I go back several months to the end of the marriage, in the ramshackle house on the Petaluma River. The water was so beautiful at sunset it could make your stomach buckle. We lived there for three years, my husband and I. The hills went from green in the winter and spring to golden yellow, Northern California in her blond phase, and the hay grows taller and taller, until you wake up one morning to the sound of the hay-cutting machines, which leave the hay on the ground in drifts, and then the bales appear, neatly stacked, golden blocks. By the end of our marriage we sound like Harold Pinter characters, clipped and malicious but ever genteel. Scenes from our marriage that even this morning sent a sickness rushing up my spine. But now I am blithely reviewing them as though I’m on nitrous oxide, placidly aware of the pain. I see our eventual aggressive indifference, hear our gratuitous lies, realize the great betrayal was being replaced in his heart by his work. Lacking the courage to live a quiet anonymous life, he chases down fame as an artist, and finds it to be a cold, beautiful woman who makes it clear he doesn’t quite deliver, and I am made to pay, over and over again. Unfolding backwards through the years, I finally arrive at the hardest memories of all, the joy of falling in love.

“Backwards, backwards,” says the hypnotist.

I am on Mount Tamalpais, twenty-four years old. A week or so before, I had finally emerged from the grief of losing my father, poking my head tentatively out into the world like the aged Japanese warrior coming out of the forest, desperate to know if the emperor is still in power. In town, I ran into the love of my life, a man with whom I had broken up around the time my father got sick, six months ago. We started talking and joking around, and he invited me along for the ride to Petaluma for cocktails with the couple who were our best friends. They were so happy to see us that we ended up staying for dinner. My lover had never before been so publicly demonstrative with me, and I mentally ran through the reasons I shouldn’t start up with him again, but it was obvious as the evening progressed that he was falling back in love. When we went to leave, the engine of his car caught fire, and we had to spend the night with our friends. Clearly a case of divine intervention—God meant for us to be lovers again. And so I began to relax, and fell in love again. Our friends drove us home late the next morning, but we were all so relieved that my lover and I were back together that we stopped to buy champagne and take-out Chinese food and drove up the mountain for a picnic.

We are sitting on a knoll at the top of the mountain with what looks to be a view of the entire world. Over to the right is the deep-blue Pacific, and hillsides roll down beneath us everywhere you look, ridges and limitless trees, the bay gray-green and peppered with boats, and San Francisco as lovely as Atlantis. My lover appears to be almost sick with love and has never seemed so devoted, and our friends are singing the first lines of “What a Diff’rence a Day Makes” to us, and we’re all looking bashful and goopy. Finally we are walking to the car, and our friends are looking at their watches, and ask us nonchalantly if they can drop both of us off at my lover’s house to save time—they’ve got to get back to Petaluma—and I say Sure, and my lover says No, clearing his throat, and that there’s a bit of a problem, and we all cock our heads nervous-sweetly, and I say, Don’t worry, I won’t stay, I’ll just call a cab from there, and he looks stricken and finally blurts out that a woman is waiting at his house for him. I stand there on the mountain frozen by public disgrace.

I study this slide. Backwards? Backwards then. Except for my father’s illness, I’m mostly seeing a sort of moving police lineup of boyfriends and breakups and the ensuing small breakdowns, and then I see a clip in which my father and I are talking heart-to-heart in his study. It is nighttime and we are sipping whiskey, I am twenty-one and sitting on the floor with my back against the closed door, and he is at his desk. He is trying to talk me out of beginning an affair with the married man on whom I have a crush, and who (as I confide to my father) is after me. You’ve had your married affair, he says, and it took you a year to get over. Didn’t you learn anything at all from the experience? Because, baby, ignorance is curable, stupidity is forever. I hang on his every word. We drink more whiskey and talk. We are so close, cronies, allies, family. He says that the clean thing would be not to sleep with Richard, and that there was happiness in clean. And I’m nodding, suddenly solemn and wise, and promise the both of us to nip this one in the bud. So when I do proceed with the affair, I lie through my teeth to my parents about where I am going at night and who I am seeing. The married man and I have a ball, and there is absolutely no way my parents can find out. Except that one afternoon there was a letter to my parents from the wife. I was met at the front door by my father, who was almost crying as he handed me the letter. My mother came into the hall looking at me with an expression I’d only seen on her face when she was watching Nixon on TV: Liar! Liar!

I study the three of us for a moment. “Backwards,” says the hypnotist.

I see myself at nineteen in love with a man who was not particularly bright, but handsome and streetwise and cool. We had been sleeping together for three weeks or so when my period started, and it started just an hour or so before we went out to celebrate something at a fancy restaurant. I couldn’t bring myself to tell him what was going on. He was not enlightened. He didn’t like the smell or taste of women’s bodies. “This is wonderful,” said the therapist I was seeing at the time, when I called for an emergency consultation. “You’ve always had this disgust toward your own body, and now you’ve found someone you can share that with.” She coached me on how to tell him, urged me to just get it over with, but God, it filled me with so much fear, fear that he would want me to go sleep outside in the hut until it had passed. And all through dinner at this fancy restaurant he made sexy little jokes about what he had in store for me later. I would laugh prettily and try to blurt out the news. I kept trying to tell myself that it was really no big deal, that it was okay to have periods, that it just meant I was a woman, and so on and so on, but I couldn’t get a word out. He insisted that we go home to his house, and we held hands in the car and I tried to blurt out the first few words and I couldn’t, until we were finally in his bedroom. “Oh,” I said. “There’s something I wanted to tell you.” He took off his cuff links and started to pull his shirt off over his head and said to me, “Wait, wait, I want to tell you something first!” I nodded and smiled, waiting.

“Good news!” he said. “Clean sheets!”

Nineteen, eighteen, seventeen. There is lots of sorrow and low self-esteem but I also remember it as having been a time when my family was particularly close: we all fought against Nixon and marched against the war and boycotted lettuce and tried to stem the tide of developers who were building homes for rich people, building shops for tourists. I see myself returning from my only year in college, knowing more then than I ever will again. I spent the year hanging out with other bleeding-heart liberals who worked for McGovern and who would never ever drink Gallo or Coors, unless there was absolutely nothing else around. In my struggle to find out who I am, I take only philosophy and literature courses, reading most of the required books so that I could say I had read them, or because a paper was due, and I develop some rather gross intellectual pretensions. For a while I affect a slight and artsy lisp, and then move on to a scholarly, William F. Buckley stammer. I see myself sitting at my parents’ dinner table telling them about the courses I was taking, and I see my hands near my mouth, gnarled with passion and emphasis, saying something like “The—thuhhh—thuhhh—theeeeee matrix through which we studied Thales of Miletus . . .” and my generous parents somehow manage to keep straight faces as I blather on and on; but after dinner when I’m headed upstairs, I hear them chuckle. I stop on the stairs and slowly turn toward the sound. My mother is saying softly, “The—thuhhh—thuhhh—theee uh matrix,” and I can hear that my father is laughing through his nose. “Dear God,” he says.

I see myself a year earlier, my senior year.

I go to a tiny private high school for rich hippies, although I am neither, and one night at dinner I announce, sighing with poignant resignation, that, after all, the unexamined life is not worth living. My parents smile nicely at me, the same way my cousin Lynnie smiles at me when I complainingly remark that all these cats on Market Street keep asking me for bread. She peers into my face and asks, “They do?”

I look at that girl, at me and my pretensions, and then I see another moment in my senior year.

It is one of those Northern California dappled dawns, pink-blue-gray, and I have taken the early commute ferry across San Francisco Bay. Every morning I stop to pick up my best friend at her apartment on California at Larkin, and we walk to our little hippie high school together. This morning I get into her elevator and am joined on the second floor by a sweet handsome man maybe ten years older than I, who has soft black curly Jewish hair. I think I have seen him before, I think I have had a crush on him many times, or else he just looks like the man who organizes the action at peace marches, who introduces the rock groups on weekends at Golden Gate Park, who performs with the improvisational comedy troupe we go to see every weekend, who taught us how to clean up the beach and shorebirds below Slide Ranch, near Stinson, after the oil spill, who taught us what to say when we manned the phones at Suicide Prevention. We say hello and the door closes and then something comes over him, pain in his face, and he leans against a wall, grimacing, and I see that his knee is in spasm. I ask, can I help, can I help, and he nods and begins to slump to the floor. “I’m having a seizure,” he whispers, and all I can think of doing is grabbing for his tongue so he doesn’t choke to death, but he says, “Sit on me and hold my shoulders down.” So I sit astride him and press his shoulders to the floor, and then he starts moaning and writhing, aroused and leering. “Ahhhhhh!” I shout and leap to my feet, nauseated with shame. I stare at the picture of this moment. I have never mentioned it to a soul.

Even years later I couldn’t bear to think of it, and couldn’t keep it out of my mind. It was one of the wormy memories that made up the House of Horrors ride in my head, where around every corner your cart goes flying into the mouth of the snake, or into the fire. But here I am watching it blithely. “Backwards, backwards,” he says softly and I hear the soft rubbery knock as he taps his pencil eraser on his desk.

I am sixteen and in love with an older man, and it is a cat-brown night in San Francisco. I have told my parents that I am staying overnight with my best friend, but I am at my lover’s apartment, and we have made hash brownies to eat the next day at Golden Gate Park, where Quicksilver and Santana will be playing. My lover is in bed and I am wrapping the brownies in foil, and nibbling at the corners and crumbs, just for the taste of the fudge. Everything is normal and lovely, and both of us fall asleep. Then I’m awake, the room is pitch black, and the cat is on my chest, and when I stroke it, its back is as long as a tunnel, my hand is going off into eternity. I bolt into a sitting position and turn on the light. The bed and the floor don’t exist or maybe they do somewhere way way down below; I’m sitting on an infinite expanse of solid white air. My mouth is so dry that my tongue comes off my palate like Velcro, and I can’t breathe. I’m having a heart attack! I shake my lover awake and try to explain that I’m dying, but I can’t talk right—I sound like an Australian talking through Novocain and Quaaludes.

He drives me to the hospital and we are walking toward the emergency ward. He is grouchy and worried, and finally I realize that I’m just stoned from the brownies. I drop back, and when he turns to find me, I am lurking in the corridor like an egret, and I have to tell him I made a mistake: I’m not really having a heart attack, we can go home. And he looks at me with a hatred bordering on horror. “Ferret them out,” the hypnotist coaches.

I am a sophomore at my hippie high school, where three of our students have died this semester, three out of a hundred and fifty, all three with socialite parents. One jumped from a window on Geary on acid, another walked into the sea, the third OD’d on smack in the student lounge. I am one of the few non-hippies, and my English teacher adores me; he is Bertrand Russell at forty, only funnier, and I live to please and astonish him. He assigned a difficult paper on Moby Dick, and several days later I learned that two of my eight classmates were using the Cliffs Notes, so I cleverly used the Monarch Notes and paraphrased its interpretation into an impassioned, possibly brilliant essay. Three days later, he read it out loud to the class, without saying who had written it, and my classmates cheered when he was done and I squirmed demurely, basking in glory and his approval until I saw him reach into his desk for a copy of the Monarch Notes, heard him read the passages from which I had cribbed my essay. I went brain dead. Rigor mortis set in. Class must have ended at some point because my teacher and I were alone, and he looked sad and guilty. I cannot see what happened next, I really can’t, and so after a minute I go backwards.

I see the day when the last train left town.

My junior high is on the grounds where the dairy farms used to be, and I hate seventh and eighth grade daily but especially the nights when there are dances. I see myself taking it all out on my mother. I see myself punish her with sullen, aggressive laziness. After dinner, when she asks me to take out the garbage or do the dishes, I look at her like she just must be out of her mind. I remain at the table after my brother has gone upstairs to study, and my parents to the living room to read, and I wearily cradle my forehead in the palm of my hand, cursing my fate. Then I get up and carry the dishes past her as if they are limestone blocks for her pyramid.

Seventh- and eighth-grade dances, and gym: I pretend that my periods have started for about six months before they do, doubling over with monthly cramps so painful that I look like a man who has just been kicked in the old gwaggles. And one of the other mothers mentions these cramps to my mother one morning, and when I get home from school that day, my mother is waiting. And I have to discuss the ruse with her, which is all about desperate unhappiness, and I cringe, crying, the entire time.

I want to look and be like everybody else, but I feel so weird, so other. Everybody else wants to look like Jean Shrimpton or Cher, so I get my hair straightened and end up looking like a cross between Herb Alpert and the Shirelles.

Sixth grade is easier to take. Men are tearing down the building that contains the turntable in the railroad yard, the roundhouse where they fixed the locomotives, and they fill in the swamps where we used to raft, and build a Safeway, a ritzy hotel and a B of A. My parents march for civil rights. Our teachers show us Reefer Madness films, and we thoroughly believe the message—a mother walks in on her son smoking dope, and screams as if she had found him hanging from the rafters. Bad people, scabby and drooling, use drugs. So it is with a sense of horrified betrayal that I read an article by my father in which he describes an afternoon spent with his writer friends on a porch in Stinson Beach, drinking red jug wine and smoking marijuana. He has pulled the rug out from under me, and I march into the living room, holding the magazine, glare at my father who is reading a poem to my mother, and say slowly, “Daddy? You have brought shame upon this family.” And he howls.

There is always one problem or another in having a father who is a writer. My brother and I secretly believe he can’t hold down a job. Mady White has an uncle who “can’t hold down a job,” who stays at home all day (like our father) and paints toreadors and clowns on black velvet. I stand outside my father’s study after school and listen with despair as he types. I also listen with despair when my parents fight in their bedroom about things that usually stem from there not being enough money; in my bedroom next to theirs I have to lash myself to a tree and wait for the storm to pass.

The allowance he gives her for groceries never lasts the month, and it is only by hook and by crook that she keeps us fed and clothed. I see her meet me at the door one day after school, in fourth grade: she is holding one of my white Mary Janes, but the strap has been chewed off and the rest is pockmarked with the teeth of our mongrel dog, and my mother is actually begging me not to tell my father—she’s so stricken with guilt that you might have thought she had chewed up the shoe herself. She’s whispering, she’ll buy me another pair with next month’s grocery money, and I am so ashamed of her shame, and so afraid of her fear, that I cross my arms and glare.

The hypnotist coaches me, “Earlier, earlier,” and I look through a hundred migraines, the shame of migraines. Shame is where I live, shame and loss. I got migraines at birthday parties, I got one at the Nutcracker, one at the Grand National. I look through all those hours spent lying still in the dark pierced with white head pain, hallucinating. Once I got one at a movie theater with a family of Christian Scientists and I told my girlfriend, who told her mother. I thought they would take me home, but instead the mother whispered to me to rub my temples in a circular motion, and she showed me how to do it. I tried and I tried as the headache was building, expanding in concentric circles; the girlfriend and her mother both massaged their temples in circular motions along with me, all three of us staring at the screen like the migraine version of the monkey-see, monkey-do monkeys. But finally I had to get up and go into the bathroom and throw up, and then I lay on the floor with my face pressed against the cool tiles, and I kept scooting around on the floor because the tiles under my face would heat up the way pillows do. Then I remember them standing there in the doorway staring down at me, afraid, and that is all I remember. I was in second grade.

I can’t see anything else for a minute—and then I see myself at Girl Scout camp for the summer, when I was seven years old, with a marble-sized growth on my arm, a vaccination reaction, and all of us girls are splashing around happily, whooping it up, when all of a sudden the knobby growth on my arm pops off into the water. The girl beside me screams, and all the little girls head for the shore shrieking, as though someone has spotted a fin.

“Ferret them out, ferret them out.” I woke up from a dream at Mady White’s house in first grade, screaming for my father, a dream in which the streets were wall-to-wall with people, and airplanes were dropping us bundles of food. In real life there was a book on the population explosion on the hamper next to the toilet at our house. My parents had explained what the book was about, and I picked it up all the time, and I’d look at the headlines on the back cover, gasping. I was six years old. In the dream I couldn’t find my parents or my brother in the crowd and I screamed and screamed and woke up everyone in Mady’s family, including the new baby, who cried at the top of her lungs for an hour or so. In the morning everyone was tense and exhausted, especially Mady’s four-year-old asthmatic brother, and I sat there politely at the breakfast table, staring into a bowl of corn flakes, asking in a whisper for someone to please pass the milk.

It is getting hard to remember now. I see scenes of being caught by my parents in lies, or with stolen goods. I see myself with Lynnie in her basement on the day after Easter, doing one of our nudie revues, the dance of the veils—Arabian Nights—wearing only face veils and veil sarongs. We have drawn concentric circles around our nipples to represent belly dancers’ brassieres, and we tantalize the sultan—we whip off our sarongs, little Gypsy Rose Lees, naked as baby birds. Then we hear my uncle, Lynnie’s father, clear his throat. He is in the doorway beside our neighbor John—who goes to Cal and happens to be the man I want to marry—and they are both utterly flabbergasted. We scream and cup our hands over our ballpoint-pen brassieres, and both of us burst into tears. I study the moment, move on.

I think I must be five years old or so, and my brother comes into my room one night, anxious and sad. “They’re coming to take you away tonight,” he says.

“Who is?”

“Your real parents, your mother and father. The Negro.”

“No, no,” I cry. “Hide me! Let me sleep with you tonight!”

He shakes his head wearily. “They’ll only find you,” he says.

I am in Children’s Hospital, not yet four years old, standing in a crib in a ward with nine other children. It is morning and I am talking to my parents, and studying seven black stitches above my right eyebrow, where a cyst was removed while I slept. My parents are beaming with pride. I am feeling very grown-up and sassy, and report to my parents that one of the kids screamed all night, woke us all up, and made us all start crying.

“That was you,” says the nurse.

“No it wasn’t,” I say as if she is an idiot, or lying. And she says yes it was; she had been on duty. The world drops out from underneath me because suddenly I remember standing up in my crib, it is pitch dark and perfectly silent and I am completely disembodied and think I am in outer space, and I scream and scream for my parents. There is a rush of humiliation, a sickening aloneness as my parents try to mollify the agitated nurse.

I stay with this frame for a while. I haven’t thought of it in nearly thirty years. But I’m stuck, can’t go any earlier, and so return to the hospital.

“Are you thinking that you’re there?” asks the hypnotist. I nod. “Are your parents in the memory with you?” Yes. “All right then. We’re going to do a little visualization. I want the adult in you to enter the scene. The adult in you can be funny and kind, you said so before we started. Now go to your parents and thank them for raising you, and explain that you are old enough now to assume responsibility for the child.”

Even in the trance I am filled with derision. This is precisely the sort of thing that gives California a bad name. But I swallow my reservations and walk up to my parents. We do not hug. I stand there shuffling. They look concerned, kind. I am the same age now that they are in this moment. It is too painful to see my father. “Go on,” the hypnotist says.

“All right,” I say out loud. In the dreamy trance I stare at my feet and tell them I won’t need them anymore, that I am going to try to raise this child of theirs. I look up to see that they are nodding and it makes me feel shy and stupid and homesick. “Go to the kid now,” the hypnotist says. “Give her a hand.”

So I walk to the crib and stand beside it and look at the miserable child. Her sad face is screwed up with shame and I want to bolt. It is more than I can stand. Finally, though, I lift her out of the crib and sit down on a nearby chair and hold her in my lap. We sit there rocking. A long time passes; we rock.

“You didn’t do anything wrong,” I say finally, not out loud.

I try to think of things to say that are funny and kind, but all I can do is rock her and stare off into space. “That nurse was a shithead,” I say. “You didn’t do anything wrong.”

“Now,” the hypnotist says. “Play all of your memories forward, all the ones you’ve looked at today, and each time step in to give the younger you a hand.”

So the adult me stepped into my own history, to help, and I went toward the memory of Lynnie and me in the basement doing our nudie revue, and the adult me was funny and kind, snappy, compassionate, there with the kid, saying, “You didn’t do anything wrong,” holding her, teasing her, getting her to relax. Then I went into the lake at Girl Scout camp with all those shrieking girls streaming and splashing out of the water, and I was there standing beside my seven-year-old in the water, making her laugh as I flailed about in mock panic, gaping and gasping at floating pine needles and twigs. And I was there with my eleven-year-old when she felt like a Russian hunchback at the junior high dances, me pointing out a boy whose fly was down and a popular girl dancing with toilet paper stuck to the heel of her shoe; and I was there in high school parties and classrooms, there the day I was caught plagiarizing the Monarch Notes for my paper on Moby Dick. “Hey, babe,” I say to the fifteen-year-old who is cradling her head in her arms, crying soundlessly, alone in the classroom except for the mortified male teacher, “babe, I think maybe this guy didn’t handle this all that well. And what was he doing, big UC Berkeley grad, using Monarch Notes to prepare for his classes?” And I was there with the younger me in bed with all those men, some cold, unfaithful, married, impotent (“Oh dear,” I say to the twenty-year-old when a nearly impotent young lawyer is on top of her, frantically pumping at her, “it’s sort of like he’s doing his push-ups, isn’t it?”). And then I’m there the year my marriage ended in the ramshackle house with cows on the hillsides around us, not able to help very much, just there in the room while she packs, letting her see that I am there, because the worst of it all, time after time, was the utter, abject aloneness. And then the adult me even slipped ghostily into the person sitting there in the hypnotist’s office, like when a double vision slides together into one image, and I sat there for a while feeling sort of old and full of vague yearnings.

I opened my eyes a crack and smiled toward my lap, and suddenly remembered what it feels like to climb the stairs of a New York City subway station, about to go up and outside alone, maybe not knowing exactly where I am, only that I am not completely lost.