Читать книгу Empire’s Children: Trace Your Family History Across the World - Anton Gill - Страница 6

FOREWORD

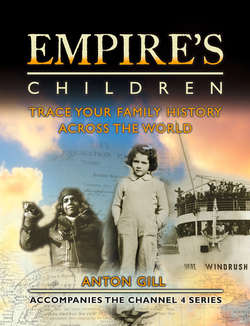

ОглавлениеThis book accompanies the Channel 4 television series of the same name produced by Wall-to-Wall. It is designed to fill in the background of the stories (which are included here) told in the six television episodes, by describing briefly the rise and fall of the British Empire, but concentrating on its last days – those following the end of the Second World War – together with the impact of emigration to Britain from her former colonies, the effect of Britain on the immigrants and their effect on her, and the gradual and still incomplete journey towards integration and harmony. Recent events, including highly destructive and successful terrorism, and ill-advised and equally violent reactions to it, have interrupted the process. One can only hope that it will resume, but current damage will take a generation or two to repair.

Any opinions expressed in these pages which are not otherwise acknowledged are my own, and should not be associated with any of the individuals or organizations mentioned above, or elsewhere in the Acknowledgements.

British influence as a world power began to develop towards the end of the sixteenth century, grew to full flower in the nineteenth, and only began its long decline after the First World War, a decline which accelerated during the second half of the twentieth century.

During the entire period a number of things changed, among which place names and the British currency system are the most obviously striking. As names and references to the old British, non-decimal currency occur from time to time in the narrative which follows, it is good to be aware of them.

On 21 February 1971, the United Kingdom adopted a decimal system of currency similar to those already in use in most countries. Everyone born in the UK from the late 1960s onwards will be aware that 100 pence equals £1. It was not always thus. Before 1971, a system of pounds, shillings and pence existed. According to that system, which had been in use for centuries, there were 240 pennies (or pence) in a pound. Twelve pennies made up a shilling, and there were twenty of those in a pound. The pound was designated by the familiar £ symbol (denoting libra, the Latin for ‘pound’), the shilling by ‘s.’, and the penny by ‘d.’ (the first letter of denarius, the Latin word for a small Roman silver coin). Sums of money were expressed thus: the modern £1.25p would have been £1. 5s. Od., 25p would have been 5s. Od. or 5/-.

Apart from the shilling and the penny there were several other coins, in use at various periods, each representing other subdivisions of the pound. Those that survived to 1971 were the half-crown, the florin (2s. or 10p), the sixpenny and threepenny bits, and the halfpenny.

There is one other measurement of money that the reader should be aware of: the guinea. The guinea ceased to exist as a coin long ago, and largely disappeared as a recognized unit of payment before the watershed of 1971. Before that it was used latterly as an expression of payment of professional fees. The BBC paid contributors in guineas, and the fees of medical specialists and lawyers were demanded in them. The guinea was worth £1.05p, or £1. 1s. Od.

The origin of the guinea is interesting and has a direct connection with the early period of British dominion overseas. The coin was first struck in 1663, ‘in the name and for the use of the Company of Royal Adventurers Trading to Africa’. It was intended for the Guinea trade and was originally made of gold from Guinea, the name given to a small portion of the west coast of Africa. The splendidly named company, headed by Charles II’s brother James, Duke of York (later James II), dealt mainly in slaves. It had its ups and downs, but traded in slaves until 1731, when it switched to ivory and gold. It provided gold to the Royal Mint from 1668 to 1722. The slave trade continued to flourish until its abolition (by Britain at least) in 1807.

Place names and names of definition present a slightly more complicated problem. Names of definition change with assumptions of political correctness. Once, the term ‘Black’ was generally thought offensive, but ‘Negro’ was not, at least not to ‘white’ people. Now the reverse is true. Appalling as it seems now, people in the 1950s and earlier would quite innocently call a pet black Labrador ‘Nigger’ or a black cat ‘Sooty’ or ‘Blackie’. Most of us have come a long way towards greater integration and understanding since then, but at some cost; and sensibilities must be treated with respect as a result.

Care has to be taken with other general definitions. It is okay to call ‘Europeans’ that as a catch-all, but we are well aware that Europe is made up of a number of very different nations, languages, religious sects and cultures. That has not always been true of Europeans’ perception of other parts of the world. While the term ‘Asians’ appeared soon after the end of the Second World War as a useful umbrella-term for those peoples inhabiting what had been British India – that is to say, the Burmese, the modern Pakistanis, the modern Bangladeshis, the Sri Lankans and the Indians – nowadays the slightly more defining term South Asians appears to be preferred. The same sort of issue applies to the question of whether to use ‘West Indian’ or ‘Afro-Caribbean’ as a denomination of convenience when one cannot specify a particular island or island nation.

Such applications change with fashion and time. I have opted for those which, after consultation, seem most acceptable at the time of writing to those to whom they are applied. If any offence is caused by any reference in the pages which follow I apologize, for this is purely unintentional.

Two earlier usages which occur less frequently these days but will be found in older books, articles and so on are ‘Anglo-Indian’ and ‘Eurasian’. The former can mean either a person born in India of mixed Anglo-South Asian parentage, or a native British white (Caucasian) person who had spent a considerable time in India, usually in government or military service, possibly born there, and who would have considered India, not Great Britain, his or her principal home. The term ‘Eurasian’ denotes only the former category, that is, a person born of Caucasian-South Asian parents. I have decided in this book to use Eurasian for a person of mixed race, and Anglo-Indian for the British Indian long-termers. But be aware that the latter expression will sometimes be found elsewhere denoting the former.

Place names can change with the political climate. Look, for example, at the progression over the last century or so from St Petersburg to Petrograd, to Leningrad, and now back to St Petersburg. If you look at an atlas published in 1937 and at an atlas published in 2007 you will see a large number of name and even frontier changes, in the Russian landmass, in what was British India, and in Africa. Only British India and Africa concern us here, and almost all the dramatic changes of name there had taken place by 1980, when the last British colony, Rhodesia (earlier, Southern Rhodesia), became Zimbabwe.

One or two countries have changed their names twice or more in the past half-century. For example, the Belgian Congo gained independence in 1960 and became the Republic of the Congo, a name it shared with a neighbouring state, the former French colony of Congo. In 1966 the former Belgian territory was renamed the Democratic Republic of the Congo. After a period of war and unrest one political leader, General Mobutu, became dominant, and under him the country became the Republic of Zaire in 1971. (The name ‘Zaire’ derives ultimately from Nzere, a local name for the River Congo.) But, as was the case in so many newly independent African states, repression and unrest continued, and Zaire’s future was compromised in the mid-1990s by involvement in the war in neighbouring Rwanda. This led to the fall of Mobutu and the reversion under new leadership, in 1997, of Zaire to its earlier name of the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

Many other colonies – British and otherwise – in Africa changed their names on independence, often reverting to pre-colonial or ancestral names. Thus the first to attain autonomy, the Gold Coast, became Ghana. Tanganyika and Zanzibar merged as Tanzania, Nyasaland became Malawi, Northern Rhodesia became Zambia, Bechuanaland became Botswana, South-West Africa became Namibia (as late as 1990), and so on.

The situation in what had been known as British India (prior to the end of the Second World War) changed with the end of British rule there and the political partition of the subcontinent in 1947. The original divisions were India, East and West Pakistan, Burma and Ceylon, along with a couple of the former Independent States (separate countries within the Raj but more or less in thrall to it) which had refused to become subsumed within either the new Hindu or Pakistani divisions. One of these, Kashmir, is still being fought over today. Ceylon, independent of Britain since 1948, changed its name to Sri Lanka (meaning ‘Venerable Lanka’) following a socialist revolution in 1972. A year earlier, East Pakistan (itself formerly Bengal) broke away from West Pakistan (now Pakistan (‘Land of the Pure’) and became the independent state of Bangladesh (‘Land of the Bangla Speakers’). Burma, which became fully independent of Great Britain in 1948, changed its name to Myanmar (its pre-colonial name) in 1989, and that of its capital from the westernized ‘Rangoon’ to ‘Yangon’.

I have decided to follow my own judgement in what place names to use in the pages which follow. This means on the whole that for African and South Asian countries I will use their current names, with their former colonial names afterwards in brackets where appropriate. However, in some cases I have stuck to older usages as still being more familiar to most readers. Thus, for example, although I have preferred Beijing to Peking, I have used Madras rather than Chennai, Bombay rather than Mumbai, and Burma and Rangoon rather than Myanmar and Yangon. I have also used Mecca rather than Makkah, Cawnpore rather than Kanpur, Calcutta rather than Kolkata, and Mafeking rather than Makifeng. Where any elucidation or explanation is necessary, I have given it immediately in parentheses, but in the course of telling a complex story I apologize here and now for any inconsistencies.

Where it applies (England was a separate country from Scotland until 1707 and Scotland played only a tiny part in an independent colonization process before then) I have also decided to use ‘Great Britain’ or ‘Britain’ rather than ‘the United Kingdom’ because to me the former names reflect the period better than the latter, and tie in more euphoniously with what lies at the centre of this exploration of the British Empire.