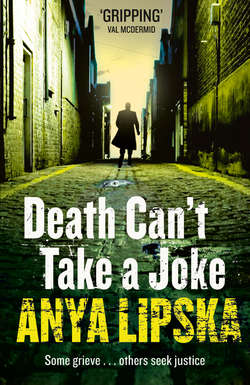

Читать книгу Death Can’t Take a Joke - Anya Lipska, Anya Lipska - Страница 15

Eleven

ОглавлениеThe wooden shutter gave a single mournful squeak as it was pulled back from the wire grille.

‘I present myself before the Holy Confession, for I have offended God,’ murmured Janusz.

‘Have I heard your confession before, my son?’ asked the priest.

Janusz peered through the grille for a beat, before realising that Father Pietruski was winding him up.

‘It’s been –’ a surreptitious count of his fingers ‘– a long time since my last confession.’

‘I was thinking you must have run away with the gypsies,’ said Pietruski, bone-dry. ‘Or perhaps even gone home to honour your marriage vows to that wife of yours, not to mention your parental duties.’

Janusz shifted in his seat. Pietruski had been his priest for more than twenty years now, and it seemed he would always have this ability to make him feel like a wayward teenager.

‘You know that Marta and I got divorced,’ he said reasonably. The priest started to speak, but Janusz broke in. ‘Yes, Father, I know the Church doesn’t recognise divorce, but that’s the reality in our hearts.’

Janusz had been just nineteen when he and Marta had wed. The ceremony took place in a fog of grief and wodka, just weeks after the death of his girlfriend Iza, and the marriage had proved to be a cataclysmic mistake. It had, however, produced one outcome for which he felt not a trace of regret. Years after they’d split up, during a single, ill-advised, night of reunion, they had created a child together.

Things had improved between Janusz and his ex-wife over the last year or so, and although he liked to think the thaw in their relations was due to his efforts to be a better father to their fourteen-year-old son Bobek, he half suspected that it had more to do with Marta’s new boyfriend, six or seven years her junior, who she’d met at art evening classes. On the phone to Lublin, where she and the boy now lived, he had heard her laugh in a way she hadn’t done for years – and was glad of her newfound happiness.

‘As for Bobek, I’m a passably good father these days,’ he continued. ‘I flew over to see him only last month and we speak on the phone several times a week.’

‘I see,’ said the priest. ‘So, aside from your personal decision to ignore the unbreakable sacrament of your marriage, are there any other sins you wish to report?’

Janusz thought for a moment. ‘Coveting another man’s wife,’ he said, visualising Kasia, blonde hair tumbling over naked shoulders.

‘Only coveting?’

‘It’s all I’ve had to make do with in the last few weeks.’

‘Anything else?’ Pietruski’s tone had become even more acid.

Janusz hesitated. ‘Murderous impulses,’ he said, his voice a low rumble.

‘Against whom?’

‘Against the skurwiele who killed a friend of mine, Jim Fulford.’

That made Father Pietruski pause and squint through the grille. ‘What a dreadful thing. I will pray for you – and your friend, God rest his soul.’

Both men crossed themselves. ‘But you must leave it to the authorities to pursue the wrongdoers,’ said the priest. ‘You are not God: it is not given to you to look into a man’s soul, to decide how to punish the guilty.’

Janusz’s grunt was non-committal.

‘We’ve spoken before about this anger of yours, my son. And how in the end these negative emotions can hurt only yourself.’

‘Yes, Father,’ said Janusz. But he was irritated by his confessor’s recent tendency to couch things this way. He came here for the implacable wisdom of a 2000-year-old Church, not a serving of New Age psychobabble.

‘Is that everything?’ asked Pietruski.

Janusz opened his mouth, on the verge of admitting his plans to get inside Scarface’s apartment later that day, before remembering that it wasn’t the done thing to confess sins in advance. A wise man had once said: Better to beg for forgiveness than ask for permission.

‘Yes, Father, that’s it.’

Janusz lingered in St Stanislaus longer than was strictly necessary even to perform the elaborate menu of penances Father Pietruski had seen fit to give him. Wrapped in its cavernous quiet amid the smell of snuffed candles and incense, he allowed himself a few moments to grieve for Jim, but resisted the urge to pray for him. That might undermine his resolve. Vengeance first, prayers later, he told himself.

Finding out Barbu Romescu’s address from Wiktor, his DVLA contact, had been a hundred quid well spent, but the next step – investigating his possible connection to Jim’s murder – would be harder to pull off. Janusz had spent several hours on his laptop and printer the previous night in preparation for the afternoon’s work, which he’d planned to coincide with the Romanian’s second weekly meeting at the Turkish shisha café.

By the time he walked into Romescu’s apartment block, twin needles of blue glass overlooking the old Millwall dock, not far from Canary Wharf, he’d completely immersed himself in his cover story.

Reaching inside his overalls, he pulled out a piece of paper and handed it to the skinny guy on reception, who, in a couple of years’ time, might be old enough to start shaving.

‘Tower Management. Leaking air-conditioning unit in apartment 117,’ he said. How had he ever managed to do his job in the days before the internet, he wondered. Back then, even discovering the name of the management company would have taken hours of phone bashing, and as for photoshopping its logo into a fictional work docket? The idea would have been the stuff of science fiction.

‘I’m really sorry.’ The guy handed the document back to him with an uncertain shrug.

Don’t tell me they’ve changed companies or something, thought Janusz.

‘The concierge is off sick,’ he went on. ‘I’m just a temp from the agency, filling in.’

Alleluja!

Scowling, Janusz looked at his watch. ‘Well, I’ve got four more jobs after this one so I haven’t got time to muck around.’

‘I’ll see if the residents are at home.’ The kid punched out a number on the phone.

With every passing second that the phone went unanswered, Janusz allowed himself to relax a little. He made a production of shifting his half-empty toolbox from one hand to the other, as though it weighed a ton.

Finally, the kid hung up. ‘They’re not in,’ he admitted, gazing up at Janusz like a baby rabbit encountering a bear.

‘Look, here’s the drill,’ sighed Janusz. ‘You take me up to 117 and let me in, I do the job, you sign the docket afterwards to say it’s done.’

The kid was already shaking his head. ‘I can’t. The agency told me I mustn’t leave reception under any circumstances.’

Janusz checked his watch again and raised an eyebrow. ‘Well, I’ll leave you to explain that to the people in 117.’ He started to walk away. ‘Tell them to phone the office to rebook an engineer.’

He hadn’t even reached the door when the kid called him back. ‘What about if I give you the master key and you go up on your own?’

Janusz felt a pang of guilt at the kid’s anxious expression. ‘I don’t know … I’d like to help you out, but strictly speaking, it’s against company regulations.’

‘Who would know, if neither of us says anything?’

Janusz took a moment to examine the toe of his workboot. ‘Go on then,’ he said, finally. ‘But keep it to yourself, or we can both kiss goodbye to our jobs.’

Barbu Romescu’s apartment was located on the 11th floor and his front door, like all the rest, was fitted with a state-of-the-art electronic lock. Janusz slipped the master card into the slot. A green light winked at him. As he pushed the door open, he grinned to himself. The first rule of security: humans were always the weakest link.

When he saw the apartment’s open plan living area, Janusz gave a low whistle. Whatever the nature of Romescu’s mysterious ‘business interests’, they apparently paid very handsome returns. Light coming through the floor-to-ceiling plate glass windows flooded the enormous room, bouncing off the highly polished wooden floor, some sort of golden-coloured hardwood. To his right stood a gleaming, minimalist kitchen. He looked it over with an ex-builder’s eye, noting the way in which the designer, not satisfied with hiding every appliance from view, had even eliminated door handles from the black acrylic units.

Testing how they worked – the merest touch on the surface caused it to swing open silently – Janusz chanced upon the fridge. He surveyed its contents with an expression of mystified disgust. Having worked alongside Romanians on building sites he knew they could put away pork, dumplings and a good feed of beer with as much gusto as any God-fearing Pole, yet all Romescu had in his fridge was vegan yoghurt, a tray of alfalfa sprouts, a carton of egg white and some goji juice.

Padding around the living area, Janusz had to admit that it wasn’t half bad for a dodgy Romanian ‘businessman’. The furniture looked expensive yet elegant, and the artworks on the walls were the kind you might find in an upmarket yoga studio. The largest, at around three metres across, was a rather good hyperrealist painting of a butterfly in flight, sunlight making its pale blue wings translucent.