Читать книгу Slash: The Autobiography - Anthony Bozza - Страница 18

6 You Learn to Live Like an Animal

ОглавлениеWe weren’t exactly the type of people who took no for an answer. We were much more likely to give no for an answer. As individuals, each of us was street-smart, self-sufficient, and used to doing things his way only—death before compromise. When we became a unit that quality multiplied by five because we’d have one another’s backs as fiercely as we’d stood up for ourselves. All three of the common definitions of the word gang definitely applied to us: 1) we were a group who associated closely for social reasons such as delinquent behavior; 2) we were a collection of people with compatible tastes and mutual interests who gathered to work together; and 3) we were a group of persons who associated for criminal or other antisocial purposes. We had a gang’s sense of loyalty, too: we only trusted our oldest friends, and found everything we needed to get by in one another.

Our group willpower drove us to succeed on our own terms but never made the ride any easier. We were unlike the other bands of the day; we didn’t take kindly to criticism from anyone—not our peers, not the charlatans that tried to sign us to unfair management contracts, not the A&R reps vying to hand us a deal. We did nothing to court acceptance and we shunned easy success. We waited for our popularity to speak for itself and for the industry to take notice. And when it did, we made them pay.

We rehearsed every day, working up songs that we knew and liked from one another’s bands, like “Move to the City” and “Reckless Life,” which were written by some version or another of Hollywood Rose. We had a piece of shit PA, so we composed most of the music without Axl actually singing with us. He’d sing under his breath and listen and provide feedback on what we were talking about in the arrangements.

After three nights we had a fully realized set that also included “Don’t Cry” and “Shadow of Your Love,” and so we unanimously decided that we were now fit for public consumption. We could have booked a gig locally, because, collectively, we all knew the right people, but no, we decided that after three rehearsals, we were ready for a tour. And not just a long weekend tour of clubs close to L.A.; we took Duff up on his offer to book us a jaunt that stretched from Sacramento all the way up to his hometown of Seattle. It was completely improbable but to us it seemed like the most sensible idea in the world.

We planned to pack the gear and leave in a few days, but our zeal scared the shit out of our drummer, Rob Gardner, so much that he more or less quit the band on the spot. It didn’t surprise anyone because Rob could play well enough but he didn’t fit in from the start; he wasn’t of the same ilk, he wasn’t one of us: he just wasn’t the sell-your-soul-for-rock-and-roll type. It was a polite departure—we couldn’t imagine anyone who had played those last three rehearsals not wanting to tour the coast as an unknown band with nothing but our gear and the clothes on our backs, but we accepted his decision. We would not be stopped, however, so I called the one drummer that I knew who would leave that night if we asked him to: Steven Adler.

We watched as Steven set up both of his silver-blue bass drums and loosened up with a few typical double-bass fills at rehearsal the next day. His aesthetic touchstones were off, but it wasn’t an insurmountable problem. It was a situation rectified in a typically Guns fashion: when Steven ducked out to take a piss, Izzy and Duff hid one of his bass drums, a floor tom, and some small rack toms. Steven returned, sat down, and started counting in the next song before he realized what was missing.

“Hey, where’s my other bass drum?” he asked, looking around as if he’d dropped them on the way to the bathroom or something. “I came here with two …and my other drums?

“Don’t worry about it, man. You don’t need them, just count off the song,” Izzy said.

Steven never got his extra bass drum back and it was the best thing that ever happened to him. Of the five of us, he was the most conventionally contemporary, which, all things considered, lent a key element to our sound—but we weren’t going to let him hammer that point home all night long. We bullied him into being a straight-ahead, 4/4 rock-and-roll drummer, which complemented and easily locked in with Duff ’s bass style, while allowing Izzy and me the freedom to mesh blues-driven rock and roll with the neurotic edge of first-generation punk. Not to mention what Axl’s lyrics and delivery brought to it. Axl had a unique voice; it was brilliant in range and tone, but even though it was often intense and in your face, it had an amazingly soulful, bluesy quality to it because he had a choir background from singing in church when he was in grade school.

By the end of his tryout, Steven was hired and the original Guns N’ Roses lineup was locked and loaded. Duff had booked the tour; all that we needed was wheels. Anyone who knows a musician well, successful or otherwise, knows this: generally, they are adept at “borrowing” from their friends. It took one phone call and very minor convincing for us to enlist our friends Danny and Joe, whose car and loyalty we made use of very regularly. To sweeten the deal, we christened Danny our tour manager and Joe our roadie and the next morning drove Danny’s weathered green tank of an Oldsmobile out to the Valley to pick up a U-Haul trailer that we filled with the amps, guitars, and drum kit.

Seven of us packed into this mid-seventies Olds and set out on what I don’t think anyone but Duff realized was a trip of over a thousand miles. We were outside of Fresno, two hundred miles from L.A. and two hundred short of Sacramento, when the car broke down. Danny wasn’t the type of guy to have splurged for AAA, so luckily we broke down within pushing distance of a gas station, where we discovered that it would take four days to get the necessary parts to fix a beast that old. At that rate, we wouldn’t make any of the shows.

Our enthusiasm was too great to allow for delays or thoughts of practicality, so we told Danny and Joe to stay with the car and gear until it was repaired and to meet us in Portland (about seven hundred fifty miles away), at one of the gigs on the route. From there, we decided we’d drive to Seattle together (about a hundred and seventy-five miles farther) to play the final show of our tour with our own gear. There was a brief moment when Danny and Joe campaigned for us to remain in Fresno together until the car was back on the road, but neither that nor the obvious option of turning back were ever considered seriously. We hadn’t even considered how to get from one gig to the next, let alone that we might not find amps and drums ready to borrow when we got there. We really didn’t give a shit about any of that; the five of us didn’t hesitate—we hit the highway to start hitchhiking.

We gave Danny and Joe whatever money we could spare to pay for the car—probably about twenty bucks—and walked up the on-ramp to the highway, guitar cases in hand. A few hours without so much as one vehicle even slowing down to check us out didn’t dent our confidence. We remained proactive, testing the efficiency of the various hitchhiking configurations available to us: five guys with no visible luggage; two guys hitching and three guys hidden in the bushes; one guy with a guitar case; just Axl and Izzy; just Izzy and me; just Axl and me; just Steven alone, waving and grinning; just Duff alone. Nothing seemed to work; the people of Fresno weren’t having us in any way, shape, or form.

It took about six hours for our kind of misfit to come along; a trucker willing to take all of us on board, stuffed into the front seat and the small bench behind it in his cab. It was close quarters, made even closer by the guitar cases and the sheer intensity of this guy’s speed habit. He shared his stash with us sparingly, which made his endless stories of life on the road more digestible: the five of us were all pretty cynical and sarcastic, so in the beginning we were thoroughly amused by this guy’s insanity. As that night, the next day, and the day after that came screaming down the road at us through the windshield, there wasn’t anyplace else I thought I’d rather be. When we’d pull over at rest stops so this guy could sleep for a while in the back of his cab—which was a consistently inconsistent amount of time lasting anywhere from an hour to half a day—we’d crash on park benches, write songs as the sun came up, or just walk around kicking trash at squirrels.

After a couple of days of this, our chauffeur started to smell particularly pungent and his formerly affable, strung-out chatter seemed to turn darkly weird. We were soon collectively disenchanted. He informed us that he planned to take a detour to pick up more speed from “his old lady,” who I guess drove out to meet him at regular spots on his route to keep him juiced up. It didn’t look like the situation was bound to improve. The next time he pulled into a rest stop to take one of his endless naps, we were way too bored and broke to stick it out any longer. We decided to explore our options by hitting the blacktop to again look for a ride, figuring that if worse came to worst, the speed demon in the semi would find us and pick us up again whenever he woke up. He probably wouldn’t even think we’d ditched him.

Our prospects weren’t plentiful, because, among the five of us, not one of us bore an iota of mainstream appeal, from Duff ’s red-and-black leather trench coat to our black leather jackets, long hair, and a few days of road grime. I have no idea how long we waited, but eventually we hailed a ride from two chicks in a pickup truck with a shell. They drove us to the outskirts of Portland, and once we got within the city limits, all was well—Duff ’s friend Donner from Seattle had sent someone to get us who informed us that Danny and Joe had called ahead: apparently the car was too unreliable to make the trip so they had headed back to L.A. It’s not like we cared; we were forging on, even though we’d missed every single gig along the way. It didn’t matter to us so long as we had a shot at making our final show of the tour—it was scheduled to take place in Seattle, and what was meant to be our last gig became the first Guns N’ Roses show that ever was.

Arriving in Seattle was especially victorious both because we’d actually made it (that last drive came off with no problems), and also because Donner’s house was the closest thing I have ever seen to Animal House. The day we rolled in, they threw a barbecue in our honor that, as far as I could tell, never seemed to end—it was as raging when we dragged ourselves out of there as it had been when everyone first cheered the five strangers from L.A. who came through their door. There was an endless supply of pot, a ton of booze, and people sleeping, tripping, or fucking in every corner. It was a fitting Guns N’ Roses after-show party …that started before our first show.

We arrived at Donner’s house a handful of hours before we were supposed to be onstage. We had nothing but our guitars, so we really needed to find ourselves equipment. As I said, before moving to L.A., Duff had played in legendary Seattle punk bands, so he could pull in some favors: he gave Lulu Gargiulo of the Fastbacks a call, and she came through for us by loaning us their drum kit and amps. She personally made the first Guns N’ Roses show possible. And I’d like to thank her right now once again.

The club was called Gorilla Gardens, which was the epitome of a punk-rock shit hole: it was dank and dirty and smelled of stale beer. It was situated right on the water, on an industrial wharf that lent it a vaguely maritime feel, but not in a picturesque, wooden dock manner at all. That place was at the end of a concrete slab; it was the kind of setting where deals get made in East Coast gangster movies, and on top of all of that, it was cold and raining outside the night we played there.

We just got up and did our set and the crowd was neither hostile nor gracious. We probably played seven or eight songs—“Move to the City,” “Reckless Life,” “Heartbreak Hotel,” “Shadow of Your Love,” and “Anything Goes” among them—and it went by pretty quickly. That night we were a raw interpretation of what the band was; once the nervous energy subsided, at least for me, we’d reached the end of the set. That said, we had a very small number of train wrecks in the arrangements, and all in all the gig was pretty good …until we had to collect our money. Then it became as much of an uphill battle as the rest of our early career would be.

The club owner refused to pay us the $150 we were promised. We tackled this obstacle as we had the entire road trip—as a group. We broke down our gear, got it packed up outside of the club, and cornered this guy in his office. Duff talked to him while we crowded around, looking formidable and throwing in a couple threats for good measure. We blocked the door and held him hostage until he finally coughed up $100 of our cash. He had some sort of bullshit excuse about why he was shorting us $50 that was just fucking dumb. We didn’t care to get to the bottom of it at all, so we took the $100 and split.

THERE IS ONE IMAGE THAT I HAVE OF our days in Seattle that sums it all up to me. It is of an upside down TV. I remember lying with my body half on the bed, my head hung over the end of the pull-out couch so far that the top of it was against the floor. There were equally rotted people that I didn’t know lying on both sides of me and I was so stoned that I thought I’d found the best position in the world that a body might ever be in. The blood rushed to my brain as I dangled there watching The Abominable Dr. Phibes, starring Vincent Price, and there wasn’t anything else I wanted to do.

After a couple of days of after-partying at Donner’s house, we hopped back in the car with his friend, whom we’ll call Jane. She was either crazy or just liked us enough to drive us all the way back to L.A.. I’m still not sure which. We drove through to Sacramento, which is about seven hundred fifty miles, before we made our first pit stop. By that point, we had to pause: Jane wasn’t the type to have a car with functioning air-conditioning, and considering the summertime heat, it might have been lethal to keep going by that point.

We parked and spent the afternoon wandering around the state-capitol area begging for change to get something to eat. After a few hours, we took our earnings and hit the McDonald’s and we barely had enough food to share among the six of us. Afterward, we lay down under the shade of a few oak trees in the park across from the capitol in search of some relief from the heat. It got so unbearable that we jumped the fence and took refuge in some convalescent home’s pool. We didn’t give a fuck that we were trespassing; actually, if we’d gotten arrested, it probably would have been an improvement—at least there would be food and better air-conditioning than Jane’s car. Once the sun went down and it finally cooled off enough to get back in that thing, we got back on the road.

I didn’t realize it until years later, but that trip cemented us as a band more than we knew; our commitments were tested on that journey. We’d partied, we’d played, we’d survived, we’d endured, and we racked up a lifetime’s worth of stories in just two weeks. Or was it one week …I think it was one week …what do I know?

IT MAKES SENSE THAT GUNS’ FIRST SHOW took place in Seattle because as much as L.A. was our address, we had as much in common with the average “L.A.” band as Seattle’s weather has with Southern California’s. Our main influences were Aerosmith, especially for me, and then there was T. Rex, Hanoi Rocks, and the New York Dolls. I guess you could even say that Axl was a version of Michael Monroe.

So we were back in L.A. with our first-ever gig as a band behind us. We were all set to get back to rehearsing and keep the momentum focused. We got together out at this space in Silverlake and were all packed into Duff ’s little Toyota Celica driving home after rehearsal. As we pulled into an intersection to make a left turn, we were broadsided by some guy doing about sixty miles an hour. Steven broke his ankle because his legs were stretched out between the two front seats, and everyone got pretty banged up, myself least of all—I walked away unscathed. It was a pretty gnarly little accident; Duff ’s car was totaled and we could have been, too. That would have been a sick twist of fate: the band dying together after we’d just gotten together.

WE STARTED HANGING AROUND WITH A few of the seedier rock-and-roll people in the L.A. scene; they were part of an underbelly that the typical Sunset Strip rock fan didn’t know about. One of the characters was Nicky Beat, who was the drummer for L.A. Guns for a minute, but mostly spent his time playing in lesser-known glam bands like the Joneses. Nicky wasn’t necessarily seedy but he had a lot of seedy friends. He also had a rehearsal studio in his house in Silverlake where we’d go, set up our gear, and jam, and that is where the whole band really came together. Izzy had something called “Think About You” that we liked, and we revisited “Don’t Cry,” which was the first song I’d ever worked on with Izzy. Izzy had another riff for a song called “Out Ta Get Me” that clicked with me immediately when I first heard it—we had that one done in no time. Axl remembered a riff that I’d played him when he was living over at my mom’s house, which was ages ago at this point: it was the introduction and the main riff to “Welcome to the Jungle.” That song, if anything, was the first real tune that the band wrote together. We were sitting around rehearsal looking to write something new when that riff came to Axl’s mind.

“Hey, what about that riff you played me a while ago?” he asked.

“When you were staying with me?” I asked.

“Yeah. It was good. Let’s hear it.”

I started playing it and instantly Steve came up with a beat, Duff joined in with a bass line, and away we went. I kept throwing parts out to build on it: the chorus part, the solo, as Axl came up with the lyrics.

Duff was the glue on that song—he came up with the breakdown, that wild rumbling bass line, and Izzy provided the texture. In about three hours, the song was complete. The arrangement is virtually the same as it appears on the album.

We needed an intro and I came up with one that day using the digital delay on my cheap Boss guitar pedal board. I got my money’s worth out of that thing, because as crappy as it was, that pedal provided the tense echo effect that set the mood for that song and eventually the kickoff for our debut album.

A lot of our earliest songs came to us almost too easy. “Out Ta Get Me” came to be in an afternoon, even faster than “Jungle.” Izzy showed up with the riff and the basic idea for the song and the second he played it, the notes hit my ear and inspired me. That one happened so quickly, I think that even the most complicated section—the dual guitar parts—were written in under twenty minutes.

I had never been in a band where pieces of music that I found so inspiring came so fluidly. I can’t speak for the other guys, but judging by the speed at which our collective creativity came together I assume they felt something similar. We seemed to share this common knowledge and a kind of secret language back then; it was as if we all already knew what the other guy was going to bring into rehearsal and had already written the perfect part to move the song along. When we were all on the same page, it really was that easy.

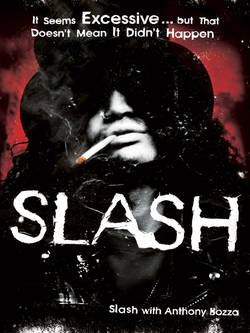

Slash, during Guns’ short-lived glam phase.

WE BORROWED SHIT FROM CHICKS AND initially we had that trashy glam look, though a lot more rough-edged. Very quickly, though, we got too lazy to do the makeup and all that so our glam phase was short-lived. Plus the clothes were a problem because we were always changing girlfriends, and you never knew what the next “she” was going to have. Besides, I don’t think that look ever really suited me—I didn’t have the emaciated white-boy long-haired physique. Ditching the whole idea worked to our advantage in the end: we were grittier, more traditional, and more genuine; more a product of Hollywood itself than the L.A. glam scene.

We were also the lunatic-fringe rock-and-roll band. We thrived on being out of place and took every gig we were offered. We practiced every day, and new songs came quickly; we’d test them in front of bawdy crowds at venues like Madame Wong’s West, the Troubadour, and the Whisky. I looked at whatever we did each day as the next step along a path to where everything was possible. In my mind it was simple: if we focused on nothing but surmounting the nearest obstacle, we’d make our way from Point A to Point C in no time no matter how great the distance.

With every show that we played, we made more fans—and usually a few new enemies. It didn’t matter; as we drew bigger crowds, it was easier to get gigs. Our fans, from the start, were always a mixed bag: we had punks, we had metalheads, we had stoners, we had psychos, the odd weirdo, and a few lost souls. They were never an easily identified or quantifiable commodity …in fact, after all of these years, I am still at a loss for a simple phrase that puts a bow on them—which is fine by me. Guns’ die-hard fans were, I suppose, kindred spirits; misfits who’d made their outcast status their stance.

Once our profile started to grow on the local level, we hooked up with Vicky Hamilton, a manager who’d helped both Mötley Crüe and Poison in their early days. Vicky was a five-foot nine-inch overweight platinum blonde with a whiny voice who just believed in us and proved it by promoting us for free. I liked Vicky a lot—she was very sincere and meant well; she helped me get posters for our shows printed, took out ads in the L.A. Weekly, and dealt with the promoters at our gigs. I worked alongside her doing everything I could to further our cause; with her help, everything began to really take off.

We started playing at least once a week, and as our exposure increased, so did the need to get some new clothes—my three T-shirts, my loaner leather jacket, one pair of jeans, and one pair of leather pants weren’t gonna cut it. I decided that I had to do something about it the afternoon before we played our first Saturday-night headlining slot at the Whisky.

I didn’t have the financial means to make much happen, so I wandered the shops in Hollywood looking for odds and ends. I stole a concho belt from a place called Leathers and Treasures that was black and silver, just like the one Jim Morrison always wore. I planned on wearing it with my jeans or my pair of leather pants (which I’d found in the Dumpster of my grandmother’s old apartment complex) and continued browsing the various shops. I found something interesting in a place called Retail Slut. There was no way that I could afford it, and for the first time in my life, I wasn’t sure how I could steal it—but I knew I had to have it.

A large black top hat doesn’t easily fit under your shirt, though I’ve had so many stolen from me over the years that someone has worked out an effective technique that I don’t know about. In any case, I’m still not sure if the staff noticed and, if they did, whether or not they cared as I blatantly snatched that top hat off the mannequin and casually walked out of the store and never looked back. I don’t know what it was; the hat just spoke to me.

Once I got back to the apartment I was living in at the time, I realized my new “purchases” would best serve each other by becoming one: I cut the belt to fit the top hat and was happy with the way it looked. I was even happier to discover that with my new accessory pulled down as far as it could go, I could see everything but no one could really see me. Some might say that a guitarist hides behind his instrument anyway, but my hat added an impenetrable comfort. And while I never thought it was original, it was mine—a trademark that became an indelible part of my image.

WHEN GUNS FIRST GOT GOING I WAS working at a newsstand on Fairfax and Melrose. I lived with my on-again, off-again girlfriend Yvonne full-time until she got sick of me, at which point we broke up once more, leaving me nowhere to live. My former manager at the newsstand, Alison, let me crash in her living room and pay her half of the rent. She was a very handsome reggae chick with an apartment on Fairfax and Olympic who was taking college classes at night. Alison was attractive, but I always thought that either she was a little old for me or that I was a little young for her; either way, we never had that kind of relationship. We got along very well, and when she left the newsstand for a better job, I was lucky enough to inherit her position.

Alison always treated me like the cute stray she’d taken in, and I did little to prove her wrong. As her tenant, I didn’t take up much space. My worldly possessions were my guitar, a black trunk full of rock magazines, cassettes, an alarm clock, some pictures, and whatever clothes I owned or had been given by friends and girlfriends. And there was my snake, Clyde, in his cage.

Anyway, the newsstand job came to an abrupt end in the summer of ’85 when a local rock station, KNEC, threw a party out in Griffith Park, complete with free charter buses that departed from the Hyatt on the Sunset Strip. I headed over there after work with two pints of Jack Daniel’s in my jeans, not giving a shit that I was expected to open the newsstand up at five the next morning. It was a pretty debauched summer night as I recall; people passed bottles and joints as the bus made its way across town. There were plenty of local characters and musicians on board, and when we got there, music playing and a barbecue. The grass was full of people engaged in everything.

I got so fucked up that night that I brought a girl back to Alison’s place and was fucking her on the living-room floor when Alison came home and caught us. She didn’t need to say anything—her expression told me that she wasn’t too pleased. I stayed up with this girl anyway until it was time for me to go to work. By the time I got her dressed and on her way, I was already late and my boss, Jake, had called. I was in the doghouse already because I used the phone at the newsstand to conduct band business so often that he’d started calling during my shifts to catch me in the act, which proved to be difficult. Those were the days before call waiting and I was on the phone constantly so it took Jake hours to get through just to yell at me. Needless to say he was pretty pissed off about opening up for me that day.

“Yeah, Jake, I’m sorry,” I mumbled, still pretty drunk when he called for the second time. “I know I’m late, I got held up. But I’m on my way.”

“Oh, you’re on your way?” he asked.

“Yeah, Jake, I’ll be there really soon.”

“No you won’t,” he said. “Don’t bother. Not today. Not tomorrow. Not ever.”

I paused for a minute and let that sink in. “You know, Jake, that’s probably a good idea.”

AT THAT TIME DUFF AND IZZY STILL lived across the street from each other on Orange Avenue. Duff had a working-class-musician mentality like mine—until the band really got going, he didn’t feel right if he didn’t have a job, even if his job was morally suspect. He did phone sales or phone theft, depending on your point of view: Duff worked as a telemarketer for one of those firms that promise people a prize of some kind if they agree to pay a small fee “in order to redeem it.” I had a similar job before I got my job in the clock factory: I’d call people all day, promising them a Jacuzzi or a tropical vacation if they’d just “confirm” their credit-card number to cover their “eligibility fee.” It was a nasty, cutthroat gig and I got out the day before it was raided by the police.

Axl and Steven would do anything not to work a regular job, so they got by on the street, or via their girlfriends’ handouts. Though, as I recall, on occasion Axl and I took jobs together as extras on movie sets. We were in a few crowd shots at the L.A. Sports Arena for a Michael Keaton movie called Touch and Go where he played a hockey player. We didn’t care as much for the camera time as we did getting fed and making money for doing nothing: we’d show up in the morning, get our meal ticket, then find somewhere to sleep behind the bleachers where we wouldn’t be found. We’d wake up when they called for lunch to eat with the rest of the crowd, then sleep until it was time to clock out and collect our hundred-dollar check.

I liked being the industry’s least industrious extra as often as possible: I found absolutely nothing wrong with free lunch and an afternoon of being paid to sleep. I looked forward to the same when I was scouted by a casting director for the film Sid and Nancy. Unbeknownst to any of us, the same casting director in various locales, scouted every single member of Guns N’ Roses individually. All of us showed up to the first day of casting, like, “Hey …what are you doing here?”

It wasn’t much fun; actually, it was like jury duty: there was a pen full of extras, but all five of us were chosen to be in the same concert scene, where “the Sex Pistols” are playing some small club. The shoot required showing up early in the morning, for three consecutive days, with the usual promise of a meal ticket and a hundred bucks each day. A three-day commitment was too much for the other guys. In the end, I was the only one of us pathetic enough to show up for the duration.

Fuck them, I had a blast; for three days, they shot these “Sex Pistols” concert scenes at the Starwood, a club that I knew inside and out. I’d show up in the morning, clock in and get my meal ticket, then disappear into the bowels of the Starwood and get drunk on Jim Beam all by myself. While the other extras were doing their part playing audience members down on the floor in front of the stage, I watched the proceedings from a hidden corner of the mezzanine—and got paid the same wage.

AS GUNS BECAME A CLUB BAND TO BE reckoned with, a few ridiculous L.A. managers started to circle us like sharks, claiming that they had what it took to make us stars. At this point we had amicably and temporarily parted ways with Vicky Hamilton, so we were open to offers, but most of those that we got were just retarded. One of the more convincing examples of how low those types will go and what would be in store for us should we make that mistake came courtesy of Kim Fowley, the infamous character who managed the Runaways the way Phil Spector managed the Ronettes; basically just a legalized form of indentured servitude. Kim gave us his best lines, but the moment he talked about taking a percentage of our publishing and making a long-term creative commitment to him, it was clear what he had in mind. His bullshit and demeanor spoke for themselves because Kim was too odd of a guy to fake it.

I liked him nonetheless and was happy to hang out and be entertained by him—as long as he didn’t get too close. The rest of us were the same kind of animal: willing to take advantage of everything someone might have to offer without making any promises we’d have to keep. Axl would hang out as long as the conversation was worthwhile because Axl is a good talker. Steven was there if there were chicks involved. And I was willing to consume all of the free Denny’s meals, cigarettes, drinks, and drugs in exchange for the conversation I had to put up with. Once the factors that had drawn us in were exhausted, one by one, we’d make our exit.

Kim introduced us to a guy named Dave Liebert, who was Alice Cooper’s tour manager for a time and had worked with Parliament-Funkadelic, only God knows when, and those two were intent on signing us as a team, and taking us for all we were worth. Kim took me over to Dave’s house to meet him one night and I remember Dave showing us his gold records. His attitude was “Hey, kid, this could be you.” I assume he intended to entice me further by inviting two girls over, who were young enough to be his daughters, that spent the night shooting speed in the bathroom. Dave dragged me in there at one point and it seemed like these chicks had no idea what they were doing. They were so inept that I wanted to grab the needle and inject them myself. Dave was into it and, in the unbearable fluorescent light of that bathroom, stripped down to his underwear and fooled around with these girls—who were nineteen at best—and invited me to join in. I remember thinking that of all the reasons why this scene was so very scummy, the lighting was worst of all. The thought of this guy managing our band and Kim Fowley with his collection of prehistoric gold records made it nearly impossible not to just laugh hysterically right in his face. It would have been professional suicide before we ever had something to lose. We’d never stand a chance if the management was as debaucherous as the band, anyway.

AS GUNS KEPT REHEARSING, WRITING, and gigging, working to define who we were, I started going out more. Suddenly there were actually bands I wanted to see because finally the scene was changing: there were bands like Red Kross who were a glam band, but were gritty, and at the other end of the spectrum, there were bands like Jane’s Addiction who were great and that I related to but I wasn’t on the same page with. We played shows with some of those more obscure, arty bands—I remember a gig at the Stardust Ballroom—but they never quite came off right. We weren’t considered hip by the bands in that scene, because they thought of us as a glam outfit from the Troubadour side of town more than we ever really were. What those bands didn’t know is that we were probably darker and more sinister than they were. Nor did they realize that we could not fucking stand our peers on the other side of town.