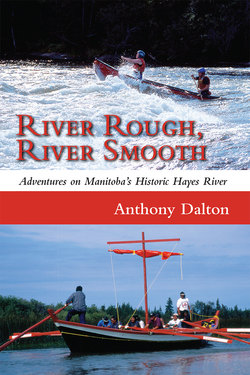

Читать книгу River Rough, River Smooth - Anthony Dalton - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1 Rowing Down the River

There is no place to get to know companions more intimately than in a small craft on a voyage.

— Tristan Jones (1929–1995), To Venture Further

“AHA, BOYS! OHO, BOYS! Come on, boys! Let’s go, boys!” Ken McKay’s rich voice echoed down the wilderness river. A few crows took alarm. They cawed their disapproval and launched themselves skywards, flapping shiny, black wings urgently away from the intrusive cries. As Ken’s words reverberated off the smooth, granite boulders on either side, eight strong backs bent over long, slim oars. Before his command had been completed, sixteen tired arms picked up the tempo. An equal number of legs braced against any solid object as dozens of muscles took up the strain. Eight oars sliced into the river as one.

Directly in front of me, Wayne Simpson’s red oar blade bit deeply into the cold water, ripped through it, and burst up into the warmer air. Sparkling drops of the Hayes River spilled in a cascade of miniature jewels behind it. Without hesitation, the oar plunged to the river again to complete the cycle: and then to start all over again. For once oblivious to my surroundings, I followed, forcing my oar to mimic the one in front.

Wayne had been rowing regularly for much of the summer on Playgreen Lake, beside Norway House. I had enjoyed little recent practice. He was twenty-seven. I was fifty-four. The age difference was uncomfortably obvious, especially to me. My arms felt like lead as I fought to maintain his rhythm. Drop the blade into the river, force back hard, and lift out again. Into the river, force back hard, and lift out again. Over and over the brief monotonous cycle was repeated. My eyes focused on a point in the middle of Wayne’s powerful shoulders, just below the collar of his white T-shirt, where the manufacturer’s oblong label showed vaguely through the material. As he moved back, pulling hard on the oar, so I pulled back at the same time, desperately trying to keep time by maintaining a constant distance between my eyes and that arbitrary spot on his shirt.

I rarely took a seat at the oars. My job was photography and writing the expedition log. Cameras and oars are not compatible when used by one man at the same time. For the moment my cameras were safely stowed near my feet. Shutter speeds and apertures were far from my mind. Determined to row as hard and for as long as those around me; forcing myself not to be the first to rest his oar, I allowed my mind to slide into a different realm. Think rhythm. Think Baudelaire.

Bau-del-aire. Three short syllables. One for the blade’s drop into the river. Another for the pressure against living water. The third — just as it sounds, I told myself — back into the air. Bau-del-aire. Bau-del-aire. Bau-del-aire.

Allons! Allons! Allons! 1 (Let’s go on! Let’s go on! Let’s go on!)

My rowing rhythm improved a little with the beat in my head. Subconsciously, silently, I recited the sensual lines from my favourite parts of Baudelaire’s “Le Voyage”:

Chaque îlot signale par l’homme de vigie Est un Eldorado promis par le Destin; L’Imagination qui dresse son orgie Ne trouve qu’un récif aux clartés du matin. 2

My lips moved repetitiously, mimicking each thrust of my oar — pulling me and my pain along with the boat.

Sweat soaked my cap, saturating it until its cloth could hold no more. A rivulet escaped and trickled down my temple, followed by a flood that rolled from the top of my head, down my brow, and poured into my eyes. The salt stung and I blinked furiously to clear my vision; to maintain eye contact with that spot on Wayne’s shirt. The passing scenery — the banks of the Hayes River — was a blur of green and grey. I wondered how Baudelaire had fared on his long sea voyage to and from India in the 1840s.3 I was sure he had travelled in far greater comfort than we, the York boat crew.

Beside me, to my left, Simon grinned and grunted with the exertion. Behind us, toward the front of the boat, five other rowers bent to the task. The York boat leapt forward, creating a sizeable bow wave. Ken looked steadfastly ahead. His eyes, hidden as usual behind dark glasses, betrayed no thoughts: the copper skin of his face an expressionless mask. Both of his hands firmly gripped the long steering sweep. In the canoe, close by our stern, but off to starboard a little, Charlie and Gordon kept pace with us, their outboard motor purring softly.

Charlie called out to the rowers in encouragement; his powerful voice driving us to greater effort. We responded and dug deeper, into ourselves, and with the oars. The physical efforts of the previous weeks had been worthwhile. The rowers worked as a team, concentrating on a steady rhythm. As long as I followed Wayne’s fluid movements, I knew I could keep up with the others.

We all knew there were more rapids ahead, more dangers; more hard work. McKay’s often-heard cries of tempo change, “Aha, boys! Oho, boys!” were designed to break the tedium of long hours on the rowing benches, as well as to increase speed. Sudden spurts of acceleration tended to force the adrenaline through all our bodies, whether we were rowing or not. We would need that extra drive to negotiate the whitewater rapids and semi-submerged rocks still to come.

We were alone on the river. Our last contact with people was back at Robinson Portage, on the first night of that back-breaking overland traverse. Since then the river, the granite cliffs, and the forests of spruce, tamarack, and lobstick pine on either side, had been ours and ours alone. Briefly our passing touched both as we, twelve Cree, one outsider, a York boat, and a canoe rambled onward toward the sea.

Behind us stretched an invisible trail of defeated rapids. All, in some way or other, attempted to block our progress. Some almost succeeded, for a while. A few, wilder than others, tried to dash our expedition hopes and our boat on sharp-edged rocks. So far all had failed, though we and the boat bore the scars of each and every successive encounter. Our hands were cracked and blistered. Arms and legs bore multiple cuts and bruises. As they healed they were replaced by fresh slashes and new contusions. We were destined to earn many more superficial injuries in the next day or so.

Less than two weeks before, I was in Winnipeg studying York boats and their history, while nursing slowly mending broken ribs — the result of a fall in the Swiss Alps two weeks prior. Now, with a long oar clamped in both hands, I pulled with all my might, the injured ribs all but forgotten. My eyes focused on Wayne’s shirt. My mind wandered away from Baudelaire, trying to recall half-forgotten lines from another poet’s classic prose.

Pilgrim of life, follow you this pathway. Follow the path which the afternoon sun has trod. 4

Rabindranath Tagore’s words sounded lonely — as lonely as I sometimes felt on the river, although I was constantly surrounded by people. A pilgrim of life following a river the afternoon sun was already preparing to leave. My pathway flowed against the sun. My progress determined not by a celestial body, but subject to the whims of the Cree. Where they go, I go.

During those few days in Winnipeg, I spent many long hours curled up in my hotel room with books, historical articles, and my notepads. The rest was good for my ribs and beneficial to my mind. I studied for hours each day.

The Hudson’s Bay Company (also referred to in this book as HBC), which controlled the Hayes River York boat and canoe freight route for over twenty decades, came into being in its earliest form in 1667 in London, England.5 A syndicate of businessmen,6 headed by Prince Rupert,7 formed the Company of Adventurers with the intention of exploiting the reportedly fur-rich lands, and possible mineral wealth, to the west of Hudson Bay.8

Nonsuch,9 the first vessel actively employed by the syndicate that would eventually become the Hudson’s Bay Company, was no leviathan of the seas. Carrying a crew of only eleven men, she stretched no more than fifty-three feet on deck (sixteen metres), ignoring the lengthy bowsprit. That’s only nine feet (2.75 metres) longer than the Norway House Cree York boat — an extremely small ship for the Atlantic crossing: little more than a cockleshell on the unpredictable and hazardous ice-choked waters of Hudson Strait and Hudson Bay. Nonsuch did not visit the Hayes River, or any other estuary or potential trading post site on the west side of the bay. Her exploratory voyage was intended to search for the Northwest Passage route to the South Seas and to trade with the Indians. Ice conditions in the northern half of the bay sent the small ship due south from Hudson Strait into James Bay, the large inlet at the foot of Hudson Bay. There, Captain Zachariah Gillam10 and fur-trade guide Médart Chouart, Sieur des Groseilliers11 established a trading post at the mouth of a river. The “house” they built, from logs caulked with moss, they named Charles Fort in honour of the English king.12 They named the river after Prince Rupert.

When Nonsuch returned to England in the autumn of the following year, the London Gazette announced:13

This last night came in here the “Nonsuch Ketch”, which having endeavoured to make out a passage by the North-West, was in those seas environed with Ice, which opposing her progress, the men were forced to hale her on shoar and to provide against the ensueing cold of a long Winter; which ending they returned with a considerable quantity of Beaver, which made them some recompence for their cold confinement.

The fur-trading success of the Nonsuch voyage immediately boosted interest in the Hudson Bay region. Building up to a small fleet of sailing ships, over the next few years the Company erected more trading forts along the shores of James Bay and began to look farther afield.

The departure of the second colonist transport from York Fort to Rock Fort in 1821, en route to the Red River Settlement. Their journey would be uphill all the way.

In 1684, the Hudson’s Bay Company built a new fort near the mouth of the Hayes River, on the west coast of the great bay. That first fort was badly placed. Being too close to the tidal surge of Hud–son Bay, it suffered from spring flooding. Subsequent moves found the ideal location a few kilometres upriver. Named York Factory,14 after the Duke of York, it grew in importance to become the Company’s headquarters in North America. From humble beginnings it expand–ed into a sizeable town with a burgeoning population of Europeans. Beside the fort the indigenous Cree set up their own village.

Conditions at York Factory, for both Europeans and Natives, were less than ideal. The local Cree were just more experienced at living in the wilderness. Both groups suffered unbearably cold winters during which the river and the bay froze solid. Snow ob–literated everything for months at a time. Game was scarce and the people, both European and Cree, went hungry. In contrast, when the short, damp summers finally warmed the land, the residents welcomed the temporary end of snow. Dense pods of beluga whales appeared in the estuary. Caribou herds roamed the mossy tundra. Ducks and geese returned from the south. A few black bears found their way to the coast and polar bears ambled in from the ice floes to help liven things up a little. The advent of summer also awakened the North’s greatest pest. One York Factory resident complained that there were only two seasons at York: winter and mosquitoes.15

The fur trade was the prime reason for York Factory’s presence and, indeed, for the Hudson’s Bay Company’s existence. That far-flung enterprise developed into an enormous organization.Through the wide-ranging explorations of the Company’s employees in their search for ongoing trade, and the resultant economic development, the Hudson’s Bay Company formed the backbone for the vast area of land that is now Canada. Even so, at the end of the eighteenth century, after being in existence for 133 years, the Company still had less than five hundred employees posted in North America. It did, however, have trading posts on James Bay, the west coast of Hudson Bay, and far inland; wherever the mighty rivers took the Company’s servants.16

The list of Hudson’s Bay Company personnel in those decades reads today like an historical catalogue of explorers and exploration. In no particular order, the following adventurers were on the employee roster at varying stages in the Company’s history. The list is a sample only and by no means complete, but most of these men would have known the Hayes River trade route well.

David Thompson17 became famous as a cartographer. His early maps were of inestimable value in the modern mapping of western Canada. Pierre Radisson and his brother-in-law, Médard Chouart, Sieur des Groseilliers, both extremely capable wilderness adventurers, were involved in the creation of the Company. Dr. John Rae,18 one-time chief factor of the Hudson’s Bay Company, was certainly the greatest explorer to roam and map the northern Canadian wilderness. Henry Kelsey,19 little more than a confident boy in his late teenage years on his first expedition, trekked inland from York Factory and spent two years exploring the prairies. Later he travelled to Hudson Bay to learn more of its northern limits. Aged explorer James Knight20 was a Company man. His expedition of 1719, also to northern Hudson Bay, ended in mystery and tragedy. And then there was Samuel Hearne,21 perhaps the best-known of them all. He would one day command Prince of Wales Fort, opposite present-day Churchill. Hearne undertook many spectacular journeys through the unknown tundra. Historian George J. Luste justifiably referred to Samuel Hearne as the “Marco Polo of the Barren Lands.”22

Thanks to these intrepid men, and a host of others, the Hudson’s Bay Company name became synonymous with the exploration of central and western Canada. For more than two hundred years the Company’s servants, both European and Cree, ventured along raging, tumbling rivers in search of profit and, sometimes, each other. One of those rivers, the mighty Hayes, became the fur-trade highway to the immensity of the interior lands. In the late twentieth century, a modern band of Cree, plus one Anglo-Canadian, prepared themselves to challenge the most important river in the Hudson’s Bay Company’s history.

The Hayes River stretches for hundreds of kilometres across Manitoba, flowing in a northeasterly direction. It is one of the few untouched major rivers in Canada.There are no hydroelectric dams, and only two settlements along its route — Norway House and Oxford House. In June 2006, the Hayes finally received its long-overdue classification as a Canadian National Heritage River.23 As such, it will be protected against incursion by commercial interests and joins a distinguished and growing list of more than forty great Canadian rivers now protected by the CHRS, Canada’s national river conservation program.24

Unlike the fur traders of a bygone era, there were no riches waiting at the end of the river for us. No tightly packed bales of furs stowed in the boat to be sold or traded. No factor waiting at York Factory to greet us and check our cargo. We were just thirteen late-twentieth-century voyageurs heading down river in search of adventure and hoping for a glimpse into the past.

One afternoon, during my brief stay in Winnipeg, I visited Lower Fort Garry. This national historic park was the early headquarters and residence of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s governor, George Simpson, and his wife, Frances. George Simpson was a Scottish businessman who became one of the Hudson’s Bay Company’s most influential executives. A tireless traveller, Simpson came to know all the HBC fur-trade routes intimately, including the Hayes River.25

Three original York boats are on display there, two in the open, one under cover. The covered boat is claimed to be the last working York boat, sent to the fort from Norway House in 1935. Like Governor George Simpson, that boat had experienced the Hayes River in all its moods. I leaned against the weathered, dry, grey wood of an aged hull and tried to imagine what the open boat’s voyages were like. With no cabin, or other form of shelter, rain would turn a hard journey into abject misery. The slightly raised stem and stern promised some protection from waves on the larger lakes. Otherwise, both crew and cargo were at the mercy of the elements.

Inside the museum, a well-arranged diorama showed, in words and pictures, some of the trials and tribulations faced by the early fur traders. Life for the York boat crews, especially on the long and often dangerous voyages between the Red River Settlement (present-day Winnipeg) and York Factory, had never been a picnic. I was soon to experience first-hand the beauty of the river’s setting, the dangers of the rapids, and the extreme physical effort required on the portages.

From Lower Fort Garry I took a side trip to the open-air maritime museum at Selkirk. Among the preserved lake and river steamers and the restored Winnipeg yawls, was another York boat. Built in 1967 by the members of HMCS Chippawa26 in Winnipeg as a Centennial project, the boat, although smaller, is almost identical in construction to Ken McKay’s boat.

A voice calls for water, bringing my mind to the present. A tin mug is passed from one to another, filled with cool, refreshing river water to soothe a parched throat. I’m immediately thirsty — the power of suggestion — and reach for my own mug while trying to maintain rhythm with one hand.

I met Ken McKay and Charlie in Winnipeg. They had driven down from Norway House for supplies and to meet me. They had doubts as to whether an outsider could keep up, or would fit in. I had my own concerns, yet had no wish to be rejected. It was interview time. Would I pass muster? Over coffee in a hotel restaurant, we discussed the forthcoming adventure.

“I have a difficult name so you can call me Charlie Long Name for short,” Charlie Muchikekwanape introduced himself with a smile and a flair that was to prove typical of his sense of humour and intelligence. In his mid-thirties, tall and solidly built, he sported a long, glistening, black ponytail tied back with a beaded thong. Ken, by contrast, was obviously closer to my age — though a few years younger. He was heavily built, with short, black, wavy hair. For an hour we discussed my background, the river, the York boat, and the book I planned to write. I had the impression that my many wilderness experiences in the Arctic, Africa, the Middle East, and elsewhere27 failed to move them. Their interest in me was solely based on how I would fare in their wilderness. They studied me as acutely as I studied them. They wondered about me. I wondered about them. We would be living and working close together for the next few weeks.

A traditional York boat at Lower Fort Garry near Winnipeg. Now weathered and grey, the boat is a perfect example of the Yorks that carried freight up and down the Hayes River.

York boats were Spartan — but spacious — and could carry considerably larger loads than even the biggest freight canoes.

A couple of days after meeting Ken and Charlie, I took an early-morning flight north over Lake Winnipeg to Norway House. Thick, threatening storm clouds were gathering along the southern edge of the lake, suggesting Winnipeg might be in for heavy rains. Thinking of the exposure in an open York boat, I hoped they would continue soaking the south and leave the north alone for a while longer.

We circled and climbed above the weather: the Perimeter Airlines pilot taking the prop-jet on the most comfortable route to our destination. Behind us, Winnipeg was lost to sight. Below us, Lake Winnipeg28 — at 24,387 square kilometres (9,416 square miles) in area and one of the largest lakes in the world — looked like an ocean. Ahead, the forested lands of lakes and rivers on the Canadian Shield, where settlements are few and far between, reached to and beyond the horizon. Within an hour we skimmed low over Little Playgreen Lake, dropped below treetop height and settled gently on the runway at Norway House. The adventure was about to begin.