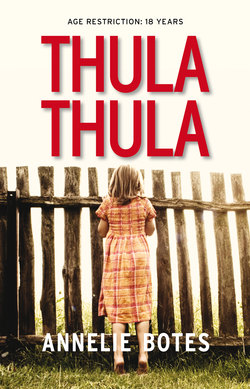

Читать книгу Thula-Thula (English Edition) - Annelie Botes - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Wednesday, 27 August 2008

Оглавление◊◊◊

She stands back to study the sign on the gate, rain dripping from her hair. The sign is green, the capital letters white.

UMBRELLA TREE FARM

GERTRUIDAH STRYDOM

NO ENTRY

TRESPASSERS WILL BE PROSECUTED

The pliers feel cold in her hand. She’s glad she made the sign yesterday and painted it. Put it up as soon as she returned from the funeral in town.

She gathers the cut-off bits of wire and puts them and the pliers in the pocket of her black funeral pants. Walks through the gate and pulls it shut behind her. Slips the loop over the hook. Drapes the chain around the frame and the gate post. She clicks the lock into place, her eyes fixed on her bony hands. They seem older than twenty-six years, an old woman’s hands.

Umbrella Tree Farm. Hers and hers alone. No one will come through the gate without her permission. She wants to be alone. For the greater part of twenty-six years she was nothing, with no say over her boundaries. No place was hers alone except for the stone house she’d built deep in the mountains on the overgrown southern slope. And the corner table behind the maidenhair fern in The Copper Kettle, where she and Braham Fourie used to meet for coffee before she cut him off.

She walks slowly to the house, ignoring the drizzle. Inhales the scent of the lavender hedge that borders the garden path. Even in the late winter the garden is lush, flourishing.

It had always been her job to close the gate and keep the Bonsmara cattle out of her mother’s precious garden. When she was small her father turned it into a game. He’d let her out at the gate, then place a peppermint in her hand as he drove through. She always held out her left hand because her right hand was sticky and stank of piss and rotten fish.

When she was older getting out at the gate and away from him was a release. She no longer held out her hand. ‘Take your peppermint, Gertruidah, it’s your reward for the pleasure along the way.’ She stood like a pillar of salt. ‘If you don’t take it, we’ll melt it inside you tonight and then I will be the one eating it. Are you going to take it …?’

She’d take the peppermint and toss it among the agapanthus beside the gate.

At eighteen, when she was in grade eleven, she got her licence and manipulated him into buying her a car. Then she never went anywhere with him again. On Mondays she drove to boarding school alone, returned alone to the farm on Fridays.

And she never ate anything tasting like peppermint again.

When she was small it took seventy steps to reach the bottom stair. Seventy steps of praying: Gentle Jesus, meek and mild, look upon a little child. The steps became fewer as her legs grew longer. By the time she was seventeen she counted fifty and that’s how it stayed.

It’s been fifty steps for nine years now.

The slate stairway fans out gracefully in the distance, a stone column on either side of the bottom step, each topped with a brown clay pot with gypsy roses spilling out from it. For the first time in her life the stairway holds no terror. Because beyond the stairs, behind the teak front door, there’s no one who can possess her body or penetrate or destroy it. No one to trample her boundaries or make her dance naked in the moonlight. The rider who claimed her for his mare is dead.

Respected Bonsmara farmer. Outrider. Bareback rider. Abel Strydom. Her father.

Ten steps. Another forty and she’ll be there.

Also gone from behind the teak front door, the woman who could turn her hand to anything and ought to have known better than to pretend to be deaf and blind. She’s dead too.

Green-fingered gardener. Stalwart of the Women’s Agricultural Union. Pillar of the community. Sarah Strydom. Her mother.

Fifteen steps. Another thirty-five and she’ll arrive at the stairs.

They died four days ago on their way to the Communion service. An accident on the farm road – Abel was never a man to take his time. Judging by the wreck they’d hit the kudu at full speed, its horn piercing Sarah’s heart and pinning her to the back of her seat.

Abel broke his neck.

When police brought the news she pretended to cry.

This morning she buried them in the town cemetery. She’d refused to have their corpses on her land. ‘Bury them in town,’ she told the undertaker after she identified their bodies on Sunday morning.

‘Gertruidah, your grandmother and brother are both in the family graveyard …’

‘I will decide where they’re buried.’ He raised his hand in protest but she silenced him. ‘I want to finalise the arrangements right now – it’ll be at eleven on Wednesday morning.’

She was dying to get back to the farm. To be on her own, to feel joy, to cry over twenty-two broken years. To reach back into the safety she remembered from when she was a little girl who still believed in fairies and the tooth mouse, before she’d begun to fear the turning of the doorknob at night. ‘Do anything you like, just as long as everything goes smoothly. Tea, cake, ribbons, wreaths, caskets, anything.’

‘At least choose the caskets.’

‘Choose them yourself.’

‘But, Gertruidah, the different styles and prices …’

‘You heard me, you choose.’

A large crowd turned up for the service. She knew what they were whispering to each other: So tragic that the Lord called them so soon. Still only in their fifties, with so much to offer the community. The big question now was who would farm on Umbrella Tree Farm and keep an eye on Gertruidah?

She watched dry-eyed as the caskets were lowered into the ground. All she could think of was the chain and lock she’d buy at the co-op before driving back to the farm. Stop at the store for some food. Don’t forget cough medicine for Mama Thandeka. Sugar and jelly babies for Johnnie.

Twenty steps. Only thirty remain.

At the funeral no one but she knew the truth about Abel and Sarah Strydom. Then she looked up and saw Braham Fourie in the crowd on the far side of the grave, his eyes fixed on her. So there were two people present who knew the truth.

She pretended she hadn’t seen him. Once, in her grade eleven year, she’d allowed him to glance inside her secret room – now, like countless times since then, she regretted it.

Twenty-five steps. The halfway mark.

The funeral-goers scattered flowers onto the caskets. But when the basket with light pink wild chestnut flowers reached her, she demurred. She would not offer them a flower. She locked her fingers behind her back, kept her hands away from the grave. Hands that had been too close to Abel Strydom too many times.

‘Go on, Gertruidah,’ the minister’s wife whispered, ‘take a little flower …’

‘I don’t want to.’

‘Now come on, Gertruidah …’

They all thought she was stupid. They used to whisper that lightning struck beside Sarah’s right foot the day before she was born. That it had made her slow. After a while they grew tired of the lightning story. Then they said she’d never recovered from her brother Anthony’s death. Later still the story went round that she’d been born with a bladder defect.

Covering up, that was all it was. Let the minister’s wife believe what she liked.

‘Maybe a little flower later on, when everyone’s gone …’

‘I won’t want to.’

The woman sighed and moved on with the basket.

Forty steps. Rain drifts down gently onto the slate stairs.

Looking around her she decided it was best if they believed she was stupid. Better stupid than a slut who shared a bed with her father. Who’d believe her if she told them he’d raped and sodomised her for twenty-two years? There she goes again, they’d say, Gertruidah making up silly stories. Because if there was ever a man of impeccable integrity, a man who’d never do that to his daughter, Abel Strydom was that man.

Then she felt someone behind her pressing something into her hands. A wild chestnut flower. When she looked around Braham stood behind her. She dropped the flower, crushed it under her foot.

‘I’ll wait in The Copper Kettle until two.’

She said nothing, looked at him coldly.

‘Let me know if you need me, Gertruidah.’

Fifty steps.

She removes the pliers and bits of wire from her pocket and sits down on the glistening stairs. She hasn’t been inside the house since she came back from the undertaker on Sunday. She didn’t want to feel the lingering breaths of the dead on her skin, or smell their unwashed clothes. She preferred to sleep in the stone house, although the walk there was long and cold and wet.

The sound of frogs in the distance reminds her that before it’s dark she must go tell the river that the graves have been covered and twenty-two years of torture have ended.

She’d ignored Braham Fourie on purpose. She didn’t need his help, doesn’t need any man’s help. Not now, not ever.

She lies down on the bottom step, feels the drizzle carried by the southeaster spray her face. It is cold but healing.

It’s been a while since it rained.

The first drops started to fall just as the minister was crumbling a clod of soil over the caskets. By the time the closing hymn was sung it was pouring. ‘Nearer, my God, to thee, nearer to thee …’ If she’d hated Sarah and Abel less she might have cried. But she couldn’t cry any more. For twenty-two years she steeled herself against feeling. Feeling hurts, and she’s been hurt enough.

It hurts when your father shoves a tin canister up inside you. It hurts when the children at school mock you and say you stink. It hurts giving birth to a child of shame under a full moon. It hurts when Braham Fourie goes to a school function with another woman.

After a while you stop hurting. It’s as if you’ve grown scales on your skin and inside your heart.

She rolls onto her side and supports herself on one elbow, licks the rain from her lips. Her pants cling to her legs, icy cold.

She’s never felt this fearless. Or this directionless at the same time. Her head is swirling, like feeling carsick on a dirt road in summer. Muddled thoughts are all she knows. Being told off for being forgetful or for slipping away into her own world – that is normal.

She was in grade one and Miss Robin was calling to her softly. ‘Gertruidah? Look at me, Gertruidah …’

She didn’t want to be brought back to the classroom where she had to colour in and listen and stand in line. Far better to imagine she was on Umbrella Tree Farm playing among the reeds on the river bank with Bamba. Bamba barked and gulped at the water and chased after the Egyptian geese. She picked a reed and drew a house in the sand. The sand room that was her bedroom had no door. No bed, either. She called Bamba to her and they sat in the sand-house bedroom eating crackers. Dry, because butter turned to snot in her mouth.

‘It’s your turn to read, Gertruidah. Go on,’ Miss Robin said and placed a finger on the first word.

‘I’ll read later.’

The other children laughed. They pinched their noses and with their lips formed silent words so Miss Robin wouldn’t see or hear them. Taunts. She stank, they said, and she was stupid. She wanted to kill them.

‘No, Gertruidah, we’re reading now.’

She dropped her head onto her arms, shut her eyes. She wouldn’t read because she knew the book off by heart. She wanted to go back to the river and her sand-house bedroom. Besides, it felt good when Miss Robin talked to her that way. It made her feel that Miss Robin loved her more than the other grade ones. When she listened, or read when it was her turn, Miss Robin didn’t sit down beside her or rub her back or talk to her in a nice quiet voice. But when she refused to read Miss Robin pleaded with her.

At the end of the year when her report arrived her mother stood in the kitchen and cried so her tears fell into the chocolate cake batter. Because she’d failed.

‘I didn’t fail! I’m clever, Miss Robin said so!’ she tried to argue. ‘We just have to go over the reading books again. Andrea, too, Miss Robin says …’

‘I’m ashamed of you, Gertruidah! You’re a naughty girl! Even Matron complains that you pull your nose up at the hostel food and you wet your bed. You’re a big girl, now, but you behave just like a baby who …’

‘It isn’t true! It’s because there’s a leguan who walks down the corridors at night, I saw him myself, he kills children with his tail and eats them.’

‘Nonsense, Gertruidah! There you go making up stories again! I swear, the next time Matron complains I’m going to buy disposable nappies she can put on you at night …’

She plugged her ears with her fingers and ran out of the house so she wouldn’t hear any more. To the river. She would tell no one about the leguan who left the farm at night to walk to town and enter the hostel. Lying quiet as a mouse in her bed, she could hear his guttural sounds outside the room. Matron said it was the hot water pipes, but Matron lied. She would tell no one she was glad she’d failed because it meant she wouldn’t be with the children who mocked her with their silent words. And if she didn’t want to read Miss Robin would sit down beside her and ask her nicely, please won’t you read. She liked Miss Robin.

One Monday in her second year in grade one she had to go to the school library where a man she’d never seen before asked her to draw pictures and build puzzles and make sums. Miss Robin called him the school psychologist, Mr Noman. She’d never heard of a name like that. How could a man be Noman?

She wasn’t scared that Mr Noman would push his finger up inside her because her mother was there all the time. On the way to town her mother had told her not to say anything about the bed-wetting and the nightmares. ‘You should never talk about things like that, Gertruidah. Not even to your best friend.’

‘I don’t have a best friend. I don’t have any friends at all.’

She often asked her parents if she could invite a classmate home for the weekend. Maybe then at least someone at her school would like her. But her father always said no. If she asked her mother, she said, listen to your father, he’s the head of the house and he knows best.

At night, when she said it hurt, her dad said the same thing, that it was all for her own sake.

She enjoyed her time with the psychology man. She wished Miss Robin could hear how well she read or the way she knew the answer to every sum, straightaway. She wanted to show him how quickly she could build a puzzle but every time he got up from his chair she could see the zipper in his pants, the library smelt of sardines and she’d hear someone rattling the doorknob. Then she couldn’t count or colour in. She lay down on her arms until he sat down again. It was Anthony’s death that had made her this way, her mother told the psychology man.

That was a lie.

She didn’t understand everything her mom told the man but it sounded as if she was on her side. Her mother talked about wanting to protect her child from digging up things unnecessarily, about time healing everything and not wanting her child to become a target.

Target? Was someone trying to shoot at her? And her mother was protecting her – she felt relieved.

They had guests for lunch that Sunday. She sat in the dark beneath the tablecloth in the breakfast nook. Unseen, she could listen to the grown-ups talk. Her mother was sitting at the kitchen table with Andrea’s mom, grating carrots and cutting pineapples into cubes. Her mother was saying the psychologist had said Anthony’s death was the problem.

That was a lie, the man never said that.

Her mother was telling Andrea’s mom a bunch of lies about what the man had said. But she knew he never said it. Never said she shouldn’t drink green or red cooldrink because it would keep her awake at night. Never talked about a bladder infection or her imagination running away with her. And her mother wasn’t saying a word about how well she’d read or that she’d never once coloured outside the lines.

‘Yes, Sarah,’ Andrea’s mom sighed. ‘We’ll never understand how Anthony’s death affected her. She worshipped him. Andrea’s problems are because of a difficult birth. Forceps delivery. Too little oxygen. She was a ten-pound baby, you know.’

She loved words and saved the difficult ones inside her head. Oxygen. Forceps delivery. Ten-pound baby. There were even bigger words she didn’t understand. Allergic, therapy, genetic, trauma, masturbation. It didn’t matter as long as she saved them. At times she took them out, repeated them silently, so only her tongue moved inside her mouth. At night while ugly things were happening inside her bedroom, she said them over and over. Then she forgot a little about the hurt and the sardine smell, she disappeared from her body and turned into someone else.

It felt good to be someone else. Then she wasn’t like Mr Noman who was no one. When she was Allergic Strydom she had transparent wings and could fly right up to the clouds. Therapy Strydom made a little red-and-yellow wooden boat and oars and rowed right past the crocodiles and river monsters all the way to the sea. Genetic Strydom was Goldilocks’s best friend. Together they picked poisonous mushrooms in the forest and fed them to Snow White’s stepmother. Trauma Strydom was a chambermaid who brushed Sleeping Beauty’s hair while she dreamed. Masturbation Strydom always wanted to be the boss. She didn’t like Masturbation Strydom because he hurt her.

Leaning on her elbow she sees smoke curl out of the chimney at Mama Thandeka’s house across the river at the foot of the mountain. They and Johnnie and poor slow-witted Littlejohn are the last people left on Umbrella Tree Farm: the other labourers’ cottages have stood empty for years. Abel always said the new laws made it impossible to employ permanent workers. But Mama Thandeka and Mabel and Johnnie and Littlejohn have life interest, so they’ve stayed.

Johnnie helps in the yard with Sarah’s flowers and the vegetable garden, the chickens and the evening milking. But he’s old and nearing the end of his life. Littlejohn is already in his late forties and the only things he’s good at are eating jelly babies and singing. What would become of him after Johnnie died used to be Abel’s problem. Now it’s hers. Johnnie mustn’t die. He’s more a father to her than Abel ever was. When she was small she’d go with him to fetch eggs every evening. At milking time she’d carry her little mug to the kraal and he’d fill it with warm milk – although later on milk made her stomach turn.

She must take him to the doctor for a check-up, and Mama Thandeka too.

The other labourers who came to the farm were all contract workers. Fencers, pruners, cattle workers, dam-scrapers, soil-diggers. Abel shipped them in as he needed them. Aside from Johnnie it was she who’d been Abel’s right-hand man. There was nothing she couldn’t do. Irrigating, milking, placing salt licks, checking fences, setting traps for the genets. Slaughtering sheep before Abel sold them all. He was being robbed blind and it was cheaper to buy meat at the butcher, he said.

Abel taught her well.

‘We have to keep her busy somehow,’ she’d hear him tell visitors. ‘Seeing as she’s not independent enough to go to university or get a job overseas. But Sarah and I don’t mind, we love her from the bottom of our hearts.’

No one would believe her if she told them how well he’d taught her another kind of manual and physical labour.

Only Mama Thandeka and Mabel knew who Abel and Sarah really were. But no one would believe them either.

At least Mama Thandeka and Mabel had each other and unlike her and Sarah, who were locked in endless battle, they loved each other. She’d be alone in the house from now on. But not lonely. For the greatest part of twenty-six years she’d longed to be alone. To never hear a floorboard creak or a doorknob turn. Maybe the kudu saved her from a prison sentence because she’d been nearing the stage where she would shoot them both in their sleep.

She hears the phone ring inside the house. Let it ring. She doesn’t want to talk to anyone.

She hears the marsh frogs, hears her stomach rumble. She hasn’t eaten anything all day. Not even a cup of tea after the funeral. She’d kept trying to evade the pitying hands rubbing and stroking her upper arms. People touching her made her shudder.

In her haste to put up the sign and lock the gate, she pulled the truck into the shed and left the shopping bag with bread, tomatoes, bully beef, oranges and Tennis biscuits on the front seat. Mama Thandeka’s medicine and Johnnie’s sugar and jelly babies too. She’ll fetch it later.

She wants her own food. The food in the house is dirty. Maybe she should go ask Mama Thandeka for a griddle cake.

Mabel was in a hurry when she came to the yard this morning carrying the laundry basket with wild chestnut flowers. She had to get home, she said, she had dough rising.

‘Is your mother’s chest better, Mabel?’

‘No. Must be rain on the way. Mama started wheezing last night. I was up half the night, rubbing Vicks into her back. You must remember the chest drops, please, there’s less than a quarter bottle left. Raw linseed oil and Turlington too. And Johnnie wants sugar and jelly babies. He says since Littlejohn ran out of sweets the day before yesterday he hasn’t stopped singing “This little light of mine”, not even in his sleep. Says it’s driving him to drink.’

‘Won’t you change your mind about coming to the funeral, Mabel? I’m only leaving at ten, so there’s plenty of time to …’

‘Forget it, Gertruidah. You won’t catch me in the house of our Lord crying false tears for a man I don’t respect. I’m glad I won’t have to put on the face you’ll have to wear today.’

‘Please come.’

‘No. I must fetch wood before the rain starts. I just wanted to pick the flowers to scatter on the coffins, and only because I loved your mother. She taught me a lot.’

‘You’re lucky, Mabel. She never took the trouble to teach me …’

‘That’s a lie, Gertruidah. She gave up because you kept pushing her away. You never wanted to learn anything from her. She taught me,’ and Mabel nudged the basket with her foot, ‘that where too many wild chestnuts bloom you’ll find nothing but false riches. Fat wallets and lean hearts. Your mother was a good woman, Gertruidah, but your father …’

‘At least he had it in him to give you and your mother life interest in your house, and he …’

‘Life interest? Yes, Gertruidah, he did give me life. When Mama was already on the wrong side of forty and he a whipper-snapper of twenty-six. He owes us that life interest, Mama and me. I’m going now. Don’t forget the chest drops and the sugar and jelly babies.’

‘I need a favour, Mabel. Will you go inside the house and bring me my black pants and my white long-sleeved blouse? My black shoes?’

‘Heavens, Gertruidah, can’t you fetch your own clothes?’

‘I don’t want to go inside the house.’

‘So where’ve you been sleeping the last three nights if you didn’t sleep in the house?’

‘You who’s always spying on everyone, you know perfectly well I’ve been sleeping in the stone house. Bring a clean bra and panties too. And my hairbrush.’

‘Heavens, Gertruidah, do you imagine the house is haunted?’

‘No, it isn’t haunted, it stinks.’

‘I cleaned last Friday, what can it stink of already?’

‘It stinks of Abel and Sarah. Won’t you fetch my things for me please?’

Mabel had brought her things. ‘You must wash your hair, Gertruidah. You can’t go to the funeral with it all greasy. I’m going now. You must be strong today.’

At the far end of the lavender hedge Gertruidah caught up with her. ‘Thank you, Mabel. For the flowers. And for …’

Then Mabel reached out her arms. The scent of bruised lavender wrapped itself around them where they stood, half-sisters from the seed of the same man.

‘Drop a bloody big rock on his coffin, Gertruidah, and tell him I say thank you for the life interest.’

She sits upright. Her hands are blue from the cold, her wet pants draw a black outline for her thin body.

Down by the river the frogs have become a massed choir. For years now the river has been her church. After she discovered the Quaker book in the town library she stopped going to church or Sunday school. On Sundays when it was time to leave she’d run away. Then Abel would chase her, catch her and bundle her into the car. On the way there she’d be sick on his best suit. During the service she’d kick and kick against the pew in front of them until Sarah gave her leg a sharp rap. Then she’d cry blue murder while the minister recited the Ten Commandments. Or she’d deliberately pick her nose. Insist on going to the toilet during every service. Cling to the pew in front of her when it was time to split into groups for Sunday school.

She didn’t want to. She wouldn’t. She hated both the church and God. He left her alone in the dark, even if she prayed all night long. He allowed her father to sit in the elders’ pew and made her mother an important woman in the parish. Why didn’t He punish them if He was so clever and could see everything? What was the use of wedging the toe of a shoe underneath her door and asking God to keep it shut? What was the use of telling her mother about the ugly things if Sarah just slapped her shoulder and told her to stop making up stories?

The library book said Quakers didn’t believe in ministers or churches. So maybe being a Quaker was better because being a child of Jesus didn’t help one bit. The book said Quakers just sat quietly and waited; for what, they didn’t know. That was what she wanted to do: sit by the river and wait for the noise inside her head to grow silent. But it never did, it just got more muddled every day.

One sports day at school she went to hide under her father’s truck. She didn’t want to run in the relay race. Her petermouse hurt because the night before her father had wanted to pretend her petermouse was a stew pot and he was cooking a baby marrow in the pot. Then he stirred and stirred the baby marrow. It felt a little nice and a little sore. In the morning when she peed her petermouse stung so badly she pinched off the stream. Now her petermouse itched, and she wouldn’t run in the relay. From underneath the truck she could hear the women talking on a blanket beneath the blackwood tree.

That child’s behaviour must be the bane of Abel and Sarah’s lives, they said. Abel says he can’t chase after her in his best suit every Sunday. It’s easier to leave her with the maid, she’s so disruptive in church. Sarah says she’s safe wandering in the mountains because the Jack Russell looks after her. But I’m not so sure … Here it’s time for the relay and she’s vanished without a trace. What a life she must lead Abel and Sarah. She was such a cute little girl too, but after Anthony was killed she changed overnight …

She didn’t preach to the frogs, just sat on the sand and listened to the voices inside her head. Sometimes they sounded like horses’ hooves or dry leaves. Sometimes she heard a clock ticking inside her head even though there wasn’t one for miles. Then she cried. And cursed. Scrubbed her hands with sand until they stung and she thought at last the smell of fish was gone. Or she wrote words in the sand with a reed and erased them again.

Sharing her words with other people was a struggle because there seemed to be a raw sausage stuck inside her throat. To forget about the sausage and because she didn’t want to be a stew pot, she wrote more words and sentences in the sand.

Erased them.

Wrote.

Erased.

One Friday afternoon after matric she and Braham were sitting at the corner table in The Copper Kettle, hidden behind the maidenhair fern. If the corner table was taken, she waited until the people left. Only the corner table would do. She didn’t want to feel surrounded or trapped, she wanted to sit so she could see the restaurant door. She needed to know where the door was in case she had to escape.

‘People are talking about us, Braham.’

‘In a small town everyone’s always talking about everyone else.’

‘They say you used to be my teacher and you must be crazy to …’

‘Let them say what they like.’ He stroked her knuckles. She yanked her hand away. ‘I want to sit with you. Other people don’t bother me.’

She took the pen out of the plastic bill folder and scribbled on the back of the bill in tiny, barely legible letters. She used only the letters in her name. Tired. Gathered. Tirade. Drag. Tried. Daughter. True. It was an escape. She crossed out every word after it was written.

‘Gertruidah, if you’re not wiping the table with a napkin ten times over, you’re writing on the bill. Look at me, Gertruidah …’

He placed a finger below her chin to tilt her face towards his.

‘Don’t touch me, Braham.’ She pushed his hand away. ‘You know it gives me the creeps.’

‘Let me see what you’re writing.’

She pushed the bill towards him; nothing on it was legible.

‘What is written underneath the ink, Gertruidah?’

‘That I want to love you.’

‘Then love me, won’t you? Come with me to the hospital fundraising dance next Friday night.’

She crumpled the napkin into a tiny ball; wiped the table again. His hand on her wrist. She felt her bladder contract from the shock and tickle. She hated feeling the tickle in her bladder. ‘I don’t own a dress. I can’t dance. And I’ll run away if I have someone so close to me an entire evening.’

‘Where do you want to run to, Gertruidah, and why?’

‘I’ll never stop running.’ With a toothpick she drew circles on the table. ‘I have to go, Braham. My father’s waiting for the lawn-mower blade and it’s almost milking time.’

She placed the right amount inside the plastic bill folder but he took out the notes and held them out to her. ‘It’s my turn to pay. Won’t you stay a little longer, please?’

‘Not today. And I won’t come to town next Friday so don’t wait for me.’

She slipped the notes underneath the vase with wild chestnut flowers. Once on the dirt road she wound up the window to keep out the swirling dust. She seemed to be sitting on something slimy, something that seeped out of her lower body over which she had no control. She beat her hands against the steering wheel, her voice echoing around the cabin. Abel Strydom, what have you done to me! What are you still doing to me! I wish you’d die! I wish I was dead!

The next time they met at The Copper Kettle she wrote on the plastic tablecloth with her finger so her words remained a mystery to Braham.

The first letter she learned to write was A. For Anthony. It looked like a house with a high-pitched roof and no chimney. She used to see it on Anthony’s school books on weekends when he was home from boarding school. Anthony didn’t mind if she paged through his school books. He was six years older than her. He and Mabel were in the same grade but he went to the town school while Mabel went to Auntie Margie’s farm school on Sweetwater. Coloured children weren’t allowed at the town school until 1992, and by then Anthony had been dead seven years. Mabel became Gertruidah’s guardian angel both in the hostel and at school. Because Mabel could always be counted on to fight for her.

Leave Gertruidah alone, you bitch, or I’ll smash your face in!

What, you hit me, you bloody common kitchen maid? That Friday Mabel sat detention because she’d called the white child a bitch. And the white child went home although she’d called Mabel a common kitchen maid.

There were many incidents like this, but Mabel always stood her ground.

She was four and Anthony ten when he died. All she remembers about the funeral is a sheet of paper with light purple Jesus hands, and the A in his name just below them. She knows she must stop brooding about Anthony; he’s been dead for over twenty-two years. She never even really knew him. All she knew was the sense of disillusionment that covered Umbrella Tree Farm like a dark blanket after he was dead.

Still, she sometimes dreams about him with disturbing clarity. Dreams about the tiny birthmark on his forearm or the time his toenail fell off after his toe got caught in the mouse trap; dreams about a birthday cake shaped like a tractor, with the icing in John Deere green and yellow. When she wakes up, her eyelashes are wet and her heart heavy. But even in the wasteland of her most distant memory she knows it’s not Anthony she’s sad about. She’s sad about something inside herself.

No one ever told her how Anthony died. But she heard all about it all the same, whenever Abel and Sarah fought. Especially if Abel was drunk. He was seldom drunk out of his mind but when he was, he was uncontrollable, mad. His rage lasted until it gave way to sorrow; only then would he grow calm.

No matter how it started, every fight ended up being about Anthony’s death, which was why she knew far more than they realised.

Stupid Gertruidah.

If they only knew how clever she was.

The rain has gone; the wind has died down. The mountainside lies wrapped in a thin skin of fog. Aside from the frogs there’s a holy silence, as if the earth is holding its breath. The smoke has gone at Mama Thandeka’s house.

She walks to the shed to fetch the shopping from the truck. Water sloshes inside her shoes and her funeral blouse clings to her breasts. She won’t take the food inside the house. She’ll store it on the shady side of the water tank and cut the bread with her penknife. The penknife has often come to her rescue in the veld.

Her father brought the knife back from an agricultural tour to Switzerland in 1992, when she was in grade four. The date is written under the flap of the leather pouch. It was the same year she asked her teacher if she could take the class’s dictionary back to the hostel for the afternoon. She wanted to look up the meanings of allergy, therapy, genetic, trauma and masturbation because they’d been milling around her head for so long.

‘Why are you looking for those words, Gertruidah?’ the teacher had asked, her eyes wide.

‘Because.’

‘Don’t lie to me, Gertruidah, why those words?’

‘I dreamed about them.’

She could tell the teacher wasn’t going to leave it at that but she didn’t want to talk – her dad said she mustn’t talk. So she imagined there was a slime sausage in her throat and threw up on the teacher’s feet. Throwing up was easy if you thought of a slime sausage. Then the teacher got all concerned about you and let you have your way. Someone being concerned about you felt good. Being allowed to take the dictionary to the hostel made you seem important.

Allergy. Sensitivity to allergens.

Therapy. Treatment for illnesses, disorders.

Genetic. Regarding the genesis of something.

Trauma. Injury, scar.

Masturbation. Sexual self-gratification.

She understood little of it. It made her think of when her father branded the Bonsmaras. Although she felt sorry for the cattle she wished she were a cow so she wouldn’t have to sleep in her bedroom at night. The mark from a branding iron healed after a while but the things that took place in her bedroom made her sick.

When she opens the door of the truck, the smell of oranges hits her nose. She feels light-headed from hunger, and from thinking in circles, calling up images of the past. From uncertainty over whether the things she remembered were the truth. Could they have happened differently, or in a different order? How was she able to retain such big words for such a long time? Could she really read when she went to school? Was her memory shaped by a child’s understanding or had she coloured in her childhood with the knowledge, insight and skills of an adult?

What difference does it make, the when and where? Because nothing and no one can clear the fog of memory from her mind. The fright things. The night things. Moving shadows like tree branches against the dull curtains of her most distant memory. Or like giant hands. Sometimes there are smells and sounds. Could she have imagined it all?

No. Thinking that she was imagining things was what her parents had wanted her to believe.

Despite being washed by rain her arms feel dirty where the people at the funeral tea touched her. When she places the shopping bag on the base of the water tank, the phone rings again. What if it is Braham? She remembers his whispered words beside the grave: Let me know if you need me …

She needs him.

She doesn’t want to need him.

She takes the Victorinox from her pocket and polishes the red handle until it shines.

The year she got the Victorinox was also the year her mother dragged her out of the church one Sunday and gave her a hiding outside because she’d sung ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ so loudly. She never looked in the hymn book because to sing from the same book she’d have to stand close to her mother. She didn’t like her mother. It was better to keep all the hymns inside your head so you didn’t have to stand close to your mother.

Then her mother took her outside and said she was mocking the Lord if she sang ‘Polly shine your boots and shoes’. She hadn’t done it on purpose. It was what she’d heard the grown-ups sing. From then on whenever they sang ‘All Things Bright and Beautiful’ she ran away to Umbrella Tree Farm in her head, to sit by the river and talk to the creatures great and small.

The next September when her mother’s twin sister Auntie Lyla came to visit she brought her a hymn book of her own. She liked having her own hymn book. She liked reading the words herself, and not having to stand close to her mother.

She was thrilled about her Victorinox with the red handle and the black leather pouch she could hang from her waistband.

‘Come,’ her father said, ‘sit on my knee then I’ll show you what the knife can do. The Swiss are master knife-makers. This one is called a Victorinox. Over here!’ He slapped his knee as if she was a dog and he was ordering her to jump up against him. ‘No one at school will have an expensive Swiss army knife like yours.’

She didn’t want to sit on his knee. Didn’t want to!

But the red-handled knife was beautiful; she’d wanted a penknife forever.

And she only had to sit for ten minutes, even though it was bad. During the day, when the sun shone and someone might be around to see what her father was doing, it was different from the night. At night she didn’t sit on his knees; at night she knelt on hers.

At night she shouted, ‘Ouch!’ Loudly, so that her mother might hear. ‘Ouch!’ It stung where he slapped her bare hip and told her to be quiet. He said it was the place where her babies would come out one day and he had to make the hole bigger or her babies would get stuck inside her tummy. He said it was a father’s duty.

But she didn’t want to have any babies, ever. She didn’t want the hole to be bigger. She wanted Bamba to curl up at her feet, wanted her Lulu doll in her arms, wanted her mother to hear when she called. But no one cared what she wanted. No one knocked before they came into her room, and she wasn’t allowed a key. It was different at the hostel where you had to knock before going into someone’s room and you had a key for your locker in the study hall.

Her father said she couldn’t have a key for her bedroom. Her mother said her father knew best, but she knew she was lying. And her father lied too, but you couldn’t tell grown-ups they were lying.

‘Ouch!’ she screamed into the mattress.

Screaming didn’t help. No one heard.

She turned into Sleeping Beauty, asleep for one hundred years. And because the castle was overgrown with rambling roses covered in thorns, no one could come near her. She wasn’t Gertruidah Strydom: she was a sleeping princess on a featherbed. In her sleep, even though she wasn’t asleep, she drew a picture of the prince who would break through the rose thorns to wake her with a kiss.

When Braham Fourie joined the school as English teacher in her grade ten year, she couldn’t tell right away he was a prince.

After a while she forgot the ten minutes of knee-sitting. Forgot how the waistband of her shorts cut into the flesh of her abdomen as it was pulled tight from behind. Knuckles drilling against her tail bone as he wormed his hand inside. She no longer heard the panting in her neck. No longer felt his body jerk or the final bump, bump, bump against her back. She scraped the back of her shorts against the stoep wall to remove the rope of slime. Took Lulu down to the river; hugged her against her chest. ‘Thula thu, thula baba thula sana,’ she sang the song Mama Thandeka had taught her.

Ten minutes was nothing.

Your Victorinox lasted forever.

She imagined the day she would turn into a baboon that lived in the mountains, with no doors or walls. Then she would take her penknife with her. She could use her Swiss army knife to peel prickly pears in the veld, or to skin a porcupine if she were giddy with hunger. It had a screwdriver, bottle opener, ballpoint pen and toothpick. Tiny pliers for removing thorns. A ruler and a compass so you wouldn’t lose your way when fog rolled down the mountainside and you couldn’t see your hand in front of you. On one end of the ruler, a tiny magnifying glass to start a fire if you ran out of matches or they were wet. A torch the size of her little finger she could shine into Bamba’s eyes at night to check that he was alive.

It was her father who brought and gave her the knife. With love.

Abel who showed her how the knife worked while she was sitting on his knee. Also with love.

The difference between her father and Abel was as wide as a ravine.

And love was something she would never understand.

The maidenhair fern in The Copper Kettle was her witness that she told Braham: ‘I have no idea how to be good to you, ever. Because I don’t know what goodness is.’

Her stomach rumbles again. She hasn’t eaten anything since yesterday when Mama Thandeka sent Mabel with an enamel dish with mealie rice and curried potatoes and chicken livers. Mabel wanted to clean the house and do the laundry. But she sent Mabel home.

‘There’s nothing to do here, Mabel. Rather go …’

‘What about the laundry? There must be a bundle of sheets, I haven’t changed the beds since last Wednesday.’

‘Mabel, after the funeral tomorrow I’m going to burn the sheets.’

‘Heavens, Gertruidah, they’re good sheets! You can’t go and burn them, rather let me and Mama take them.’

‘I’ll buy you new ones. I don’t want their bedding here on Umbrella Tree Farm. Now go wash and braid your mother’s hair. You were going to do it on Sunday before the police came and everything got muddled …’

‘At least let me sweep the stoep and rinse out the milk cloths, and …’

‘There are no dirty milk cloths here. Now go, I want to make a sign for the gate. Tell your mother I said thank you for the food.’

‘What sign are you making for the gate?’

‘You’ll see when it’s done.’

After Mabel left she ate with her fingers. Drank water. Went to the shed to cut the sign out of a windmill fin. Gave it a coat of green tennis-court paint. The white paint for the lines she used to paint the words on the green background. Used the wool bale stencil to make even letters. Who would have thought Abel’s tennis-court paint would one day be used to keep people away from Umbrella Tree Farm. Who would have thought that one day she would make the rules, or that the tennis-court paint would be hers to mess with any way she liked.

The terribly important tennis court.

You needed an invitation to play. An invitation meant you were part of the elite who played social tennis on Umbrella Tree Farm on Saturdays, even if you could barely hold a racket.

When she was small, before she got her Victorinox, she used to pick up the balls people hit over the fence. Then they’d say, in voices dripping with condescension: Clever girl, Gertruidah! Just as though picking up balls wasn’t something she was quite capable of doing.

She remembers the last day she picked up balls for the grown-ups. She’d been waiting on the bench beneath the cedar tree for a ball to fly across the fence. Andrea’s mom, who was the magistrate’s wife and ran the tombola table at the church bazaar, rushed, breasts wobbling, to the net to meet a drop shot. She crashed into the net and hung doubled over the tape like a pillowcase on a washing line. Before she could straighten up, her stomach went. Pale brown liquid soaked her frilly pants and ran down her legs into her socks. The bubbling noises could be heard all the way to the cedar tree.

She laughed, she couldn’t help it. She’d never seen someone poo on a tennis court before.

The magistrate’s wife was crying; someone rushed over with a towel. Then, because she’d laughed, her mother dragged her into the lapa and beat her with a tennis shoe. She was rude, her mother said, and she was ashamed of her. Sarah pulled her ears too, because she’d hidden her Lulu doll away so Andrea couldn’t play with her.

‘You selfish child! It’s just a bloody doll! Why won’t you let Andrea …?’

But it wasn’t just a doll. It was her child.

She never picked up the grown-ups’ balls after that. From then on, on tennis days she and Bamba went to the veld. Bamba chased everything that moved: field rats, dassies, guinea fowl, lizards. A Jack Russell will even chase a jackal or a lynx and never give up, panting, like other dogs. Mama Thandeka had told her Bamba meant ‘catch’ in the Xhosa language; it was the name Anthony had given him. Bamba had been Anthony’s dog. When Anthony died, he became hers.

Bamba wasn’t allowed near the tennis court because he ran up and down along the fence and barked. If he wasn’t allowed there, she would stay away too.

When she was older her father tried hard to teach her to play tennis. Her clumsiness was just a pretence. She didn’t want to play tennis. She didn’t want to bend down in front of him wearing a short tennis dress so he could stare at her bare legs.

She only started playing in grade ten when Braham Fourie became the school’s tennis coach.

She began to feel sorry for Andrea the day her mom crapped herself on the tennis court. Her eyes always seemed wet with tears and she was fat. Gertruidah knew, without knowing how she knew, that Andrea’s mom took laxatives, just like Sarah. She’d sometimes seen the empty bottle in the bin in the bathroom. Each tablet contained Bisacodyl 5.0 mg, the label said. She didn’t know what it meant. But she knew she would when she was older. Just like one day she’d know the meaning of all the grown-up words she’d stored inside her head.

Maybe her mother was afraid her own stomach would go on the court, maybe that was the reason she didn’t play. On Fridays she cooked for Saturday’s tennis. Nibbling constantly. Egg mayonnaise. A bit of puff pastry. Salami. Ox tongue. Glacé cherries. As long as she kept taking laxatives, she wouldn’t get fat. Along with crossword puzzles, cooking was Sarah’s gift. Whenever Abel bragged about her food or the set of cast-iron garden furniture she’d won with a crossword, Sarah blushed.

Abel was a skilful player. Agile, tactical. He shone at the net and used his height to advantage. He was a gallant host, too, because on Saturdays when there was tennis he didn’t drink. On Sunday he would have to lead the hymns in church and he always said he couldn’t take the lead in the Lord’s house with a hangover.

Thinking about it makes her feel sick. How could the same man who led the hymns in church make her sit on his knees with the Victorinox? How could he use the same throat for praising the Lord and for panting behind her shoulder blades like a tired dog?

And yet.

In primary school, on Saturdays when she and Bamba didn’t go to the veld or if they were home early, she’d sit on the stoep wall and watch him serve in the distance, watch him move up swiftly to the net. Then she loved him, she didn’t know why, perhaps because with other people around she felt safe. She liked the way he looked in his tennis clothes. They were a different white from the white of his skin. Some nights when he came into her room she imagined he was wearing his tennis clothes; that it wasn’t him beside her bed.

Then she would become Sleeping Beauty.

The sting of the spinning wheel needle would fade away.

The drop of blood disappear.

She was asleep in a castle in a land far, far away, on sheets of the purest white. While she was Sleeping Beauty, everything stood still. Even the king and the queen turned into statues. Nothing stirred – not the steam rising from the plates of food, the flames in the fireplace or the palace curtains. Sleeping Beauty slept and waited for the prince to wake her with a kiss.

She waited a very long time.

By this morning the paint on the sign was dry and she drilled holes in the corners so she could put it up when she returned from the funeral. From today onwards no one will ever possess her body again or have a say about what she does on her own farm. No one but she will fasten the lock and no one but she will open it.

NO ENTRY

TRESPASSERS WILL BE PROSECUTED

She sits down on the base of the water tank. With her Victorinox she slices the tomato and opens the can of bully beef. The phone rings again. She doesn’t want to talk to anyone. Even less go inside the house. Her cellphone is in the truck, its battery flat. She doesn’t care.

The clouds have gone and the late afternoon sun washes the fog on the mountain in light pink. It’ll be milking time as soon as she’s done eating. She’s told Johnnie until the rain stops she’ll take care of the milking herself.

She stows the remaining food inside the shopping bag, grabs a handful of Tennis biscuits and walks to the kraal to milk Freesia. She plans to pour out half the milk for the chickens and take the rest to Mama Thandeka and Mabel. There’s no need to keep milk in the house: she doesn’t touch anything that’s whitish and wet. Milk, maize porridge, cheesecake, white sauce, cream, floury apples, yoghurt, cottage cheese. Gertruidah has to be the only child in the world who throws up if she eats ice cream, she once heard one of the tennis women tell her mother. Sarah had laughed: Gertruidah was just fussy.

Licking an ice cream cone was the worst thing in the world, she’d wanted to say – but didn’t, because it wasn’t true. There were worse things. The smell of a sardine sandwich. Watching her father suck the marrow from the bone in the Sunday roast. Raw egg white. Standing on a slug and feeling the gluey slime between your toes.

And the worst thing of all, the thing she couldn’t tell anyone about.

It was best to say nothing. Then there’d never come a day when you had to drop your gaze before Braham’s at the table behind the maidenhair fern.

Freesia lows when she enters the kraal carrying the milk bucket and stool. The white spots on her Friesian hide are tinted pink by the evening light. ‘I’ve missed you, Freesia. I have a lot to tell you.’

She cannot talk to people, only to cows and frogs and to Bamba. They will never betray her.

When she’s done milking and puts the bucket aside, Freesia playfully nudges her. That means she’s itching. Or perhaps it’s her way of saying goodnight.

Did anyone ever tuck her in and wish her goodnight, sleep tight? It doesn’t seem possible. And yet she has a memory of her mother lying beside her at bedtime and, sometimes, Anthony in his striped pyjamas on the end of the bed. Lying in the crook of her mother’s arm and looking at pictures of pumpkin coaches and a shoe full of children while her mother read. She remembers the scent of her mother’s powder and that lying in her arm had felt good.

But perhaps she remembers wrong.

Had being powerless against Abel been an illusion? Had feeling powerless been an escape or had she been programmed to believe sex with your father was normal? Vaguely she remembers bathing with him when she was small. He’d build a tower of bath foam on top of her head and they’d laugh so much her mother would come to see what was the matter. Him washing her tiny body, everywhere, without it seeming wrong. Falling asleep in his lap while he cleaned her fingernails with his penknife. Being carried to bed and kissed goodnight. No nightmares while she slept.

Sometimes she played a wedding game under the wild olive tree. She wore her mother’s high-heeled shoes and her father was the make-believe groom. She’d marry him some day, she said. He laughed and tossed her high up into the air. Brought her berries and sour figs after he’d spent two days in the mountains looking for cattle.

Then Anthony died; her mother went away to the Women’s Agricultural Union conference and everything turned bad. Back then she believed the things fathers did were right because they were fathers. That all fathers turned the doorknob at night. That it was part of loving, like picking you up and giving you a piggyback and playing catch in the yard.

And yet she never talked about it with other little girls.

Are you born with the knowledge that something is wrong even if you don’t know?

She recalls a Friday. Leap year, 2008.

In her shirt pocket, Grandma Strydom’s ruby ring, brought out of its hiding place in the cake tin in the stone house. In her mind she moved the vase with wild chestnut flowers aside and reached her hands out to Braham. It is leap year, she said, will you marry me? A thousand times she heard him say, let’s go to the magistrate’s office right now.

Dreams. Dreams of travelling to France, to the Saint Claire Church in Avignon to visit the chimera of a fourteenth-century poet. It had been Braham who introduced her to Francesco Petrarca. Dreams of turning Umbrella Tree Farm into a prickly-pear farm. Of travelling to Yorkshire to sit at the grave where the poet Sylvia Plath’s journey ended. Of being wheeled into a hospital theatre for an operation to repair her weakened sphincter muscle. Of playing in the final on Wimbledon’s Centre Court and winning. Of marrying Braham.

Without dreams, no matter how far-fetched, she would’ve ceased living long ago. Simply collapsed and died. Dreams carried her away from the horrors.

Her mother’s voice telling guests: Gertruidah exists in an imaginary world and, what is worse, she believes the things she makes up. I can’t bear to think what’ll happen to her when Abel and I are no longer there …

Leap year, 2008. She recalls the swampy February afternoon heat when she got out of her air-conditioned car outside The Copper Kettle. Braham’s car was already there. She was tired. All week long Abel had taunted her with a toy he’d ordered from America on the Internet. A black rubber thing, covered with tiny tentacles. Repulsive.

‘Get some KY jelly when you go to town,’ he’d ordered the night before. ‘Batteries too.’

She would kill him, she swore. ‘Get it yourself.’

He got angry and shoved the rubber thing up inside her. She pressed her face into the mattress and became someone else. A faceless woman on a train to Avignon. Through the train window she watched the vineyards and linden trees covered with tiny yellow-green flowers slip by. She must take a jar of linden honey back home for Braham. Because he was the sweetest thing in her life.

When the faceless woman got off the train, she heard the bedroom door close.

She stood under the shower to wash away the mess. But the water couldn’t reach inside her unclean heart.

Braham would detest her if he knew. When he left her bedroom at night did Abel detest her too?

‘Hi, Braham. Sorry I’m late.’ She slid into her chair behind the maidenhair fern. ‘I had to go to the co-op for teat salve and laying mash. And there’s my mother’s endless shopping list …’

‘I’m glad you’re here. You mustn’t turn off your cellphone …’

‘I must.’ She took the menu from the waitress. ‘Or my father will keep calling about more stuff to get. White grape juice for me, thank you.’ She passed the menu to Braham who ordered a banana milkshake.

‘So, what was your week like on Umbrella Tree Farm?’

‘Terrible. Farming with my father is misery. Don’t ask why.’

‘I’m never allowed to ask why. You’re a mystery, Gertruidah.’

The ceiling fan hummed; she rearranged the sachets in the sugar bowl. Fingered the tiny bulge Grandma Strydom’s ruby ring made in her shirt pocket.

Moments later she shuddered when he slurped up the thick yellow milkshake. They hardly talked because her sense of her own filth choked the words back down her throat.

The afternoon turned out empty.

Leap year turned out to be just another day.

She fetches the flat rock she keeps on the kraal wall and rubs Freesia’s shoulders and back. All the way down to the rump, the haunches. Ribs, flanks, the curve of her stomach. Down, still further down. Then she puts down the rock and continues scratching Freesia’s stomach with her fingernails. The cow grunts.

‘I know you don’t like it when I scratch your legs and head, Freesia. And you don’t like having your teats pulled, I know.’ She picks up the milk stool and carries it round to the other side. Rubs. Scratches. ‘The funeral is over, Freesia. Umbrella Tree Farm belongs to me now. Here, have your biscuits …’ The cow eats the biscuits out of her hand. ‘Tomorrow I’ll clean your pen; it looks as if the rain has gone.’

She pours half the milk into a bucket for Mama Thandeka. It’ll be dark soon and it’s a long walk to the stone house. The chickens make low gurgling sounds when she pours the rest of the milk into the tractor tyre. Tomorrow they’ll peck holes in the sour white mess.

When she turns around to rinse the bucket under the tap, she sees Mabel standing at the entrance of the coop, holding a bread cloth tied with a knot. ‘Here, Mabel, take the milk.’

‘Wait, Gertruidah, I have something to say. Mama’s chest is better. I’ll come sleep in the house with you tonight if you’re scared. You don’t have to crawl inside a hole like a fox.’

‘I’m not scared and I don’t crawl inside a hole. The stone house is my home.’

‘The veld is wet, Gertruidah. And it doesn’t matter what sort of people your father and mother were, you must have had a bad shock. It’s not every day you bury your father and mother. Let me come stay with you, please?’

‘Then you’ll have to sleep in the stone house too. I’m not spending the night in this house until I’m done cleaning it.’

‘Then I’ll come help you tomorrow morning. But there are things you must tell me before I can close my eyes tonight.’

‘Then ask, it’s getting dark.’

‘Who’s going to take care of things on Umbrella Tree Farm from now on? Because you can say what you like about your father, he was a hard worker and he knew a thing or two about farming. And I want to know what’s the meaning of the sign on the gate. And how long you plan to keep sleeping in the stone house.’

‘Mabel, I want to clean the house on my own. Except for the little jobs Johnnie must come and do, I don’t want anyone in the yard. I will come and tell you when I’m done. Then you and I and Johnnie will run the farm. There’s nothing here we can’t do. For dipping and weaning the calves and the big jobs in the garden we’ll get contract workers. The sign means I don’t want anyone on my land without permission. You must stick to the short-cut through the lucerne paddock. If I catch you climbing over the gate I’ll shoot you.’

Mabel laughs. ‘You won’t shoot me, Gertruidah.’

‘Don’t test me. I’ll probably sleep in the stone house until Sunday night, or else in the truck in the shed.’

Mabel holds out the griddle cakes, tied up in the bread cloth. ‘Mama sends these. Every mealtime until Sunday I’ll leave food at the kissing gate in the lucerne paddock, under the umbrella tree. Take it or leave it, it’s up to you.’

‘Thank you, Mabel. You can fetch Johnnie’s things and your mother’s medicine from the shopping bag at the water tank.’

‘Johnnie will be glad. He’s been peeling resin from the trees for Littlejohn, because that child is impossible without his jelly babies. He’s been singing right through the night: “Someone’s in the kitchen with Dina, someone’s in the kitchen I know, I know, playing the old banjo …”’

‘Do you realise he’s already in his forties, Mabel? How are we going to take care of him if Johnnie dies?’

‘Lord knows but I’m not going to be the one looking after him. And another thing: When are you going to turn your cellphone on? The teacher has been calling me to ask about you. I told him you’re at the stone house and I don’t know when you’re coming back.’

‘Tell him to stop bothering you.’

‘Heavens, Gertruidah, his heart wants you. He’s a good man …’

‘I never want a man near me again. Let alone in my bed. Now go.’

She watches as Mabel walks away towards the shed. Stands with her middle finger hooked through the knot in the bread cloth. Closes her eyes. Sees the letters in her name slide past.

G E R T R U I D A H

The habit of many years, of stringing words into sentences using only the letters in her name, makes the words slip out.

Did Gertruidah guide the dart? Dare Gertruidah trade her heart? Dear Gertruidah tried.

She must stop making up words. There are things she has to think about.

She rinses the bucket and tips it over the coop tap. It’s too late now to walk to the stone house: darkness will overtake her. You should never underestimate the fog. It sneaks up on you like a thief and makes you lose your way. She washes her hands and face at the water tank, rinses out her mouth. Stows the bread cloth with griddle cakes inside the shopping bag. Places a rock on one corner of the bag so it won’t blow away. Walks down to the river to tell the frogs and the water that the funeral is over.

By the time she’s back it’s ten past eight. She strips off the wet funeral clothes and hooks them over a nail in the shed wall. Puts on the overall she was wearing when she painted the sign the day before. Over it, her parka jacket that was lying in the truck. Crumples up a hessian bag for a pillow and lies down on the seat of the truck.

Tired Gertruidah retired at eight. Dare the dead rider hurt her here?

Thula, thula. Shhh, shhh. Go to sleep now.

As she drifts into sleep she hears Mama Thandeka sing, like when she was small and Mama Thandeka tied her to her back inside a towel while she washed the floors. She falls asleep with one ear against Mama Thandeka’s vibrating lungs.

Thula baba, lala baba, ndizobanawe … Hush, my baby, go to sleep, I’ll be with you counting sheep. Dreams will take you far away, sleep until the break of the day.

◊◊◊

The night has arrived here in our house on the mountain ridge. I sit on the chair in front of the inside fire to get warm. It is cold and wet outside in the veld, but cold and dry inside my heart. Abel gone to the Other Side, gone before I could say goodbye, has knocked the breath out of this old black woman. Missus Sarah gone too. And when I think of Gertruidah it seems my thoughts get stuck inside my skull. Nkosi alone knows what will happen now.

It was He who sent the kudu. Now it is He who must keep watch.

When Mabel came home with the half bucket of milk she covered my legs with the red blanket and pushed the chair closer to the fire. ‘Mabel, does Gertruidah look sad, does she look like one who has cried?’

‘No, Mama, Gertruidah doesn’t cry. But she did remember to get the things for Mama’s chest. I’m going to rub the Vicks into Mama’s chest, then Mama will sit by the fire so Mama won’t go to bed feeling cold.’

Then she warmed her hand over the fire and I felt it slide down inside the front of my nightgown. ‘What’s going on in the yard, Mabel? Does Gertruidah have the gun?’

‘She was busy at the chicken coop, her funeral clothes are sopping wet. The gun is on the stoep by the front door. Heaven forbid the police should come here and see the gun was just left lying around, it’ll be prison next. But Mama mustn’t worry, I’ll keep my eye on what’s going on there.’

I feel the cold leave my back as she rubs me and the Vicks fumes rise and clear my head a little. This head has been confused for a long time now, because I’m already seventy-three years old. Sometimes it thinks in the ways of my yellow-brown husband, Samuel, dead long ago. Other times it thinks in the ways of the white people of Umbrella Tree Farm. But there are times, like now when the sadness takes me and I can see the black angel waiting in the doorway, when my head remembers the way my mama talked. The things of your mama, they keep stirring somewhere inside you, they are never far away.

My mama was buried a long time ago, in a place many mountains away. Where the dappled cows graze in the long grass and the women carry bundles of firewood home on their heads in the afternoon. I could be walking with them now, that’s how clearly I see them. I can hear the hadedah calling out from the orange and purple evening clouds saying somewhere a baby has been born. I see my mama adding potatoes to the pot with our evening meal. Or on her knees beside the river. Rubbing the clothes so the foam runs off the washing-stone and floats away on the shallow water. As clear as the present.

I become more and more like a child as I grow older, or like a firm-breasted ntombi, sometimes, and inside my mouth my tongue speaks the language of my mama and tata. At times I am frightened because I cannot remember all the words. Then I tell my heart, it is only because you have been away from your people a long time. You are not that ntombi any more, Thandeka – you are someone else.

This is true.

It is fifty-three years ago that I came to Umbrella Tree Farm, far away from the round house of my childhood. The house with the beautiful patterns my mama painted around the doors and windows, with berry juice, yellow river mud and nightshade extract. She told me a hadedah left me under the sweet thorn at sundown and she wrapped me in her red blanket and ran inside the house before the tokoloshe could get me.

My mama, my mama …

I can smell the cow dung she rubbed on the mud floor, hear her voice fill the yard with a song while she crushes the corn. But it’s all a long way away and some things have grown dim. There are many things you forget in fifty-three years but you never forget how to pray in your mama’s tongue. And when great sorrow overtakes you, then you cry in the language of your childhood.

Many twists on the road of life have brought me to this place, where I sit by the fire with a heart that bleeds because a white man has died.

When I took Samuel Malgas for my husband, my people were unhappy because he was a coloured man. They were unhappy even though they knew he had been to school and was raised in a good home on white people’s land, the farm where my people went to buy food from the trading post on Saturdays. When the shop was busy, Samuel helped out behind the counter, a pencil stuck behind his ear. Quick he was, with adding and subtracting. That was where he and I started looking at each other. Times were different, then; people didn’t just pay court to this one and that. And everyone knew that when Samuel Malgas was a child with the mumps the swelling in his neck went to lie in his groin. My people said I would be a poor woman one day, with no children to look after me when I was old.

Samuel was such a beautiful biblical name. I could tell that the tawny man had a clever head and that his eyes saw the world differently. They seemed to see further than where the mountain ended. And even if he could give me no children he could take me over that mountain and show me new things. When his donkey cart and his donkeys were ready, he said, he would be on his way to see the world.

On the reed mat in my mama’s round house I cried about Samuel who was leaving to see the world. And I stopped going to the store.

But one Sunday afternoon he came all the way to find me.

‘Thandeka, why don’t I see you at the store any more?’ he asked. ‘And why are you crying?’

I stood up and picked up the water bucket. ‘Let’s go fetch water from the river.’

At the river I broke off a reed and told him to make a whistle and think of me whenever he played it.

‘Won’t you come with me, Thandeka? We can get married out of your tata’s house. There’s enough money in my bank book for three lobola cattle … Then together we’ll go see what lies on the other side of the mountain.’

So I took him, because he wanted me. And because I wanted to see the other side of the mountain.

I did have one child, from Abel. And she has taken good care of me all these years.

The red blanket warms my knees and legs. But the cold never seems to leave my backbone, those tiny bones that cradle my marrow, and it stays cold inside my heart. Because Samuel died a long time ago.

And now Abel is dead.

Soon it will be my time. Abel always said if my time came he would lay me to rest on Umbrella Tree Farm, right next to Samuel. He would have a headstone made that would run from my end of the grave to Samuel’s. And he would have my name and my years written on it.

Thandeka Malgas.

Born 30 March 1935, until the day Nkosi our God came for her.

Abel was still a strong man, fifty-eight years old. I am fifteen years older, and almost blind. I should have gone first.

That Gertruidah had them buried in the town cemetery, that I understand. But time passes. Your anger mellows, and your sorrow grows. Then it is too late to open the graves and dig fresh holes. Maybe the wind will carry my breath to the town cemetery so he will hear me when I say: Have a safe journey, Abel …

No one but Thandeka Malgas knows who Abel Strydom really was or how the bones fell for him.

Samuel and I travelled many roads in our donkey cart. How those roads brought us to Umbrella Tree Farm I no longer remember. The donkeys were tired and Samuel said it was time to settle down and make a home.

Abel was only about five years old, a beautiful child. Except for his clothes you had to look closely to see he wasn’t a girl. I cooked the food and rubbed the floors. Did the washing and ironing. There were beds to make, windows to wash, the stoep to sweep. And lots of other jobs Abel’s mama gave me to do.

She was a good person. She always said, take half the eggs or the leguan will eat them. That is what a leguan does; he sneaks around the chicken coop once he has sucked out the cow with his blue and yellow tongue. Don’t tell the old man, she said. Because he was a difficult one. Not an old man in years but with a heart that was old and black. Left deep marks on Abel, I will swear before God to this day.

I helped keep an eye on the children. Three boys and I had a soft spot for Abel because he was the smallest. With soft little feet so I had to give him a piggyback across the devil’s thorn. Then one day a cobra came into the house and bit his mama who was busy in the kitchen with a bowl of green figs and the pricking needle. No matter how hard we sucked to get the poison out of her, by sunset the cobra poison had squeezed out her final breath.

It is hard growing up without your mama.

It is even harder if your papa pushes you away. It can twist a child’s eyes, so the world squints back at him. There were many mornings when I dragged the wet mattress to the back of the pit lavatory where the old man wouldn’t see it. Because if he saw, his tongue would become sharp as a knife blade, ready to draw blood. Time passes and the child becomes a soft-bearded young man who trembles before his papa. By the time that man has grown, everything inside his head has become twisted.

The next time Gertruidah comes here I must tell her what her father and I agreed. That she must tell the headstone people to write Samuel’s name and his years on his end of the stone. And that on my side they must write that my name means ‘good person’.

There are times when I’m good.

Times when I’m bad.

Times when I’m in the middle somewhere between good and bad.

My name is easy to say, but my surname feels uneasy on my tongue. Malgas. It doesn’t click like Noqobo, the clan name of my tata. But it is the name Samuel gave me and I must honour it like I honour his memory.

Samuel and Anthony died on the same day, the day the truck went over the cliff. Anthony was ten years old. If Mabel had not gone to fetch kindling, she would have gone over the cliff with them. Just thinking about it makes my blood run cold. Today she is almost thirty-two years old, and I thank Nkosi for His mercy. It is He who decides which child goes and which one stays.

That is the reason I prayed for Miss Sarah every evening under the stars when I could still see in the dark. Anthony’s dying made her go blind – that was the reason she did nothing to stop Abel when she saw things were becoming ugly with Gertruidah. Anthony’s dying twisted and broke her, of that I am certain.

Another thing of which I am certain: There never was an angel to fly around with Abel. Nkosi gives everyone an angel to help them push Satan away but the only angel Abel got was his black mama, Thandeka. The same mama whose body pushed him into a bad thing. And then there was Mabel, growing up in his house and his yard, with a heart she kept filled with stones to hurt him. More blood of his blood, pushing him away. It must have been hard. He was only looking for love, from someone, somewhere, the way we all do.

There were many nights beside the fire when I told her: ‘You must talk to Abel about these things, so they can grow quiet and lie still inside your head.’

‘Let it alone, Mama. A kitchen maid doesn’t argue with the master.’

‘It is bitterness that makes you talk that way, Mabel. He has always …’

‘If I am bitter it’s because of what he’s doing to Gertruidah. One of these days when I’m in town for Mama’s old-age pension, I’m going to walk into the police station and say they must come see what …’

‘Keep your nose out of white people’s business, Mabel. White people know how to watch each other’s backs. Stay away from the police.’

My marrow is cold as ice and my old woman’s heart broken into a thousand pieces when I think that Abel will never come back to Umbrella Tree Farm.

I will call Mabel to heat a little cup of milk for me and to turn my chair around so the heat can find my back. Then, once the milk has warmed my insides, she must help me to my bed. But until then I will stay by the fire and sing Gertruidah’s song. Abel would have wanted me to sing for her. Her bony body may be as strong as any man’s and no pheasant too far away that she couldn’t put a bullet in its head and leave the meat for the pot. But she has no angel to fly around with her, either, and no matter how bad everything became, with his good side Abel loved her.

Thula baba, vala amehlo … Hush, my baby, close your eyes, time to fly to paradise, till the sunlight brings you home, you must dream your dreams alone …