Читать книгу Cops and Robbers: The Story of the British Police Car - Ant Anstead, Ant Anstead - Страница 5

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеI am hugely proud of my police career, and when I look back on the years that I spent as a police officer I do so with a great sense of pride and achievement, knowing that I played a small part in what I firmly believe to be the best police service in the world; an institution that puts the great into Great Britain.

Like any typical teenager, in my youth I never really knew what I wanted to do when I was older, except that I didn’t want to follow my father into the hospitality sector. I was the second oldest of four boys; my two younger brothers were still at school, but my older brother was working as a scaffolder on building sites. I would often join him at weekends to earn extra pocket money, which I blew on car parts for the numerous classic cars I was restoring and selling from home. I had an auntie in the police, though, who was cool and I looked up to her, so I started to research joining the police. At 18 and a half I was just old enough to apply. I never told anyone what I was doing, and it was only in the week that I was packing my bags to go to police college that I told my parents of my chosen career. I was young and full of enthusiasm, and I developed a passion for the law. I loved being within the police family and still consider myself, somehow, part of that; l look back on that section of my life with great affection.

Being a police officer also taught me a lot, much of which I was able to use once I left the service, and that knowledge has given me a great sense of perspective. At the age of 23 I became one of the UK’s youngest armed officers and a full-time member of the TFU (Tactical Firearms Unit). I hold two commendations for bravery and I can recall countless incidents that took my breath away with either fear, laughter, tears or amazement. I look back at those dangerous incidents now in a positive way, as moments of great luck, and I still have the scars from them, which remind me how lucky I am. I owe a lot to the police and I am grateful for the years I spent with them. It helped me to mature, and I have the utmost respect, admiration and affection for my fellow officers.

The police service in the UK is truly a service. I think of it as a service for the people of the nation, which was the original aim, unlike in many other countries where police work has a different ethos. The police taught me about self-discipline, gave me a work ethic and, I’d like to think, some empathy (after all, the best coppering is not always about arrests or box ticking). Also, it taught me, perhaps less usefully in civilian life, firearms training. I learned how to deal with people in all different circumstances. I became fascinated by human behaviour and I use all that learning today in a positive way in my own life. People often ask me if I get nervous hosting live television to millions of viewers, and I simply say ‘No. I’ve had a gun pointed at my face, this is easy’.

Our framework of laws and the ability to enforce them is what makes modern civilised society function – without this we would have no hospitals, roads or even an economy in which to find useful work. The police are the bedrock of a civilised society; we need them in order to function and make our world bearable. We hope we never need them, or meet them, yet we feel reassured that they are there just in case. A great deal of police work goes under the radar because proper policing isn’t shouted about, it mops up the bad in favour of the good. My tutor, Terry Walker, who was about to retire after 30 years’ service when I joined, taught me about humanity and caring for the public that we aimed to protect. I joined in 1999, at a time when he had seen the worst of people during a changing police service that meant officers had to adapt too. Terry always wore his helmet, never carried a baton, never raised his voice and never asked for anything in return. He was an old-school gentleman. I remember him fondly.

I carried with me into the police a great affliction. I was a petrol-head, and the truth is I always have been. From my days pushing Corgi toys around the carpet as a four-year-old, I turned to Lego as a boy and at the age of 14 made my own go-kart from a lawnmower I bought at a flea market. I paid £2 and dragged it the three miles home before taking it apart and putting the engine into a wooden chassis. I never did get it working. I built my first car when I was 16 and bought a vermillion orange MG Midget the moment I passed my test at 17. Cars were where it was at for me. At an early age I was totally and utterly besotted with the looks, sounds, smells and shapes of cars. I had it bad! I could recognise every car on the road and I yearned to drive them. In fact, it was the cars used in police dramas on TV that also helped steer me into policing – who doesn’t love Bodie and Doyle handbrake-turning a Capri (see chapter fifteen on film/TV police cars) and who wouldn’t want to be them when you are 12 years old? I certainly did.

The British police’s relationship with the car and the motorist has at its very heart a central issue that is both contradictory and conflicting. When policing and motoring were both in their nascent stages, PCs were set to catch this new breed of people, the motorists, who were terrorising horses and the public with their frightening and, frankly, it seemed, death-defying 15mph machines. Horseless carriages (the term ‘car’ did not catch on until the early twentieth century) would be an increasingly common feature of UK life for some years before the police started thinking about using them as tools themselves.

Since then the, car has become essential to everyday life. However, it has also become a source of friction between the police and the public. Think about it; if you get burgled or attacked, the police action in catching the criminal and putting them behind bars is supported by 99.9 per cent of the public, but if a traffic cop pulls someone over for doing 83mph on the M1 at 3am, that person is quite likely to feel aggrieved, even though they have, pure and simple, broken the law, just as a shoplifter has. Society’s attitudes still mean that the speeding driver is quite likely to moan about the police to their friends and family, or even on social media, in a way that would be unacceptable for a burglar or mugger, almost as if motoring offences are kind of accepted. The number of times I pulled a car over and I was met with ‘Have you not got anything better to do?’ was alarming. And I’ll let you into a secret. The police feel some sympathy with that, too, because most cops love cars!

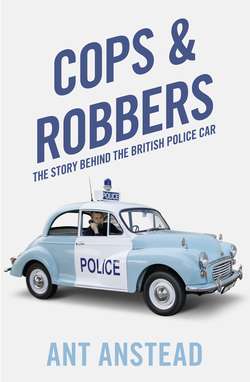

Motoring, whether it’s dealing with driving offences or clearing up accidents, represents the vast majority of UK police interaction with the public and is the biggest cause of friction, too. Yet deep down everyone loves a police car, even when they have been done for speeding! Whether it’s a Wolseley cornering on its door handles at 25mph, a Senator spearing down a motorway, or a Morris Minor Panda, the cars used by the police take on a special quality, so much so that countless enthusiasts collect model police cars in different liveries and particular legendary police cars have become part of the nation’s shared consciousness.

That love for the police car and the men and women who drive them is exactly what this book investigates and celebrates.

And, like many people today, I share that love affair with the Great British police car.