Читать книгу Mt Kilimanjaro & Me - Annette Freeman - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter 3: Motivations

ОглавлениеSydney is a sunny, well-heeled town, with all mod cons and a laid-back leisurely lifestyle. The downtown office high-rises provide sleek and modern workplaces, handy cafés, year-round air-conditioning. The weather is great for driving a convertible with the top down, and the sea sparkles invitingly at weekends. The arts scene is vibrant, the opera fresh, the seafood delicious and the people frank and friendly.

In Tanzania, only twenty percent of the roads in the country are paved, and many of the rest are close to impassable. When it rains, all is mud; and when it’s dry the dust clogs your pores. Elephants, zebras and wildebeest roam about on the endless Serengeti. Beaches trim the eastern sea-board and the exotic island of Zanzibar. Around the foot-hills of Mt. Kilimanjaro, lush coffee plantations and sugar cane create a green belt. In the courts in Arusha, UN people peruse evidence in the Rwanda genocide investigation.

Travelling from the cosy and familiar world of Sydney to Arusha in Tanzania is a fascinating and challenging shift. Tanzania is bordered by Kenya in the north (travellers from the northern hemisphere often approach Tanzania via Nairobi). Malawi, Zambia and Mozambique touch its borders in the south and Burundi, Rwanda and the Democratic Republic of Congo are to the west. Uganda borders Lake Victoria and touches the northern edge of Tanzania, so in total Tanzania has eight neighbours, as well as a sea coast. Tanzania’s land borders are defined by three large lakes: Victoria, the second-largest freshwater lake in the world; Tanganyika, second only to Lake Baykal as the deepest in the world; and Lake Malawi. Three great African rivers have their origins in Tanzania – the Nile, the Zambezi and the Zaire.

The modern nation was formed in 1964 when Tanganyika united with Zanzibar, giving the elided name of ‘Tanzania’. Julius Nyerere was its charismatic socialist leader, who preached nationhood rather than tribal rivalry, and declared Swahili the national language. The seaside city of Dar Es Salaam (‘Dar’ to the locals) is the largest city and probably the best known in Tanzania, although the official capital is a rarely-visited inland city called Dodoma. The palm-fringed islands of the Zanzibar archipelago, once the hub of the ancient spice route and an Arabian stronghold, retain their own character - and occasionally separatist tendencies. But Tanzania as a whole is a relatively stable and well-integrated African nation, experiencing less tribal conflict than some of its neighbours. This is an achievement in itself, considering that Tanzania has around 120 different tribes, plus a whole polyglot of other races, including European (it was part of German East Africa during the years of colonial occupation), Asian and Arabic.

Around Mt. Kilimanjaro, Arusha and the neighbouring town of Moshi are large and bustling centres, serviced by Kilimanjaro International Airport. In addition to coffee, sugar and the unique blue gem tanzanite – mined only near Arusha – the region boasts another great economic draw card, enough to support the building of an international airport: Mt. Kilimanjaro, the highest mountain in Africa. The constant stream of tourists who visit to climb the mountain provides some economic stimulation to an otherwise poor country.

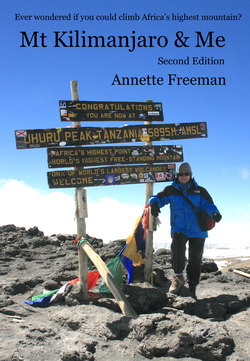

Mt. Kilimanjaro is a trekking peak, meaning that ordinary hikers can manage it. No technical climbing with ropes and pitons and karabiners and so on is required. It is, however, rather high. At 5895 metres, there is a serious risk of high altitude sickness particularly for those who make fast ascents. Some hardy (or foolhardy) souls buzz up Mt. Kilimanjaro in three days. The usual routes take five or six days. The longer routes take seven, eight or nine days, and traverse across the mountain from the west, rather than heading straight up. The valuable advantage of taking a longer route (despite extra expense) is the opportunity to acclimatise, and also to see more of the mountain.

Kilimanjaro is a large free-standing mountain, sixty kilometres long and forty kilometres wide, which rises in more or less solitary splendour out of the East African plain. Despite standing regally apart, it is part of a long chain of mountains sweeping down East Africa along the edges of the Great Rift Valley. Of the active volcanoes in the world, many are found in the mountains of the Great Rift Valley, the cradle of mankind. This is the area of the world where the oldest fossilised remains of humanoid species have been found, including the fossilised human-like footprints of Australopithecus afarensis,found in the Olduvai Valley – along with a fossilised full skeleton, named ‘Lucy’ by her discoverers, all preserved in volcanic ash. When you hear that mankind came ‘out of Africa’, this is the place.

Kilimanjaro, viewed from a distance, is a magnificent looking mountain – oval shaped, hugely tall, with lush greenery at its base, a circlet of cloud around its shoulders, and a cap of iced glaciers. Amazingly, the snows of Kilimanjaro exist only a few degrees south of the equator, and on an active volcano, still warm and sulphurous in its ash cone. No wonder it has drawn adventurers for many years, after being first climbed in the mid-1800s, and first summitted, by Hans Meyer, in 1891.

Kilimanjaro is in fact a three-peaked volcano. The highest cone, in the centre, is called Kibo (5895m) and is the focus of climbers. To the east is Mawenzi (5149m), still a high and challenging peak. The highest point on Mawenzi cannot be reached by mere trekkers and is only rarely visited by mountain climbers. To the west was the third cone, that of Shira, long since collapsed and eroded away, leaving the extensive Shira Plateau, a fine trekking area. Apart from being the highest cone, Kibo has an extra attraction – the glaciers, the famous ‘snows of Kilimanjaro’. Many people have heard that Kilimanjaro’s glaciers are disappearing. Records show that in the mid 1800s, when someone first climbed to the snow line, it was encountered at around 4000 metres. Today the snows begin at around 5000 metres. A great goal of many climbers – including me - is to see the snows of Kilimanjaro before they disappear forever.

But climbing the mountain is no walk in the park. Only a little research reveals many horror stories of jaunty young trekkers knocked off their feet by the effort - the tedious slog up the rocky volcanic scree, the headaches and fatigue common at high altitude, the sheer hard work.

Kilimanjaro has attracted all kinds of nutty adventurers. Since you don’t need climbing expertise to attempt it, many crazy people have used the mountain to set records that would be just plain silly if they didn’t also take incredible endurance. Take the feat of Bruno Brunod, an Italian, who in 2001 ranup Kilimanjaro in five hours 36 minutes and 38 seconds. Not surprisingly, he has been described as ‘barking mad’. And he wasn’t the only one to make unorthodox summit attempts. A pair of English cousins cycled up the mountain with only Mars Bars for sustenance, strapped to their handlebars. A crazy Spaniard drove a motorbike to the summit in the seventies. But the winner of the crazy stakes is possibly Douglas Adams, author of The Hitchhikers’ Guide to the Galaxy, who went all the way to the top in a rubber rhinoceros costume as a stunt for charity in 1994. There is also a story of a man walking all the way up backwards, in an effort to set a record for the Guinness Book, only to find that someone had beaten him by doing the same thing four days previously.

Henry Stedman’s guide book Kilimanjaro – The Trekking Guide To Africa’s Highest Mountainbecame my preferred source of information and stories about climbing Kilimanjaro. Stedman refers to these crazy adventurers, but goes on rather more seriously:

… it’s no wonder, given the sheer number of people who have climbed Kili over the past century, and the ways in which they’ve done so, that so many people believe that climbing Kili is a doddle. And you’d be forgiven for thinking the same.

You’d be forgiven – but you’d also be wrong. Whilst these stories of successful expeditions tend to receive a lot of coverage, they also serve to obscure the tales of suffering and tragedy that often go with them. To give you just one example: for all the coverage of the Millennium celebrations, when over 7000 people stood on the slopes of Kilimanjaro during New Year’s week – with over 1000 on New Year’s Eve alone – little mention was made of the fact that well over a third of all the people who took part in those festivities failed to reach the summit, or indeed get anywhere near it. Or that another 33 had to be rescued. Or that, in the space of those seven days, three people died.

Sobering. So what was mymotivation for leaving safe and sunny Sydney, travelling for two days to Tanzania, and attempting to climb Kilimanjaro myself? It’s a difficult question to answer because the response lies as much in emotional reaction, some deep and mysterious feeling, as it does in logic. To see and touch the famous, transient and almost mythic glaciers – that was a big drawcard. To share another adventure with my trekking buddies, whom I knew from experience would be supportive and enthusiastic, was also a fun prospect. Spending time outdoors, feeling self-reliant and enjoying nature, scenery, mountains, and weather – all attractive. But why Kilimanjaro? Why so high? Certainly there had to be an element of wanting to bag the iconic peak, of being able to say to myself and everyone else that I’d done it. Knocked the bastard off, as Hillary said of Everest. But was I particularly driven by a competitive sporting spirit? Maybe a little.

Australia is a flat country, its tallest mountains being barely more than swellings of the plains. Yet high mountains exert a visceral pull on me. My first glimpse of very tall snow-capped peaks was a seminal moment. I was on a train in Switzerland and the Alps hove into view. I had to bring my head down to knee level and look upwards through the train window to see the tops of the mountains. I was overawed. In the course of the years, travelling, camping, walking and hiking in the (relatively) untouched parts of the world has been the source of my most precious moments of contentment. A contemplative few minutes sitting in nature, preferably in silence, preferably with a sweeping and improbably gorgeous view spread before me, is more than a hiker’s rest. The moment can warm that little spiritual flame inside and the world in that moment is precious, explicable and completely right. Somewhere inside of me I seem to have taken to heart the words of the Psalmist learnt by rote in my childhood Sunday School class: ‘I lift up mine eyes unto the hills, from whence cometh my help …’

And there’s a more practical element, too. Stretching myself, getting out of my comfort zone, proving I can attempt an unlikely adventure, is quietly satisfying. Quite simply, it makes me feel alive. And it also makes me feel and believe that anything is possible. Anything at all. That’s quite a feeling. No wonder then that I eagerly planned to exchange my feather-down bed and quiet back garden for a sleeping bag and tent on the rocky ground of a dry and cold mountainside in Africa. For eight nights and nine days. Without plumbing.