Читать книгу Sticks & Stones / Steel & Glass - Anthony Poon - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

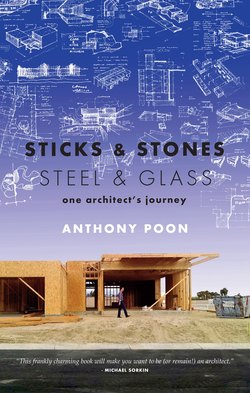

ОглавлениеPrelude

Sunset over Hermosa Beach

I can’t do what ten people tell me to do. So I guess I’ll remain the same.

OTIS REDDING AND STEVE CROPPER

We won the competition—three times. And we lost—three times!

The three-year affair known as the Hermosa Beach Pier design competition of the early nineties was mostly a hard lesson in personal naïveté, civic dithering, and professional backstabbing. The sunny part of it, however, was that it enabled my design partner and me to engage in an aspect of architecture—public space—that is not discussed as passionately as are tangible exhilarating structures of steel and glass.

Public space is architecture that is shared by all who encounter it directly or who live or work nearby, not just by the inhabitants of a home or office. An individual, a group, a community—they all share and flourish in a public space, no matter how small. I’m not talking just about the great parks of the world, the lungs and soul of any city; they are of course essential to people of all means to spend an afternoon surrounded by trees and grass, away from concrete and noise.

I’m obsessed with plazas, vest-pocket parks, and expanded thoroughfares that give us five, ten, thirty minutes of respite. Even passing by a well-designed urban oasis can calm or energize us. To open up, look up, look around . . . before rushing on to the next destination.

For my early architectural studies, I conducted yearlong research into the public square that defined my growing up: San Francisco’s Portsmouth Square. Often called the “Heart of Chinatown,” it shaped how I look at a city and at how people gather within it.

Portsmouth Square was carved out of the dense urban environment of Chinatown’s old buildings. As a child, I climbed its play equipment; as a youth, I met my friends there after hours; as an adult, I celebrated my wedding there. Imagine my wife’s bright white silk wedding dress against the gritty and grainy city backdrop, people on aged benches staring at us with curiosity, and the old men playing chess, not missing a strategic move, undistracted by a wedding party in tuxedos and gowns. Years later, my children would play in the same recreational areas of that venerable public space.

My photographs of Portsmouth Square went on exhibit at UC Berkeley and were later included in a book titled People Places: Design Guidelines for Urban Open Spaces. That vital public park imprinted on me. And it has informed much of my career’s work.

As I backpacked through Europe during college, the piazzas, church squares, and gardens struck me collectively as an elemental form of architecture. I expected it, truth be told, but in the Piazza del Campo in Siena, I witnessed a civic jam session: children playing impromptu sports, groups dancing to live music, raucous political debates, benchlong napping, art students hocking their colorful creations, and one very romantic couple—and then me, the tourist and student in awe of how all this came together.

The final composition of a public space should boom with the splendor of a city performing on stage for the world to witness. As a city-scale work of cultural and social art, a public space and the activities within it are an expression of a community that is alive.

Southern California in 1992. Economic times were tough, but the sun always shone. We were young, Greg Lombardi and I. I was twenty-eight and he thirty.

We formed a partnership, but we didn’t go the artificial acronym route fancied by our colleagues. For us, there would be no OMA (Office for Metropolitan Architecture), FOA (Foreign Office Architects), or the illustrious Office dA (de, as in from Architecture?) in Boston. Our fancy name? Lombardi/Poon Associates.

Years later, when we obtained our state licenses as architects, we became—this is clever—Lombardi/Poon Architects. Rather than spend money on printed and embossed business cards, we ordered a fifteen-dollar custom rubber stamp and hand stamped our company’s name onto precut card stock.

We were both trapped in miserable jobs: I as a paralegal temp and Greg as a corporate monkey at Universal Studios in Hollywood. We met in the evenings and on the weekends to plan and to sketch, just to keep our creative juices flowing.

We decided to enter a design competition organized by The American Institute of Architects for the redesign of the pier and waterfront of Hermosa Beach, one of the Los Angeles beach towns made famous by surf movies and volleyball tournaments: Hermosa, Manhattan, and Redondo Beaches, the cedar-shingled, salty cousins south of Santa Monica and Venice Beach. The trio of towns was and still is a string of funky pearls along the sweet curve of Santa Monica Bay.

Southern California loves its piers, and the piers here last longer than they do on the rest of the Pacific Coast or the East Coast. They aren’t lashed as often by major storms, and a long, sloping shelf receives and holds the concrete pilings. Hermosa’s pier, like the pier in every other beach town, was a place to fish and drink, or just do nothing. Piers are potent symbols of civic pride. We don’t build up so much here; we often build out.

The competition was stiff, with some of the biggest names in Southern California as well as many international entrants in the running. Leading the group of jurors for the competition was teacher, practitioner, and community and industry leader Charles Moore, recipient of the 1991 Gold Medal from The American Institute of Architects. His 1978 Piazza d’Italia in New Orleans had captured worldwide attention and earned him a reputation as one of the original voices of Postmodernism.

The mighty local design studios of Morphosis and Eric Owen Moss Architects were believed to be the frontrunners. Greg and I would be the minnows.

Our design strategy was to consider the waterfront, the plaza at the foot of the pier, and the surrounding beach area as a blank canvas for a broad public space. Our philosophy was that the redesign should be a backdrop for the many activities of visitors to the beach: the bicyclists, the volleyball players, the families looking for recreation, the couples on a romantic stroll down the longest pier on the West Coast. In contrast to our competitors, who proposed hotels, shopping centers, and other large buildings, we ambitiously and simply proposed public space.

A slight tilt in our plaza design created long steps down to the sand, offering access to the beach while forming an amphitheater from which to watch the sun set. We envisioned a sweeping 250-foot elliptical shape carved out of the plaza leading up to the lifeguard tower, which would provide casual seating and organized traffic. We eschewed a focus on the retail shops; instead we added trees, wide sidewalks, benches and chairs. Public amenities.

Open space, taking advantage of the already beautiful surroundings. Public space.

We presented our scheme on four thirty- by forty-inch boards in an unusual manner. Rather than the expected architectural drawings, models, and computer renderings, we made heavily textured collages of colored paper, magazine clippings, and newspaper scraps. Our architects’ statements were printed like fortune-cookie papers, red on white. Our montages were sandwiched between a clear sheet of acrylic on top and a blue piece of acrylic on the back. The blue acrylic glowed like California sky and Pacific Ocean water when light hit it.

We thought it was magical, beautiful. This aesthetic technique was innovative but also risky. Would the jurors appreciate our concept and presentation style, or would they not even understand our unconventional approach?

Our mantra for this project: People and nature have defined the design, not the architects. With this thesis, we submitted our long-shot, upstart entry into a big-time, big-name, international design competition.

We ended up winning, and then losing and winning subsequent rounds of voting and revoting. It’s a saga not for this moment, but I did learn that my architecture road was going to be a long one—a competitive, creative, maddening, and soul-fulfilling one.

I never lost my affection for public space, for architecture that is for everyone, including a little kid on a swing, or a kissing couple, or chess players.