Читать книгу Papillon - Анри Шарьер - Страница 7

Conciergerie

ОглавлениеWhen we reached this last of Marie-Antoinette’s palaces, the gendarmes handed me over to the head warder, who signed a paper, their receipt. They went off without saying anything, but before they left the sergeant shook my two handcuffed hands. Surprise!

The head warder said to me, ‘What did they give you?’

‘Life.’

‘It’s not true?’ He looked at the gendarmes and saw that it was true. This fifty-year-old warder had seen plenty and he knew all about my business: he had the decency to say this to me – ‘The bastards! They must be out of their minds!’

Gently he took off my handcuffs, and he was good-hearted enough to take me to the padded cell himself, one of those kept specially for men condemned to death, for lunatics, very dangerous prisoners and those who have been given penal servitude.

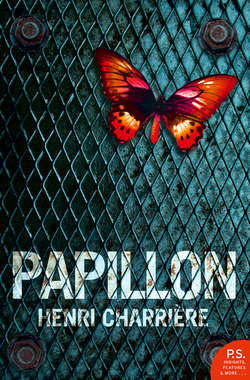

‘Keep your heart up, Papillon,’ he said, closing the door on me. ‘We’ll send you some of your things and the food from your other cell. Cheer up!’

‘Thanks, chief. My heart’s all right, believe me; I hope their penal bleeding servitude will choke them.’

A few minutes later there was a scratching outside the door. ‘What’s up?’ I said.

‘Nothing,’ said a voice. ‘It’s only me putting a card on the door.’

‘Why? What’s it say?’

‘Penal servitude for life. To be watched closely.’

They’re crazy, I thought: do they really suppose that this ton of bricks falling on my head is going to worry me to the point of committing suicide? I am brave and I always shall be brave. I’ll fight everyone and everything. I’ll start right away, tomorrow.

As I drank my coffee the next day I wondered whether I should appeal. What was the point? Should I have any better luck coming up before another court? And how much time would it waste? A year: maybe eighteen months. And all for what – getting twenty years instead of life?

As I had thoroughly made up my mind to escape, the number of years did not count: I remembered what a sentenced prisoner had said to an assize judge. ‘Monsieur, how many years does penal servitude for life last in France?’

I paced up and down my cell. I had sent one wire to comfort my wife and another to a sister who, alone against the world, had done her best to defend her brother. It was over: the curtain had fallen. My people must suffer more than me, and far away in the country my poor father would find it very hard to bear so heavy a cross.

Suddenly my breath stopped: but I was innocent! I was indeed; but for whom? Yes, who was I innocent for? I said to myself, above all don’t you ever arse about telling people you’re innocent: you’ll only get laughed at. Getting life on account of a ponce and then saying it was somebody else that took him apart would be too bleeding comic. Just you keep your trap shut.

All the time I had been inside waiting for trial, both at the Santé and the Conciergerie, it had never occurred to me that I could possibly get a sentence like this, so I had never really thought about what ‘going down the drain’ might be like.

All right. The first thing to do was to get in touch with men who had already been sentenced, men who might later be companions in a break. I picked upon Dega, a guy from Marseilles. I’d certainly see him at the barber’s. He went there every day to get a shave. I asked to go too. Sure enough, when I came in I found him standing there with his nose to the wall. I saw him just as he was making another man move round him so as to have longer to wait for his turn. I got in right next to him, shoving someone else aside. Quickly I whispered, ‘You OK, Dega?’

‘OK, Papi. I got fifteen years. What about you? They say you really copped it.’

‘Yes: I got life.’

‘You’ll appeal?’

‘No. The thing to do is to eat well and to keep fit. Keep your strength up. Dega: we’ll certainly need good muscles. Are you loaded?’

‘Yes. I’ve got ten bags1 in pounds sterling. And you?’

‘No.’

‘Here’s a tip: get loaded quick. Your counsel was Hubert, wasn’t he? He’s a square and he’d never bring you in your charger. Send your wife with it, well filled, to Dante’s. Tell her to give it to Dominique le Riche and I guarantee it’ll reach you.’

‘Ssh. The screw’s watching us.’

‘So we’re having a break for gossip, are we?’ asked the screw.

‘Oh, nothing serious,’ said Dega. ‘He’s telling me he’s sick.’

‘What’s the matter with him? Assizes colic?’ And the fat-arsed screw choked with laughter.

That was life all right. I was on the way down the drain already. A place where you howl with laughter, making cracks about a boy of twenty-five who has been sentenced for the whole of the rest of his life.

I got the charger. It was a beautifully polished aluminium tube that unscrewed exactly in the middle. It had a male half and a female half. There was 5,600 francs in new notes inside. When it was passed to me I kissed it: yes, I kissed this three-and-a-half-inch thumb-thick tube before shoving it into my anus. I drew a deep breath so that it should get right up to my colon. It was my safe-deposit. They could strip me, make me open my legs, make me cough and bend double, but they could never find out whether I had anything. It went up very high into my big intestine. It was part of me. This was life and freedom that I was carrying inside me – the path to revenge. For I was thoroughly determined to have my revenge. Indeed, revenge was all I thought of.

It was dark outside. I was alone in the cell. A strong ceiling light let the screw see me through the little hole in the door. It dazzled me, this light. I laid my folded handkerchief over my eyes, for it really hurt. I was lying on a mattress on an iron bed – no pillow – and all the details of that horrible trial passed through my mind.

Now at this point perhaps I have to be a little tedious, but in order to make the rest of this long tale understandable and in order to thoroughly explain what kept me going in my struggle I must tell everything that came into my mind at that point, everything I really saw with my mind’s eye during those first days when I was a man who had been buried alive.

How was I going to set about things once I had escaped? Because now that I possessed my charger I hadn’t a second’s doubt that I was going to escape. In the first place I should get back to Paris as fast as possible. The first one to kill would be Polein, the false witness. Then the two cops in charge of the case. But just two cops was not enough: I ought to kill the lot. All the cops. Or at least as many as possible. Ah, I had the right idea. Once out, I would get back to Paris, I’d stuff a trunk with explosive. As much as it would hold. Ten, twenty, maybe forty pounds: I wasn’t sure quite how much. And I began working out what it would take to kill a great many people.

Dynamite? No, cheddite was better. And why not nitroglycerine? Right, I’d get advice from the people inside who knew more about it than me. But the cops could really rely upon me to provide what was coming to them, and no short measure, either.

I still had my eyes closed, with the handkerchief keeping them tight shut. Very clearly I could see the trunk, apparently innocent but really crammed with explosives, and the exactly set alarm-clock that would fire the detonator. Take care: it had to go off at ten in the morning in the assembly room of the Police Judiciaire2 on the first floor of 36, quai des Orfèvres. At that moment there would be at least a hundred and fifty cops gathered to hear the report and to get their orders. How many steps to go up? I mustn’t get it wrong.

I should have to work out the exact time it would take for the trunk to get up from the street to the place where it was to explode – work it out to the second. And who was going to carry it? OK: I’d get it in by bluff. I’d take a cab to the door of the Police Judiciaire and in a commanding voice I’d say to the two slops on guard, ‘Take this trunk up to the assembly room for me: I’ll follow. Tell Commissaire Dupont that it’s from Inspecteur chef Dubois, and that I’ll be there right away.’

But would they obey? What if I chanced upon the only two intelligent types among all those idiots? In that case it was no go. I’d have to find something else. Again and again I racked my brains. Deep inside I had no doubt that I should succeed in finding some hundred per cent certain way of doing it.

I got up for a drink of water. All that thinking had given me a headache. I lay down again without the cloth over my eyes: slowly the minutes dropped by. That light, dear God above, that light! I wetted the handkerchief and put it on again. The cold water felt good, and being heavier now the handkerchief fitted better over my eyelids. I would always do it that way from now on.

Those long hours during which I worked out my future revenge were so vivid that I could see myself carrying it out exactly as though the thing was actually being done. All through those nights and even during part of every day, there I was, moving about Paris, as though my escape was something that had already happened. I was dead certain that I should escape and that I should get back to Paris. And of course the first thing to do was to square the account with Polein: and after him, the cops. And what about the members of the jury? Were those bastards to go on living in peace? The poor silly bastards must have gone home very pleased with themselves for having carried out their duty with a capital D. Stuffed with their own importance, they would lord it over their neighbours and their drabble-tailed wives, who would have kept supper back for them.

OK. What was I to do about the jurymen? Nothing. They were poor dreary half-wits. They were in no way fitted to be judges. If one of them was a retired gendarme or a customs-man, he would react like a gendarme or a customs-man. And if he was a milkman, then he’d act like any other dim-wit pedlar. They had gone right along with the public prosecutor and he had had no sort of difficulty in bowling them over. They weren’t really answerable. So that was settled: I’d do them no harm whatsoever.

As I write these thoughts that came to me so vividly all those years ago and that now come crowding back with such terrible clarity, I remember how intensely total silence and complete solitariness can stimulate an imaginary life, when it is inflicted upon a young man shut up in a cell – how it can stimulate the imagination before the whole thing turns to madness. So intense and vivid a life that a man literally divides himself into two people. He takes wing and he quite genuinely wanders wherever he feels inclined to go. His home, his father, mother, family, his childhood – all the various stages of his life. And then even more, there are all those castles in Spain that appear in his fertile mind with such an unbelievable vividness that he really comes to believe that he is living through everything that he dreams.

Thirty-six years have passed, and yet recording everything that came into my head at that moment of my life does not need the slightest effort.

No: I should do the members of the jury no harm: my pen races along. But what about the prosecuting counsel? I must not miss him, not at any cost. In any case, I had a ready-made recipe for him, straight out of AlexAndré Dumas. Just like in The Count of Monte Cristo, and the guy they shoved into the cellar and let die of hunger.

As for that lawyer, yes, he was answerable all right. That red-robed vulture – there was everything in favour of putting him to death in the most hideous manner possible. Yes, that was what I should do: after Polein and the cops, I should devote my whole time to dealing with this creep. I’d rent a villa. It’d have to have a really deep cellar with thick walls and a very solid door. If the door wasn’t thick enough I should sound-proof it myself with a mattress and tow. Once I had the villa I’d work out his movements and then kidnap him. The rings would be all ready in the wall, so I’d chain him up straight away. And then which of us was going to have fun?

I had him directly opposite me: under my closed eyelids I could see him with extraordinary exactness. Yes, I looked at him just as he had looked at me in court. The scene was so clear and distinct that I could feel the warmth of his breath on my face; for I was very close, face to face, almost touching him. His hawk’s eyes were dazzled and terrified by the beam of a very powerful headlight I had focused on him. Great drops of sweat ran down his red, swollen face. I could hear my questions and I listened to his replies. I experienced that moment very vividly.

‘Do you recognize me, you sod? I’m Papillon. Papillon, the guy you so cheerfully sent down the line for life. You sweated over your books for years and years so as to be a highly educated man; you spent your nights doing Roman law and all that jazz; you learnt Latin and Greek and you sacrificed your youth so as to become a great speaker. Do you think it was worth it? Where did it get you, you silly bastard? What did it help you do? To work out new, decent laws for the community? To persuade the people that peace is the finest thing on earth? To preach the philosophy of some terrific religion? Or even to use your influence, your superior college education, to persuade others to be better people or at least stop being wicked? Tell me, have you used your knowledge to pull men out of the water or to drown them? You’ve never helped a soul: you’ve only had one single motive – ambition! Up, up. Up the steps of your lousy career. The penal settlements’ best provider, the unlimited supplier of the executioner and the guillotine – that’s your glory. If Deibler3 had any sense of gratitude he’d send you a case of the best champagne every New Year. Isn’t it thanks to you, you bleeding son of a bitch, that he’s been able to lop off five or six more heads in the past twelve months? Anyhow, now I’m the one that’s got you, chained good and hard to this wall. I can just see the way you grinned, yes, I can see your triumphant look when they read out my sentence after your speech for the prosecution. It seems only yesterday, and yet it was years ago. How many? Ten years? Twenty?’

But what was happening to me? Why ten years? Why twenty? Get a hold on yourself, Papillon; you’re young, you’re strong, and you’ve got five thousand six hundred francs in your gut. Two years, yes. I’d do two years out of my life sentence, and no more: I swore that to myself.

Snap out of it, Papillon, you’re going crazy. The silence and this cell are driving you out of your mind. I’ve got no cigarettes. Finished the last yesterday. I’ll start walking. After all, I don’t have to have my eyes closed or my handkerchief over them to see what goes on. That’s it; I’m on my feet. The cell’s four yards long from the door to the wall – this is to say five short paces. I began walking, my hands behind my back. And I went on again, ‘All right. As I was saying, I can see your triumphant look quite distinctly. Well, I’m going to change it for you: into something quite different. In one way it’s easier for you than it was for me. I couldn’t shout out, but you can. Shout just as much as you like; shout as loud as you like. What am I going to do to you? Dumas’ recipe? Let you die of hunger, you sod? No: that’s not enough. To start with I’ll just put out your eyes. Eh? You still look triumphant, do you? You think that if I put your eyes out at least you’ll have the advantage of not seeing me any longer, and that I’ll be deprived of the pleasure of seeing the terror in them. Yes, you’re right: I mustn’t put them out. At least not right away. That’ll be for later. I’ll cut your tongue out, though, that terrible cutting tongue of yours, sharp as a knife; no, sharper – as sharp as a razor. The tongue that you prostituted to your splendid career. The same tongue that says pretty things to your wife, your kids and your girl-friend. Girl-friend? Boy-friend, more likely. Much more likely. You couldn’t be anything but a passive, flabby pouffe. That’s right: I must begin by doing away with your tongue, because next to your brain that’s what does the damage. You see it very well, you know: so well you could persuade the jury to answer yes to the questions put to them. So well that you could make the cops look like they were straight and devoted to their duty: so well that that witness’s cock and balls seemed to hold water. So well that those twelve bastards thought I was the most dangerous man in Paris. If you hadn’t possessed this false, skilful, persuasive tongue, so practised at distorting people and facts and things, I should still be sitting there on the terrace of the Grand Cafe in the Place Blanche, and I’d never have had to stir. So we’re all agreed, then, that I’m going to rip this tongue of yours right out. But what’ll I do it with?’

I paced on and on and on. My head was spinning, but there I was, still face to face with him, when suddenly the electricity went out and a very faint ray of daylight made its way into the cell through the boarded window.

What? Morning already? Had I spent the whole night with my revenge? What splendid hours they had been! How that long, long night had flown by!

Sitting on my bed, I listened. Nothing. The most total silence. Now and then a little click at my door. It was the warder, wearing slippers so as to make no sound, opening the little metal flap and putting his eye to the peep-hole that let him see me without my being able to see him.

The machinery that the Republic of France had thought up was now entering its second phase. It was working splendidly: in its first run it had wiped out a man that might be a nuisance to it. But that was not enough. The man was not to die too quickly: he mustn’t manage to get out of it by way of suicide. He was wanted. Where would the prison service be if there weren’t any prisoners? In the shit. So he was to be watched. He had to go off alive to the penal settlements, where he would provide a living for still more state employees. I heard the click again, and it made me smile.

Don’t you worry, you sod: I shan’t escape. At least not the way you’re afraid of – not by suicide. There’s only one thing I want, and that’s to keep alive and as fit as possible and to leave as soon as I can for that French Guiana where you’re sending me, bloody fools that you are: thank God.

This old warder with his perpetual clicking was a fairy godmother in comparison with the screws over there: they were no choir-boys, not by any means. I’d always known that; for when Napoleon set up the penal settlements and they said to him. ‘Who are you going to have to look after these hard cases?’ he answered, ‘Harder cases still.’ Afterwards I found that the inventor of the penal settlements had not lied.

Clang clang: an eight-inch-square hole opened in the middle of my door. They passed me in coffee and a pound and a half of bread. Now I was sentenced I was no longer allowed to have things sent in from the restaurant, but if I could pay I could still buy cigarettes and a certain amount of food from the little canteen. That would last a few days more, then after that nothing. The Conciergerie was the stage just before penal internment. I smoked a Lucky Strike, enjoying it enormously: six francs sixty a packet they cost. I bought two. I was spending my official prison money because soon they would be confiscating it for the costs of the trial.

Dega sent a little note in my bread to tell me to go to the de-lousing centre. ‘There are three lice in the matchbox.’ I took out the matches and I found his fine healthy cooties. I knew what it meant. I showed them to the warder so that the next day he should send me and all my things, including the mattress, to a steam-room where all the parasites would be killed – except us, of course. And there the next day I met Dega. No warder in the steam-room. We were alone.

‘You’re a good guy, Dega. Thanks to you I’ve got my charger.’

‘It doesn’t bother you?’

‘No.’

‘Every time you go to the latrine, wash it well before you put it back.’

‘Yes. I think it’s completely water-tight. The folded notes are perfect, though I’ve had it in this last week.’

‘That means it’s all right, then.’

‘What do you think you’ll do, Dega?’

‘I’m going to pretend to be mad. I don’t want to go to Guiana. I’ll do maybe eight or ten years here in France. I’ve got contacts and I can get five years remission at least.’

‘How old are you?’

‘Forty-two.’

‘Then you’re out of your mind! If you do ten out of your fifteen you’ll come out an old man. Are you scared of penal?’

‘Yes. I’m not ashamed of saying it to you, Papillon, but I’m scared. It’s terrible in Guiana. Eighty per cent mortality every year. One convoy takes the place of the last, and each convoy has between eighteen hundred and two thousand men. If you don’t get leprosy you get yellow fever or one of those kinds of dysentery there’s no recovering from, or else consumption or malaria. And if you escape all that then it’s very likely you’ll get murdered for your charger, or else you’ll die trying to make a break. Believe me, Papillon, I’m not trying to discourage you; but I’ve known a good many lags who’ve come back to France after doing short stretches – five to seven years – and I know what I’m talking about. They are absolute complete bleeding wrecks. They spend nine months of the year in hospital; and they say that making a break is nothing like what people think – not a piece of cake at all.’

‘I believe you, Dega. But I believe in myself, too. I won’t waste much time there. That’s something you can be sure of. I’m a sailor and I understand the sea, and you can trust me when I say I shall make a break very soon. And what about you? Can you really see yourself doing ten years hard? Even if they do give you five off, which is not at all sure, do you really think you could do it without being driven crazy by the solitary? Take me now, all alone in that cell with no books, no going out, no being able to talk to anyone twenty-four hours every god-damned day – it’s not sixty minutes you have to count in each hour but six hundred: and even then you’re far short of the truth.’

‘Maybe. But you’re young and I’m forty-two.’

‘Listen, Dega, tell me straight: what is it you’re scared of most? The other lags, isn’t it?’

‘To tell you straight, Papi, yes it is. Everyone knows I’m a millionaire, and there’s no distance between that and cutting my throat because they think I’m carrying fifty or a hundred thousand on me.’

‘Listen, do you want us to make a pact? You promise me not to go crazy and I’ll promise to keep right next to you all the time. Each can support the other. I’m strong and I move quick: I learnt how to fight when I was a kid and I’m terrific with a knife. So as far as the other lags are concerned you can rest easy: we’ll be respected, and more than that we’ll be feared. As for the break, we don’t need anyone else. You’ve got cash, I’ve got cash: I know how to use a compass and I can sail a boat. What more do you want?’

He looked at me hard, right in the eye … We embraced one another. The pact was signed.

A few moments later the door opened. He went off with his pack in one direction and I in the other. We were not very far apart and we saw one another from time to time at the barber’s or the doctor’s or in chapel on Sundays.

Dega had been sent down for the business of the phony National Defence bonds. A bright forger had produced them in a very unusual way: he bleached the five hundred franc bonds and overprinted them with the ten thousand franc text, absolutely perfectly. As the paper was the same, banks and businessmen accepted them just like that. It had been going on for years and the government’s financial section was all at sea until the day they picked up a character named Brioulet – caught him red-handed.

Louis Dega was sitting there calmly, keeping an eye on his bar in Marseilles, where the pick of the southern underworld came every night and where the really hard guys from all over the world met one another – an international rendezvous. That was 1929 and he was a millionaire. Then one night a young, pretty, well-dressed woman turned up. She asked for Monsieur Louis Dega.

‘That’s me, Madame. What can I do for you? Come into the next room.’

‘Look, I’m Brioulet’s wife. He’s in Paris in prison for passing forged bonds. I saw him in the visiting-room at the Santé: he gave me the address of this bar and told me to come and ask you for twenty thousand francs to pay the lawyer.’

It was at this point, faced with the danger of a woman who knew his part in the business, that Dega, one of the most esteemed crooks in France, made the one remark he never should have made. ‘Listen, Madame, I don’t know your husband from Adam, and if you need money, go on the streets. You’re young and pretty and you’ll make more than you need.’ Furious, the poor woman ran out in tears. She told her husband. Brioulet was mad and the next day he told the investigating magistrate everything he knew, directly accusing Dega of being the man who produced the forged bonds. A team of the most intelligent detectives in the country got on to Dega’s trail. One month later Dega, the forger, the engraver and eleven accomplices were all arrested at the same moment in different places and put behind bars. They came up at the Seine Assizes and the trial lasted fourteen days. Each prisoner was defended by a famous lawyer. Brioulet would never take back a single word. And the result was that for a piddling twenty thousand francs and a damn-fool crack the biggest crook in France got fifteen years hard labour. There he was, ten years older than his age, and completely ruined. And this was the man I had just signed a treaty with – a life and death pact.

Maître Raymond Hubert came to see me. He wasn’t very pleased with himself. I never uttered a word of blame.

One, two, three, four, five, about turn … One, two, three, four, five, about turn. It was a good many hours now that I had been walking up and down between the door and the window of my cell. I smoked: I felt I was well in control, steady-handed and able to cope with anything at all. I promised myself not to think about revenge for the time being. Let’s leave the prosecuting counsel just there where I left him, chained to the rings in the wall, opposite me, without yet making up my mind exactly how I’d do him in.

Suddenly a shriek, a desperate, high-pitched, hideously dying shriek made its way through the door of my cell. What was it? It was like the sound of a man under torture. But this was not the Police Judiciaire. No way of telling what was going on. They turned me right up, those shrieks in the night. And what strength they must have had, to pierce through that padded door. Maybe it was a lunatic. It’s so easy to go mad in these cells where nothing ever gets through to you. I talked aloud there all by myself: I said to myself what the hell’s it got to do with you? Keep your mind on yourself, nothing but yourself and your new side-kick Dega. I bent down, straightened up and hit myself hard on the chest. It really hurt: so everything was all right – the muscles of my arms were working perfectly. And what about your legs, man? You can congratulate them, because you’ve been walking more than sixteen hours now and you’re not even beginning to feel tired.

The Chinese discovered the drop of water that falls on your head. The French discovered silence. They do away with everything that might occupy your mind. No books, no paper, no pencil: the heavily-barred window entirely boarded up: only a very little light filtering through a few small holes.

That piercing shriek had really shaken me, and I went up and down like an animal in a cage, I had the dreadful feeling that I had been left there, abandoned by everybody, and that I was literally buried alive. I was alone, absolutely alone: the only thing that could ever get through to me was a shriek.

The door opened. An old priest appeared. Suddenly you’re not alone: there’s a priest there, standing in front of you.

‘Good evening, my son. Forgive me for not having come before, but I was on holiday. How are you?’ And the good old curé walked calmly into the cell and sat right down on my pad. ‘Where do you come from?’

‘The Ardèche.’

‘And your people?’

‘Mum died when I was eleven. Dad was very good to me.’

‘What did he do?’

‘School-teacher.’

‘Is he alive?’

‘Yes.’

‘Why do you speak of him in the past if he is still alive?’

‘Because although he’s alive all right, I’m dead.’

‘Oh, don’t say that! What did you do?’

In a flash I thought how square it would sound to say I was innocent: I replied, ‘The police say I killed a man; and if they say it, it must be true.’

‘Was it a tradesman?’

‘No. A ponce.’

‘And they’ve sentenced you to hard labour for life for something that happened in the underworld? I don’t understand. Was it murder?’

‘No. Manslaughter.’

‘My poor boy, it’s unbelievable. What can I do for you? Would you like to pray with me?’

‘I never had any religious instruction. I don’t know how to pray.’

‘That doesn’t matter, my son: I’ll pray for you. God loves all His children, whether they are christened or not. Repeat each word as I say it, won’t you?’ His eyes were so gentle, and such kindness beamed from his round face that I was ashamed to refuse; and as he had gone down on his knees I did the same. ‘Our Father which art in heaven …’ Tears came into my eyes: the dear priest saw them and with his plump finger he gathered a big drop as it ran down my cheek. He put it to his mouth and drank it. ‘My son,’ he said, ‘these tears are the greatest reward God could ever have sent me today, and it comes to me through you. Thank you.’ And as he got up he kissed me on the forehead.

We sat there, side by side on the bed again. ‘How long is it since you wept?’

‘Fourteen years.’

‘Why fourteen years ago?’

‘It was the day Mum died.’

He took my hand in his and said, ‘Forgive those who have made you suffer so.’

I snatched it away and sprang into the middle of my cell – an instinctive reaction. ‘Not on your life! I’ll never forgive them. And I’ll tell you something, Father. There’s not a day, not a night, not an hour or minute when I’m not busy working out how I’ll kill the guys that sent me here – how, when and what with.’

‘You say that, my son, and you believe it. You’re young, very young. As you grow older you’ll give up the thought of punishment and revenge.’ Thirty-four years have passed now, and I am of his opinion. ‘What can I do for you?’ asked the priest again.

‘A crime, Father.’

‘What crime?’

‘Going to cell 37 and telling Dega to get his lawyer to ask for him to be sent to the central prison at Caen – tell him I’ve done the same today. We have to get out of the Conciergerie quick and leave for one of the centrals where they make up the Guiana convoys. Because if you miss the first boat you have to wait another two years in solitary before there’s another. And when you’ve seen him, Father, will you come back here?’

‘What reason could I give?’

‘You could say that you forgot your breviary. I’ll be waiting for the answer.’

‘And why are you in such a hurry to go off to such a hideous place as the penal settlement?’

I looked at him hard, this great-hearted salesman of the good word, and I was certain he would not betray me. ‘So as to escape all the sooner, Father.’

‘God will help you, my boy, I am sure of it; and I feel that you will remake your life. I can see in your eyes that you are a decent fellow and that your heart is in the right place. I’ll go to cell 37 for you. You can expect an answer.’

He was back very soon. Dega agreed. The curé left me his breviary until the next day.

What a ray of sunlight that was! Thanks to that dear good man my cell was filled with it – all lit up. If God exists why does He allow such different sorts of human being on earth? Creatures like the prosecuting counsel, the police, Polein – and then this chaplain, the chaplain of the Conciergerie?

That truly good man’s visit set me up, healed me: and it was useful, too. Our requests went through quickly and a week later there we were, seven of us lined up in the corridor of the Conciergerie at four in the morning. All the screws were there too, a full parade.

‘Strip!’ Everybody slowly took off his clothes. It was cold and I had goose-pimples.

‘Leave your things in front of you. About turn. One pace backwards.’ And there in front of each of us was a heap of clothes.

‘Dress yourselves.’ The good linen shirt I had been wearing a few moments earlier was replaced by a rough undyed canvas job and my lovely suit by a coarse jacket and trousers. No more shoes: instead of them I put my feet into a pair of wooden sabots. Up until then I’d looked like any other ordinary type. I glanced at the other six – Jesus, what a shock! No individuality left at all: they had turned us into convicts in two minutes.

‘By the right, dress. Forward march!’ With a escort of twenty warders we reached the courtyard and there, one after another, each man was shoved into a narrow cupboard in the cellular van. All aboard for Beaulieu – Beaulieu being the name of the prison at Caen,