Читать книгу Some Sunny Day - Annie Groves, Annie Groves - Страница 10

ОглавлениеFIVE

Rosie frowned as she studied her appearance in her dressing-table mirror. Having dipped her forefinger into a pot of Vaseline, she then drew the tip of it along the curve of her dark eyebrows to smooth and shape them, a beauty aid that Bella had shown her.

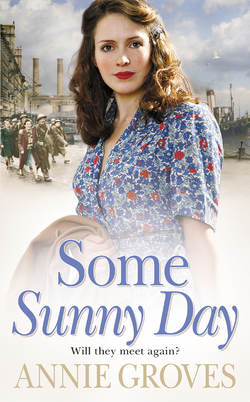

She was wearing a frock she had made herself from a remnant of pretty floral cotton, bright yellow flowers against a white background. She had bought a roll of it at St John’s market in the spring. There had been just enough to make herself a halter-necked frock with a neat nipped-in waist and a panelled skirt.

She had made the halter and trimmed the top of the bodice with some white piqué cotton, and then used the offcuts from the floral material to trim the little matching bolero jacket she had made. The result was an outfit that had brought her more than a few admiring comments. The smile that had been curving her mouth at the memory of those comments dimmed when she remembered how many of them had come from the Grenelli family and how Bella had begged her to make a similar frock and jacket for her. Together they had gone to St John’s every market day until they had found the perfect fabric for Bella’s dark colouring: a deep rich red, patterned with polka dots. They had both worn their new outfits for Bella’s birthday early in May. Less than two months ago but it might as well have been a lifetime ago, so much had changed, Rosie admitted sadly. Her mother hadn’t said anything about the fact that neither of them was visiting the Grenellis any more and, having heard Sofia’s bitter denunciation of Christine, Rosie had felt unable to talk to her about what had happened or why she had stopped visiting their old friends.

‘Where are you off to then?’ her mother demanded now when she saw Rosie dressed up to go out.

‘The Grafton,’ Rosie answered. ‘I’m meeting up with the other girls from work. It was Ruth’s idea. I think she’s feeling a bit low with her Fred in the army, and she wanted a bit of cheering up.’

‘Huh, well, we’d all like a bit of that, I’m sure,’ Christine said sharply. She lit a cigarette and inhaled, then exhaled the smoke, narrowing her eyes. ‘I wouldn’t mind comin’ with yer meself to be honest, Rosie. How do yer fancy havin’ yer old mam along? Mind you, I bet I could show you young ’uns a thing or two,’ she added, her pursed lips relaxing into a small secretive smile.

Rosie’s heart sank. It wasn’t that she didn’t love her mother – she did – but she didn’t feel comfortable about her coming out with them, especially after what Sofia had said.

‘There isn’t time for you to get ready now. I promised the others I’d meet up with them at half-past seven,’ she blurted out.

Her mother’s eyes narrowed again but not against the smoke this time. ‘I see you don’t want me along spoiling your fun.’ She gave a small contemptuous shrug. ‘Please yourself then. I can soon find meself summat to do. As a matter of fact them from the salon are going to the Gaiety tonight and they’ve asked me to go along wi’ them,’ she said, referring to the cinema on Scotland Road.

Rosie felt guilty at how relieved she was to be leaving the house without her mother. It was a pleasant evening, and the city’s streets were still busy with people coming and going, making the most of the light evening and the freedom from the blackout that the dark nights brought.

Like everyone else, Rosie was carrying her gas mask on her arm in its protective box. She had hated having to carry it around all the time at first. It had looked so ugly and felt so cumbersome. But soon, along with other girls, Rosie had been finding imaginative ways to dress up the carrying case with a cover made from scraps of fabric, just like the fancy carrying cases she had seen in the magazines. Automatically she stopped to scan the headlines written up on the newspaper sellers’ sandwich boards, sucking in her breath, her stomach tensing with anxiety that there was more bad news about the Italian men being held.

‘You can allus buy a paper instead of trying to memorise it, love,’ the newspaper seller told her drily, causing passers-by to laugh. Rosie blushed but she too laughed and shook her head. However, the three young lads who had stopped to listen to what was going on, and admire her as they did so, bought a paper apiece.

‘Here, you can stay if you like,’ the seller grinned, winking at her. ‘Pretty lass like you is good for business.’

Rosie laughed again. She was going to be late meeting the others if she wasn’t careful. The lads who had bought papers watched her from the other side of the road, and whistled at her.

Cheek, Rosie thought to herself, tossing her head slightly to let them know what she thought of their impudence, but still secretly pleased by their harmless admiration.

‘There you are. We was just thinking you weren’t going to come,’ Ruth told Rosie, grabbing hold of her arm. ‘Let’s get inside and get a table before it gets too packed.’

The Grafton was one of Liverpool’s most popular dance halls. It had a wide double stairway that led up to the dance hall itself, and on busy nights the stairs could be packed with people eager to dance, as well as some couples standing there smooching, oblivious to the crowd around them. The Grafton was well known for having the very best dance bands on, led by the likes of Victor Silvester, Oscar Rabin and Ivy Benson. As Ruth had predicted, it was already almost full of young people, all keen to enjoy themselves whilst they still could. Of course, the young men in uniform attracted the most interest from the girls in their dance frocks.

‘And remember,’ Ruth cautioned the party from Elegant Modes as they wriggled through the crowd just in time to grab the last vacant table close to the edge of the dance floor, ‘no one’s to go encouraging any RO lads.’

RO lads were the men who were doing very necessary reserved occupation work, but who lacked the glamour of a uniform.

‘That dress looks ever so pretty on you, Rosie,’ Evie Watts, a window dresser at the shop, commented admiringly. ‘I thought so the last time I saw you wearin’ it. Mind you, you ’ave got the figure for it.’

Rosie had just started to thank her for her compliment when Nancy butted in nastily, ‘For meself, I allus think that shop-bought looks smarter than home-made, especially when you’ve had the fabric off of the market and half of Liverpool’s wearing it.’

‘Don’t mind Nancy, Rosie,’ Ruth whispered. ‘She’s just jealous of you on account of her thinking she were the bee’s knees and the prettiest girl in the shop until you come along.’

The band had already started to play and Ruth nudged Evie as a group of young men several yards away edged a bit closer to their table.

‘I’m dancing wi’ the one with the blond hair and blue eyes, in the corporal’s uniform,’ Ruth announced with a predatory gleam in her eyes. ‘He’s got his stripes and I like a lad wi’ a bit of experience about him.’

‘Wot about your Fred?’ Evie demanded

‘Wot about ’im?’ Ruth came back smartly.

When Evie pulled a face behind Ruth’s back and whispered to the others, ‘I fancied that blond lad meself,’ Rosie couldn’t help giggling, her spirits starting to lift.

Ruth might be more outspoken than she was herself but she was such good fun that you couldn’t help but enjoy being in her company. Ruth was always the one for a bit of quick backchat and never behind the door when it came to putting a cheeky lad in his place if she felt like it. Rosie remembered how much it had made her laugh when Ruth had riposted to one particular lad who had swaggered over to them like he was really something, to ask her to dance, ‘Come back in five years when you’re old enough – and tall enough.’

Two girls who Rosie didn’t recognise made their way over and were introduced by Evie as her cousins Susan and Jane. Drinks were ordered, cigarettes lit, and the girls settled down to the ritual of pretending they were oblivious to the way the boys were eyeing them as they smoothed already straight seams and patted immaculately rolled curls, thus showing off slim ankles and shining hair.

‘’Ere, that blond lad’s on his way over. Remember what I said. Hands off, everyone else,’ Ruth warned with a wicked grin.

After a few muttered comments about some girls having the cheek to grab all the best lads before anyone else had a chance to get a good look at them, the girls dutifully clustered together in such a way that the young man was automatically channelled towards Ruth.

‘I reckon it were you he really wanted to dance with, Rosie,’ said Evie as they watched Ruth dancing past them in the arms of the young soldier, who had introduced himself as Bob. ‘There’s no Italian lads here tonight by the looks of it. Shame, ’cos they’re good dancers, and good-lookin’ too.’

Rosie’s smile faded. Evie’s comment had reminded her of the dreadful things that had been happening to the Grenellis. Because of her family’s plans for Bella to marry one of the Podestra boys, Sofia did not allow Bella to go dancing with Rosie, but Bella had always been eager to hear about the fun Rosie had. Dances at the Grafton would be the last thing on Bella’s mind now, Rosie thought, her happiness suddenly shadowed by guilt because she was here and enjoying herself. One of the other young men in army uniform who had been watching them came over and asked her to dance. He was blushing slightly, his brown hair slicked back, and his gaze fixed on a point somewhere past her shoulder. Rosie didn’t have the heart to turn him down. His hand, when he clasped hers, felt hot and slightly sticky, and she could see how self-conscious he felt. His accent wasn’t Liverpudlian, and under her kind questioning he admitted that he had only recently joined up and that he was feeling a bit out of his depth.

‘I didn’t realise that Liverpool was going to be so big,’ he confessed, his honesty and humility making Rosie warm to him.

‘So where are you from, then?’ Rosie asked him.

‘Shropshire,’ he told her. ‘My dad works on a farm down near Ironbridge. I’ve never seen so many houses all together before I came to Liverpool. Nor the sea neither.’

He sounded rather forlorn and Rosie felt quite sorry for him.

‘You must have made friends with some of the other men who joined up at the same time,’ she suggested.

‘Oh, aye, I done that all right,’ he agreed, looking happier. ‘A nicer bunch of blokes you couldn’t hope to meet.’ He gave Rosie a shy grin. ‘After all, it were them as persuaded me to come here tonight. Aye, and it were them an’ all that said I should ask you to dance.’

By the time their dance was over and he had returned Rosie to her table it was surrounded by a jolly crowd of mostly uniformed young men.

Ruth was a flirt, there was no doubt about that, but she was also a big-hearted girl, and Rosie saw how she made sure that even the shyest girl on their table was invited to get up and dance.

‘Here’s Nancy coming over wi’ that cousin of hers wot thinks he’s God’s gift with bells on,’ Evie muttered. ‘Watch out, girls.’

Rosie turned to look at the man coming towards their table. Nancy was at his side and two other young men who were also obviously part of the small group were walking slightly behind him. He was tall, with broad shoulders, his dark hair brilliantined back, and almost film star good looks, apart from the fact that his eyes were too close set, but Rosie knew immediately why Evie had disparaged him. It was all there in those eyes, everything a person needed to know about him, and it made her recoil from him physically. There was not just a coldness but a brutality in his eyes as his darting gaze moved arrogantly over the girls seated at the table. There had been a boy very similar to him at school, Rosie remembered, a bully and a liar who had terrorised the younger children, stealing from them and physically hurting them, until one day the big brother of the small first year he had pushed to the playground, stamping deliberately on his glasses and leaving him crying, had come down to the school and taught him a much-needed lesson.

‘Come on, Lance, you promised you’d dance with me,’ Nancy was wheedling, when they reached the table. She was hanging on to his arm, and looking up at him in a way that was more lover-like than cousinly. It was plain, though, that he did not return her interest because he disentangled himself from her quickly and almost brutally. Rosie could feel him watching her, staring at her, she realised indignantly, as he struck a pose and lit up two cigarettes, withdrawing one from his mouth and then trying to hand it over to her. His action was so deliberately intimate that it made her face burn, not with self-conscious female delight but with anger.

‘No, thank you,’ she told him coolly. ‘I don’t smoke.’

‘But you do dance, right?’

He had put out the cigarettes now, but he hadn’t stopped looking at her and he had moved closer to her as well – so close that she instinctively wanted to put some space between them. But that wasn’t possible with her still seated.

‘What’s happened to them Italian Fascist friends of yours?’ Nancy cut in, taunting Rosie, unhappy the limelight wasn’t shining on her. ‘Or need we ask? All bin imprisoned, I expect, and so they ruddy well should be – aye, and all them wot support them as well. You should be reportin’ her to the authorities, Lance, not asking her to dance.’

‘Supportin’ Fascism – that’s treason, that is,’ Nancy’s cousin announced. The way he was looking at her made the fine hairs on Rosie’s neck rise in angry dislike.

‘Having Italian friends doesn’t make anyone a traitor and it doesn’t mean that they’re Fascists either,’ she defended.

‘I know a group of handy lads, who have their own way of deciding how ruddy Fascists need to be treated. Aye, and they’ve proved it already,’ Lance taunted.

The other girls were beginning to look uncertain and uncomfortable now. Was Nancy’s cousin saying what Rosie thought he was saying? Was he implying that he was one of those who had been involved in the violent riots?

‘Mebbe there are some Italians fighting for Blighty but there’s a hell of a lot more fighting our lads, aye, and killin’ ’em as well. Why take any chances, that’s wot I say. A concentration camp is the best place for the ruddy lot of them,’ Lance told her. His voice had risen as he became more animated, so that the rest of the revellers could hear what he was saying and Rosie could see the approving nods that some of the people standing around them were giving. The earlier light-hearted mood had been replaced by a dark undercurrent of anger and hostility that made her feel vulnerable and afraid.

‘Well, I reckon it’s daft to start thinking that all Italians living here are Fascists because they’re not.’

Everyone turned to look at the young man Rosie had been dancing with earlier. He was facing Lance with an expression of dogged determination on his face that said he wasn’t going to be bullied into backing down. Rosie felt her heart lift as she smiled at her unlikely champion.

‘Alan’s right,’ another young soldier chipped in. ‘We’ve got several Italian lads in our unit and they’re as British as you and me.’

‘Come on, Lance, let’s go and dance,’ Nancy demanded, bored now, grabbing hold of her cousin’s hand and tugging him in the direction of the dance floor.

‘He gives me the willies, that Lance does – those eyes …’ Evie shuddered after they had gone. ‘You did well standing up to him like that, Rosie.’

‘It wasn’t me, it was Alan,’ Rosie replied, giving him a grateful smile.

Perhaps everything would work out after all, especially if there were more people like Alan around.

It had been an enjoyable evening, all the more so when Nancy and Lance had gone over to another table to join some of Lance’s friends, Rosie admitted as she put her key in the back door of number 12. Alan had offered to walk her home but she had walked back as far as Springfield Street with Evie’s cousins instead. She had liked Alan but it didn’t do to go encouraging lads, not even the shy ones, though she was looking forward to telling Bella all about him …

Her smile abruptly disappeared. Ever since Maria had told her that it would be best if she stopped calling round, Rosie had been trying to push her unhappiness about the situation into a corner of her mind where it wouldn’t keep bothering her. But of course she couldn’t. She and Bella had been friends all their lives. They had been best friends practically in their cradles, playing hopscotch together, learning to skip, riding the tricycle that Maria had bought second-hand for them to share, taking it in turns to pedal whilst the one who wasn’t pedalling stood on the back. Then had come their first day at school, when they had stood hand in hand together. If she closed her eyes, even now she could recall the stickiness of their joined hands in their shared nervousness, just as she could recall the loving warmth of Maria’s cuddly body next to her own on her other side. Her own mother had been working and so it had been Maria and Sofia who had taken the girls to school.

Then later she and Bella had walked there together, holding hands, and giggling over their shared secrets and jokes. Then had come ‘big’ school where their friendship had remained as strong as ever. There had hardly ever been a cross word between them. They were as close as sisters – closer. Or rather they had been. Rosie had never imagined that could ever change, but now it had and her heart felt sore and hurt.

She pushed open the door and stepped into the kitchen, quickly closing the door to block out any light that might attract the interest of a watchful ARP patrol.

The first thing she saw was her father’s jacket hanging on its peg and the second was her father himself, propped up asleep in one of the kitchen chairs.

‘Dad!’

He woke immediately at the sound of her excited voice, a smile splitting his face as he looked at her.

Rosie almost flew across the kitchen, flinging herself into his arms, half laughing and half crying. ‘When did you get back?’ she demanded breathlessly.

‘We docked just turned midnight, and they let us off more or less straight away. The Port Authority don’t like us docking until it gets dark just in case the ruddy Luftwaffe teks it into its head to have a go at bombing the docks, so that meant we’d bin waiting out on the other side of Liverpool bar since early this morning. It made me feel right bad being so near but not being able to come and see you straight away. Let’s have a look at yer, lass.’

Obediently Rosie let him hold her at arm’s length whilst he scrutinised her. They had always been close, and Rosie often felt guilty that her love for her father was stronger and went deeper than the love she had for her mother.

‘Summat’s botherin’ you,’ he pronounced shrewdly, his inspection over.

Rosie shook her head in rueful acknowledgement rather than in denial of his judgement.

‘What is it?’

‘Has Mum told you what’s happened to the Grenellis?’ she asked.

She could see him start to frown. Her father was not part of the close friendship she and her mother shared with their Italian neighbours. This was, Rosie had always believed, because he was away so much and had therefore not had the chance to get to know them in the same way. But he was also a quiet man who valued his own fireside when he was not at sea. The busyness of the Grenellis’ kitchen, with people constantly coming and going and voices raised in lively conversation and sometimes equally lively argument, was not something he would enjoy.

‘I haven’t seen your mam yet. She’s out somewhere,’ he muttered.

‘I think she’s gone to the Gaiety, with the others from the salon,’ Rosie told him, ‘and then I expect she went back with one of them for a bit of supper. You know what she’s like about not wanting to be in on her own.’

‘Aye, your mam’s never bin one as has enjoyed her own company,’ Rosie’s father agreed. ‘So you’ve bin worrying that soft heart of yours about the Grenellis, have you? I heard summat down at the docks about the Italian men being taken off.’

‘Dad, it was so awful. There were riots, and then the police came and took the men away. La Nonna was dreadfully upset, and Sofia as well.’

‘They haven’t got anything to worry about if they haven’t done anything wrong,’ her father said reassuringly.

‘Of course they haven’t done anything wrong,’ Rosie immediately replied.

Her father’s expression softened. ‘I know it must be hard for the families that have got caught up in this, Rosie, but it won’t do them or you any good you worrying yourself about it, lass.’

‘I can’t help it …’ She paused and shook her head. ‘Giovanni is nearly seventy-six, Dad, and he doesn’t always understand English properly even though he’s lived here for so long. I can’t understand why the government hasn’t released men like him already.’

‘Governments have their own way of doing things, Rosie, and they don’t allus make a lot o’ sense to ordinary folk like us. How’s your mam taking it?’

‘She hasn’t said much. She went up to Huyton when they first took the men there, but …’

‘But what?’ her father pressed her gently.

Rosie shook her head. ‘I don’t know really, Dad, only that Sofia’s taken everything really badly and there’s been a bit of a falling-out. Mum hasn’t been round to see them since the men were taken and Maria’s asked me not to go until things are sorted out.’ Rosie’s voice thickened, her eyes suddenly filling with tears at being separated from close friends. ‘It made me feel so bad when she said that. I know we aren’t Italian, but we’ve always been friends, and now it’s as though …’

‘It won’t be easy for them, Rosie. Maria’s a good woman and she won’t have intended to hurt you. But sometimes it’s best to stay close to your own when things like this happen. Like to like, kin to kin.’ He gave her a warm hug. ‘You have a good cry if it will make you feel better.’

Rosie gave him a wobbly smile. ‘What a way to welcome you home, Dad – Mum not here and me crying all over you about other people’s problems. I’m so glad you’re home, though. I think about you all the time and I say a special prayer every night that you’ll be kept safe.’

‘You’ve always had a soft heart, you have, our Rosie. Don’t ever lose it. I’m going up to Edge Hill tomorrow to see your Auntie Maude,’ he told her, changing the subject. ‘Why don’t you come with me? She’d like to see you.’

Rosie seriously doubted that but tried not to look unenthusiastic. She knew how strongly he believed he owed his sister for looking after him when their parents died in an outbreak of cholera when he was only twelve years old, and she knew too how much discord it caused between her parents when her mother refused to go and see Maude.

‘Of course I’ll come with you,’ she assured him, and was rewarded with a smile and another hug.

‘I’m for me bed,’ he told her as he released her. ‘I only waited up on account of you not being in.’

‘Don’t you want to stay up for Mum?’ Rosie asked him.

‘No. If I do that I could end up staying down here all night. I didn’t send word to her that we’d docked, and you know your mother … if she’s had a few drinks like as not she’ll stay over with her pals and not come home until morning.’

He said it quite dispassionately but Rosie’s tender heart couldn’t help but feel sad for him. By rights her mother ought to be here waiting to welcome him home but, as they both knew, Christine just wasn’t that sort of woman.