Читать книгу Portrait of a Scandal - Энни Берроуз, Annie Burrows - Страница 9

ОглавлениеChapter One

‘Madame, je vous assure, there is no need to inspect the kitchens.’

‘Mademoiselle,’ retorted Amethyst firmly as she pushed past Monsieur Le Brun—or Monsieur Le Prune, as she’d come to think of him, so wrinkled did his mouth become whenever she did not tamely fall in with his suggestions.

‘Is not the apartment to your satisfaction?’

‘The rooms I have so far seen are most satisfactory,’ she conceded. But at the sound of crashing crockery from behind the scuffed door that led to the kitchens, she cocked her head.

‘That,’ said Monsieur Le Brun, drawing himself to his full height and assuming his most quelling manner, ‘is a problem the most insignificant. And besides which, it is my duty to deal with the matters domestic.’

‘Not in any household I run,’ Amethyst muttered to herself as she pushed open the door.

Crouched by the sink was a scullery maid, weeping over a pile of broken crockery. And by a door which led to a dingy courtyard she saw two red-faced men, engaged in a discussion which involved not only a stream of unintelligible words, but also a great deal of arm waving.

‘The one with the apron is our chef,’ said Monsieur Le Brun’s voice into her ear, making her jump. She’d been so intent on trying to work out what was going on in the kitchen, she hadn’t heard him sneak up behind her.

‘He has the reputation of an artist,’ he continued. ‘You told me to employ only the best and he is that. The other is a troublemaker, who inhabits the fifth floor, but who should be thrown out, as you English say, on his ear. If you will permit...’ he began in a voice heavily laced with sarcasm, ‘I shall resolve the issue. Since,’ he continued suavely, as she turned to raise her eyebrows at him, ‘you have employed me to deal with the problems. And to speak the French language on your behalf.’

Amethyst took another look at the two men, whose rapid flow of angry words and flailing arms she would have wanted to avoid in any language.

‘Very well, monsieur,’ she said through gritted teeth. ‘I shall go to my room and see to the unpacking.’

‘I shall come and report to you there when I have resolved this matter,’ he said. Then bowed the particular bow he’d perfected which managed to incorporate something of a sneer.

‘Though he might as well have poked out his tongue and said “so there”,’ fumed Amethyst when she reached the room allocated to her travelling companion, Fenella Mountsorrel. ‘I think I would prefer him if he did.’

‘I don’t suppose he wishes to lose his job,’ replied Mrs Mountsorrel. ‘Perhaps,’ she added tentatively, as she watched Amethyst yank her bonnet ribbons undone, ‘you ought not to provoke him quite so deliberately.’

‘If I didn’t,’ she retorted, flinging her bonnet on to a handily placed dressing table, ‘he would be even more unbearable. He would order us about, as though we were his servants, not the other way round. He is one of those men who think women incapable of knowing anything and assumes we all want some big strong man to lean on and tell us what to do.’

‘Some of us,’ said her companion wistfully, ‘don’t mind having a big strong man around. Oh, not to tell us what to do. But to lean on, when...when things are difficult.’

Amethyst bit back the retort that sprang to her lips. What good had that attitude done her companion? It had resulted in her being left alone in the world, without a penny to her name, that’s what.

She took a deep breath, tugged off her gloves, and slapped them down next to her bonnet.

‘When things are difficult,’ she said, thrusting her fingers through the thick mass of dark curls she wished, for the umpteenth time, she’d had cut short before setting out on this voyage, ‘you find out just what you are made of. And you and I, Fenella, are made of such stern stuff that we don’t need some overbearing, unreliable, insufferable male dictating to us how to live our lives.’

‘Nevertheless,’ pointed out Fenella doggedly, ‘we could not have come this far, without—’

‘Without employing a man to deal with the more tiresome aspects of travelling so far from home,’ she agreed. ‘Men do have their uses, that I cannot deny.’

Fenella sighed. ‘Not all men are bad.’

‘You are referring to your dear departed Frederick, I suppose,’ she said, tartly, before conceding. ‘But given you were so fond of him, I dare say there must have been something good about him.’

‘He had his faults, I cannot deny it. But I do miss him. And I wish he had lived to see Sophie grow up. And perhaps given her a brother or sister...’

‘And how is Sophie now?’ Amethyst swiftly changed the subject. On the topic of Fenella’s late husband, they would never agree. The plain unvarnished truth was that he had left his widow shamefully unprovided for. His pregnant widow at that. And all Fenella would ever concede was that he was not very wise with money. Not very wise! As far as Amethyst could discover, the man had squandered Fenella’s inheritance on a series of bad investments, whilst living way beyond his means. Leaving Fenella to pick up the pieces...

She took a deep breath. There was no point in getting angry with a man who wasn’t there to defend himself. And whenever she’d voiced her opinion, all it had achieved was to upset Fenella. Which was the last thing she wanted.

‘Sophie still looked dreadfully pale when Francine took her for a lie down,’ said Fenella, with a troubled frown.

‘I am sure she will bounce right back after a nap, and a light meal, the way she usually does.’

They had discovered, after only going ten miles from Stanton Basset, that Sophie was not a good traveller. However well sprung the coach was, whether she sat facing forwards, or backwards, or lay across the seat with her head on her mother’s lap, or a pillow, she suffered dreadfully from motion sickness.

It had meant that the journey had taken twice as long as Monsieur Pruneface had planned, since Sophie needed one day’s respite after each day’s travel.

‘If we miss the meetings you have arranged, then we miss them,’ she’d retorted when he’d pointed out that the delay might cost her several lucrative contracts. ‘If you think I am going to put mercenary considerations before the welfare of this child, then you are very much mistaken.’

‘But then there is also the question of accommodation. With so many people wishing to visit Paris this autumn even I,’ he’d said, striking his chest, ‘may have difficulty arranging an alternative of any sort, let alone something suited to your particular needs.’

‘Couldn’t you write to whoever needs to know that our rooms, and yours, will be paid for no matter how late we arrive? And make some attempt to rearrange the other meetings?’

‘Madame, you must know that France has been flooded with your countrymen, eager to make deals for trade, for several months now. Even had we arrived when stated, and I had seen these men to whom you point me, who knows if they would have done business with you? Competitors may already have done the undercutting...’

‘Then they have undercut me,’ she’d snapped. ‘I will have lost the opportunity to expand on to the continent. But that is my affair, not yours. We will still want your services as a guide, if that is what worries you. And we can just be genuine tourists and enjoy the experience, instead of it being our cover for travelling here.’

He’d muttered something incomprehensible under his breath. But judging from the fact these rooms were ready for them, and that a couple of letters from merchants who might take wares from her factories were already awaiting her attention, he’d done as he’d been told.

At that moment, her train of thought was interrupted by a knock on the door. It was the particularly arrogant knock Monsieur Le Prune always used. How he accomplished it she did not know, but he always managed to convey the sense that he had every right to march straight in, should he wish, and was only pausing, for the merest moment, out of the greatest forbearance for the unaccountably emotional fragility of his female charges.

‘The problem in the kitchen,’ he began the moment he’d opened the door—before Amethyst had given him permission to enter, she noted with resentment—‘it is, I am afraid to say, more serious than we first thought.’

‘Oh, yes?’ It was rather wicked of her, but she relished discovering that something had cropped up that forced him to admit that he was not in complete control of the entire universe. ‘It was not so insignificant after all?’

‘The chef,’ he replied, ignoring her jibe, ‘he tells me that there cannot be the meal he would wish to serve his new guest on her first night in Paris.’

‘No meal?’

‘Not one of the standard that will satisfy him, no. It is a matter of the produce, you understand, which is no longer fit to serve, not even for Englishmen, he informs me. For which I apologise. These are his words, not my own.’

‘Naturally not.’ Though he had thoroughly enjoyed being able to repeat them, she could tell.

‘On account,’ he continued with a twitch to his mouth that looked suspiciously like the beginnings of a smirk, ‘of the fact that we arrived so many days after he was expecting us.’

In other words, if there was a problem, it was her fault. He probably thought that putting the welfare of a child before making money was proof that a woman shouldn’t be running any kind of business, let alone attempting to expand. ‘However, I have a suggestion to make, which will overcome this obstacle.’

‘Oh, yes?’ It had better be good.

‘Indeed,’ he said with a smile which was so self-congratulatory she got an irrational urge to fire him on the spot. That would show him who was in charge.

Only then she’d have to find a replacement for him. And his replacement was bound to be just as irritating. And she’d need to start all over again, teaching him all about her wares, the range of prices at which she would agree to do deals, production schedules and so on.

‘For tonight,’ he said, ‘it would be something totally novel, I think, for you and Madame Montsorrel to eat in a restaurant.’

Before she had time to wonder if he was making some jibe about their provincial origins, he went on, ‘Most of your countrymen are most keen to visit, on their first night in Paris, the Palais Royale, to dine in one of its many establishments.’

The suggestion was so sensible it took the wind out of her sails. It would make them look just like the ordinary tourists they were hoping to be taken for.

‘And before you raise the objection that Sophie cannot be left alone,’ he plunged on swiftly, ‘on her first night in a strange country, I have asked the chef if he can provide the kind of simple fare which I have observed has soothed her stomach before. He assures me he can,’ he said smugly. ‘I have also spoken with Mademoiselle Francine, who has agreed to sit by her bedside, just this once, in the place of her mother, in case she awakes.’

‘You seem to have thought of everything,’ she had to concede.

‘It is what you pay me for,’ he replied, with a supercilious lift of one brow.

That was true. But did he have to point it out quite so often?

‘What do you think, Fenella? Could you bear to go out tonight and leave Sophie? Or perhaps—’ it suddenly occurred to her ‘—you are too tired?’

‘Too tired to actually dine in one of those places we have been reading so much about? Oh, no! Indeed, no.’

The moment Bonaparte had been defeated and exiled to the tiny island of Elba, English tourists had been flocking to visit the country from which they had been effectively barred for the better part of twenty year. And filling newspapers and journals with accounts of their travels.

The more they’d raved about the delights of Paris, the more Amethyst had wanted to go and see it for herself. She’d informed her manager, Jobbings, that she was going to see if she could find new outlets for their wares, now trade embargoes had been lifted. And she would. She really would. She’d already made several appointments to which she would send Monsieur Le Brun, since she assumed French merchants would be as unwilling to do business with a female as English merchants were.

But she intended to take in as many experiences as she could while she was here.

‘Then that is settled.’ Amethyst was so pleased Fenella was completely in tune with her own desire to get out and explore that for once her state of almost permanent irritation with Monsieur Le Brun faded away to nothing.

And she smiled at him.

‘Is there any particular establishment you would recommend?’

‘I?’ He gaped at her.

It was, she acknowledged, probably the first time he had ever seen her smile. At him, at least. But then she had never dared let down her guard around him before. She’d taken pains to question every one of his suggestions and to double-check every arrangement he’d made, just to make sure he never attempted to swindle her. Or thought he might be able to get away with any attempt to swindle her.

And he had got them to Paris. If not quite to his schedule, then at least in reasonable comfort. Nor had he put a foot out of place.

She was beginning to feel reasonably certain he wouldn’t dare. Besides, she had Fenella to double-check any correspondence he wrote on her behalf. Her grasp of French was extremely good, to judge from the way Monsieur Le Brun reacted when he’d first heard her speaking it.

‘The best, the very best,’ he said, making a swift recovery, ‘is most probably Very Frères. It is certainly the most expensive.’

She wrinkled her nose. It sounded like the kind of place people went to show off. It would be crammed full of earls and opera dancers, no doubt.

‘The Mille Colonnes is popular with your countrymen. Although—’ his face fell, ‘—by the time we arrive, there will undoubtedly be a queue to get in.’

She cocked her eyebrow at him. Rising to the unspoken challenge, he continued, ‘There are many other excellent places to which I would not scruple to take you ladies... Le Caveau, for example, where for two to three francs you may have an excellent dinner of soup, fish, meat, dessert and a bottle of wine.’

Since she’d spent some time before setting out getting to grips with the exchange rate, his last statement made her purse her lips. Surely they wouldn’t be able to get anything very appetising for such a paltry sum?

Nevertheless, she did not voice that particular suspicion. Having watched her intently as he’d described what were clearly more expensive establishments, he was probably doing his best to suggest somewhere more economical. He wasn’t a fool. His manner might infuriate her, but she couldn’t deny he was observant and shrewd. Because she’d made him suffer enough for one day and because Fenella had a tendency to get upset if they quarrelled openly in her presence, she admitted that she rather liked the sound of Le Caveau.

* * *

It wasn’t long after that she and Fenella had changed, dressed, kissed a drowsy Sophie goodnight and were stepping out into the dimly lit streets of Paris.

Paris! She was really in Paris. Nothing could tell the world more clearly that she was her own woman. That she was ready to try new things and make her own choices in life. That she’d paid for the follies of her youth. And wasn’t going to carry on living a cloistered existence, as though she was ashamed of herself. For she wasn’t. She’d done nothing to be ashamed of.

Of course, she was not so keen to start becoming her own woman that she was going to abandon all her late Aunt Georgie’s precepts. Not the ones that were practical at any rate. For her foray to the bargain of a restaurant that was Le Caveau, she wore the kind of plain, sensible outfit she would have donned for a visit to her bankers in the City. Monsieur Le Brun had just, but only just, repressed a shudder when he’d seen her emerge from her room. It was the same look she would have expected a member of the ton, in London, to send her way.

Provincial, they would think, writing her off as a nobody because her bonnet was at least three years behind the current fashion.

But it was far better for people to underestimate and overlook you, than to think you were a pigeon for the plucking. If she’d set out for the Continent in a coach and four, trailing wagonloads of servants and luggage, and made an enormous fuss at whatever inn they’d stopped at, she might as well have hung a placard round her neck, announcing ‘Wealthy woman! Come and rob me!’

As it was, they’d had to put up with a certain amount of rudeness and inconvenience on occasion, but nobody had thought them worth the bother of robbing.

And there was another advantage, she soon discovered, to not being dressed in fine silks. ‘I can’t believe how muddy it is everywhere,’ she grumbled, lifting her skirts to try to keep them free from dirt. ‘This is like wading down some country lane that leads to a pig farm.’

‘I suggested to you that it would be the mode to hire a chair for your conveyance to the Palais Royale,’ Monsieur Le Brun snapped back, whiplash smart.

‘Oh, we couldn’t possibly have done that,’ said Fenella, at her most conciliatory. ‘We are not grand ladies. We would both have felt most peculiar being carried through the streets like—’

‘Parcels,’ put in Amethyst. ‘Lugged around by some hulking great porters.’

‘Besides,’ said Fenella hastily,’ we can see so much more of your beautiful city, monsieur, if we walk through it, than we could by peeping through the curtains of some sort of carriage. And feel so much more a part of it.’

‘That is certainly true. The mud certainly looks set to form a lasting part of my skirts,’ observed Amethyst.

But then they stepped through an archway, into an immense, brilliantly lit gravelled square, and whatever derogatory comment she might have made next dried on her lips.

And Monsieur Le Brun smirked in satisfaction as both ladies gaped at the spectacle spread before them.

The Palais Royale was like nowhere she had ever seen before. And it was not just the sight of the tiers of so many brightly lit windows that made her blink, but the crowds of people, all intent on enjoying themselves to the full. To judge from the variety of costumes, they had come from every corner of the globe.

‘This way,’ said Monsieur Le Brun, taking her firmly by the elbow when she slowed down to peer into one of the brightly lit windows of an establishment in a basement. ‘That place is not suitable for ladies such as yourselves.’

Indeed, from the brief glimpse she’d got of all the military uniforms, and the rather free behaviour of the females in their company, she’d already gathered that for herself.

However, for once, she did not shake Monsieur Le Brun’s hand away. It was all rather more...boisterous than she’d imagined. She’d found travelling to London, to consult with her bankers and men of business after her aunt’s death, somewhat daunting, so bustling and noisy was the metropolis in comparison with the sleepy tranquillity of Stanton Basset. But the sheer vivacity of Paris at night was on a different scale altogether.

It was with relief that she passed through the doors of another eatery, which was quickly overtaken by amazement. Even though Monsieur Le Brun had told her this place was economical, it far surpassed her expectations. She had glanced through the grimy windows of chop houses when she’d been in London and had assumed a cheap restaurant in Paris, which admitted members of the public, would resemble one of those. Instead, her eyes were assailed by mirrors and columns, and niches with statues, tables set with glittering cutlery and crystal, diners dressed in fabulous colours and waiters bustling around attentively.

And the food, which she’d half-suspected would be of the same quality she’d endured in the various coaching inns where they’d stayed, was as good as anything she might have tasted when invited to dine with the best families in the county.

But what really made her evening, was to see that the whole enterprise was run by a woman. She sat in state by the door, assigning customers to tables suited to the size of their party, taking their money and tallying it all up in a massive ledger, spread before her on a great granite-topped table.

And nobody seemed to think there was anything untoward about this.

* * *

They had just taken receipt of their dessert when a man, entering alone, inspired a grimace of distaste from Monsieur Le Brun. Her gaze followed the direction of his to see who could have roused his displeasure and she froze, her spoon halfway to her mouth.

Nathan Harcourt.

The disgraced Nathan Harcourt.

Her face went hot while her stomach turned cold, curdling all the fine food inside it to a churning mass of bile.

And the question that had haunted her for years almost forced its way through her clenched teeth in a despairing scream. How could you do that to me, Nathan? How could you?

She wanted to get up, march across the restaurant and soundly slap the cheeks that the proprietress was enthusiastically kissing. Though it was far too late now. She should have done it the night he’d cut her dead, after making a point of dancing with just about every other girl in the ballroom. The night he’d started to break her heart.

He hadn’t changed a bit when it came to spreading his favours about, she noted. The proprietress, who’d merely given them a regal nod when they’d come in, was clasping him to her bosom with such enthusiasm it was a wonder he didn’t disappear into those ample mounds and suffocate.

Which would serve him right.

‘That man,’ said Monsieur Le Brun at his most prune-faced, watching the direction of her affronted gaze, ‘should not be permitted in here at all. But it is as you see. He is in favour with madame, so the customers are subjected to his impertinence. It is regrettable, but not an insurmountable problem. I shall not permit him to disturb you.’

It was too late for that. His arrival had already disturbed her—though Monsieur Le Brun’s words had also roused her curiosity.

‘What do you mean—subjecting the customers to his impertinence?’

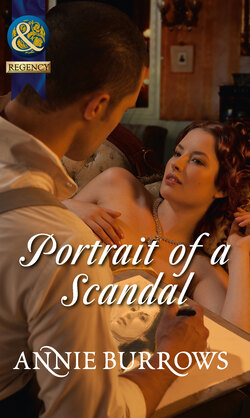

‘He does portraits,’ said Monsieur Le Brun. ‘Quick studies in pencil, for the amusement of the visitors to the city.’

As if to prove his point, Nathan Harcourt produced a little canvas stool from the satchel he had slung over one shoulder, crouched down on it beside one of the tables near the door, took out a stick of charcoal and began to sketch the diners seated there.

‘Portraits? Nathan Harcourt?’

Monsieur Le Brun’s eyebrows shot up into his hairline. ‘You know this man? I would never have thought... I mean,’ he regrouped, adopting his normal slightly supercilious demeanour, ‘though he is a countryman of yours, I would not have thought you moved in the same circles.’

‘Not of late,’ she admitted. ‘Though, at one time, we...did.’

All of ten years ago, to be precise, when she’d been completely ignorant of the nature of men and from too sheltered a background to know how to guard herself against his type. And from too ordinary a background to have anyone sufficiently powerful to protect her from him.

But things were different now.

Different for her and, by the looks of things, very, very different for him too. Her eyes narrowed as she studied his appearance and noted the changes.

Some of them were just due to the passage of years and were pretty much what she would have expected. His face was leaner and flecks of silver glinted here and there amidst curls that had once been coal black. But it was the state of his clothing that most clearly proclaimed the rumours that his father had finally washed his hands of his youngest son were entirely true. His coat only fit where it touched, his hat was a broad-brimmed affair of straw and his trousers were the baggy kind she’d seen the local tradesmen wearing. In short, he looked downright shabby.

Well, well. She leaned back and observed him working with mounting pleasure. When he’d achieved the almost-impossible feat of becoming too notorious for any political party to put him up for even the most rotten of rotten boroughs, he’d vanished, amidst much speculation. She’d assumed that, like the younger sons of so many eminent families, when he’d blotted the escutcheon, he’d been sent to the Continent to live a life of luxurious indolence.

But it looked as though his father, the Earl of Finchingfield, had been every bit as furious as the scandal sheets had hinted at the time and as unforgiving as her own father. For here was Nathan Harcourt, the proud, cold-hearted Nathan Harcourt, forced to work to earn a crust.

‘I shall not be at all displeased if he should come to my table and solicit my custom,’ she said, a strange thrill shivering through her whole being. ‘In fact, I would thoroughly enjoy having my portrait done.’

By him. Having him solicit her for her time, her money, her custom, when ten years ago, he had been too...proud and mighty, and...ambitious to have his name linked with hers.

Oh, what sweet revenge. Here he was, practically begging for a living and not doing too well from the look of his clothing. While here she was, thanks to Aunt Georgie, in possession of so much wealth she would be hard pressed to run through it in ten lifetimes.