Читать книгу Freedom in Our Lifetime - Anton Lembede - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

ROBERT R EDGAR

LUYANDA KA MSUMZA

On Easter Sunday 1944 a group of young political activists gathered at the Bantu Men’s Social Centre in downtown Johannesburg to launch the African National Congress Youth League (ANCYL). Motivated by their desire to shake up the “Old Guard” in the African National Congress (ANC) and set the ANC on a militant course, this “Class of ’44” became the nucleus of a remarkable generation of African leaders: Nelson Mandela, Oliver Tambo, Walter Sisulu, Jordan Ngubane, Ellen Kuzwayo, Albertina Sisulu, A P Mda, Dan Tloome and David Bopape. Many of them remained at the forefront of the struggle for freedom and equality in South Africa for the next half century.

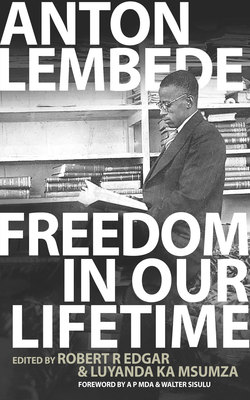

However, the person the Youth Leaguers turned to in 1944 for their first president is not even listed in this group. He was a Natal-born lawyer, Anton Muziwakhe Lembede. Known to his friends as “Lembs”, Lembede was a political neophyte when he moved from the Orange Free State to Johannesburg in 1943 to practice law. His sharp intellect, fiery personality, and unwavering commitment to the struggle made an immediate impression on his peers, and he was quickly catapulted into prominence in both the Youth League and the ANC. Though his political life was brief – he died tragically in 1947 – he left an enduring legacy for future generations. He is best remembered for his passionate and eloquent articulation of an African-centred philosophy of nationalism that he called “Africanism”. A call to arms for Africans to wage an aggressive campaign against white domination, Africanism asserted that in order to advance the freedom struggle, Africans first had to turn inward. They had to shed their feelings of inferiority and redefine their self-image, rely on their own resources, and unite and mobilise around their own leaders. Though African nationalism remains to this day a vibrant strand of political thought in South Africa, Lembede stands out as the first to have constructed a philosophy of African nationalism.

As South Africa enters a new era, we have decided to remember Lembede’s contribution to the freedom struggle by assembling this collection of writings by and about him. Writing about Lembede is a challenging task for several reasons. One is that we are still faced with significant gaps in our knowledge of his life, especially the years before he moved to Johannesburg and entered politics. Another is that Lembede did not have the opportunity to develop many of his ideas fully because of the short time period in which he was politically active. Consequently, it is difficult to chart precisely the evolution of his political ideas. However, we believe this collection, which brings together Lembede’s writing from his student days to just a few days before his death, significantly broadens our understanding of a seminal figure in South African political thought.1

We have divided this collection into eight sections. The first consists of essays he wrote in the 1930s when he was a student at Adams College and, later, a teacher in Natal and the Orange Free State. Subsequent sections present his political writings from 1944–47 when he was active on the political scene and began to frame his philosophy of African nationalism. His views on African nationalism, religion, the ANC Youth League, cultural affairs and other political movements were primarily set out in letters and essays he submitted to the black press. But we have also included reports on his speeches, a book review, excerpts from his MA thesis for the University of South Africa and reactions to his activities and ideas. Finally, we have included tributes to Lembede by his contemporaries on his death.

EARLY LIFE AND EDUCATION

Looking back on his childhood days in Natal, Lembede was fond of telling his Johannesburg friends, “I am proud of my peasant origin. I am one with Mother Africa’s dark soil.” This declaration served a dual purpose: defining a political orientation and commitment and underscoring the fact that whatever his considerable educational, professional and political achievements, he remained strongly attached to his rural roots.

Born on 21 January 1914 on the farm of Frank Fell at Eston, Muziwakhe Lembede was the first of seven children of Mbazwana Martin and Martha Nora MaLuthuli Lembede.2 His father was a farm labourer who, according to his family, had a reputation among whites and blacks in his area for “listening, thinking … and … a quality of the fear of God which he impressed upon his children by deeds.”

His mother attained a Standard V education (a considerable achievement for any black South African at that time) at Georgedale School and taught at schools at Vredeville, Darlington, and Umlazi Bridge. She tutored Anton at home in the basics of reading and writing until he was ready to pass Standard II. But she was anxious for him and her other children to escape their gruelling lives as farm labourers. Around 1927, she prevailed on her husband to relocate the family to Mphephetho in the Umbumbulu “native” reserve (situated mid-way between Pietermaritzburg and Durban) so that their children could have access to formal schooling.

The Lembede family history portrays their move to Umbumbulu as a positive one, but it is also coincided with a major upheavel on Natal’s white farms. For a variety of reasons, white farmers evicted thousands of black South Africans from their farms in the late 1920s. Most of the dispossessed made their way to the urban areas or the overpopulated, overstocked and unproductive African reserve areas that comprised roughly seven per cent of South Africa’s land. Indeed, Lembede’s father could not make ends meet on his plot of land at Mphephetho, and he had to supplement his income by working as a seasonal labourer on nearby white and Indian farms.3

Before the Lembede family moved to Umbumbulu, Muziwakhe, who had been baptized in the Anglican church and given the name Francis, converted to Catholicism and, with his father and brother Nicholas, joined a Roman Catholic church near Eston. The priest at Eston, Father Cyprian, gave Muziwakhe an additional name, Anton.

The church was to play a central role throughout Anton’s life. As teenagers, he and Nicholas often played a game in which they acted out the role of a priest. Indeed, both told their family that they intended to become priests. However, Anton promised that before joining the priesthood, he would teach for a few years to pay school fees for his brothers and sisters.

Anton’s formal education did not begin until he was thirteen, but he showed immediate promise in his classes. His teacher at the Catholic Inkanyezi school was nineteen year old Bernadette Sibeko of Ladysmith, who was fresh out of Mariannhill Training College. Inkanyezi was her first teaching post.

About sixty students squeezed into her classroom in a “building made of wattle and daub with corrugated iron roofing but with no ceiling.”4 To Standard I and II students, she taught Zulu, English, hygiene and scriptures. In addition, to Standard III and IV students, she taught nature study, short stories from South African history, regional geography and reading, writing and arithmetic.

Sibeko was the sole teacher for all the classes, and one of her techniques for coping with such a large and diverse group of children was to parcel out responsibilities. Since Anton was one of her best students, she often taught him a lesson and had him instruct the others.

Anton’s dedication to his studies left distinct impressions on both his family and Sibeko. His family remembers him herding the family cattle, but being so engrossed by his books that he let the cattle wander off. One of Sibeko’s recollections was of watching him at a football match, walking up and down a field in deep thought and occasionally kicking the ball when it came his way.5

On one occasion, Sibeko asked Anton to write an essay on money. His response, written out on a slate with a pencil, so impressed her that she copied it and entered it in a contest at a teachers’ conference. It was awarded first prize. When we interviewed her in August 1992, she had no hesitation recollecting his short essay.

Money is a small coin, a small wheel bearing the picture of the King’s head. Round this head is an inscription – head of the King of England – George V. You can go to any store. If you present this coin the store-keeper gives you whatever you want. The nations know the value of money, and we too realise that money rules the world.

After Anton completed Standard III, Sibeko encouraged him to continue his education. He worked for a while in a kitchen at Escombe in order to buy books and pay school fees at Umbumbulu Government School, where he completed Standard VI with a first class pass. Then, Hamilton Makhanya, a local school inspector, assisted him in securing a scholarship at nearby Adams College.

ADAMS COLLEGE

Established in 1849 to train African assistants to European missionaries, Adams College had by the 1930s become one of the premier schools for African students from all over southern and central Africa.6 Adams had three divisions: a high school which took students through matriculation; an industrial school for training students in carpentry and building; and a teachers’ training college, opened in 1909. A new teachers’ course introduced in 1927 prepared students for the Native Teachers Higher Primary Certificate (later renamed the T3), which allowed a teacher to apply for jobs in Intermediate Schools, High Schools and Training Colleges. This was the course for which Lembede enrolled in 1933.

Lembede left indelible impressions on his classmates at Adams. First, there was his abject poverty which was apparent to everyone because of his shabby dress: his patched pants and worn-out jackets. Jordan Ngubane, a classmate and one of the founders of the ANC Youth League, described Lembede as the “living symbol of African misery.”7 Girls were embarrassed to be seen with him in public. Lembede was “very stupid in appearance,” one female classmate recollected. “If any girl ever saw you, even if Antony [Anton] was innocently talking with you, then you’d become somebody to be talked about for the day.”8

But there was another side of Lembede that his classmates consistently commented on, his brilliance and dedication to his studies. Edna Bam, who later taught in the faculty between stints at the National University of Lesotho, drew a comparison between Lembede and J E K Aggrey, the Ghanaian-born educator who had addressed an Adams audience in April 1921 when he visited South Africa as part of the Phelps-Stokes delegation investigating African education.9 Aggrey was touted as the role model for all aspiring African students. Bam and other Adams students were told stories about Aggrey being so dedicated to his schooling that in the middle of winter he studied with his feet in a bucket of hot water. And that was the image that came to mind when she remembered Lembede.

Lembede excelled in learning languages. At Adams he picked up Afrikaans, Sesotho and Xhosa as well as German from German nuns residing near Adams, and he began studying Latin. Learning Afrikaans was even then regarded sceptically by black students. But Ellen Kuzwayo recollected an occasion where Lembede spoke before a group of students preparing for a debate with students at Sastri College, an Indian school in Durban. He started off his speech in English, but then switched easily to Afrikaans.

In one of his student essays in the Adams’ publication, Iso Lomuzi, Lembede advised that the best way to learn new languages was to combine the techniques of learning grammar with reading elementary readers.10 In that same essay, he maintained that studying foreign languages allowed one to understand other people and that contributed to lessening racial hatred. However, he also supported blacks learning languages other than their own in order to put them in a position to challenge whites who had established a monopoly over African languages through their control of orthography and publications. “It speaks for itself,” he stated, “that we want educated Bantu men who have studied various Bantu languages, and who will be authorities on them.”

Two other student essays, “The Importance of Agriculture” and “What Do We Understand by Economics?”, provide a glimpse into Lembede’s thinking on political and economic issues.11 In them, he placed responsibility for black poverty on the African people themselves. He charged that poor farming techniques and the laziness of black farmers were directly responsible for their failures. Instead of drawing a connection between government policies and land shortages, he faulted black farmers for reducing themselves to the level where they had to seek work on white farms for a pittance. Lembede’s own father had been forced to supplement his family’s income by periodically going out to work on the farms of neighbouring white and Indian farmers.

Lembede’s solution was an education that taught people an appreciation for manual labour and applied modern agricultural techniques. His role model was Booker T Washington, the black American educator, whose ideas on industrial education and self-help had been transplanted to Natal in the early twentieth century by an American-trained Zulu, John Dube. Washington’s principles permeated Dube’s own school, Ohlange Institute, and they had a significant impact on the thinking of those in charge of education throughout South Africa in the following decades.

Lembede’s student views are a pointed contrast to his criticisms of the government in the mid-1940s, but they highlight themes that consistently surface in his later writings – that Africans had to rely on their inner resources to overcome inequities and that spiritual beliefs were a necessary component of economic and political advancement.

The fact that Lembede’s essays were not overtly political is not surprising since descriptions of Adams generally agree that the school did not have a politicised environment. Although Adams teaching staff included Albert Luthuli and Z K Matthews, who were to become prominent figures in the ANC, its administrators and teachers carefully insulated students from the political currents circulating about them. There was nevertheless one aspect of Adams that possibly influenced Lembede’s nationalism of later years, a conscious effort on the part of Adams administrators to defuse ethnic tensions between students.

In this regard, a highlight of the school year was Heroes of Africa Day, set aside to celebrate heroes of the African past. The campus had recognised Moshoeshoe Day and Shaka Day in the past, but when Edgar Brookes took over as Adams’ principal in 1934, he created a Heroes’ Day on 31 October, the eve of All Saints Day, when “heroes” of the Christian faith were honoured.12 On Heroes’ Day, students wore their national dress and gathered at an assembly to pay tribute to noted black South African figures. An Adams student, Khabi Mnqoma, has described the day’s significance:

The day is set aside to sing praises to heroes of South Africa, and to attempt to recapture the mode of life of our ancestors. As Adams College is what one might term cosmopolitan, the various students contribute towards drawing a picture of primitive African life.13

Ellen Kuzwayo recalls her feelings about the day:

We crossed the tribal division on that day … If I was Tswana, I had a freedom to depict my hero in another community in that cultural dress. Because I lived very near Lesotho, my grandfather’s home … and I saw more of the Basotho people, saw their traditional dresses, their traditional dances, everything, and I would be nothing but a moSotho … And I think we didn’t realise it … but it kept us as a black community without saying, “You are Zulu. You are Tswana. You are Xhosa.”14

TEACHING AND THE LAW

After leaving Adams in 1936, Lembede took up a series of teaching posts, first at Utrecht and Newcastle in Natal and then in the Orange Free State at Heilbron Bantu United School, where he taught Afrikaans, and Parys Bantu School, where he was headmaster.

His thirst for education never stopped. Over the next decade he steadily advanced himself through a series of degrees, all through private study and financed with his meagre personal resources. He passed the Joint Matriculation Board exams in 1937, taking Afrikaans A and English B and earning a distinction in Latin. In 1940 he studied for a BA, majoring in Philosophy and Roman Law, through correspondence courses with the University of South Africa. He then tackled the Bachelor of Laws (LLB) through the University of South Africa, completing it in 1942. Finally, he registered for an MA in Philosophy in 1943 at the University of South Africa, submitting his thesis entitled “The Conception of God as Expounded by, or as it Emerges from the Writings of Philosophers – from Descartes to the Present Day” in 1945.15 Considering the fact that only a few black South Africans had attained graduate degrees, A P Mda’s tribute to Lembede on completing his MA was well-deserved: “This signal achievement is the culmination of an epic struggle for self-education under severe handicaps and almost insuperable difficulties. It is a dramatic climax to Mr Lembede’s brilliant scholastic career.”16

Lembede’s ascetic lifestyle and his disciplined, austere study regimen were a major part of his educational success. According to B M Khaketla, his roommate in Heilbron, Lembede would wake up at five and read until six, then he prepared for school.17 He taught from eight until one. After lunch, at two, he came directly home and studied until seven o’clock when he broke for his evening meal. After dinner, he studied until eleven. He followed this timetable religiously on weekdays. On Saturdays, he read from five in the morning until lunch. After lunch he read until he went to bed. Sundays he set aside for church, reading newspapers and socialising.

Lembede also participated in the Orange Free State African Teachers’ Association, an organisation he scathingly censured in a letter to Umteteli wa Bantu (8 November 1941).

Every year, many resolutions are adopted by the Conference. What is the fate of many of them? Some end just on the paper on which they are written. They are not acted upon, thus they fail to realise their ultimate destiny – action … We must be action-minded. The philosophy of action must be the cornerstone of our policy … In our ranks we have men and women of high talent and ability. Our poor, disorderly position is not occasioned by lack of talent, but (a) by lack of scientific organisation and utilisation of that talent, (b) by lack of will-power. Africans! Our salvation lies in hard and systematic work!

Never one to hold back his criticisms of shortcomings, Lembede’s impatience with the Association’s inaction and lax discipline and his desire for positive action foreshadowed sentiments that made their way into his political views several years later.

Lembede also attended church services of the African branch of the Nederduitse Gereformeerde Kerk (Dutch Reformed Church [DRC]), where he occasionally translated Afrikaans sermons into seSotho. Khaketla was struck by Lembede’s fluency in both languages, and that he was willing to attend and appreciate services of other denominations. His attitude was that “God is indivisible”. He put on his best clothes and prepared himself for the monthly nagmaal services. Lembede thought nagmaal (Holy Communion) was more graceful and meaningful than the Holy Communion celebrated in the Catholic church; and he even told Khaketla, an Anglican, that he could never understand the joy of nagmaal because Anglicans celebrated communion too frequently.

This is a pertinent anecdote because much has been made of Lembede’s attachment to the Catholic church. Khaketla recollected that, during one vacation, he went to Johannesburg and met Lembede by chance at Park Station. Lembede invited him to visit a friend, A P Mda, in Orlando township. As they approached the Roman Catholic church in Orlando, they saw Mda in the churchyard. Khaketla recognised Mda because they had trained together as teachers at Mariazell school near Matatiele. Lembede asked Khaketla not to tell Mda that he had regularly attended DRC services in Heilbron. To Lembede, church affiliation did not mean as much as a belief in God. Moreover, participating in the DRC had partly been a tactic to get a job. He represented the DRC at Bantu United School, where every sponsoring denomination had to be represented on the staff.

An interesting sidelight of Lembede’s stay in the Orange Free State was his search for a wife. According to his Parys roommate Victor Khomari, Lembede had a great reverence for educated women.18 He vowed that he wanted to meet and marry the most brilliant woman he could find rather than confining himself to someone from within his own ethnic group. When he read in the press about a woman from Lesotho who had been a spectacular student at Morija Training College and the University College of Fort Hare, he decided to go to Mafeteng in Lesotho with Khomari on their school holiday. Khomari loaned him a bike to peddle to Thabana Morena, the school where the woman was teaching, but he was not able to meet her. By coincidence, the young woman in question, Caroline Ntseliseng Ramolahloane, later married B M Khaketla, Lembede’s Heilbron roommate, in 1946.

One of Lembede’s last acts before moving to Johannesburg was to contact J D Rheinallt Jones, Director of the South African Institute of Race Relations, in June 1943, offering to do research for the Institute during the July vacation period. Rheinallt Jones asked Lembede to conduct a study of how black South African youths became “delinquents” by examining the records of the Diepkloof Reformatory to determine how young people had run foul of the law. In accepting the offer, Lembede replied: “I think the work will be of some educative value to me also; and I hope my knowledge of Zulu, Sesotho and Afrikaans will help me a lot in the investigation.”19 We do not have any record of the study that Lembede was commissioned to carry out, but his experience is probably reflected in the occasional comments on the deleterious impact of urban life on African youth that were woven into his political essays.

JOHANNESBURG

When Lembede had finished his LLB, he took up an offer to serve his articles with the venerable Pixley ka Seme, who had established one of only a handful of black law firms in Johannesburg. After practicing law for over three decades, Seme was in poor health and on the verge of retirement, and he was looking for someone to take over his practice. His law career had had its less than distinguished moments. In 1932 he was struck from the roll of attorneys in the Transvaal, but was reinstated in 1942.20

He had also been a founding father of the ANC in 1912, and had served as its president from 1930 to 1937. A conservative, autocratic figure, Seme’s presidency was marked by discord, and when he was ousted as president, he left the ANC at a low ebb. By the time Lembede began to work in his law firm, Seme was no longer a major player in ANC politics.

Whatever vicissitudes Seme had experienced in his legal and political careers, Lembede held him in high regard. Moreover, because Seme was still a respected figure, he certainly eased Lembede’s entry into Johannesburg’s political and social circles.21 In 1946, after Lembede had served his articles, Seme made him a partner. An Umbumbulu businessman, Isaac Dhlomo, loaned Lembede £500 to buy into Seme’s firm.22

Lembede’s law career was brief, but his linguistic abilities and his uniqueness as a black South African lawyer provided some memorable moments. One was when he shocked a magistrate in Roodepoort by conducting his case in Afrikaans. Another was when Lembede broke into Latin in a magistrate’s court in Johannesburg, prompting the magistrate to interrupt and implore him: “Please, Mr Lembede, this is not Rome, but South Africa.”23

On another occasion Lembede appeared in a criminal case in a Pretoria court. The court officials were either unaware that there was a black attorney practicing or did not want to acknowledge him. So when Lembede arrived and informed the prosecutor that he was the attorney of record, the prosecutor brushed him off. Lembede responded by sitting in the public gallery. When his case was called, Lembede jumped up and announced from the gallery that he was appearing for the accused. The magistrate was taken aback by a person from the gallery claiming to be a lawyer and called the prosecutor and Lembede into his chambers. Lembede came out to represent the defendant. The incident caused a stir among the black South Africans in the gallery, primarily because they, too, were unaware that there were black attorneys, and because of the boldness of Lembede in challenging the prosecutor.24

After moving to Johannesburg, Lembede also renewed his friendship with A P Mda, whom he had first met in 1938 at a Catholic teachers’ meeting in Newcastle. The two exchanged addresses, and when Lembede had occasion to visit Johannesburg, he would look up Mda. Born in 1916 in the Herschel district, near the Lesotho border, Mda had also received a Catholic education and earned his Teachers’ Diploma at Mariazell. He moved to the Witwatersrand in 1937 and, after taking up a variety of jobs, he landed a teaching post at St. Johns Berchman, a Catholic primary school in Orlando Township. He rapidly rose to prominence in the Catholic African Union, the Catholic African Teachers’ Federation and the Transvaal African Teachers’ Association. In the latter organisation, he became a leading figure in the campaign to improve teachers’ salaries and conditions of service.

He was also a veteran of political organisations. He had been baptised into politics by attending the All African Convention (AAC) meeting in Bloemfontein in 1937. But he soon grew disenchanted with the AAC and moved into the ANC when it was revitalised in the late 1930s. Mda was clearly more politically experienced than Lembede. As Ngubane put it, living on the Witwatersrand had seasoned Mda as a political thinker and “as a result he had more clearly-defined views on every aspect on the race problem.”25

For a while Mda and Lembede shared a house in Orlando. And as Lembede wrote his MA thesis, they became “intellectual sparring partners”.26 Mda sharpened Lembede’s understanding of philosophical ideas by assuming opposing positions on issues and vigorously debating them with him. Mda was the perfect foil for Lembede because he loved the cut and thrust of debate, and he doggedly defended his positions with as much fervour as Lembede. Mda remembered their exchanges this way:

I had to defend a certain position while he attacked it … He wanted to gain some clearer understanding of the subject matter he was studying. He used me as a tool to achieve that goal . . .27

In the same manner, the pair took on the major political questions of the day. There were occasions, though, when Mda and other Youth Leaguers had to curb Lembede’s instinctive bent to take extreme positions. When Lembede was living in the Orange Free State, in order to improve his command of Afrikaans, he began reading Hendrik Verwoerd’s column, “Die Sake van die Dag”, in Die Transvaler, the ultra-nationalist Afrikaans newspaper, and imbibing his ideas. As a result, after Lembede moved to Johannesburg, “Mda found Lembede rather uncritically fascinated with the spirit of determination embodied in fascist ideology, to the point where he saw nothing wrong with quoting certain ideas of Hitler and Mussolini with approval.”28 In the Orange Free State Lembede did not have the benefit of having peers who could scrutinise and refine his thinking, but in Johannesburg, he had Mda and others who challenged him – not always successfully – to rein in some of his extremist ideas. For instance, Mda forced Lembede to rethink his fascination with fascism by pointing out Hitler’s ideas about racial superiority and how they specifically applied to black people. By the close of the Second World War, Lembede was unequivocally rejecting fascism and Nazism in his writings.

Mda and Lembede found common ground on many political issues. And out of their discussions with each other and with their peers emerged a vision of a rejuvenated African nationalism – centred around the unity of the African people – that could rouse and lead their people to freedom.

THE FOUNDING OF THE ANC YOUTH LEAGUE, APRIL 1944

The years of the Second World War saw a quickening of the pace of protest on the Witwatersrand.29 The immediate cause of this ferment was the war itself, as a consequence of which South Africa’s manufacturing and mining sectors dramatically expanded to supply goods and arms for the war effort. The economy boomed, and as white workers were siphoned off into the army, tens of thousands of black men and women, fleeing the stagnation of the rural areas, poured into the urban areas seeking jobs. Between 1936 and 1946 roughly 650 000 people moved into the urban areas. During those same years, Johannesburg’s population leaped from 229 122 to 384 628, almost a seventy-five per cent increase.

The wartime economy may have opened up employment opportunities for black workers, but at a cost. Prices of basic goods soared, housing shortages grew more acute and municipalities charged higher prices for public transportation. White government and municipal officials did little to alleviate these burdens, and as a result a series of protests – bus boycotts, squatter protests and worker strikes – were triggered off in townships throughout the Witwatersrand.

By and large, ANC leaders remained aloof from these protests. For the ANC the 1930s had been years of inaction and the All African Convention (AAC) had taken advantage of the ANC’s lethargic leadership by eclipsing it as the pre-eminent vehicle for black opinion during and after the controversy over the Hertzog Bills. By the late 1930s, however, a group of activists, unhappy at a lack of direction and the compromises made by AAC leaders, turned to resurrecting the ANC.

An important step in the ANC’s revitalisation was the election (by a slim majority of twenty-one to twenty) of Dr A B Xuma as ANC president in 1940. Xuma, who had a flourishing medical practice in Johannesburg, rescued the ANC from its parlous economic condition by raising dues, soliciting donations from private sources and contributing some of his own resources.

He also pushed through a new constitution in 1943, eliminating an Upper House of Chiefs. He toured throughout South Africa, imposing discipline and shoring up support among provincial ANC congresses. He opened a national office for the ANC in Johannesburg in December 1943. And he put the ANC in a position to respond to day-to-day situations by setting up a small working committee of people who lived within a fifty-mile radius of Johannesburg.30

There was no question of Xuma’s commitment to equal political rights and the abolition of discriminatory laws, but he remained wedded to bringing about change through constitutional means. Although he was not at heart comfortable with mass protest and he was wary of the ambitions of younger ANC members, he understood that the ANC could not survive unless it brought younger members into its fold.

The inspiration for forming a Youth League came from several different quarters.31 One influence were the numerous youth and student organisations that had sprung up around the country. For instance, in 1939 Mannasseh Moerane, principal of Umpomula High School, and Jordan Ngubane, a journalist, founded the National Union of African Youth (NUAY) in Durban to promote literacy, economic and business training and political advancement. Without openly declaring it, they also intended to build an organisation capable of breaking A W G Champion’s personal stranglehold over the Natal wing of the ANC.32

Several future Youth Leaguers – Oliver Tambo, Congress Mbata, Lancelot Gama, William Nkomo, Nelson Mandela, Lionel Majombozi, James Njongwe and V V T Mbobo – also emerged from the mid-1930s at Fort Hare, the university college founded for black, coloured and Indian students in 1916. By the outbreak of the Second World War several hundred students from all over southern Africa were studying for degrees at Fort Hare, and a number of them were intensely engaged in debating the political issues of the day: the abolition of the Cape franchise, the creation of a Natives Representative Council (NRC), the Italian invasion of Ethiopia and the contest for global supremacy and its implications for Africans.

In the early 1940s Fort Hare students also received a bittersweet introduction to protest politics through their involvement in two strikes. The first was touched off in September 1941 after the white supervisor of the dining hall struck a black female employee. Over three quarters of the students showed their sympathy with the worker by boycotting classes for three days. The Fort Hare administration had no sympathy for the strike and the issues raised by the students. They demanded that strikers submit a formal letter of apology for their actions and pay a fine of £1 or be suspended. All but one complied.

The second strike, in September 1942, came about when Bishop C J Ferguson-Davie, the warden at Beda Hall, the residence for Anglicans, turned down a request by Beda students to play tennis on Sunday. When the majority of Beda students refused to acknowledge Ferguson-Davie’s authority in other forums, such as chapel, he demanded that they sign a formal apology; if they did not they would be suspended from the university. Most of the students refused to sign the apology, and forty-five of the sixty-four Beda students, including Ntsu Mokhehle and Oliver Tambo, were suspended for varying periods of time.33

Another route to the Youth League was through the aggressive campaign of the Transvaal African Teachers’ Association to improve the paltry wages and poor working conditions of black teachers. Teachers like A P Mda and David Bopape played prominent roles in educating and mobilising their communities behind the teachers’ grievances. A high point of the teachers’ protest was a march through downtown Johannesburg in May 1944 that reinforced a belief among its participants that militant resistance to the government could produce positive results. Teachers were to form a significant constituency in the Youth League.

A final factor that produced the Youth League was the challenge posed to the ANC by the newly formed African Democratic Party (ADP), which featured two dynamic young leaders, Paul Mosaka and Self Mampuru. Mampuru had sought support from ANC youth when he considered standing for the presidency of the Transvaal ANC in 1943, but he had suddenly jumped to the ADP. Fearing the ADP would siphon off younger ANC members, Xuma cultivated relationships with youth leaders. And he responded positively when they proposed establishing a Youth League within the ANC.

Whatever their backgrounds, the common denominator for young ANC activists was their impatience with the unwillingness of the ANC “Old Guard” to adopt militant tactics to contest white rule. In the latter half of 1943 they began holding meetings to discuss forming a youth wing in the ANC. A formal proposal to found a Youth League was put forward at the December 1943 meeting of the ANC in Bloemfontein, where pressing issues such as the approval of “African’s Claims in South Africa”, a policy statement that spelled out ANC objectives as well as a Bill of Rights and the relationship between the AAC and ANC were on the agenda. Youth leaders introduced and passed a resolution, proposed by Moerane and seconded by Mda, that stated: “ … henceforth it shall be competent for the African youth to organise and establish Provincial Conferences of the Youth League with a view of forming a National Congress of the Youth League immediately.”34

After winning the blessing of Xuma, who overcame his misgivings about the ideas and roles of Youth Leagues within the ANC, the Youth League issued its manifesto in March 1944 and held its inaugural meeting at the Bantu Men’s Social Centre the following month.35 Speakers included Lembede, Mda and V V T Mbobo, as well as senior Transvaal ANC leaders such as R V Selope Thema, E P Moretsele and Xuma. Youth Leaguers selected W F Nkomo and Lionel Majombozi, medical students at Witwatersrand University, as provisional chair and secretary respectively, until the Youth League drafted a constitution and conducted a formal election for officers.

Nkomo and Majombozi enjoyed popularity among Youth Leaguers, but they were viewed as transitional appointments since it was known they would have little free time as students. In addition, Nkomo’s leftist leanings troubled nationalists in the Youth League such as Mda and Lembede, who believed Nkomo was secretly a member of the Communist Party of South Africa (CPSA). A tip-off, according to Ngubane, was Nkomo’s suggested wording for the Youth League manifesto “which in our opinion would have given it a slightly communist slant.”36

However, a political showdown was unnecessary. When Youth League elections took place in September, Nkomo stepped aside to concentrate on his studies. Lembede was then elected first president of the Youth League, a position he held until his death.

Lembede had already begun making his mark on Youth League policy when Youth Leaguers delegated him, Ngubane and Mda to draft the Youth League manifesto adopted in March 1944. Like Lembede, Ngubane was an Adams product and a newcomer to the Witwatersrand. He had been a reporter for John Dube’s Ilanga lase Natal before moving to Johannesburg in 1943 to become an assistant editor at Selope Thema’s Bantu World. Ngubane, Lembede and Mda were all Catholics and implacable opponents of the Communist Party.

The manifesto remains a classic statement of the African nationalist position. The conflict in South Africa, it asserted, was fundamentally a racial one between whites and blacks, who represented opposite political and philosophical poles. The oppressors, whites, represented a philosophy of personal achievement and individualism that fuelled fierce competition; the oppressed blacks embodied a philosophy of communalism and societal harmony where society’s needs were favoured over those of the individual. Because whites had defined their domination in terms of race, this had led blacks “to view his problems and those of his country through the perspective of race.”

The manifesto was also a blistering indictment of the orthodoxies that black and white leaders had been wedded to for decades. One was trusteeship, an idea promoted by white politicians that blacks were their wards who had to be brought along slowly to a civilized state. The manifesto surveyed the long litany of government laws that had hindered, not advanced blacks, and concluded that trusteeship was a bluff aimed at perpetuating white rule.

Another orthodoxy was the belief of ANC leaders that change could come through compromise and accommodation. The Youth Leaguers charged that senior ANC leaders had grown remote from the black community and were trapped between their apprehensions over losing the few privileges the government granted them and their qualms over mass protest bringing down the wrath of the government. The result was that ANC leaders had become “suspicious of progressive thought and action” and offered no innovative policies or strategies for combatting “oppressive legislation”. They were so locked into segregationist structures, such as the Natives Representative Council (NRC), that they had drifted away from the ANC’s original vision and vitality.

The manifesto’s criticisms of ANC leadership were devastating, but rather than calling on people to defect from the ANC, it invited Youth Leaguers to remain loyal and serve as “the brains-trust and power-station of the spirit of African nationalism” and infuse the ANC with a new spirit. The manifesto’s political goals were clear: self-determination and freedom for black South Africans. But other than calling for a radical reversal of ANC policies, the manifesto did not clearly spell out alternative strategies. This tactical omission was not addressed until after Lembede’s death, when the Youth Leaguers launched their drive to pressure the ANC to adopt a programme of action.

That Lembede was a relative newcomer to Johannesburg and politics did not hamper his rapid rise to prominence in the Youth League and parent ANC. This can be attributed to several factors. One was that he was a lawyer, serving his articles with Seme, and thus in a prestigious position looked upon favourably by the ANC “Old Guard”, who did not take anyone seriously who lacked education or status. Another was that Lembede had completed his legal studies and was therefore relatively immune to direct government pressure. Many of the Youth Leaguers were teachers, and they, like Moerane, had to tread cautiously when it came to their political activism.

Moreover, there was no question over Lembede’s leadership qualities and his zealous devotion to Youth League causes. A tenacious debater and a stirring orator, he showed no hesitancy in staking out contentious positions and promoting them fearlessly in any setting and against any adversary. Even within the Youth League, which had a strong left-of-centre faction, Lembede had to defend his Africanist positions against charges that they were too extreme. Congress Mbata recollected: “He was almost alone and he fought a very brave battle; I must say we respected him for his stand. He was a man who if he was convinced about a thing would go to any length to make his viewpoint.”37

Whatever reservations Youth Leaguers had with Lembede’s ideas and his lack of grounding in practical politics, they recognised that he was willing to take on any challenge, no matter how much opposition it provoked. An example was Lembede’s call for leaders to boycott the NRC, set up by the government in 1937. The government never intended the NRC to be more than an advisory board, but conservative and moderate leaders (including some prominent ANC officials), hoping to exploit the NRC as a platform for expressing black opinion, decided to participate. However, the NRC remained an irrelevant talk-shop.

To Youth Leaguers, the real issue was full political rights for all South Africans, and they appealed to black leaders to refrain from participating in NRC elections. In the aftermath of the 1946 mine workers strike, Lembede introduced a resolution at the ANC national conference calling on NRC members to resign immediately. However, most senior ANC leaders, including prominent communists, argued that a boycott would not succeed unless there was unanimity about the strategy within the black community. Otherwise, some black politicians would participate in the NRC and do the government’s bidding. When Lembede’s resolution was overwhelmingly defeated, it was further proof to the Youth Leaguers of how out of touch ANC leaders were with the militant mood in the black community. “The masses are ready to act,” Lembede challenged the ANC national executive, “but the leaders are not prepared to lead.”38

Although Lembede’s stances provoked harsh reactions, he never shied away from controversy. Indeed, he seemed to revel in it. Mda recalled a meeting in Orlando where he and Lembede shared a platform. Lembede thought the meeting was not lively enough, so he deliberately stirred things up by launching an attack on the Communist Party. The meeting, according to Mda, provoked a ferocious response from the Communist Party newspaper Inkululeko. Quoting a member of the audience, Inkululeko reported: “He spoke firmly but like a qualified Nazi. In fact, if one were to close one’s eyes, one would certainly think one was listening to Hitler broadcasting from Berlin.’”39

Joe Matthews recounted another occasion where Lembede and Mda were invited to address the debating society in the geography room at St. Peter’s School, where Youth Leaguers Oliver Tambo and Victor Sifora were teaching.

So Lembede got up, and he was dressed … in a black tie, black evening dress, which in itself was quite something. And he started off, “As Karl Marx said, ‘A pair of boots is better than all the plays of Shakespeare.’”

This provocative statement roused his predominantly student audience, but it also prompted a sharp retort from the school’s geography teacher, Norman Mitchell, a devotee of the British Empire, who angrily shouted back, “That’s not true.”40

A PHILOSOPHY OF AFRICAN NATIONALISM

In South Africa, “nation” and “nationality” have been elastic concepts whose boundaries have expanded or contracted at various points in history according to the relative power or powerlessness of those defining them. A case in point is Lembede, whose starting point for his vision of African nationalism was his recognition of a fundamental political reality: that as long as Africans did not transcend their ethnic divisions, they would remain minor political actors. Unless the continent’s millions of inhabitants agreed to work cooperatively, Africans could not hope to take advantage of global power shifts and compete with established powers such as the United States, Japan, Germany, Russia, England and France and newly emerging ones such as China and India. Moreover, in South Africa, where white domination was perpetuated by dividing the black majority, black unity – based on a shared oppression – was a precondition for challenging the status quo.

Because Lembede’s brand of nationalism was aimed at forging a pan-ethnic identity, he discounted the usual building blocks of nationalism. What bound the peoples of Africa together and made them unique was not language, colour, geographical location or national origin, but a spiritual force he called “Africanism”. This concept first appeared in his writings in 1944, and was based not only on the fact that Africans shared the same continent but that they had adapted to Africa’s climate and environment. “The African natives,” he contended, “then live and move and have their being in the spirit of Africa, in short, they are one with Africa.”41

Borrowing liberally from Darwin’s law of variation in nature, Lembede maintained that because nations differed in the same way as flowers, animals, plants and humans, they had special qualities and defining characteristics. Accordingly, Africa had to “realise its own potentialities, develop its own talents and retain its own peculiar character.”42

This deterministic line of reasoning had a kinship with neo-Fichtean ideas then being advanced by some Afrikaner nationalists. Lembede was certainly familiar with their writings through the Afrikaans press and his MA research. In his thesis, he quoted from a booklet on communism by Nicolaas Diederichs, a professor of Political Philosophy at the University of the Orange Free State and a Broederbond leader.43 Lembede’s ideas mirrored aspects of Diederichs’s philosophy of nationalism, presented in his Nasionalisme as Lewensbeskouing en sy verhouding tot Internasionalisme (1935). For instance, the unifying characteristics of Diederichs’s nationalism was not “a common fatherland, common racial descent, or common political convictions”, but a divinely ordained “common culture”.

Just as He ruled that no deadly uniformity should prevail in nature, but that it should demonstrate a richness and variety of plants and animals, sound and colours, forms and figures, so in the human sphere as well He ruled that there should exist a multiplicity and diversity of nations, languages and cultures.44

No doubt Lembede appropriated some of the ideas of Afrikaner nationalists for his version of African nationalism. While Afrikaner nationalists distorted evolutionary theory to justify white domination, Lembede probably took special delight in recasting the same ideas to promote African equality with Europeans. Moreover, this concept of African nationalism was fundamentally opposed to Afrikaner nationalism. This is illustrated by a story Jordan Ngubane related to Mary Benson, about Lembede having a meeting with a leader of the Ossewa Brandwag (OB), an ultra-nationalist Afrikaner movement. The OB leader told Lembede that “we Afrikaner nationalists realise that no nationalist is an enemy of another nationalist. We have much that is common, land, you are exploited by Jews, English and Indians just as we are by Jews and English, we know that you are suffering and in final record [the] only real friend of a nationalist is another nationalist. We want to make a gesture of friendship.” The OB leader then allegedly handed Lembede a £500 check to be used as Lembede saw fit as a gesture of “goodwill towards African nationalists”. Lembede expressed his appreciation but pointed out that the “goals of Afrikaner and African nationalism [are] irreconcilable therefore [it is] unfair to you and me if I accepted help from your side.” Lembede then walked away.45

Because Lembede did not accept that ideas and innovations were bound by culture, he saw no inconsistency in taking ideas from non-Africans to construct an Africa-centred philosophy. Thus his writings drew on an eclectic range of sources: nineteenth century European romantic nationalists, Greek and Roman philosophers and leaders of Indian, Egyptian and other anti-colonial struggles. He valued the contributions of Western and Eastern civilizations and he argued that Africa was ideally placed to absorb the best from both. However, he warned against uncritically borrowing ideas that had no application on the African continent.46

Lembede’s ideas clearly were Pan African in scope, but it is striking that at no point in his writings did he refer to the Pan African Congress or any of the leading lights of Pan Africanism. Lembede’s ideas, for instance, echo those of Edward Wilmot Blyden, the West Indian/Liberian educator and philosopher who wrote on the creative and distinctive genius of the “Negro” race and the necessity for Africans to express racial pride and forge a unified nationality. Also curiously absent from Lembede’s writings is any mention of Marcus Garvey, the Jamaican-born black nationalist. Garvey’s ideas had not only caught hold in the United States after the First World War, but had also attracted a fervent following in South Africa. There is ample oral evidence that Lembede was familiar with Garvey and he frequently peppered his speeches with quotations from The Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, so why not cite Garvey in his writings? It remains a mystery.47

Lembede is most commonly associated with the framing of a philosophy of African nationalism, but one cannot separate his ideas from the political ends they served. One objective was to create an ideological arsenal for African nationalists in the ANC to combat their principal political rivals, who had staked out clearly-defined doctrines and policies. For instance, the Communist Party of South Africa was rooted in Marxist dogma and regularly issued policy statements. The Non-European Unity Movement, which had an influential Trotskyite wing, had its Ten-Point Programme (a central plank of which was the boycott of government-created institutions), ratified in December 1943. And the African Democratic Party, touting a multiracial membership, had adopted its manifesto in September 1943, advocating change through peaceful negotiation and opposing militant protest. African nationalists were at a disadvantage in proselytising their cause unless they translated their emotions, aspirations and convictions into a logical and coherent set of doctrines independent of European ideologies. In the battle of the “isms”, the Youth League could put forward “Africanism” as an alternative.

In order for Africans to combat white domination, Lembede maintained they had to overcome phychological disabilities. The system of segregation had erected tangible political and economic barriers that were easily targeted, but white domination also had a corrosive impact on the self-image of Africans, and this was more difficult to cope with. This negative self-image was manifested in Africans’ “loss of self-confidence, inferiority complex, a feeling of frustration, the worship and idolisation of whiteness, foreign leaders and ideologies.”48 According to Lembede,

. . . the African people have been told time and again that they are babies, that they are an inferior race, that they cannot achieve anything worthwhile by themselves or without a white man as their “trustee” or “leader”. This insidious suggestion has poisoned their minds and has resulted in a pathological state of mind. Consequently the African has lost or is losing the sterling qualities of self-respect, self-confidence and self-reliance. Even in the political world, it is being suggested that Africans cannot organise themselves or make any progress without white “leaders”.

Now I stand for the revolt against this psychological enslavement of my people. I strive for the eradication of this “Ja-Baas” mentality, which for centuries has been systematically and subtly implanted into the minds of the Africans.49

Lembede’s ultimate cure for these ills was political freedom, but he prescribed several intermediate steps which Africans could take to reassert an independent identity. One was reversing the distorted image of their own past. This meant constructing a history that accentuated the positive achievements of African civilizations, praising the heroic efforts of African leaders who resisted European expansion and resurrecting the glories of the African past. Influenced by Seme, Lembede’s historical vision drew a linear connection between present and past African civilizations, going back to ancient Egypt.

The roots of civilization are deep in the soil of Africa. Egypt is the cradle of civilization not only in the sciences but even in the matter of sharing. Hannibal, conqueror and polygamist, had three black African wives; Moses married an African; neither Europe nor Asia is devoid of African blood. Christ himself, at a young age, found protection in Africa. On His way to Calvary his support came from Africa.50

Lembede had no tolerance for anyone who presented a contrary view of Africans and their history. Reviewing B W Vilakazi’s novel Nje-Nempula, situated during the Bambatha rebellion, Lembede reproached Vilakazi for casting Malambule, a collaborator in Lembede’s eyes, as a lead character because it might “sew [sic] the seed of a defeatist mentality or an inferiority complex in the minds of our children.”

We should not tell our children that we were routed, humiliated and cowed by white people, we should merely tell them that in the face of superior force and weapons, we were compelled to lay down arms … The motto of a National hero should be “My people, right or wrong.”51

Lembede also called on Africans to break their reliance on European leaders by building up their own organisations. In South Africa this meant making the ANC and black leadership central to the national struggle. In this regard, Lembede did not operate in a world of political ambiguity. He spurned appeals to ethnicity, he promoted African national unity over class identities and he rejected Africans merging their cause with other “non-European” groups and sympathetic whites.

For instance, he dismissed the prospect of “Non-European unity” – combining black, coloured and Indian political organisations into one movement – as “a fantastic dream” because they were split along the lines of national origin, religion and culture as well as by their relative positions in the pecking order of segregation.52

Lembede took a rigid and narrow view of Indians: they were merchants who fought “only for their rights to trade and extract as much wealth as possible from Africa.” His analysis was a gross simplification of the Indian community’s class composition. Although leaders of Indian political movements were professionals, who came from better-off families, most Indians were industrial workers and farm labourers.

Lembede’s stance towards coloureds was more flexible. He recognised that South Africa’s coloured communities were an arbitrarily defined group with many divergent attitudes and positions. Therefore, he welcomed into the African national movement coloureds who “identified themselves and assimilated into African society”, but he excluded those who classified themselves as a separate nation or as Europeans and those who shared the racist attitudes of Europeans towards black South Africans.

Lembede also argued that, in the hierarchy of segregation, Indians and coloureds benefitted from an “inequality of oppression” that accorded them slight privileges that were closed off to blacks. If Indian and coloured leaders were put in a position to advance their own political and economic interests, blacks could not realistically expect them to side with black causes.

One of the likely sources for Lembede’s attitude was the events surrounding Hertzog’s Representation of Natives Act (1936), which abolished the Cape franchise. Although coloured and Indian leaders had joined blacks in founding the All African Convention in 1935, to protest the law, a perception developed among some that the commitment of coloured and Indian political leaders had significantly diminished once the threat to their own status had eased.53

Despite Lembede’s reservations about non-European unity, he recognised that there were grievances such as voting rights on which blacks, coloured and Indian political movements could find common ground. In those cases, he urged political movements to confer with each other and arrive at joint strategies for addressing issues. Thus, after being brought onto the ANC executive in 1946, he supported moves towards closer cooperation between the ANC and the Natal and Transvaal Indian Congresses.

Another Lembede tenet was that since blacks were discriminated against because they were black, preserving their national unity overrode any class division within the black community. Therefore, the handful of blacks who had acquired wealth were not excluded from the national struggle because they had not been co-opted “into the ranks of and society of white capitalists.”

A corollary was that black workers should align their struggles with the ANC rather than pursuing an elusive class unity with workers from other racial or ethnic groups. Black workers were opposed not as workers, but as a race, by an alliance of white capitalists and a white parliament which had legislated a labour aristocracy for Europeans (and Indians and coloureds to a lesser degree) who profited from higher wages and access to better jobs.54

Lembede viewed the struggles of black workers as legitimate in their own right and a vital component of ANC activities. The “ANC without a workers’ organisation (like the ICU [Industrial and Commercial Workers’ Union]),” he conceded, “is a motionless cripple.” He backed the efforts of black workers to join trade unions and fight for higher wages and improved working conditions. However, he believed the aspirations of both black trade unions and the ANC were best served by forging a joint strategy, with trade unions dealing with economic issues and the ANC concentrating on political matters. His reference in the above quote to the ICU is significant because of the lesson he drew from the destructive rivalry between the ANC and the ICU in the 1920s – that their competition had led to the ICU’s dramatic collapse and the precipitous decline of the ANC until its revitalisation during the Second World War.55

Throughout his career, Lembede was consistently hostile to the Communist Party on religious and racial grounds. As a devout Christian, he rejected communism’s materialist ideas as alien to the African experience. He had studied some of the classic works of Marxism while writing his MA thesis and took issue with the materialist arguments that advances in modern science and knowledge were antithetical to religious beliefs. Moreover, he questioned the materialist contention that Christianity lulled Africans into political passivity. Instead, he pointed to Christian ministers who had been fixtures in the ANC’s leadership since its inception and he maintained that Christianity could be a spur to political action. Anticipating the liberation theologians, he interpreted the Christian message – especially the symbolism of Christ’s crucifixion – as a revolutionary creed capable of mobilising people to action. “The essence of Christianity,” he maintained, “is Calvary; or the Cross – the ready willingness to offer and sacrifice one’s life at the altar of one’s own convictions, for the benefit of one’s followers.”56

As an African nationalist, Lembede was alarmed by the growing prominence of communists in the ANC and other organisations. Like the ANC, the Communist Party had resurrected itself in the late 1930s and had rapidly expanded its membership by aligning itself with popular struggles in the black community, especially in the urban areas, organising trade unions, launching a national anti-pass campaign and actively involving itself in ANC affairs.

By 1945 the ANC national executive had three communists on it. That same year, Lembede and the Youth League pressed the Transvaal ANC to adopt a resolution stating that members of the ANC executives could not belong to other political organisations.57 The resolution, directed specifically at communists on the ANC national executive, was aimed at forcing them to declare their allegiance to the ANC or the Communist Party. The resolution passed thirty-one to twenty-one. But when it was considered by the national body, it was rejected. This was because Dr Xuma and other senior ANC leaders viewed the ANC as an umbrella group composed of many different constituencies and they objected to an ideological litmus test for ANC membership.58

Lembede was wary of black communists, but he was particularly suspicious of the motives of white communists assuming leadership roles in black organisations, especially trade unions, because he believed their presence undermined black leaders and fragmented black unity. In 1945, Lembede’s Transvaal Youth League turned down an invitation to affiliate with the Progressive Youth Council (linked to the Communist Party). Writing to Ruth First, the Council’s secretary, the Youth League declared that it could not subordinate itself to any other youth organisation, especially when there was “a yawning gulf between your policy or philosophic outlook and ours.”59

Lembede was certainly an uncompromising foe of the Communist Party, but was he categorically opposed to all socialist ideas? In this area, at least, his writings are open to interpretation. In one essay, he promoted a variant of African socialism, arguing that since precapitalist African societies held land communally, they were “naturally socialistic as illustrated in their social practices and customs.” His ideas were in line with other proponents of African socialism who stressed the classless harmony and unity of African societies before Europeans came on the scene. There are only a few hints in his writings of a critical assessment of capitalism and its implications for African societies. However, in one essay, he noted that since African socialism was a “legacy” to be tapped, “our task is to develop this socialism by the infusion of new and modern socialistic ideas.”60 He did not define just what these ideas were, but he was very clear that national liberation had to precede any implementation of socialist ideas, however they were defined.61

LEMBEDE’S DEATH

By 1947, having completed his education and settled into his law practice, Lembede was poised to further his professional and political ambitions. And, after many years of personal privation, he was finally in a position to look after his family’s welfare. He began sending money to his widowed mother, he paid lobola (bridewealth) for his brother Alpheus and he promised his sister Cathrene and her husband, Alpheus Makhanya, that he would bring one of their children to Johannesburg and pay for his education.

He was also re-establishing his roots in Umbumbulu. He built a four room house for himself at the Lembede homestead. He bought a Buick and instructed his family to begin building a road to his new home.62 His last letter home read:

Mame,

Sengithenge imoto enowayilensi. Ngiyofika ngayo lapho ekhaya. Makumbiwe umgwaqo uze ungene ekhaya. Ngizothumela u £20 wokumba umgwaqo.

Mother,

I have now bought a car with a wireless [radio]. I will be driving next time I come home. You must dig the road until it reaches home. I will be sending £20 for this purpose.63

And he was finalising arrangements for marriage to twenty-four-year old Cherry Mndaweni, a nurse trained at McCord Hospital in Durban. The two had met sometime in 1945 on a bus going from Ladysmith to nearby Driefontein, Mndaweni’s birthplace, where Lembede was handling a legal case. According to her, it was love at first sight; and after Lembede returned to Johannesburg, they started writing letters to each other. What made Lembede so appealing to her was his spiritual nature and his concern with family issues. She also recognised that Lembede felt comfortable with her because she had grown up in a rural area and had not taken on urban ways. Her Methodist upbringing made no difference to him, but she expected to convert to Catholicism after they married.

After finishing her training at McCord, Cherry moved to Germiston to be close to Lembede. She heard from friends that he was involved in politics, but she was still puzzled when he told her that when he was arrested one day she would have to take care of their children. She only understood the meaning of his remark as the political struggle intensified in the 1950s.

Their marriage plans moved forward in 1947 when Lembede visited her father, a clerk at the Cimmaron Jack mine in Germiston, to initiate lobola negotiations. He also delegated several friends to visit her family at Driefontein to finalise arrangements. However, he postponed his own planned visit to Driefontein in order to serve as master of ceremonies at a reception on Sunday 26 July, celebrating the awarding of a BA to his treasured friend, A P Mda.64 Mda had decided to follow in Lembede’s footsteps and pursue a career in law.

On the morning of 27 July, Lembede fell ill at his law office. Both Nelson Mandela and Walter Sisulu claimed that they were passing by his law office and noticed Lembede doubled over in pain on his couch.65 They and Lembede’s clerk called on Dr S Molema for assistance, and Lembede was taken to Coronation Hospital where he died on Wednesday, 29 July 1947, at 5:30 am. The cause of death was listed as “cardiac failure” with “intestinal obstruction” a contributing factor. Lembede’s abdominal complaints were longstanding. He had nearly died during an abdominal operation in 1940 and he’d had a similar operation in 1941.66

Lembede’s last words, taken down by his attending nurse, Rabate, were characteristically directed to his family:

All the money must be given to Nicholas, and he should use this money for going to school with. He should look well after my mother because I am taking the same path which my forefathers took. And the clothing should be given to my brother … and he should try and do all the good in order to lead the African nation. God bless you all.67

Lembede was laid to rest at Croesus cemetery on 3 August.68 His pallbearers and speakers represented a broad spectrum of black political and educational leaders: Pixley ka Seme, Elias Moretsele, Oliver Tambo, Templeton Ntwasa, Hamilton Makhanya, Yusuf Dadoo, A P Mda, Obed Mooki, Sofasonke Mpanza, Jordan Ngubane, A B Xuma, William Nkomo, Paul Mosaka and B W Vilakazi. Lembede may have been fired by an intense conviction, but he rarely allowed that to stand in the way of him developing strong friendships with his political rivals.

Following Lembede’s death, Mda took over as acting president of the Youth League until he was formally elected president in early 1948. Although he and Lembede are often paired as the Romulus and Remus of African nationalism, they did have differing visions. Mda’s views were not as “angular” as Lembede’s; he was uncomfortable with some of Lembede’s extreme stances. Although he agreed with Lembede that there was a major gulf between blacks, coloureds and Indians that could not be bridged in the short run, he had long argued that African nationalism “must not be the narrow kind, the unkind kind that discriminated against other racial groups.” He desired “a broad nationalism, imbued with the spirit of Christ’s philosophy of life and recognising the universal brotherhood of men.”69 After he became Youth League president, he elaborated on this point in a letter he wrote to Godfrey Pitje, a lecturer at Fort Hare and Mda’s successor as Youth League president:

Our Nationalism has nothing to do with Fascism and Nationalism [sic] Socialism (Hitleric version) nor with the imperialistic and neo-Fascist Nationalism of the Afrikaners (the Malanite type). Ours is the pure Nationalism of an oppressed people, seeking freedom from foreign oppression. We as African Nationalists do not hate the European – we have no racial hatred: – we only hate white oppression and white domination, and not the white people themselves! We do not hate other human beings as such – whether they are Indians, Europeans or Coloureds.70

In drafting the Youth League’s “Basic Policy”, adopted in 1948, Mda took the occasion to incorporate these views as well as distance the Youth League from some of Lembede’s radical positions. Mda inserted a section, “Two Steams of African Nationalism”, in which he rejected the one variant of African nationalism identified with

Marcus Garvey’s slogan – “Africa for the Africans”. It is based on the “Quit Africa” slogan and on the cry “Hurl the Whiteman into the sea”. This brand of African Nationalism is extreme and ultra-revolutionary.71

Because Lembede often referred to Garvey in his speeches, this was a subtle way for Mda to signal a departure from some of Lembede’s positions.

Mda also moved to strengthen the organisational network of the Youth League by travelling to all the provinces to shore up existing chapters, start new ones and cultivate established ANC leaders. By then Mda was operating from his birthplace, Herschel district, where he was teaching, so he developed his most extensive network in the Eastern Cape. The Youth League’s most energetic chapter was at Fort Hare, where there was already a group of students and staff receptive to the message of African nationalism.

In addition, Mda was a key figure in lobbying the ANC to adopt a militant programme of action. The impetus for the programme came in the aftermath of the Nationalist Party’s election victory in May 1948. At its December conference later that year, the ANC passed a resolution supporting the drafting of a programme of action to combat the new government and its avowed apartheid policies. Over the next year, Mda and other Youth Leaguers worked with senior ANC leaders to fashion a statement that committed the ANC to combat apartheid with a range of weapons: boycotts, strikes, work stoppages, civil disobedience and non-cooperation. The ANC approved the programme of action at a tumultuous conference in December 1949.

At the same time as Mda was putting the Youth League on a different footing, he also tried to memorialise Lembede’s ideas so that the nationalist position would continue to be promoted within the ANC and win new converts. Mda lectured on Lembede from time to time, but formal Lembede commemorations did not get off the ground until the mid-1950s.72 Promoting Lembede’s views became critical after 1949 as the ANC (and Youth Leaguers) began to split into two camps – those who retained their commitment to a “pure” African nationalism and those who were prepared to forge alliances with political organisations representing other racial groups and the Communist Party. The former, who called themselves the “Africanists”, were the nucleus of the faction that eventually broke away from the ANC to form the Pan Africanist Congress (PAC) in 1959. The Africanists also held Lembede memorials and used their journal, The Africanist, to reprint some of his essays as well as tributes to him and his ideas.

CONCLUSION

“No man outside the lunatic asylum can shamelessly maintain that present leaders are immortal. They must, when the hour strikes, inexorably bow down to fate and pass away, for: ‘There is no armour against fate, Death lays his icy hands on Kings.’” When Lembede penned these words in early 1947, he was not anticipating his own death seven months later, but the inevitable transfer of leadership from one generation to another. However, the fact that his life was cut short before he realised his full potential inevitably influences the way in which people view his contribution to South African political life.

A parallel that people often turn to is the Old Testament story of the Israelite search for the promised land. At a Lembede memorial held in mid-1955, a prominent African Methodist Episcopal minister, Nimrod Tantsi, compared Lembede to Moses, who “led the Israelites out of Egypt and died before reaching Canaan”, and he appealed for new Joshuas to step forward to lead Africans to their freedom.73 In 1992, when we asked A P Mda to reflect on Lembede’s contributions, he used the analogy of Moses not only to describe Lembede, but also to reinforce a point that Lembede repeatedly stressed about the importance of African leadership in the freedom struggle.

A leader of the African people must come from the Africans themselves. A true leader who’s going to lead them to their freedom … Moses belonged to the Jewish people, the Israelites … He gave them the direction. They followed that path which he gave them. In this situation the road to salvation is this one. Let’s be together, gather our forces, and then march forward and cross the Red Sea. There can be no freedom unless we cross the Red Sea. We can cross the Red Sea only if we, the Israelite leaders, lead you because we are part and parcel of you – we see the way as you see it. And we’ve got a clear vision of where we can go … Moses is part of you. He is yourselves. And he can lead you through the dangers of the Red Sea and the desert and march you to unity across the desert facing all the difficulties until we end up in the promised land.74

Lembede may not have lived to see freedom in his lifetime, but he packed a full life into the roughly four years he was active on the political scene. At his death he was emerging as a major figure in the ANC, and one wonders what his impact on the course of South African politics would have been if he had lived longer. Would the Youth League have put his name forward as their candidate to succeed Dr Xuma as ANC president in 1949? If he had become ANC president, would he have moderated his strong views on African nationalism or would he have kept African nationalist ideas to the fore in the ANC? Could he have defused the dissension in the ANC and staved off the breakaway of the PAC in the late 1950s?

Lembede was an incandescent figure whose diverse talents and educational and professional accomplishments marked him for distinction. A self-made man, he overcame his humble origins and devoted his meagre resources and his considerable energy to complete three university degrees. A gifted linguist, he communicated with ease in seven languages. A lawyer, he was the first of his contemporaries to qualify to practice. A committed Christian, he sought to translate his beliefs into political action. A political philosopher, he crafted an ideology of liberation centred around the cornerstones of African unity and a spiritual Pan-Africanism. To his age-mates he was a standard-bearer for their aspirations. And his untimely passing was deeply mourned by his friends and opponents alike. After his death, some teachers went so far as to hang his picture in their classrooms to inspire their pupils.

Lembede’s achievements as a politician were modest. Unseasoned politically when he moved to Johannesburg in 1943, he came under the tutelage of more experienced young politicians and he rapidly rose to leadership positions in the Youth League and parent ANC. Impatient, zealous and uncompromising, he was a ferocious combatant who led the Youth League charge to shake up an ANC reluctant to adopt militant tactics. These qualities were both an asset and a liability when it came to practical politics. On the one hand, he was prepared to take up causes, however formidable the odds; and he was not daunted by the prospect of taking on the power elites of both the white government and the ANC. On the other hand, his brashness and intolerance of other people’s views could lead him into blind alleys. Moreover, his attempts to pressure ANC leaders to boycott government bodies such as the NRC and expel communists from the ANC executive were easily thwarted by the ANC’s old guard.

Lembede’s temperament was more suited to the barricades than the backroom. His strength was as a polemicist, not as a tactician. Thus it is his ideas which are his primary legacy. His advocacy of an exclusive African nationalism, that Africans had to emancipate themselves psychologically and rely on their own leadership in order to challenge white domination, and that national liberation took primacy over class struggle provoked heated debate, even within Youth League circles. But his ideas struck a popular chord with many; and they fuelled debates on race, class and national identity that reverberate to this day.

Perhaps it is fitting to conclude this introduction by turning again to the words of Mda:

Anton Lembede became the most pronounced and the most forceful and uncompromising exponent of the new spirit. It is not that he was a prophet or a saint. There were other men around and behind him who were just as great. It is just that his language touched the inner chords in the hearts of the African people, and intensified the stirrings and the ferment which were already there. Anton Lembede spoke a language which reminded the people of their past greatness, and their present misery, and which opened up new boundless vistas of freedom and joy in a new democratic Africa. He gave “clear and pointed expression to the vaguely felt ideas of the age.”75

On 27 October 2002, Mandela was one of the speakers paying tribute to Lembede at the reburial of his remains at his home at Esijwini in Umbumbulu: