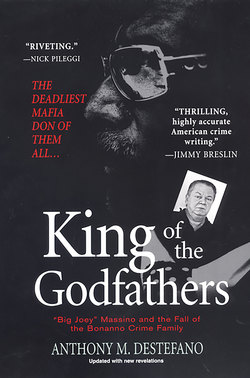

Читать книгу King of the Godfathers: - Anthony M. DeStefano - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 1 “No Sleep Till Brooklyn”

ОглавлениеHe knew they were coming.

As he walked the snow-crusted streets near his home in Howard Beach, Queens, on the night of January 8, 2003, the middle-aged man could sense the many pairs of eyes that followed his every move.

Street smart since leaving school in the eighth grade, he had acquired a finely tuned sense of when trouble was stalking him. Walking around on what was an unseasonably warm night along Cross Bay Boulevard with his youngest daughter, Joanne, the rotund grandfather had noticed cars he knew were those of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The sedans and the vans with tinted windows, the “bad cars” as he would say, had been around a lot recently. This night they shadowed him constantly.

He went to the Target department store and the cars were there. He went to the Cross Bay Diner and the cars were there. His daughter walked into Blockbuster Video and even she saw the cars.

Looking like Jackie Gleason with a big frame that carried 300 pounds and sporting a full head of graying hair, the old man whose grandchildren called him by the pet name Poppy had a habit of returning to his own place every evening. In his younger days, he might have spent the nights with his overeating friends. Lately, his high blood pressure and diabetes, as well as the toll of obesity, kept him closer to home. So when the agents parked at the end of the block and watched him enter the dark brick home on Eighty-fourth Street for the final time that day, they were certain he was in pocket for the night.

The agents would stick around until morning. It was standard operational procedure for the FBI just before a big arrest to make sure a target stayed in place no matter how long the surveillance team had to be on the street. Poppy was the kind of man they would take as much time as needed to make sure he was in the bag.

Poppy, the affable grand dad who delighted in belly flopping and swimming with neighborhood kids in his backyard pool on Eighty-fourth Street, was better known to law enforcement as Joseph Massino, born January 10, 1943, and branded with FBI number 883127N9. He was the secretive and elusive boss of the Bonanno crime family, the last American Mafia don of substance to be free on the streets. The Dapper Don was dead. The Chin and the Snake were in prison. But Massino had flourished.

A crafty and perceptive man who could be as gentlemanly as he could be vicious, Massino was a throwback to an era when Mafia leaders acted like patricians rather than ill-bred street thugs that had come to symbolize the public face of organized crime. Yet, Massino was not above having blood on his hands—lots of blood if truth be told—and in a few hours that dark side would change his life forever.

In terms of FBI tradecraft, putting someone to bed in the way the agents monitored Massino that night was an example of a crucial surveillance ritual that preceded an arrest. Seeing the subject enter a home and not leave allowed the next day’s arrest team to know with certainty that the person who was to be apprehended was at a particular place when the warrant was to be served. By midnight, Massino was at his faux Georgian-style home. The agents outside the house sat in their car at the location, fortifying themselves with cups of coffee and donuts from the Dunkin’ Donuts a few blocks away.

Surveillance duty is usually given to newly minted agents fresh out of the FBI Academy in Quantico, Virginia. It is a way for the new agents to learn the geography of a place like New York City while at the same time making observations of people and places that might prove crucial in some investigation months or even years down the road. Any observation, even those made at a distance so great that nothing could be overheard, might prove important if it later corroborated something a witness might say in court or to a grand jury.

Special Agents Kimberly McCaffrey and Jeffrey Sallet had done their share of surveillance drudgery when they joined the FBI some years earlier. But early on January 9, 2003, the two agents had a different task. Dressed in dark blue raid jackets that were embossed with the large yellow letters that spelled out “FBI,” McCaffrey and Sallet exited an official government sedan and walked up the front walk on Eighty-fourth Street. Accompanying them were three other law enforcement officials—an Internal Revenue Service agent, a state police officer, and another FBI agent.

The IRS agent made his way stealthily around the back of the house, taking care to avoid the covered swimming pool. McCaffrey and Sallet led the others up the walkway. The morning was chilly and at 6:00 A.M. the neighborhood was quiet.

McCaffrey rang the door bell. It might have been early but it was Massino, his hair neatly combed and fully dressed in a black pullover and large-sized sweat pants, who opened the front door. It was at that very instant that the two FBI agents, who had been studying and watching Massino from a distance for over four years, finally came face to face with their quarry. Though his pasta belly and mirthful grin gave him a genial appearance, Massino had a gaze that could be penetrating, steely, and cold. It was a look that could pull you in and captivate with its strength. It could also scare you. Slightly arched eyebrows made him always look as though he were expressing surprise. Yet, on this particular morning, Joseph Massino was not surprised.

“How are ya,” he said.

He surveyed the agents and police arrayed on his doorstep and looked out at the black government sedan in front of his house. Since he had seen the other government vans in the neighborhood over previous days and had been arrested before, Massino knew that something was coming down. The numerous cars that had shadowed him the night before also added to his feeling of apprehension. After McCaffrey flashed her FBI credentials, Massino replied quickly, almost glibly.

“I was expecting you yesterday.”

McCaffrey, a diminutive woman whose dark hair, black eyes, and fair skin bespoke her Irish roots, had to chuckle at his bravado. Here was a man who was hijacking trucks in the 1970s, before she was even born, a killer who is said to have boasted about being a one-man killing machine. But she also knew he could be a gentleman, a charmer, and certainly there was no hint of him causing any trouble. He will go peacefully, McCaffrey thought.

So began the day that Joseph Massino, the boss of one of New York City’s five legendary Mafia families and “The Last Don,” left his home in Howard Beach to live courtesy of the U.S. government in jail for the rest of his foreseeable life. Massino’s wife of forty-two years, Josephine, a petite and stylish, titian-haired Sicilian, dressed in her pajamas and housecoat, could do little but watch stoically and tightlipped as her spouse walked down the front way toward the government car.

Josephine Massino had witnessed this trip into incarceration before when Massino had been arrested in the 1980s. It led to a wearying routine of jailhouse visits and uncertainty. In recent days, as her husband’s sense of apprehension grew, she felt her own anxiety mount. The timing couldn’t have been worse. She was expecting an important call that very day from her oncologist. She would have to face that without him.

It was more than just the presence of the government surveillance cars, long a common fixture in a neighborhood that was home to other gangsters, that had tipped Massino to impending trouble. Federal investigators had been snooping around Massino and his businesses for years and word had gotten back to him fairly quickly when subpoenas started landing around town.

Then there were the arrests. One by one FBI agents started picking off some of Massino’s old cronies. Frank Coppa was in prison on securities fraud charges when he found himself indicted again in October 2002 for extortion. That particular indictment allowed the FBI to cast its net wider and arrest a number of other Bonanno crime family members like Richard Cantarella, one of Massino’s captains and trusted aides.

Massino wasn’t touched in that roundup. But it was clear that the government investigation was making a concerted push against a crime family that had survived much of the earlier onslaughts of federal prosecutions that began in the mid-1980s. Massino knew from the tally of arrests in recent months that it was only a matter of time before someone from a circle of mobsters he had confided in over a four-decade career in La Cosa Nostra would weaken and deliver him to the government.

Compared to his one-time neighbor John Gotti, the flashy but disastrous boss of the Gambino crime family, and Vincent “the Chin” Gigante, the Genovese crime family boss (who dressed in a bathrobe and mumbled as he walked through Greenwich Village in Manhattan in a crazy act), Massino was a relatively unknown face of the Mafia. True, he had been indicted in big cases in the past—once for plotting some gangland murders in the early 1980s and again in 1985 for labor racketeering. He also had a few mentions in the news media, usually accompanying his arrests or occasionally in speculative newspaper stories about the inner workings of La Cosa Nostra.

But if he was a mystery to the public, Massino, through his skill in mob politics as well as the ability to earn money, made for a steady rise through the ranks of the mob. Unlike Gotti, who taunted law enforcement with illegal fireworks displays in Ozone Park every Fourth of July and liked being a celebrity, Joseph Massino remained low key and avoided the flashy Manhattan night life. He liked to pad around the house in terry cloth shorts and cotton t-shirts. He filed his tax returns on time and declared income as high as $500,000 some years. When the police or FBI talked with him, Massino acted like a gentleman. He seemed almost boring.

But he was crafty. Massino knew that law enforcement surveillance techniques had advanced so much that talking to anyone except in the most circumspect way was suicidal. Gotti, having felt secure in an apartment above his Mulberry Street social club in Little Italy, talked openly about the Gambino family crimes and didn’t dream that the FBI would have bugging devices in the room.

Yet hours of Gotti’s conversations intercepted on FBI bugs all but wrote the federal indictment that led to his conviction and life sentence for racketeering in 1992. Later investigations of the Genovese, Colombo, and Lucchese crime families also relied on mountains of wiretap evidence that made the job of prosecutors as easy as shooting fish in a barrel. The old Mafia may have become the stuff of legend and hit television shows like The Sopranos, but it had also become easy pickings for law enforcement.

Massino could not completely avoid wiretaps. One of Gotti’s close associates, Angelo Ruggiero, an overweight and compulsively talkative mobster, had been so indiscreet that FBI agents not only wiretapped his telephone but also planted a bug in the kitchen of his Cedarhurst, Long Island, home. Massino was caught on some of the tapes though not enough to get him in serious trouble. But it was a wake-up call for him about the pervasiveness of surveillance. After that, Massino kept his mouth shut and decreed that his name should never be used in conversations, particularly in places where there may be wiretaps or listening devices.

There were a few slips in that rule. Cantarella was once overheard speaking to an informant. He said that it was Massino, who he referred to as “Joe,” who helped him become a made member of the crime family. The informant was wearing a recording device at the time. But for the most part, Massino’s name was discreetly kept out of incriminating conversations: a tug on the earlobe was how someone signaled he was talking about Massino without invoking his name. As a result, federal agents like McCaffrey and Sallet had no tapes that captured Massino’s voice saying anything incriminating.

Sallet, a sandy-haired New Englander and diehard Red Sox fan whose crew cut made him look like a high school athletic coach, picked out a favorite CD and put it in the player. He might be an accountant, but Sallet was no nerd. He liked the Beastie Boys, a group of New York white rappers, and in the minutes before he had arrested Massino, he was listening to the last cut on the disc. The title of that song, “No Sleep Till Brooklyn,” had been quite appropriate under the circumstances. That was certainly going to be Joe Massino’s day.

It was to the sound of Generation X music of three white Jewish boys from upper-middle-class parents that the maroon Buick Regal with tinted windows carrying mafioso Massino headed out from the quiet residential block where he lived and made its way to the Belt Parkway for the trip west toward lower Manhattan and FBI headquarters. Sallet and McCaffrey were relatively new agents with six years and four years respectively on the job, but arresting Massino was clearly a career-defining move. It would be all over the news before lunchtime: Joseph Massino, the last of old mob bosses, had finally been taken down. No one was listening to the radio though as the government car traveled westward. Sallet’s music selection droned on instead as he drove.

While sandwiched between McCaffrey and one of the police officers, Massino engaged in some small talk. Conversation about food was what Sallet found best for chitchat with someone being arrested. He asked Massino where he thought the best pizza in town could be found.

“CasaBlanca,” Massino answered. It was his restaurant by Fresh Pond Road in Queens and he knew the sauce was the best in town. Massino was a pretty good sauce man himself. Family dinners at his house would find him holding competitions with his wife over who was the better cook. His daughters were the judges. Massino’s ravioli was often the winner.

It had been inevitable with all the snooping McCaffrey and Sallet had been doing around town that Massino had heard of them.

“You must be Kimberly and you must be Jeffrey,” Massino said to the pair. They politely confirmed this.

Massino also told them he knew they had convinced his wife’s business partner, Barry Weinberg, a chain-smoking Queens businessman who held interests in parking lots all over New York, to wear a recording device. Now Massino, chastened by the Ruggiero tapes, knew that there was no chance that he had been picked up on any recording device Weinberg had been wearing. He never really talked with the man, particularly after some in the Bonanno clan had become suspicious of him. But Massino figured that the only reason he found himself sandwiched between two FBI agents and headed to Manhattan to be booked on an indictment was because somebody close to him had squealed.

“Frankie Coppa got to work quick,” Massino said to the agents as the sedan made its way through traffic.

To the uninformed that terse remark meant nothing. But by blurting it out, Massino was letting Sallet and McCaffrey know that he knew his old friend, Frank Coppa, a Bonanno captain, had become a cooperating witness. Once Massino’s closest of friends, Coppa had been moved from the prison facility at Fort Dix, New Jersey, where he had been serving time for securities fraud, to a federal witness protection prison. It was there that Coppa had been telling investigators what he knew of Massino and the crime family.

Massino now had enough information to know that his predicament was serious. McCaffrey told him that among the many racketeering charges being unsealed that morning in the Brooklyn federal district court were those involving the murders of three rival Bonanno captains in 1981.

“That was a long time ago and I had nothing to do with it,” Massino said.

In fact, Massino had been acquitted of conspiracy to commit those murders in an earlier racketeering trial. The killing of the three captains—Dominick Trinchera, Alphonse Indelicato, and Philip Giaccone—was part of one of New York’s most legendary Mafia power struggles. The remains of the three captains were found in a weedy lot on the Brooklyn-Queens border not far from Massino’s home. Some other crime family members were convicted of the murders in 1983. But in the trial of Massino and his brother-in-law, Salvatore Vitale, the government’s case was weaker and they beat the rap.

In the mob, all friendships could be dangerous. If Coppa or anyone else had been telling investigators what they knew of the deaths of the three captains, they could come back to haunt Massino. McCaffrey thought it curious that right after being told that he was charged with having actually participated in those killings that Massino asked if his brother-in-law had been arrested as well.

Yes, he had been, Massino was told.

Though he didn’t respond or show any emotion when told of Vitale’s arrest, the news must have caused Massino’s already high blood pressure to spike. The brother of Josephine Massino, Vitale had been Massino’s childhood friend and over the years had become a close confidant. Massino shared a lot with him, from learning how to swim in the Astoria pool to introducing Vitale to the illegal scores with truck hijacking. Eventually, as Massino rose in the ranks of the mob, Vitale rode his coattails, rising to the rank of underboss. “Good Looking Sal” or “Sally,” as Vitale was known, relished the aura of being a mob boss. His vanity was a subject of gossip. His favorite cologne seemed picked as if to symbolize his status: it was the “Boss” fragrance of designer Hugo Boss.

Normally, the underboss position is a powerful one in the Mafia, but over the years Vitale had chafed at the paltry power Massino had given him, going as far as to forbid Vitale from speaking to the captains in the crime family. The trust that once ran deep between the two men had evaporated. Some of the Bonanno captains thought Vitale was too dirty and knew too much to be trusted. Better off with Vitale dead, some said. Privately, they wondered if Massino’s judgment about Vitale was clouded by the fact that he was his wife’s brother.

Vitale had been involved in a number of murders—“pieces of work,” as wiseguys would call them. Knowing what he knew about the crime family business, Vitale could be dangerous if he weakened. And Massino knew that. Just three weeks earlier, a few Bonanno mobsters voiced distrust of Vitale.

“Sal is gonna rat on every fucking body,” said Anthony Urso, one of Massino’s key captains, who was overheard on a surveillance bug.

Rats were the bane of the Mafia. La Cosa Nostra was riddled with them and it made Massino even more paranoid. If he suspected any man was a rat, Massino gave him a ticket—he called it a “receipt”—to the grave. Joseph Massino was from the old school of tough guys who never turned on their friends. You never squeal: it was a creed that Massino even taught his daughters to live by. It was the way of life and you swore to it with your blood the day they made you a wiseguy by burning the card with a saint’s picture in the palm of your hand.

Massino would tell people he was proud of his crime family, the only one that had never had an informant or rat in all its years of existence. Omerta had never been violated within the family until old man Joseph Bonanno revealed some of La Cosa Nostra’s secrets in his 1980 autobiography A Man of Honor. Massino had become so angry over Bonanno’s tale that he wanted to change the name of the crime family to Massino. Time in jail, not tell-all books, went with the job of being a mob boss. John Gotti, Vincent Gigante, Carlo Gambino, Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo, Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno, Carmine “the Snake” Persico—they all took their medicine and didn’t rat out anybody. Massino would be a stand-up guy. That was part of a boss’s job. Everybody knew that.

It turned out McCaffrey was wrong in her characterization of the charges against Massino during the car ride back to Manhattan. It might have been a ploy to see if Massino talked, but the indictment in the process of being unsealed that morning by Brooklyn federal prosecutors did not mention the killings of the three captains. In reality, Massino had been indicted for the 1982 slaying of another old friend: Dominick “Sonny Black” Napolitano. The killings of Trinchera, Giaccone, and Indelicato, as well as several others, wouldn’t be laid at Massino’s feet until much later.

The FBI car in which Massino rode went through the Brooklyn-Battery Tunnel, north on West Street, left onto Worth Street, and then headed into the basement of the forty-five-story federal office building known as Twenty-six Federal Plaza. A 1960s-style soaring rectangle of glass, stone, and chrome on Foley Square, the building housed most of the federal law enforcement agencies in the city. Anyone arrested in a major FBI operation—and Massino’s bust was big—was usually taken to “Twenty-six Fed” and put through the ritual processing: fingerprinting, photographing, and the recording of personal information. One thing the agents decided against was a “perp walk,” that is, parading Massino before prying newspaper photographers. They had decided to treat him with a little dignity.

For the Bonanno squad known by the designation C10, the processing of defendants all took place on the twenty-second floor and although it was serious business, Massino couldn’t help joking with the agents as he was fingerprinted, saying he probably wouldn’t get bail if he hired one attorney he knew from the old neighborhood. The agents knew at that point that bail was the remotest long shot for Massino, but they let his remark pass. Spotting one of the squad supervisors, Nora Conely, Massino had a flash of recognition. He remarked that he had seen her talking once to his old friend Louis Restivo, one of the owners of CasaBlanca Restaurant, about a fugitive.

She was second in command of the squad, McCaffrey explained to Massino.

“Like an underboss,” Massino answered McCaffrey, putting it in lingo he understood.

Massino was going to spend the rest of the day shuttling between the FBI offices and across the Brooklyn Bridge to the U.S. District Court, where he would eventually be arraigned on the charges before a federal magistrate. It would take hours for that to happen. In the meantime, as the rest of the city awakened, another ritual was getting underway. Federal officials began to alert news agencies that they had a big announcement and at One Pierrepont Plaza, an office tower in downtown Brooklyn, copies of a four-page press release were stacked on a table in the law library of the office of the U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York, a fancy way to describe Brooklyn and everything to the east.

The document had a long title: Boss and Underboss Charged with Racketeering, Murder, and Other Crimes in Culmination of Four-Year Investigation and Prosecution of the Bonanno Organized Crime Family—Murders Include Retaliation for Infiltration of Family by “Donnie Brasco.”

Press releases from prosecutors don’t just relate the news; they also mention who the big shots are in law enforcement who want credit, or at least hope to get some mention in the news accounts that will follow. This press release was no exception. It listed Roslynn R. Mauskopf, U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of New York; Kevin P. Donovan, Assistant Director in Charge, Federal Bureau of Investigation, the man who was McCaffrey and Sallet’s boss; Paul L. Machalek, special agent in charge of the criminal investigations unit of the Internal Revenue Service; and James W. McMahon, the superintendent of the New York State Police.

The next four names listed in the press release told the world who was in trouble. First named was Massino, “who is the only boss of the five LCN families in New York not currently incarcerated.” In law enforcement jargon the initials LCN stood for La Cosa Nostra, the Italian expression commonly used to describe the American Mafia. Though the public, press, and even police refer to organized crime composed of men of Italian heritage as the Mafia, purists are quick to point out that the term Mafia really refers to the organized crime based in Italy. The term la cosa nostra, which loosely translates as “our thing” or “this thing of ours,” is actually what the FBI prefers.

Rounding out the list of those arrested that morning was, as Massino already knew, Salvatore Vitale, “who serves as the family’s underboss.” Also nabbed was Frank Lino, a mean-spirited, fireplug-sized Brooklyn man seven years’ Massino’s senior who had somehow survived mob infighting to become a capo or captain. Finally, there was Daniel Mongelli, a pubescent-looking thirty-seven-year-old who made up for what he may have lacked in intelligence with loyalty to a life of crime. His reward was the title of acting captain in Massino’s regime.

As she gripped the podium before the assembled reporters and photographers, federal prosecutor Mauskopf said that the arrest of Massino and Vitale meant that the leadership of the Bonanno family was either in prison or facing the prospect of a lifetime behind bars. This was Mauskopf’s first major organized crime indictment and her statement included such usual obligatory prose. She reminded everyone that the government was committed to eradicating the influence of organized crime in the city and that the case demonstrated this resolve.

But she also noted that this was a superseding indictment, meaning it built on an earlier set of charges that had led to the arrest of other Bonanno crime family figures like captains Anthony Graziano, Richard Cantarella, and Massino’s old friend, Frank Lino. In all, Mauskopf noted, twenty-six members and associates of the Bonanno clan had been charged in the previous twelve months. Clearly, the crime family was facing big trouble. Time, she said, had not been good to the mob.

“In the early years, the middle years of the twentieth century, the structure of traditional organized crime was formulated, in large measure right here in Brooklyn,” Mauskopf told the reporters assembled in her office. “At the beginning of the twenty-first century, as a result of federal law enforcement’s efforts, their determined, their sustained, and their outstanding efforts, the heads of the five families and a significant portion of their members had been brought before the bar of justice.”

Such self-congratulatory comments by law enforcement were common at such news events. But Mauskopf’s attempt to give the case a touch of history caught the attention of many journalists who had been following the machinations of organized crime. The reference to “Donnie Brasco” and the murders that surrounded him tied Massino’s arrest to one of the most legendary sagas of latter-day Mafia history. Brasco was in fact Joseph Pistone, who as an FBI agent beginning in the late 1970s infiltrated a branch of the Bonanno family. (Pistone’s role was celebrated in the 1997 film Donnie Brasco starring Al Pacino.) Working undercover, Pistone posed as Brasco, jewel thief. With the patience of a crafty spy, he ingratiated himself with Bonanno soldier Benjamin “Lefty Guns” Ruggierio and his captain, Dominick “Sonny Black” Napolitano.

For three years Pistone gathered evidence against his mob friends, fooling them so completely that he was even proposed for membership to the crime family, a state of affairs that had angered Massino if only because no one really knew this Brasco fellow. In hindsight, Massino’s wariness about Pistone demonstrates his survival instincts. When Pistone’s undercover role was dramatically and publicly revealed in 1981, the results were predictable. Like the dark days of some Stalinist purge, the Bonanno family went through bloody days of reckoning. Those who had allowed Pistone to infiltrate the family had to pay the price. Napolitano was high on the list and federal officials believed he was murdered for the unpardonable sin of vouching for Pistone. The indictment charged that Massino, along with Frank Lino, engineered Napolitano’s slaughter.

Pistone’s infiltration of the Bonanno family had made it not only the laughing stock of the Mafia but also a pariah. Believing they couldn’t trust the Bonanno hierarchy, the other mob families in New York kept the wounded family at bay and cut it out of some rackets. Among the fruits denied the Bonanno family was a cut of the lucrative “concrete club” that had evolved in the early 1980s. The club members were the four Mafia families who took a percentage through kickbacks of every cubic yard of concrete that was poured in New York City. This amounted to millions of dollars in illegal profits and contributed to what critics said was the inordinately high cost of doing construction in New York.

It was in May 1984, in a private home on Cameron Avenue in Staten Island, that the boss of the Gambino family crime family, Paul Castellano, lorded over a meeting of representatives of three other Mafia families—the Genovese, Colombo, and Lucchese families—to hash out business disputes over their construction rackets, including the concrete shakedown. Investigators were also watching and recorded the men going to the meeting. In 1986, federal prosecutors in Manhattan secured convictions for the concrete racket against the leadership of the Mafia Commission: Anthony “Fat Tony” Salerno (Genovese crime family), Anthony “Tony Ducks” Corallo (Lucchese crime family), Carmine “the Snake” Persico (Colombo crime family), and their assorted lieutenants for taking part in various rackets.

But the Bonanno family, having been denied a cut of the concrete scheme, escaped conviction in the Commission case. True, Philip Rastelli, the Bonanno boss at the time, had been indicted. But Rastelli’s case had been severed from the Commission trial and was never convicted. (He was found guilty in an unrelated Brooklyn federal racketeering trial.) Ironically, by being kept out of the loop by the other crime families in the concrete case, the Bonanno clan dodged a big bullet and continued to operate with much of its leadership intact. While other crime families were knocked off balance, the Bonannos were able to consolidate and recover from the disaster of L’Affaire Brasco.

But that honeymoon was over. The news release that accompanied Massino’s indictment listed more murders. Vitale, investigators said, had set up the murder of Robert Perrino, a delivery supervisor at the New York Post, in 1992. After Manhattan District Attorney Robert Morgenthau began an investigation into the Bonanno family’s infiltration of the newspaper’s delivery department that investigators believed had become a mob fiefdom, Vitale panicked. The indictment charged that Vitale and others, fearing Perrino might cooperate with law enforcement, arranged for the newspaper supervisor’s death in 1992.

Daniel Mongelli was charged with killing Louis Tuzzio in 1990. Tuzzio was a crime family associate whose death had already been charged in an earlier indictment against Robert Lino, Frank Lino’s cousin. Tuzzio was murdered as a favor to John Gotti, payback for a bizarre shooting stemming from the death of Everett Hatcher, a Drug Enforcement Administration agent, at the hands of aspiring Bonanno family member Gus Farace in 1989. Tuzzio didn’t die because Hatcher had been killed but rather, investigators said, because one of Gotti’s associates had been wounded during the killing of Farace. Gotti had to be appeased. The mob can police its own as payback for screw ups—Hatcher’s murder brought a lot of law enforcement heat on the mob—but it better be done cleanly.

There were some other charges against Massino involving gambling in cafés in Queens. Joker Poker machines and baccarat games were profitable staples of the crime family along with loan-sharking, which Massino was also charged with. But loan-sharking and gambling charges against a mob boss were an old story. What really had Massino tied up was murder. While more killings would be laid at Massino’s feet in the months to come, prosecutors only needed one—the Napolitano hit—to make the case that Massino should not be given bail.

“It has taken over two decades to get the goods on Joe Massino for the murder of ‘Sonny Black’ Napolitano, but justice delayed is not always justice denied,” said Kevin Donovan, the top FBI boss for New York City, to reporters.

Donovan referred in passing to a pair of agents who had doggedly tracked Massino for years. But he didn’t mention their names. Sallet and McCaffrey didn’t seek adulation and preferred to keep a low profile.

Massino’s youngest daughter, Joanne, had walked her own daughter to the nearby parochial school on the morning of January 9 as she always did. The child had often accompanied both her mother and grandfather on shopping trips to Cross Bay Boulevard in Howard Beach, Queens, near Kennedy International Airport. Joanne had felt the peering eyes of the FBI and, like her father, had spotted the numerous cars that seemed to be following them.

It was a little after 8:00 A.M. when Joanne came back to her home on Eighty-fourth Street in Howard Beach. Both she and her eldest sister, Adeline, had decided to stay close by their parents after each girl got married, so it was almost a daily ritual that the Massino girls saw their parents. (A middle sister had moved out of state.) Now that Joanne was divorced, she remained in the home she once shared with her ex-husband, who had moved to Long Island. As soon as she returned from escorting her daughter to school, Joanne spotted her mother in front of her own home a few doors away. The older woman didn’t say a word, she just gestured.

“Come here, quick, I have something to tell you about your father and it isn’t good,” Josephine Massino seemed to say with an urgent wave of her hand toward her daughter, who knew in an instant that there was trouble.

Adeline, who lived about four blocks north of her parents, was at the Dunkin’ Donuts store on Cross Bay Boulevard, the very same place the FBI agents would visit to pick up snacks for the long surveillances of her father. It was the morning ritual of this particular Howard Beach Little League mom to get her cup of coffee there and then visit her folks.

Though Joanne had the dark Neapolitan eyes of her father, Adeline took after her mother, right down to the auburn tint of the hair (which if truth be told, they both had done at the same beauty salon on the boulevard). Walking with her embossed coffee cup through the front door of her parents’ house, Adeline was oblivious to the tumult that had begun to envelope her family. She would find out about it soon enough.