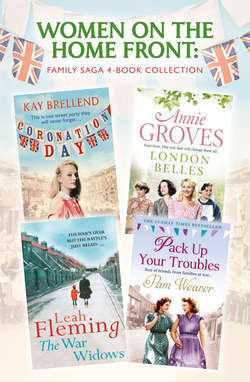

Читать книгу Women on the Home Front: Family Saga 4-Book Collection - Annie Groves, Annie Groves - Страница 21

ОглавлениеChapter Eleven

‘That was a lovely smooth gear change. You’re really getting the hang of it,’ Sergeant Dawson praised Olive as she drove down Article Row, changing through the gears as she did so.

Pink with delight and pride, Olive remembered just in time not to look at her instructor but instead to keep her attention focused on the road in front of her.

It was just over a month now since she had had her first lesson. The ending of British Summer Time and the shortening days meant that there were fewer daylight hours in which Sergeant Dawson could give both her and Mrs Morrison their driving lessons. She had been right to follow her own judgement and not listen to Nancy, Olive congratulated herself, because Sergeant Dawson’s manner towards her had been all that she had known it would be: kind and friendly, but never ever stepping over the line that divided their relationship as neighbours and friends, mixed with a dash of professionalism from him as her driving instructor, from one that involved the kind of looks, comments and hints that would have warned her that he was looking for something else. She felt completely safe in his company, and knew that even her critical late mother-in-law could not have found anything to object to in his manner towards her.

Had things been otherwise she could not have relaxed and focused on learning to drive, Olive knew, as she waited automatically for that second when the clutch bit and depressed slightly when she pressed down the accelerator pedal, heralding the right moment at which to change gear. She could still remember how anxious she had been during that first lesson when Sergeant Dawson had demonstrated this all-important skill to her and she had sat next to him, privately unable to believe that she would ever understand the mechanics of changing gear, never mind actually driving.

Now she was familiar with such terms as double declutching, knew what the ‘bite’ point for changing gear was, could turn corners neatly and even reverse, and during their weekly WVS meetings she and Anne Morrison sat together exchanging tips and horror stories about their lessons, both ruefully admitting to each other how nervous they had been about that first lesson and how thrilled they were now that they were actually driving.

Olive hadn’t forgotten Nancy’s warning to her, but even though her response to it had led to a certain coolness between them on Nancy’s side, Olive didn’t regret her decision or her defiance. Learning to drive made her feel that she really would be able to do something useful, should the need arise. Times were changing and her sex was changing with it: today’s women, with their men going off to war, were having to take charge of their own lives, make their own decisions, and take on the jobs that now needed doing. Today’s women weren’t shrinking violets who never stepped outside their front door without needing to ask a man’s permission, and she certainly wasn’t going to allow Nancy to tell her what she could and could not do.

‘You can put your mind at ease with regard to young Ted, by the way,’ Sergeant Dawson broke the silence between them after they had reached the far end of Article Row and Olive had turned left into its neighbour, Merton Road, which led eventually onto Chancery Lane.

‘I’ve been making a few enquiries about the lad like I said I would and it turns out that he’s generally regarded as a decent sort. Just to be on the safe side I had a word with him myself.’

When Olive forgot his instructions not to turn to look at him, he shook his head.

‘All very discreet, I promise you. I’ve been into that café where he meets Agnes a few times now – thinks a lot of him, the owner of it does – so I arranged to be there one morning when he was coming off his night shift and I knew Agnes wouldn’t be around and I made it my business to fall into conversation with him, like.’

The sergeant gave a small sigh. ‘Lost his father when he was younger so now he’s pretty much the main breadwinner for the family. I reckon he’s a son any chap could be proud of.’

Guessing that he was thinking of his own lost son Olive felt a stab of sympathy for him but she was too tactful to say that she had guessed what had caused his deep sigh.

Instead she said. ‘I’m really grateful to you for going to so much trouble, Sergeant Dawson. You’ve put my mind at ease. Like I said when we first talked about it, it isn’t up to me to tell Agnes what she can and can’t do, but since she doesn’t have a mother or any relatives of her own I can’t help but feel responsible for her.’

‘It’s to your credit that you do. But you needn’t fear for her with young Ted,’ Sergeant Dawson assured her, noting approvingly how his pupil manoeuvred the van into position for the right turn that would take them onto Chancery Lane and from there onto Holborn itself, past Holborn Circus and then down to St Paul’s Cathedral, where they would turn round and make their way back.

A November chill was griping the air now, mist and even fog rolling in from the river early in the morning and then again when the afternoon faded into an early dusk. Winter was round the corner and with it the rationing of butter and bacon from mid-December. Olive shivered a little as she concentrated on her driving. The first bombs of the war with Germany had already been dropped on the Shetland Islands; the Royal Oak had been sunk at her base in Scapa Flow by a German torpedo with the loss of over eight hundred men. The papers were warning about the danger to British shipping from German submarines and their deadly torpedoes. The red double-decker London bus in front of them pulled into the kerb at a bus stop, causing Olive to change down and wait for it to set off again because the road was too narrow and too busy for her to risk overtaking it. She didn’t like overtaking, but Sergeant Dawson said that she was going to have to get used to doing so. The bus set off eventually, the rank smell of the diesel coming from its exhaust making Olive wrinkle her nose and think longingly of the comforting warmth of the vegetable soup she’d made earlier in the day for their tea tonight.

‘I do wish that Mum would let us go dancing at the Hammersmith Palais, and stop treating me like a child, especially now that we’ve got our new frocks,’ Tilly said wistfully, repeating a now familiar complaint as she and Agnes sat listening to the wireless whilst Dulcie read Picture Post. Olive had gone out straight after tea to a WVS meeting, and the three girls were on their own in the house as Sally was working nights.

‘If you don’t want your mother treating you like a kid, Tilly, then you should show her that you aren’t and stop behaving like one,’ Dulcie told her.

‘What do you mean?’ Tilly asked.

Dulcie gave a dismissive shrug. ‘Well, for a start I’d never let my ma tell me that I couldn’t go out dancing if I wanted to. I’d just tell her I was going.’

‘I can’t do that,’ Tilly protested.

‘Then go without telling her,’ Dulcie told her.

Tilly gazed at her. ‘You mean go to the Hammersmith Palais without Mum knowing?’

‘Why not?’

‘Oh, Tilly, you can’t do that,’ Agnes protested, shocked.

‘Course she can, if she wants to,’ Dulcie argued. ‘That’s if she’s got the guts to do it and she isn’t really too scared. All she’s got to do is tell her mother that she’s going somewhere else, like the pictures, and then go to the Palais instead.’ Dulcie gave another shrug. ‘Simple.’

‘You mean lie to my mother?’ Tilly asked uncertainly.

It would serve Olive right if Tilly did go to the Palais behind her back, Dulcie decided. She was well aware of the fact that her landlady disapproved of her and was determined to protect her precious daughter from what she saw as Dulcie’s influence. It would be amusing to persuade Tilly to go behind her back.

‘What do you want to do, Tilly? Only be allowed to go to boring church dances for the rest of your life whilst other girls are having fun at proper dances? If you ask me I’d say that it’s your mother’s fault if you have to lie to her to do what any other girl your age can take for granted. Of course, if you want to stay tied to your mother’s apron strings all your life and never be allowed to make your own mind up about what you want to do, then that’s up to you.’

Dulcie’s challenging words were fanning the flames of Tilly’s resentment of her mother’s refusal to let her go to the Hammersmith Palais. Dulcie was right: her mother was wrong to keep on treating her like a child. She thought yearningly of how much she wanted to be allowed to be properly grown up. As Dulcie had said, other girls her age went to proper dances and their mothers didn’t treat them as though they were still schoolgirls. A reckless determination took hold of her.

‘Dulcie is right, Agnes,’ she announced. ‘We’ll go this Saturday. We can tell Mum that we’re going to the pictures, and then when we get back and she can see that we’re perfectly safe then we can tell her where we’ve been. Everything will be all right then because Mum will understand that I’m old enough to go to proper dances,’ Tilly insisted when Agnes continued to look uneasy.

Agnes was looking at her uncertainly but Tilly knew the other girl wouldn’t go against her. Agnes was too gentle for that.

‘It’s the only way to make her see that we’re properly grown up,’ she insisted, adding, ‘You don’t want our new dresses to be wasted on church socials, do you, Agnes?’

‘But how can we wear them to the pictures?’

Agnes had a point, Tilly recognised. But thankfully Dulcie had a solution for the problem.

‘You’ll just have to take them with you in a carrier bag and then change into them in the ladies’.’

Carried away by the excitement of fulfilling her ambition, Tilly nodded enthusiastically. It was wrong to deceive her mother, she knew, but something had to be done to prove to her that she wasn’t a schoolgirl any more. Dulcie was right about that. The end justified the means, Tilly assured herself, soothing her conscience.

Later that night, when she and Tilly were in bed, Agnes whispered across to her, ‘Do you really think it’s all right for us to go to the Hammersmith Palais without telling your mother, Tilly?’

‘Of course it is,’ Tilly assured her. ‘Like Dulcie said, if we let her, Mum will keep on treating us like schoolgirls for ever.’

Agnes admired Tilly too much to doubt her, but the thought of lying to Tilly’s mother, who had been so kind to her, was an uncomfortable weight on her conscience. At the orphanage lying was considered a very serious sin indeed.

She was still feeling worried and uncomfortable about Tilly’s plans for Saturday night the next day, when she found Ted waiting for her at the entrance to the station, after work.

‘Thought we’d have a cuppa together, if you’ve got time,’ Ted told her gruffly.

‘Of course I’ve got time,’ Agnes told him as he fell into step beside her.

The familiar warmth of the café was a welcome relief from the cold wind outside, and Agnes nodded her head when Ted asked her, ‘Cuppa and a teacake?’ before making her way to ‘their’ table next to the window, from where they could look out and watch the world go by. Not that they could look through it now with the blackout in place. And even if they had been able to, there wouldn’t have been much to see, Agnes acknowledged, as she waited for Ted to rejoin her. Not with it going dark by teatime, and no lighting of any kind allowed on the streets.

It wasn’t long after Ted had given their order over the counter before they were served, and Ted had poured them each a cup of tea.

‘Summat’s up,’ he announced after noting the way Agnes’s head drooped as she stirred her tea. ‘Old Smithy’s not been getting you upset, has he?’

Agnes shook her head. ‘No, he’s really nice to me now. Well, most of the time. Sometimes he shouts when his feet are bothering him.’

‘So if it isn’t old Smithy that’s making you look so glum, what is it?’ Ted pressed.

Reluctantly Agnes unburdened herself to him.

After he had heard her out Ted gave a soft whistle. ‘That Dulcie’s a one, isn’t she?’ he announced. ‘Persuading Tilly to lie to her ma.’

‘Tilly’s been wanting to go to the Hammersmith Palais for ages,’ Agnes told him, not wanting to portray her friend in a bad light. ‘She says that once we’ve been and we get home safely then her mother will stop worrying and let us go without us having to pretend that we aren’t doing.’

‘I don’t know about that,’ Ted told her. ‘Mas don’t take kindly to being lied to.’

‘Tilly says it isn’t exactly lying. It’s just pretending that we’re going to the pictures, ’ Agnes defended her.

Ted could see that Agnes was getting upset so he didn’t pursue the subject any further but inwardly he had already made up his mind that on Saturday night, come hell or high water, he intended to be at the Hammersmith Palais to make sure that Agnes didn’t come to any harm. Poor kid. He could see that she didn’t like the idea of deceiving her landlady but that she was too good a friend to Tilly to betray her.

He did have some sympathy with Tilly, though. There was, after all, nothing like being told you couldn’t do something to make a person want to do it. But lying to her ma in order to do it – that wasn’t a good idea at all – and Ted had a strong suspicion that it would all end in tears. In his home, had his dad still been alive, it would have ended up with his dad’s belt being applied to the back of the offending child’s legs.

All day Friday, Tilly’s excitement grew. She dare not think about Saturday night when she was at work in case she went off into her favourite daydream – the one in which Dulcie’s handsome brother suddenly materialised at her side and asked her to dance – and someone noticed and she got told off.

Of course she felt bad about deceiving her mother, but she tried not to think about that. Instead she thought about how exciting it was all going to be and how wonderful she and Agnes were going to look in their new frocks. A small pang of guilt did strike her when she thought about their new dresses. Mum had been so good about letting them have that velvet instead of the plaid, and the new clothes they’d had made from the fabric they’d bought at Portobello Market made both her and Agnes look ever so grown up. Even her mother had said so when they’d shown them off to her. Instead of feeling guilty she had to think instead about being grown up, like Dulcie had said, and proving to her mother that they were old enough to be treated like adults.

Whilst Olive put Tilly’s growing air of tension and excitement down to the fact that her daughter would be wearing her new dress at the coming church dance, Dulcie, who knew better, observed it with slightly malicious glee.

Oh, it was going to be one in the eye for Tilly’s mother, who treated her, Dulcie, as though she didn’t really want her there, when she found out that Tilly had defied her. Olive’s protective manner towards Tilly still irked Dulcie, reminding her as it did of her own mother’s favouring of Edith. Well, let Olive go around with her nose in the air, thinking that her Tilly told her everything and thought she was wonderful; she’d soon find out that she was wrong. Dulcie knew instinctively that Olive would be hurt by Tilly’s deception but she didn’t care. Olive needed bringing down a peg or two. The fact that Dulcie’s machinations might cause a rift between mother and daughter wasn’t something that weighed on her conscience. Why should it? It was plain daft of Olive to try and keep Tilly a kid for ever. In a way she was doing them both a favour.

On Friday evening, when Tilly announced casually that she and Agnes were going to the pictures on Saturday night, Olive didn’t think anything of it. Her head was full of all the things she needed to do for Christmas, only a month away now. She’d got a goose on order, and luckily she’d been able to get in a bit of a supply of butter from the grocer she always used, ahead of the rationing.

‘I expect you’ll be going home for Christmas, Dulcie?’ she asked, her question causing Dulcie to frown. She hadn’t really given much thought to Christmas, but now that Olive had mentioned it and made it plain that she expected her to go home because no doubt she didn’t want her here, Dulcie felt like digging her heels in and being awkward.

‘Well, I’d like to, of course,’ she agreed, giving an exaggerated sigh as she added, ‘especially with my brother expecting to be coming home from France on leave, but I don’t think there’s going to be room for me. Of course, if you don’t want me here . . .’

‘Of course we do, don’t we, Mum?’ Tilly immediately jumped in. ‘It will be more fun if you’re here, Dulcie. We always have a bit of a party on Boxing Day, don’t we, Mum?’

‘I’d hardly call it a party, Tilly, at least not the sort of party Dulcie would enjoy,’ Olive responded pointedly, giving Dulcie a sharp look as though she guessed what she was up to. ‘It’s just a few of our neighbours, that’s all.’

The news that Dulcie’s brother would be home on leave over Christmas had brought a pink glow to Tilly’s cheeks. She could hardly wait for tomorrow night and being able to ask Dulcie more about her brother without her own mother listening in and giving her that disapproving look.

‘Well, I wouldn’t want to put you out,’ said Dulcie with pretend concern.

‘You won’t be putting me out, Dulcie,’ Olive felt obliged to deny. ‘I just thought you would want to be with your own family.’

‘But, Mum, Sally’s going to be staying, and Agnes, of course, and it wouldn’t be the same if Dulcie wasn’t here,’ Tilly protested.

It certainly wouldn’t, Olive thought grimly, but with Tilly such a staunch supporter of Dulcie there was nothing she could say or do other than allow the subject to be dropped, and rework her shopping plans to make sure that she bought in enough to feed all of them.

As she said to Sally later, if it wasn’t for all the inconvenience of the blackout rules, the ugliness of sandbag buildings, and the sight of so many ARP posts and air-raid shelters everywhere you wouldn’t think there was a war on at all.

‘It’s no wonder people are calling it a phoney war.’

‘It may be phoney for us here in London,’ Sally agreed, ‘but we had a young merchant seaman in today whose arm had to be amputated thanks to the wound he’d suffered when his ship was torpedoed by the Germans. He was telling us that the Germans are inflicting serious losses on our merchant fleet, and that the Government aren’t letting on how bad the situation is. He reckons that it will be much more than butter and bacon that goes on ration soon, with so much having to be brought in to the country by sea.’

‘Poor boy,’ Olive sympathised.

‘Yes,’ Sally agreed. The young seaman had been visibly shocked when he’d been told that he would have to lose his arm or risk losing his life because of the gangrene that had set in to the crushed limb. He’d told her worriedly that merchant seamen, unlike men in the Royal Navy, did not get paid when they weren’t actually working at sea, and she had really felt for him, his situation making her aware of how lucky she was, which reminded her . . .

‘I’ll be going out straight from work tomorrow afternoon,’ she told Olive. ‘One of the other nurses has got tickets for several of us for the matinée of the ENSA Drury Lane show. Apparently the theatres are really good about letting nurses have seats at a cheaper rate and when she asked me if I’d like one of them it seemed silly not to say yes.’

‘I should say so,’ Olive agreed. ‘It will do you good to go out and have a bit of fun.’

‘Yes, I think it will,’ Sally agreed happily.