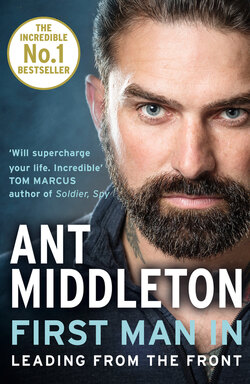

Читать книгу First Man In - Ant Middleton, Ant Middleton - Страница 6

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеOf all the people that I meet in my day-to-day life, most don’t have the courage to ask The Question. The majority only know me from the television and so are aware that I served two tours of Afghanistan with the Special Forces. Because my first TV appearance was on Channel 4’s SAS: Who Dares Wins, it’s often assumed that I was a member of the Special Air Service. In fact, I was a Special Boat Service operator. In military parlance I was a point man. My job was to lead a small group of men into Taliban compounds, searching out high-status targets on dangerous ‘hard arrest’ missions. Because of the great secrecy that surrounds Special Forces operations, I can’t talk about them. But I am able to give you a very general answer to The Question.

Killing someone feels like gently pulling your trigger finger back a few millimetres. It feels like hearing a dull pop. It feels like seeing a man-shaped object fall away from your sights. It feels like getting the job done. It feels satisfying. But, beyond that, killing someone feels like nothing at all. You might find that shocking. You might even find it offensive. I’m aware, of course, that mine is not an ordinary response. It’s not even a response that I share with everyone who’s fought in war. Many brave men I served alongside will remain forever traumatised by the horrors they’ve witnessed and taken part in. I truly feel for them. Being part of a ‘hard arrest’ team meant working regularly in conditions of life-threatening stress and being surrounded, almost every day, by blood and killing. But my struggle wasn’t with the trauma all that created. Mine was with its satisfaction. I’d enjoyed it – perhaps, at times, too much. I thrived on combat. I still miss it every day.

In Afghanistan, getting shot at was a regular occurrence. You came to expect it. I viewed survival as a numbers game. As point man, every time I entered a Taliban compound or a room within a compound and knew that there was badness on the other side, I played the odds in my head. It was a bit like roulette – a calculated risk. I’d think, ‘What are the chances of me going through that door and there’s a combatant there who knows I’m coming? If they do know I’m coming, what are the chances of them being able to fire more than one bullet before I shoot at them? What are the chances that one bullet’s going to hit me in the head and kill me?’ When I thought of it like that, I’d usually come to realise the chances were pretty slim. So I’d think, ‘Fuck it, the odds are with me,’ and that would get me through the door.

Sometimes, at this point of entry, there’d be bullets flying in my direction. But experience told me these bursts were usually over in seconds and that the moment there was a pause in firing I could make my move – entering crouched low, because idiots with AKs usually can’t control the natural lift of their weapons and they spray rounds at the ceiling when they fire. I’d think, ‘If he pulls the trigger again, he’ll only have the chance to squeeze it once or twice, max, before I get the drop on him.’ If one or two rounds did come out of his weapon and strike me in the chest plate, it would only be my chest plate. If they hit me in the leg, they’d only immobilise me for a split second. If I fell down, I knew my pal would be right behind me, on my shoulder, and would finish the job in a blink. That was how I saw it – a numbers game. Always the odds. Always a little calculation in my head.

Which is not to say I found it easy. Far from it. Going into an operation, the fear would be horrendous. But as soon as it all began – the moment I breached the compound or made contact with the enemy – I’d enter a completely different psychological space. The only thing I can compare it to is the final seconds before a car smash, when you see how it’s all going to play out in slow motion. Your brain goes into a hyper-efficient state, absorbing so much information from your surroundings that it really does feel as if the clock has suddenly slowed down – as if you’ve got the ability to control time itself.

This enabled me to act with a level of precision in which it seemed I could count in milliseconds. It was a state of pure focus, pure action, pure instinct, every cell in my body working in perfect harmony with each other towards the same end, at a level of peak performance. I didn’t feel any emotion. There was only awareness, control and action. It was the closest thing I could imagine to feeling all-powerful, like God. And that’s what I was, in a way. When I was point man in the middle of a dangerous operation, godlike was how my mind and body felt – and godlike was how I had to act in judging, in a fraction of an instant, who lived and who died.

The first man I ever killed came out at me from the hot, dusty shadows of an Afghan compound. It was night. He was wearing a traditional white ankle-length robe, called a dish-dash. There was a thick strap over his right shoulder. In his hands, an AK-47. He stopped, then squinted into the darkness. He couldn’t see me. He stared some more. His neck craned forwards. He saw the two green eyes of my night-vision goggles staring back at him from the blackness. And then it came, an event I’d soon know well. While a lot goes on within it, the moment of death always has an order, a sure sequence of events. It happens like this: Shock. Doubt. Disbelief. Confusion. Your target feels an urge to double-check a situation that they can’t quite believe is happening. Their thoughts race. Their lips open just a few millimetres. Their eyes squint into the night. Their chin moves forward. Their body begins to change its stance. And then …

That moment – the one I’d watch happening time after time after time in Afghanistan in intimate, ultra-slow motion – is our secret weapon. Staying alive, and achieving our objective, relied on tiny fractions of time such as this. Special Forces soldiers are trained to operate between the tremors of the clock’s ticking hand, slipping in and out and doing their work in the time it takes for the enemy to turn one thought into another. And that’s how it went the night of my first kill. From my position in the corner of the compound I took half a step forwards, raised my weapon and squeezed the trigger once, then twice. The suppressor I’d screwed to the barrel made the firing of the bullets sound like little more than the clicks of a computer mouse. Perfect shots. Two in the mouth. He went down.

The Special Forces are looking for individuals who have the ability to do this as a job, day in, day out, and not let it destroy them. That was me. People like this aren’t born this way. They’re made. This book is not just lessons in leadership that I’ve learned over the years. It’s the story of how I became the man I am. It’s a tale of a naive and gentle young lad whose first memory is of his beloved father being found dead. It’s the tale of struggle and pain and fury in the army, of darkness and violence on the streets of Essex, of days in war zones, days in prison, days hunting down kidnapped girls in foreign lands, days leading men out of impossible hells. It’s the story of how I became the kind of individual who leads from the front and who, no matter what danger he’s charging into, always wants to be first man in.