Читать книгу Cameron at 10: From Election to Brexit - Anthony Seldon - Страница 10

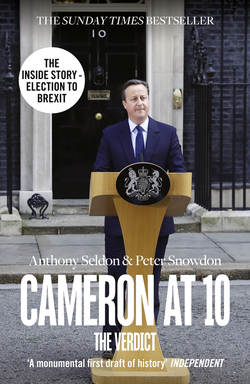

Cameron at 10: 2010–16 The Verdict

ОглавлениеThe decision to hold a referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union was the biggest gamble of David Cameron’s political career. Had the result tipped in his favour, he would have been able to capitalize on his second term, in which he was already developing a distinctive domestic agenda. But like Margaret Thatcher and John Major before him, Britain’s troubled relationship with Europe would leave his premiership in ruins. His downfall was on an even greater scale than theirs. He will forever be remembered as the prime minister who precipitated the country’s most momentous decision in over fifty years, with far-reaching and profound consequences.

How did this happen? None of Cameron’s predecessors had managed to hold the Conservative Party together over the issue of Europe since Britain joined the European Economic Community in 1973. On becoming leader he urged the party to ‘stop banging on’ about Europe, desperate to cast aside years of internecine conflict between Tory Europhiles and Eurosceptics. He came to office in May 2010 with little coherent plan for how to achieve this, beyond hoping that Europe must not overshadow his premiership. Yet within eighteen months, the pressure to commit to a referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union was becoming overwhelming. By the summer of 2012, over one hundred Conservative MPs had added their names to a letter calling on Cameron to make a commitment, fearful that the rise of the United Kingdom Independence Party (UKIP) would destroy the party’s chances of winning the next election. He chose to assuage their concerns by promising a ‘new settlement’ with the EU following a renegotiation of Britain’s membership. The referendum pledge Cameron made in his Bloomberg speech in January 2013 ultimately led to his undoing. It gave the impression of a prime minister reacting to events rather than mastering them.

Cameron’s decision to forge a new deal on Europe and defy the doomsayers in his party has been dismissed by many as foolhardy political expediency. The Bloomberg speech, it is alleged, was an exercise in party management to neutralise the issue until after the 2015 general election. It certainly appeased a growing number of Brexiteers on the front and back benches. But this view dismisses Cameron’s genuine desire to tackle the recurring sore of Europe and his belief that the country would have to address the issue sooner rather than later. It is hard to argue that he had ducked the problem. His error, which would prove fatal, came in the belief that he could secure more than he could from Britain’s European partners, telling the Conservative Party conference in 2014 that he would make progress on free movement and would not take ‘no’ for an answer. Angela Merkel, he hoped, would help him to persuade other European leaders to give Britain stronger safeguards against the swelling influx of migrants attracted by Britain’s strong economy.

Cameron pressed European leaders to cut him a deal in February 2016, believing, with George Osborne, that protracting it would only handicap their cause. The circumstances could not have been less propitious. The EU was in no mood to give Britain anything more, given the migration crisis on Europe’s borders and continuing uncertainty over the eurozone. The package of measures to restrict welfare benefits, provide financial safeguards and a commitment to protect Britain from ‘ever closer union’ did not meet the public’s expectations that Cameron and his team had raised. ‘He was very defensive because he knew it was so hard to get, but most of us knew that even in his own head he was over-claiming,’ admits one. It was not enough to convince Boris Johnson or close ally and friend Michael Gove, whose decisions to join the Leave campaign would cost Cameron dearly.

By leading the charge for the Remain campaign rather than replicating Harold Wilson’s more removed role during the 1975 referendum – a lead Cameron was adamant he should take – he raised the stakes even further. ‘He could have played no further role in the campaign by playing the role of elder statesman,’ argues Graham Brady, chairman of the backbench 1922 Committee. ‘But he was determined to front the campaign and that immediately eroded his credibility.’ But not to have led from the front would have been a failure of leadership. He chose, however, to become highly partisan rather than maintain a more dignified distance, which lost him some dignity and authority. He thus exposed himself to accusations by his own ministers of lying and broken promises about key claims, including reducing immigration to the tens of thousands, and he did not stop direct and personal attacks on senior figures on the Leave side, principally Boris Johnson. When Cameron labelled Leave supporters as ‘Little Englanders’ and ‘quitters’, he managed to offend many grass-roots Conservatives across the country. When the Leave campaign relentlessly pushed the question of immigration, Cameron’s and Osborne’s warnings on the economic risks of leaving the EU lost their potency.

The failure of the Remain campaign and the reality of defeat will loom large in the nation’s mind for many years to come. But what are we to make of his record in office beyond the European question? We should not judge prime ministers as if they all served on a level playing field. Some come to power blessed with advantages, none more so in recent years than Tony Blair, who in 1997 inherited a strong economy, enjoyed a large majority and led a unified Labour Party. Cameron’s inheritance in May 2010 was one of the most challenging for fifty years, worse than the situation Wilson faced in 1974 or arguably even Thatcher in 1979. Yes, he had the good fortune to face Ed Miliband, then Jeremy Corbyn as Labour leader – Miliband’s brother and leadership contender in 2010, David, would have posed a greater challenge – and to have no serious rivals around the Cabinet table to spark a leadership election. Johnson, the one figure with more popular appeal to Tory voters, was ruled out by not being in Parliament until 2015. Where Blair had, in Gordon Brown, a chancellor who undermined him, significantly damaging his effectiveness as premier, Cameron had a chancellor who enhanced his own authority and effectiveness during the coalition. Cameron was fortunate too to have William Hague affirming his leadership, especially earlier in his premiership, with all the authority and experience a former party leader carries. His decision to form a coalition with the Liberal Democrats usefully shielded him from unpopular decisions, particularly over public spending cuts. By entering the coalition, the Liberal Democrats believed they were taking a brave decision – albeit one that would cost them dear at the polls.

But there the blessings end. Cameron’s difficulty in managing his party between 2010 and 2015 was exacerbated by his failure to win an overall majority in May 2010. He came to power at a time of the worst economic crisis since the 1930s. His response was to say that the coalition was ‘governing in the national interest’ – a phrase which imbued his speeches and statements for most of his first twelve months in power. The constraints of the economy and coalition politics were never far from the surface. Like Konrad Adenauer, chancellor of West Germany (1949–63), Cameron displayed uncanny instincts for holding his party and coalition together, but did not win over hearts and minds.

Cameron came to power at a time of widespread anti-establishment feeling and disillusion across the nation. It ultimately contributed to his undoing by way of the EU referendum defeat, and contributed to British politics being in an unusually febrile and volatile state after 2010. The stellar rise of UKIP in 2013–14 threatened the most dangerous split on the right for generations. Cameron had the Conservative press on his back, particularly from 2011–13, partly in anger at his setting up the Leveson Inquiry. As with John Major, but unlike with Margaret Thatcher, he had few cheerleaders among the right-wing commentariat or Tory grandees. Most were unwilling or unable to give him credit for his strengths and achievements, or to credit his difficulties. The Fixed-Term Parliaments Act 2011, designed to bind the coalition together, denied him the opportunity to threaten an election at a moment of his choosing, depriving him of a critical tool in disciplining his party. He faced a turbulent House of Lords, an assertive judiciary, rampant Scottish nationalism, and EU laws that, despite his repeated efforts, constrained his ability to limit EU immigration.

Such difficulties explain some if not all of Cameron’s problems. His unforced error in presiding over a confused message in the 2010 general election proved to be crucial. The direction of the Conservative campaign was split, and the prospectus divided between the optimistic if inchoate ‘Big Society’ and the overdone pessimism of austerity on the economy. The election could have been won outright against a discredited prime minister and Labour Party, and a country disillusioned with thirteen years of Labour rule. Cameron was thus to a significant extent the author of some of his own problems during these five years. He was determined not to preside over the same divided campaign in the 2015 election. Vindication followed with the party achieving an overall majority, its first in twenty-three years. Cameron’s victory confounded the predictions of opinion pollsters and many commentators from both sides of the political spectrum. Critics said he only won because of last-minute fears of an SNP–Labour alliance, but research suggests economic arguments and Cameron’s qualities over Miliband were decisive. Victory shattered Miliband’s Labour Party as well as Nick Clegg’s Liberal Democrats. Both parties lost their leaders after the general election and immediately descended into disarray. The Conservatives, despite their slender majority, gained a political hegemony and confidence in the months that followed which they had not known since before Black Wednesday in 1992. It was to be short-lived.

Cameron’s critics have often pointed to his deficiencies as a long-term, strategic thinker. This criticism should not be overplayed or judged devoid of context. If Cameron lacked principles, how do we explain his standing by Plan A on the economy, gay marriage and the decision to spend 0.7% of GNP on international development? He expended considerable political capital in remaining fixed on each of these policies. His years in power were characterised by an uneasy mix of dogged adherence to such policies while displaying marked flexibility on others. He stuck by what he deemed the most important factors: coalition survival and economic recovery. Circumstances openly militated against long-termism, and flexibility is a virtue as well as a vice; often for Cameron it was additionally a necessity.

The economic recovery of 2010–15 defined the character of the coalition and Cameron’s premiership. Economists will argue whether the deficit should have been cut more quickly, or slowly, and whether it was the global economy rather than government policy which was more responsible for the restoration of economic fortunes. Osborne’s failure to eliminate the structural deficit during the life of the parliament, a commitment abandoned after only two years, brought much criticism at the time, though government spending as a proportion of GDP fell from some 45% to 40%, a not insignificant reduction in such a short period. In only five years in power, Cameron and Osborne achieved a reduction in public spending as a proportion of GDP approximately equal to the reduction achieved by Thatcher during the whole of her eleven years in power. By 2014 Britain had the fastest growth rate in the G7, with a strong record on job creation, and falling unemployment (2.2 million more were in work than in 2010), helped by low inflation and low interest rates.

Cameron and Osborne stuck by Plan A, albeit with modification, in the face of severe pressure, particularly during 2011–13. Public spending cuts were painfully felt, particularly by the young, who saw their benefits decline while pensioners were protected. Recovery was hampered by the continuing eurozone crisis and slowdown in global economic growth, but was helped by the fall in oil prices. Productivity remained sluggish by international standards, and real wages struggled to recover to pre-recession levels. The rise in living standards was skewed towards the south-east, which only began to be addressed by Osborne in his Northern Powerhouse strategy from mid-2014. Like Thatcher, Cameron invested great energy for a prime minister in his role as ‘chief salesman’ for the UK abroad, galvanising British companies to export, though export growth remained disappointing. He and Osborne worked hard to inject a more entrepreneurial spirit into British industry, symbolised by Tech-City in East London.

Osborne’s contribution to this government and Cameron’s premiership was seminal. Like Cameron, he grew in stature over the years, recovering strongly from his personal errors of judgement early on, notably the failure to win the 2010 general election outright, and the ‘omnishambles’ Budget of 2012. He was responsible for much of the strategic and tactical thinking of the government, though Cameron overruled Osborne when he thought he was being too tactical or his judgement was wrong. The most instinctive political operator in Cameron’s team, Osborne also possessed the quickest and subtlest mind. Cameron was always the more senior, as when he prevented Osborne from reducing the top rate of income tax to 40% in the 2012 Budget, deterring him from laying into the Lib Dems and gaining tactical advantage but at the expense of long-term strategy. He gave him cover and succour when deeply wounded for much of 2012. They spoke to each other almost every morning and evening over the five years, enjoying the most successful and harmonious senior political relationship of the last one hundred years. The secret of the success was the way they complemented each other: to an uncanny degree they thought as one. The chancellor/PM relationship, when it goes wrong, does so for two reasons: significant differences over policy, and ambition by the junior to replace the senior. In this case neither applied. Osborne knew when to bite his tongue and defer to Cameron, and, uniquely in modern British politics, neither the PM’s nor the chancellor’s teams ever briefed against the other. There were differences of emphasis, certainly: Osborne would have preferred to have been more aggressively liberal on social issues, more of a neocon on foreign policy, tougher on colleagues and backbenchers, and more of a tax and economic reformer, though it was the economic situation rather than Cameron that was the principal restraint. Cameron, the older figure by five years, was always more of a shire Tory, while Osborne was more of an urban liberal.

School reform took prominence among domestic achievements, the work of one minister above all: Michael Gove. He ferociously drove through a series of controversial reforms to make exams more rigorous, to improve the quality of teaching and to give schools more autonomy, establishing an altogether new breed of ‘free schools’, while greatly accelerating Labour’s programme of academies. When Gove was moved in July 2014, his successor Nicky Morgan was given clear instructions to continue his crusade, albeit with a more conciliatory hue. The success of the education reform agenda is far from established, however, with many academies struggling to meet expectations set for them, while the mark on social mobility will not be seen for many years.

Welfare was another domestic achievement, with Iain Duncan Smith introducing significant if contentious reforms to the benefits system to ensure that welfare was targeted at the most deserving, and those out of work were encouraged back into employment. He stuck doggedly to his flagship policy, Universal Credit, designed to unify and simplify previous systems, and against the odds, remained in office throughout the parliament and into the next before his sudden resignation in March 2016. As with education, it is too early to tell whether the ambitious welfare changes will prove an enduring success. Health policy was more uneven still, with two very different phases: a difficult two years when Andrew Lansley tried to introduce some important if flawed reforms to the NHS, and a second when Jeremy Hunt drove through amended reforms and pacified the NHS so successfully that it was not the predominant issue at the 2015 election, despite Labour making it their priority. Health reforms remained highly controversial after 2015, the subject of avid continuing debate.

At the Home Office, the most fraught department of state, Theresa May ran a tighter ship than many of her predecessors, battled to control non-EU immigration, and oversaw a reduction in crime despite severe cuts in the Home Office budget. Domestic successes came in several other areas, including public sector reform, but not in others, with plans for elected mayors in major British cities being largely rejected in local referenda. The record on new housing, the environment and reducing poverty, even with Lib Dem interventions, remained weak. In his second term, Cameron determined to craft a radical policy agenda that would place him as a great social reforming prime minister. It was not to be.

Northern Ireland enjoyed its most peaceful five-year period since the 1960s, due in part to Cameron’s June 2010 acknowledgement of the culpability of the British army on Bloody Sunday in 1972. In mainland Britain, despite cuts, austerity and high unemployment, civil unrest and trade union disruption were largely avoided, with the notable exceptions of the protests over student tuition fees in November and December 2010, and the riots in London and other cities in the summer of 2011. Fusilier Lee Rigby in May 2013 was the only British citizen to be murdered due to Islamist terrorism on British soil during Cameron’s years, despite a considerable rise in threat levels. Several plots, including some of 7/7 proportions, were foiled, through the skill of the intelligence services and police, together with a degree of good fortune. The successful London Olympics proceeded without incident in the summer of 2012. Cameron spoke out regularly about combating terrorism, and would have wanted to go further to fight the threat both in the UK and abroad. But throughout 2010–16, his close personal alertness to the threat of terrorism on the streets of Britain, and his determination to reduce the risk, was clear.

Cameron’s record as a leader abroad, however, is more mixed. He seized the initiative on insisting that British troops withdraw from Afghanistan by the end of 2014, and worked hard to try to ensure that the handover to the Afghans was smooth. Credit is due for the timely and orderly way he brought Britain’s involvement in this long-running war to an end. Another lesson he learnt from Blair’s government was to avoid any hint of the ‘sofa government’ that marked the Iraq War in 2003. He thus set up the National Security Council soon after the general election in 2010, which met weekly and which he himself chaired. The organisation’s first great test came over British intervention in Libya. This was driven by Cameron personally, backed by all members of the NSC and by the Cabinet, and additionally supported by a United Nations resolution. The conclusion of the war and the downfall of Gaddafi in the autumn of 2011 brought Cameron short-term acclaim. He hoped along with many others in the heady initial days of the Arab Spring for a new dawn of democracy across the Arab world. This optimism faltered during the following years as Libya descended into violence and tribal infighting, and Syria was torn apart by civil war. His attempt to involve Britain militarily against Syria’s President Assad in August 2013, after Assad used chemical weapons against his own people, produced Cameron’s biggest first-term foreign policy reversal, when he was defeated in the House of Commons. This defeat, and the deteriorating position in Libya, made him less inclined to assert his will in the final year and a half leading up to the general election in 2015. Humanitarian instincts drove him to intervene in Libya in 2011, and to try to intervene in Syria in 2013. He was not the first British leader whose aspirations in the region were to be thwarted by forces far more powerful than anything they could control. He can be criticised certainly for acting; equally, inaction would have resulted in opprobrium, and other risks. His foreign policy was marked by a strong ethical underpinning.

The recovery of the British economy and Cameron’s strong relationship with President Obama were significant in countering the widespread narrative about a loss of British influence on the world stage. Hard though it may be to discern a consistent shape to Cameron’s foreign policy, he succeeded in keeping Britain safe, improving the relationship with the US after the Brown years and in promoting the British brand abroad.

But these years were not a time of heroes. Other national leaders in the West struggled to assert themselves on the world stage. Obama, François Hollande, and leaders across the EU all experienced difficulties given the economic climate, the rise of China and India, Vladimir Putin’s aggression in Ukraine, and militant Islam’s success in Syria and Iraq. Only Merkel in Germany emerged with credit from these problematic years, though continuing difficulties facing the eurozone and in finding a solution to migration dented her authority. Ultimately, the failure of Cameron’s European gamble will cast a long shadow over his foreign policy record.

David Cameron’s calm stewardship of the coalition government of 2010–15, and his piloting Britain through profound economic weakness back to economic vitality, will be his greatest achievements. His record during these years compares favourably to the first terms of Thatcher and Blair. By defying the odds in winning the 2015 general election, he led his party back into office with an overall majority, a signal personal achievement. Ultimately, he could not prevail against the juggernaut of Euroscepticism in his own party, the press and country. The Conservative Party has not been as divided on any issue since the 1840s, while the nation has not been so divided since the Suez Crisis in 1956. His strengths were his high intelligence, work rate, calm under pressure, integrity and courage. His failings – impetuosity, naivety at times and lack of strategic clarity – were those of a young man. The youngest prime minister for one hundred and ninety-eight years, he was arguably at the peak of his powers when he fell on his sword.

The first six months of his second term showed considerable promise in carving out a distinctly personal agenda focusing on what became known as the ‘life chances’ agenda. The commitment to One Nation Toryism that he made on the steps of Number 10 after his 2015 election victory now lies unfulfilled. To his closest supporters and aides, Cameron’s inability to execute this agenda, which had only begun to crystallise, is one of the tragic consequences of the European referendum. No one knows how the remaining two or three years of his second term would have panned out had the country voted differently. We will never know what David Cameron might have achieved had he not departed in 2016. History tends to condemn prime ministers for one major mistake – Lord North for the loss of the American colonies, Anthony Eden for Suez and Blair for Iraq. It would be cruel and wrong for Cameron’s premiership to be so castigated. He achieved much during his six years. We believe he had little or no choice but to call a Referendum and that he could not have done more to achieve the terms he did in February 2016. But he should have delayed calling the Referendum till better terms were given, difficult though it would have been, and fought a more positive, authoritative campaign.

Anthony Seldon and Peter Snowdon

July 2016