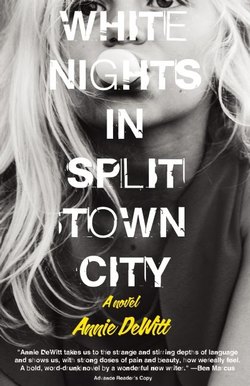

Читать книгу White Nights in Split Town City - Annie DeWitt - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление2.

The hill on our front lawn housed what Father called two trees of knowledge, old apple trees that flowered in the spring and shed small bitter apples in the fall. The yearly continuation of this cycle was inexplicable. Having fallen under the care of a long line of neglectful owners who had failed to prune away the dead wood to make way for the new sprouts, their fruit all but went to seed on the branch. And yet each spring the trees sprouted great plumage, large white blossoms that, if you sat at the base of the trees, smelled like a mixture of honey and vinegar.

I attributed this cycle to what I’d once heard Mother call the wayside of things. “The wayside of what?” I’d said. Mother was sitting in the living room then, in her blue bathrobe, her arm draped over the couch near the back window which she had cracked just wide enough that she could ash out of it.

“The wayside of life,” she said. She tapped her cigarette on the sill and stared vacantly across the deck, her eyes trained on the three men on horseback who were cresting the top of Fay Mountain, about to disappear under the power lines that ran down the back.

Mother extinguished her cigarette, flicking the butt out the window. She got up to turn on the fan so that the smoke blew out over the porch and the air came back into the room. As she sat back down on the couch, she leaned slightly forward and folded her hands. This position was the way she introduced speaking opportunities, times when she would tell me something I wasn’t supposed to hear. Times I would listen. The thing I learned from this opportunity was that the wayside was a place where Father had brought her, this house on a road with aging neighbors where a city girl like herself lost the occasion to put on a pair of decent shoes and escape the house.

Mother had a whole closet of shoes. They were lined up on the floor in the back under her dresses. Birdie and I tried them on evenings when she and Father went out. We were always careful to put them back just in their order. We called these shoes her lady slippers. We had first heard about the extraordinary nature of lady slippers when Father pointed them out to us one afternoon while hiking the land out back of the house. The flowers were rare. They were small and white and delicate, like the inside of a child’s palm planted in the grass.

Being that we grew up on the wayside, Birdie and I often burned off the afternoon hunting about the yard, inventing games under the trees. These games were best played when the grass had just been mowed and the clippings stuck to your body. Afterward, when you got a good hosing, you could really see the grass coming down, you could really watch yourself being stripped of earth.

From his window across the street, Otto Houser watched our games of rolling down the hill and blasting each other with the hose. He said it looked like we were wearing our birthday suits. But, there weren’t any birthdays that summer. Birdie was born in May. I was born in November.

In the evenings, Otto sat on the couch in front of his picture window and watched me finger away at the piano. The learning books came in a box with a set of tapes, which I listened to each day before sitting down and reading the notes. The piano was an old baby grand, an antique Father had bought at the town hall flea market from the cabinetmaker who sold restored furniture out of his flatbed. The only room large enough for Baby was the portico at the front of our house where Mother kept the dining table her parents had sent her, the one with the feet that looked like bird talons. Father called the table Old Eagle Back.

The morning Baby arrived, Father moved Old Eagle Back into the basement. Mother was at church. The man who delivered Baby was there to help.

“All a man needs, Jean,” Father told me as he carried Old Eagle across the living room and down the stairs. “A little bit of music. And an extra set of hands.”

Baby was an instant hotshot. All black around the body, she came with a hood that you propped open when you played to let the music out. Sometimes after practice, I’d imagine crawling under the hood and closing the top over me, just to feel the tension in the strings.

For a short stint after Baby arrived Father’s brother joined us over a series of weekends. Uncle’s real name was Dutch but everyone called him Sterling. Sterling lived a few hours away in a small manufacturing city. He worked at a plastics factory and lived in an old two-story motel where he kept a permanent room. What I knew of Uncle was that he had a strong alto voice and a red sports car. Those nights he joined us, Father drank cans of light beer while Sterling told stories about the men who worked next to him at the plastics factory over bottles of wine and fingers of Old Granddad. Sterling got on too much about old times.

“Leave it alone,” Father’d say.

“Is it wrong for a man to talk about his father?” Sterling would say, and they’d retire to the piano.

Sterling had a penchant for Italian opera. It was one of many tastes no one could account for. Those nights he visited, Sterling sang at Father’s back, performing long stretches of lively arias with precision and grace, defying any suggestion of handicap by the hour or the bottle.

Why he dropped in on us that short stint of nights that summer, Father couldn’t explain. Several weeks after his arrival, Sterling took his red sports car and drove west toward the desert for several days until he reached the part of the country where the grass gets tall and his little red car could disappear among the sheaves of wheat like an ant navigating through thick blades of crab grass. This was how I pictured that part of the country and the distance it put between me and Uncle in my mind. “Big Sky Country,” Sterling had once described it. “Out there you get a piece of sky bigger than the view from New Guinea. All you got to do is step outside and you feel like you could pull a bird down from the clouds with your own two hands. That’s how close you are to your own expectations. You don’t have to go climbing any mountains just to feel so small and alive. Just walking the fields you start to feel your arms lift a little.”

Father abandoned the piano for several weeks after Sterling left. It sat empty for a string of evenings until one night after dinner, I took up again with my method. I was determined to will some part of Sterling’s freedom back into our lives before it abandoned us entirely.

Thus, I first came to notice Otto Houser during a period of great mourning. Our introduction came as I got up to open the window one evening after practice. The heat that night was thick. It was as though the radiator had been bled for the first time that season and a hot steam had descended over our little road. Under the lamp, my face was slick with sweat. My body was dank and my bathing suit clung to my crotch. I stood at the window hoping to catch some movement in the air.

Otto was sitting on his porch, not unusual given the hour. In my experience, the heat often drove people outdoors. Being that I was young, I was still under the guise that I was shielded by darkness. I could barely make out the outline of the old man’s figure in the gathering darkness of the veranda. I stared at him for a moment while picking at my swimsuit and wiping the sweat from my brow.

This particular bathing suit had allure. The allure was the reason I had chosen it, had barely taken it off my body since I had picked it off the rack. It was white with three holes on each side, which were fastened together with pink plastic buttons. When I lifted my arms toward the piano, you could see three patches of flesh running up the side of my body. This, I imagined, was what people meant by “untouchable combinations.” I’d heard a neighbor use those words once when telling Father an anecdote about breeding. He’d recently sired a Doberman with a Golden Retriever. “In the end,” he said, “You’re looking at a good, kind dog with a strong snout. The snout gives the Doberman away, but it’s the combination that’s untouchable.” This was also how I imagined Sterling’s actress friend would have dressed for him.

When I played, Otto Houser said he had the feeling that he was glimpsing some rare, unidentified talent. He observed me from across the road. The details of the piece, he said, he could not discern at his precise distance. From his place on the porch, unable to hear the sounds I made, he watched instead for some forward thrust in my body to suggest the recurrence of a chord or the emergence of melody. He particularly admired those passages where the thin waft of one of my arms eagled-out as it ran up and down an octave. Otto enjoyed those segments of the old television variety hours that featured some new emerging talent, often a corn-fed, blond-haired youth with his or her sights set on the big city lights. These displays of talent produced a rising in Otto’s chest, he said. Their fame nearly embraced him.

On the warmer days, I played in the mornings before the sun was already on us. One noon after practice I went out into the yard to get the mail. Otto Houser was sitting in a rusty beach chair he’d brought onto his porch. Later, once I’d come to know him, he said when the sun was overhead and the shade was right, he liked to sit under the cover of the veranda and eat peanuts while he watched me play. He liked to suck the salt off the shells.

“Hey, Hotshot,” Otto called across the road to me the first afternoon we spoke. I turned to look at him. It was the first time I had known a man to notice me. I could see my reflection in the window at his back. There wasn’t much curve to me. Twelve going on thirteen, I’d grown four inches that year. My chest was still flat. I hadn’t yet embodied the weight of the world, as Mother said. I fumbled with the mail. One of the envelopes slipped off the top of the stack.

“You missed a note,” Otto said.