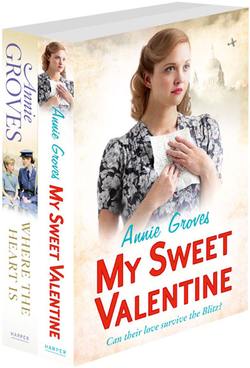

Читать книгу Annie Groves 2-Book Valentine Collection: My Sweet Valentine, Where the Heart Is - Annie Groves, Annie Groves - Страница 16

Eight

Оглавление‘Drew, please let me come with you when you meet up with this man who’s promised to talk to you about this gang of looters he’s involved with,’ Tilly coaxed as she snuggled up next to Drew in the fuggy beer-and-cigarette-scented warmth of their favourite Fleet Street pub, Ye Olde Cheshire Cheese.

‘Tilly, you know I can’t. It might not be safe. Your mother would never forgive me if anything happened to you, and I’d never forgive myself.’

‘What about if something happened to you? I’m tired of having to do what my mother says all the time, Drew. I hate being eighteen. Why can’t I be twenty or, even better, twenty-one, and then I could please myself what I do? You said that I could be involved in finding out more about these looting gangs,’ she reminded him.

‘And you can, but not tomorrow afternoon, Tilly. Look, I’ll make it up to you, I promise. We’re going dancing at the Café de Paris in the West End tomorrow night, remember, with Dulcie and Wilder.’

The newly refurbished nightclub had recently reopened and was very popular with the smart set. Dulcie had insisted on Wilder taking her there to make up for not being able to take her out on Valentine’s Day. The famous ‘Snakehips’ Johnson was to be the band leader for the evening. Once she would have been thrilled at the thought of such a treat, Tilly acknowledged, but not now.

‘Dancing? Who cares about that? I want to be with you when you talk to this looter, Drew. We’re a pair, you said. I want to share what you’re doing. I don’t want to be pushed to one side and kept safe.’

‘You don’t want to go dancing? Is this the Tilly who told me that she wanted to go to the Hammersmith Palais so much that she fibbed to her mother?’ Drew teased.

Tilly wasn’t so easily placated, though. ‘I was just a silly girl then. I’ve grown up now … since I met you. I just want to be with you, Drew,’ she repeated. ‘I want to share in what you’re doing.’

‘Sweetheart, don’t look at me like that,’ Drew protested, reaching for her hand. ‘You know what I’ve promised your mother.’

‘I know that no matter what we promise her, she prefers to believe Nancy than me,’ Tilly objected angrily. ‘She’s proved that. She might say that she accepts that Nancy was wrong and that she’s sorry she doubted me. I think she wants to doubt me so that she’s got an excuse not to let us get married now, like I want to do. She just doesn’t understand. She doesn’t want to understand.’

Drew pulled her closer. He knew how upset Tilly still was about the quarrel she had had with her mother over their Valentine’s Day call at the Simpsons’. He blamed himself for Nancy’s mischief-making and had said so to Tilly’s mother, who had readily accepted his explanation and even apologised to him for doubting them, but that hadn’t been enough for Tilly. Unusually for her she had refused to forgive her mother. Drew had tried gently to persuade her to think again. He knew how much she loved her mother and how much this misunderstanding between them must secretly be hurting her, but Tilly had proved unexpectedly determined not to relent. The reason for that, as Drew knew, was Tilly’s longing for them to be able to marry – and soon. It was a longing he shared, but he didn’t want to make the situation even worse by encouraging Tilly to continue her hostility towards her mother. Drew admired and liked Olive, and in the end he knew that what hurt Olive would hurt Tilly as well, even though right now she would refuse to accept that.

‘Sometimes I think that you’re more on my mother’s side than mine,’ Tilly complained. ‘It makes me wonder if you really do want to marry me, Drew, or—’

‘Of course I want to marry you. Of course I do. You must never think otherwise, Tilly. The only way I could ever stop wanting you to be my wife would be if you told me yourself that you didn’t want that. You must never ever doubt how I feel about you, Tilly. Please promise me that you won’t.’

Tilly’s anger and distress melted away as she heard the genuine emotion in his voice.

‘Very well,’ she agreed, ‘but you’ve got to admit that you do always seem to agree with Mum.’

‘I’m not really taking your mother’s side, Tilly, I just don’t want—’

‘Would you be as willing to understand if it was your mother who was doubting you and refusing to accept that you’re old enough to know your own mind?’ Tilly interrupted him.

The bleak, almost haunted look that suddenly shadowed his eyes suspended her voice, leaving her more concerned about Drew than she was about herself.

‘Drew, what is it?’

‘Nothing.’

‘There must have been something to make you look like that,’ Tilly persisted.

Drew was still holding her hand, and now he began to play with her fingers, stroking them gently, a habit he had when he was thinking deeply about something.

‘Tilly, I don’t—’ he began.

Tightening her fingers comfortingly round his, Tilly interrupted to tell him lovingly, ‘You don’t want there to be upset between me and Mum, I know that, Drew, and so does she.’ Tilly’s voice sharpened, her focus so much on her own grievances that she failed to see the shadow in Drew’s eyes darkening still further before he banished it to listen to her. ‘That’s why she keeps asking you to give her your word about what we can and can’t do. And that’s not fair, it really isn’t. I’ve tried to explain to her how I feel. There are so many women who are alone now because they lost someone during the last war. I see it when I’m typing up records at the hospital of patients’ names and details, I’ve seen it on Article Row with the Misses Barker, and I see it with Mum as well. Now we’re in the middle of another war and if we were to lose one another, Drew, if I were to be the one to have to live on without you, then I know how much I’d need the comfort of my memories of you and our love. Mum’s denying me the opportunity to be happy now and to make those memories because she thinks that us being together properly would make it harder for me. I don’t understand how she can say that. She had her own special time with Dad and she had me because of that.’ Tilly gripped Drew’s hand tightly, her voice blurred with anguish. ‘What she’s saying to me now makes me wonder if she would have preferred not to have had me, Drew.’

‘Tilly, you must never think that,’ Drew protested, anxious to comfort and reassure her. ‘Your mother loves you dearly, anyone can see that.’

‘Yes, she does, but does she secretly wish that she hadn’t had to love me? Does she secretly think that her life would have been easier without me? If she hadn’t married Dad, if she hadn’t had me, then perhaps she might have met and married someone else …’

‘Tilly, your mother would never think anything like that.’

‘How do you know? How do any of us know what someone else really thinks? We can only know what they tell us, can’t we?’

Tilly couldn’t possibly know how guilty those words made Drew feel or how much they cut into his conscience. He should have told her the truth right from the start. If he had … If he had then she wouldn’t be with him like this now. If he had she would have rejected any advances he had made to her, he knew. He mustn’t think about that now, though. He must concentrate on reassuring Tilly that her mother truly loved he.

‘Your mother has always told you that she loves you,’ he reminded her gently. ‘You’ve said that yourself.’

‘She’s said the words, Drew, and I’ve always believed them, but now with her being the way she is over us, I can’t help questioning—’

‘Why don’t you talk to her? Why don’t you tell her what you’ve told me?’

‘What’s the point? She’ll only tell me what she wants me to hear. She wouldn’t want to hurt me, I know that. So she’ll say that I’m wrong, but how can I know that? How can any of us know what another person really feels?’ Tilly moved even closer towards Drew, seeking the comfort of his nearness.

Putting his arm around her as she nestled against him, her head on his shoulder, Drew closed his eyes briefly against the terrible weight of his conscience. He had been so close to telling Tilly everything, so very close. And if he had, would she now be putting him in the same category as her mother, as someone who – she felt she couldn’t trust to be honest with her? If only he’d told her right from the start. But he hadn’t known then that this – they – would happen, and by the time he had known it had been too late to tell her the truth because he had been afraid that the tenderness of their burgeoning new love wouldn’t be able to bear the strain of what he had to say and that she would reject him. Now they must both pay the price of his cowardice – he himself because of the wretched misery he had to live with because he hadn’t told her, and Tilly because his deceit placed in jeopardy her complete trust and belief in him.

‘Come on,’ he told her. ‘We’d better start heading back to Article Row. I’m getting hungry and your mom makes a terrific fish pie.’

Recognising that Drew was trying to lighten her mood, Tilly smiled. It was after all true that her mother was a wonderful homemaker and cook, somehow managing to make their rations stretch to genuinely tasty meals. Drew’s insistence on ‘helping out’ because he was eating so many of his meals at number 13 benefited them all, of course, especially when it came to the boxes of food that came for him from his home in America. Tilly’s mother had tried to refuse this largesse but Drew had simply told her that if she did then it would be wasted because it was far too much for him alone. So her mother had accepted the food but had insisted on donating some of it to the WVS for distribution to those who were homeless.

Friday’s traditional fish pie, though, came from everyone’s rations, even if it was likely to be supplemented by tinned tomatoes from Drew’s mother’s gifts.

The people who eventually assembled at number 13 ready for Sergeant Dawson’s stirrup pump demonstration did not include every member of Olive’s group. Sally was working nights, for one thing, and had left for the hospital, and Ian Simpson and several other neighbours had all been called up for fire-watching duties by their employees. Dulcie, meanwhile, had retired to her bedroom, having flatly refused to get involved, saying that she planned to varnish her nails ready for her evening out at the Ritz. However, there were enough people there to fill Olive’s kitchen and spill out into her hallway.

All of them were, of course, familiar with the sight and the function of a stirrup pump. The devices had been around from the beginning of the war, after all, but since this was the first time they were going to be given the equipment in an official capacity as recognised fire-watchers, rather than individual householders, a mood of determination and responsibility was very much in evidence amongst the older members of the group, especially the Misses Barker, who had been telling Drew how they had wanted to volunteer to drive ambulances during the last war but how their parents had refused to let them.

‘I expect that was because they wanted to protect you,’ Olive offered, overhearing the conversation and giving Tilly a meaningful look.

There wasn’t time for Tilly to retaliate, because a knock on the door had her mother going to admit Sergeant Dawson and one of the young messengers employed by their local ARP unit, who had wheeled round the wheelbarrow from which he and the sergeant removed a Redhill container, a long-handled scoop, a hoe, a galvanised metal bucket and the stirrup pump itself, carrying them into the kitchen, where they carefully put them down in the middle of the circle formed by the would-be fire-watchers.

‘Ideally every household should have its own pump, but we’ve been issued with only enough to provide each street with a couple at the moment,’ Sergeant Dawson informed them before accepting Olive’s offer of a cup of tea.

‘Olive’s given us chocolate as well,’ Miss Mary Barkers told Sergeant Dawson happily.

‘It’s from Drew really. His mother sends it to him from America,’ Olive put in quickly. Nancy wasn’t here but she’d become so aware of her neighbour’s tendency to find fault that automatically she felt defensive.

‘After we gave young Barney his English lesson the other day he asked us if he could have a look in our tool shed to see if there are any spare wheels in there. Of course, we had to tell him that there aren’t.’

The two Misses Barker were retired teachers, and at Sergeant and Mrs Dawson’s request were giving Barney extra lessons to make up for the time he had had off school before they had taken him in.

‘He’s hoping to build himself a bit of a go-cart with some boys he’s got friendly with at school,’ Sergeant Dawson told them. ‘They’ve got some ideas of making their own fire truck. Some of the older boys started making them and following the fire engines, and now the younger ones want to do the same. Barney says that he wants to make an Article Row fire truck.’

‘Oh, how brave of him!’ Jane Barker applauded, asking her sister, ‘Might there be something in the shed amongst Father’s things that he could use, Mary?’

‘Aren’t you worried that Barney could get hurt?’ Olive asked the sergeant.

‘There’s no harm in him making his fire truck, but when it comes to him using it you can be sure that I shall be keeping a very watchful eye on him,’ he assured her.

Olive busied herself pouring the sergeant and the messenger boy cups of tea. After handing the messenger boy his cup she hesitated. If Tilly hadn’t been so deeply engrossed in her conversation with Drew she could have asked her to give the sergeant his tea, but as it was she had no alternative but to take a deep breath and then offer him the cup and saucer.

‘Thanks, Olive.’

When a man had large hands, as Archie Dawson did, it was unavoidable that that hand should touch her own when he took the cup and saucer from her. That might be completely natural, but her own reaction to that brief contact was neither natural nor acceptable in a widow of her age where a married man was concerned, Olive mentally chastised herself.

‘I’ve heard that in some streets they’re setting up a collection so that they can buy their own extra pumps,’ Eric Charlton, one of the tenants who rented number 48, one of Mr King’s properties, announced. A short mousy-looking man with a thin moustache, who worked at the Ministry of Agriculture and who had turned his back garden into a model of a ‘grow your own’ plot, his comment earned him the immediate disapproval of Mr Whittaker from number 50.

‘Ruddy government,’ he said angrily, ‘making us pay for what they should provide us with. It’s bad enough having to form our own fire-watching team without being expected to pay for equipment as well.’ Scowling he glowered at poor Mr Charlton, who huddled closer to his rotund wife, as Len Whittaker gave vent to his feelings.

Anxiously Olive listened to him. His anger did not bode well for the unity of their small group.

As though he had guessed what she was thinking, Archie Dawson leaned towards her and told her in a comforting undertone, ‘Don’t worry about Mr Whittaker leaving, Olive. I reckon he’s just taken the huff because you’ll be having the stirrup pump at this end of the Row. After all, it isn’t as though he couldn’t afford to buy himself one. He’s reckoned to be pretty comfortably off.’

‘You wouldn’t think so from the state of his house,’ Olive whispered back, equally discreetly, as she stepped back slightly from him and tried not to blush when she saw the slightly questioning look he was giving her. She had to stop being so silly. Archie Dawson was a neighbour, after all, and a very good one. He had done nothing wrong. ‘I’ve started taking him down a plated-up Sunday dinner since the Longs left, and number 50 is so thread-bare inside you’d think that he didn’t have two pennies to rub together,’ she told him, determined to behave normally. ‘Poor Mr Charlton was only telling Sally the other day that he’s worried that the seeds from the weeds in Mr Whittaker’s garden are going to blow over and take root in his plot. He has to wage a constant war against them.’

‘A bit like us, then, with these,’ the sergeant told Olive with another smile, gesturing towards the waiting equipment before turning back to the assembled volunteers and telling them, ‘I know that most of you will be aware of how incendiary bombs work, but since we’ve had the Germans dropping this new and more dangerous version of them on us I thought that to start off I’d just run through with you exactly what they are. German planes drop a large bomb casing loaded with small sticks – bomblets – of incendiaries. This casing is designed to open at altitude, scattering the bomblets in order to cover a larger area. Originally the purpose of these was to light up targets for the following planes to drop much heavier bombs on, but since they’ve realised how much damage these incendiaries can inflict on people and their homes, the Germans have taken to dropping even more of them, and they’ve modified them to make them even more dangerous.

‘An explosive charge inside them ignites the incendiary material, which is usually magnesium. This causes a fire, which can extend six to eight feet around the bomb, showering anyone who tries to get close to it with burning pieces of metal. Magnesium can’t be put out by throwing water on it, although of course the fires caused by the sparks can be dowsed in water. It is because of these sparks that we have to have buckets of sand in which to dowse the incendiaries, and why we need to act with speed before they can explode properly.

‘The actual incendiaries, as many of you will have already seen, are bomblets weighing about two pounds, contained in a relatively narrow cylinder. At one end of this cylinder there is a set of sharp fins, which enable the incendiary to penetrate surfaces such as roof tiles and the wooden beams beneath them. It is very, very dangerous for anyone to try to pick up one of these incendiaries without taking the precautions I am going to outline to you in a minute. I must stress how dangerous these newer incendiaries are. They are at their most deadly when they are nearly burned out because that’s when their flames reach the explosive, which is located under the fin. It is therefore the fin and just above it that is the most lethal part of these devices.’

‘Well, I’d heard that the best way to tackle an incendiary, if it hasn’t got fastened into anything, is to grab hold of it, smash it down hard on something to separate it from the fin,’ Eric Charlton said.

‘I have heard of firemen doing that,’ the sergeant agreed, ‘and I’ve also heard of firemen who have lost a hand, or more, through doing it. Here on Article Row we aren’t looking for heroes, especially dead ones.’

Olive noted with gratitude the collective sucked-in breaths of his listeners. How wise he was to give them all a stark warning of the danger of trying to be too gung-ho.

‘Now,’ Sergeant Dawson continued, ‘when it comes to those incendiaries that can be dealt with, this is how to do that.’ Turning towards Olive he asked her, ‘If I could trouble you for a bucketful of water, Ol— Mrs Robbins?’ before turning back to his audience.

‘If you aren’t already doing so just make sure that you fill what you can with cold water at night, just in case, especially baths, because should a local water main be hit then your stirrup pump isn’t going to work.

‘Hitler’s incendiary bombs are designed to penetrate any roofs on which they land, via their sharp fins. Then once they’re safely inside, they’ll explode, showering whatever room they’re in with burning magnesium sparks that will quickly start fires. Our task as fire-watchers is to make sure that that doesn’t happen, and that’s why every time there’s an air-raid warning the first thing you do is make sure that those who are supposed to be watching for falling incendiaries do so. That’s why you need a team of watchers, in pairs say, one every five or six houses. It’s the same principle as that old warning that a stitch in time saves nine. Spotting where the incendiaries fall means that with luck your team can get to them and put them out before they get the opportunity to do any damage. And that’s where your Redhill container and your long-handled shovel and hoe come in.

‘Say, for instance, one of you saw an incendiary fall, the closest watcher would send his or her partner round to the house concerned with their equipment. The long handle of the hoe and the shovel mean that it’s possible for whoever is using them to keep well away from the bomb itself whilst they scoop some sand out of the container to put on the bomb to put the fire out. The sand and the bomb can then be hoed up and placed in the container itself to be doubly sure it is out.

‘As an alternative, or if a fire has already taken hold, what you must do is carefully open the door onto the room with the fire, making sure that you keep the door between you and the fire, and then aim the water from the pump either at the ceiling to fall on the fires, or at the fire itself.

‘Keeping your sand in a wheelbarrow can be a good idea. Then you’ve got it readily transportable.’

‘Well, I certainly won’t be filling my wheelbarrow with sand,’ Mr Charlton protested. ‘I need my barrow for my gardening. And there’s no point in saying we buy more. They can’t be had.’

‘I’m sure we’ll be able to manage between us,’ Olive assured him. It was so kind of Sergeant Dawson to put himself out like this, especially when some people were being so unenthusiastic.

‘If you wish, on Sunday after church I’ll be available to give a practical demonstration of what I mean whilst it’s still light,’ the sergeant offered generously.

‘It all sounds very complicated and dangerous. If you ask me I’d say it would be better for us to let the professionals deal with any fires, instead of trying to do it ourselves,’ said Mrs Charlton apprehensively.

‘Nonsense,’ Miss Jane Barker spoke up firmly, ‘although, Olive my dear, if I can make one suggestion it would be that you pair up those of us who aren’t as agile as we once were for fire-watching duty with a younger person who is steadier and swifter on their feet. I do believe too that we can manage our garden without our wheelbarrow, if that will help.’

Drew smiled as he listened to her. He felt so proud to be accepted by these brave and stalwart people that he had come to admire so much. When he wrote his articles for his newspaper back at home he tried to convey something of the simple unselfconscious, shrugged aside as ‘nothing special’ bravery, of the ordinary people of London, but so often he felt that he was not doing them justice. The truth was, he suspected, that you had to be here to understand and appreciate the true nature of a Londoner’s determination to save their city.

It was gone ten o’clock before everyone had gone, the Misses Barker and, rather surprisingly, Mr Whittaker, lingering until well after the sergeant had excused himself to return to his duties.

‘Of course, the fact that Mr Whittaker is still here has nothing to do with Mum’s offer of supper,’ Tilly said ruefully to Agnes, as she mashed up a tin of American corned beef with some cold boiled potatoes, whilst Agnes diced some onions, ready to make the mix into corned beef hash, for Olive to fry for supper.

‘I feel sorry for him,’ Agnes told her as Tilly wrinkled her nose, grateful that Agnes had volunteered to slice the onions, knowing that Tilly was going out dancing the following night and wouldn’t want any lingering smell on her hands. ‘He must be so lonely living on his own, especially now that the Longs have gone and their house is empty.’

‘You’re a softie, do you know that?’ Tilly teased her. ‘He’s such a crosspatch and so mean.’

‘He used to give money to the orphanage,’ Agnes told her. ‘We all used to be frightened of him because when we walked past his house he would come out into the garden and glare at us. Matron always said that we shouldn’t judge him because only God knows what is truly in a person’s heart.’

‘Is that mash ready, girls?’ Olive demanded, hurrying in from the front room where she’d settled her ‘team’. ‘Put the kettle on again, will you, Tilly? They’ll have to eat their supper in here. I’m not having my front room smelling of fried meat and potato and onions, even if it is a blessing to be able to have onions again after last year’s shortage. Sally’s done us all proud with those she’s grown.’

‘Please change your mind and take me with you tomorrow, Drew,’ Tilly begged a little later when everyone else had left and she was saying a final good night to Drew in the protective darkness outside the front door.

‘You know I can’t,’ said Drew.

‘That means that I’m going to have to do something far more dangerous than sit with you whilst you listen to someone telling you about the looters,’ Tilly sighed.

‘What do you mean?’ Drew demanded, alarmed.

‘I mean that now I’m going to have to go round the markets whilst Dulcie looks for a new dress to wear tomorrow night.’

Drew relaxed. ‘Oh, yes, that sounds very dangerous indeed,’ he agreed, mock solemnly.

‘It will be,’ Tilly assured him. ‘You don’t know what Dulcie can be like when she’s got her mind fixed on something. From the minute she persuaded Wilder to go to the Café de Paris she’s been going on about getting herself what she calls “a really posh frock like ladies and that wear”, and knowing Dulcie, that will mean going round every second-hand stall in London until she finds what she wants.’

‘Mmm, sounds a terrible way to spend a Saturday afternoon,’ Drew agreed, bending his head to kiss her.

‘Afternoon and morning,’ Tilly told him, holding him off for a few seconds before wrapping her arms around his neck and responding to his kiss with an appreciative, ‘Mmm. Drew, that is so nice.’