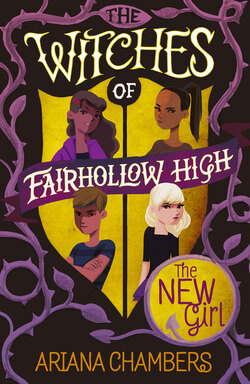

Читать книгу The New Girl - Ariana Chambers - Страница 5

Оглавление

One of my favourite feel-good film scenes of all time is from a movie called Winter Vacation. In it, the main character, Lola, has just arrived home from college for Christmas. She’s trudging through the airport feeling all gloomy because she thinks her boyfriend, Josh, is going to be away for the holidays visiting his dad. But as she walks into Arrivals she sees Josh waiting for her with a big soppy grin on his face. He’s holding one of those little cardboard signs with her name on it and I love you, Peanut! written underneath (‘Peanut’ is his nickname for her, but that’s a whole other story). The second Lola sees him, she flings herself over the barrier and into his arms. Every time my best friend Ellie and I watch that scene – even after about five hundred viewings – we tear up. Every time, without fail.

As I walk into the Arrivals hall of Newbridge Airport, trying to keep my trolley wheels straight and my guitar from sliding off my tower of cases, I can’t help scanning the line of people at the barrier hopefully. Even though I know Aunt Clara isn’t able to meet me because she has to be at her shop for a delivery, and even though there’s absolutely no one else to come and meet me, because:

a) I don’t have a boyfriend like Josh,

b) I don’t have a boyfriend, period,

c) I don’t know anyone other than Aunt Clara in this place, my eyes still search for a piece of cardboard with my name. But there’s only one person holding a sign, a chubby man with a red face, wearing a too-tight suit. His sign says MR BAILEY. Definitely not Nessa Reid. Definitely not me. I sigh and push my trolley past the line of people, trying to look all cool and nonchalant, like I don’t care that I’ve been sent to this stupid place, in the middle of nowhere, with no friends and no one to even come and meet me at the airport. As my guitar almost slides off the trolley again I think of my dad and feel a stab of anger. He gave me the guitar as a going-away gift – like that’s going to make up for the fact that he deserted me to go and work in Dubai, in the Middle East. At least I have something I can write angry songs about bad parents on, I guess.

I look around the Arrivals hall. Dad told me that the taxi rank would be on my right. I didn’t realise that he’d meant literally. The airport is so tiny I can actually see the taxis lined up on the other side of the glass wall. I push my trolley over to the doors. As they slide apart I’m hit by a sharp blast of cold air. When I left London the weather was bright and sunny, but here in Scotland the December sky is a dull, heavy white, like a thick layer of cotton wool. My trolley clatters on the paving stones as I walk over to the first cab in the line. I fumble in my pocket for the piece of paper Dad gave me with Aunt Clara’s address on it, even though I’ve studied it so many times during the flight that I know it by heart. I’ve got a horrible anxious feeling in my stomach.

‘Please can you take me to Paper Soul on Fairhollow High Street?’ I say to the driver as he gets out of his taxi and opens the boot. He has short silver-grey hair and a slightly flattened nose, like he might have broken it once in a fight.

‘Paper what?’ he says, picking up one of my cases.

‘Paper Soul. It’s a bookshop – and café.’ This is the one good thing about being sent to stay with Aunt Clara – I’ll be living above a café and a bookshop, two of my favourite things in one building. ‘It’s next to the chemist’s,’ I add, looking back at Dad’s directions.

‘Ah,’ the driver says knowingly. ‘That place.’

He doesn’t exactly sound impressed. I get into the back of the cab and try not to wonder why. As I stuff the piece of paper back into my pocket my fingers brush against my mum’s locket. Instantly, I feel better.

My mum passed away when I was very young – not long after I had been sick in hospital myself as a baby. I don’t really remember her, and Dad doesn’t talk about her very much, but last night when I was packing to leave he gave me this locket. ‘It was hers, and she would have wanted you to have it,’ he said gruffly. It’s beautiful, small and silver with a five-pointed star delicately engraved on the front, and I love the way it feels in my hand.

As the driver pulls away from the airport, I close my eyes and play the Worse Off Than You game. This is a game I invented during a particularly grim Science test involving the Periodic Table. The idea is that whenever you’re feeling really stressed about something, you just have to think of a much worse scenario and it will instantly make your own problem feel smaller. I imagine a girl my age, thirteen, stranded in the middle of the Sahara Desert. She hasn’t had anything to drink for days and a herd of snorting camels are about to stampede her. I open my eyes and look out of the window. We’re driving along a narrow country lane, surrounded by bare, stubbly fields. It looks pretty bleak, but at least there are no stampeding camels and I have a bottle of water in my bag. I take it out and have a sip. There really are a lot of people a lot worse off than me. This really isn’t the end of the world . . . it just feels like it.

Eventually, we leave the twisty turny lanes and pull on to a slightly wider road. We’re still surrounded by fields, but every so often a car passes us so I guess we must be getting closer to Fairhollow. I press my face up against the cold window. The sky is now darkening from white to grey, as if someone’s shading it in with a pencil. I feel a flutter of anxiety in the pit of my stomach. I haven’t seen Aunt Clara since she last came to visit me and Dad, when I was about six. I wonder if she’s changed much. I have a memory of her from that day, filed away in my head like an old photo. She’s standing in the back garden, staring blankly ahead, her long golden hair blowing in the wind. I think she and Dad had just had an argument. I can remember Dad marching into the house and the back door slamming. I also remember Aunt Clara hugging me when she was leaving. She smelt like rose petals. I start to relax a bit. Hopefully it will be nice living with Mum’s sister – and hopefully I can find out more about Mum.

The road starts curving up a really steep hill.

‘Soon be there,’ the driver says, looking at me in the rear-view mirror.

I nod back at him. ‘Thank you.’

Finally, we reach the top of the hill and there’s something other than fields to look at. A town is spread out far below us, in the base of a huge valley, surrounded on either side by thick ridges of woodland.

‘You from Fairhollow?’ the driver asks as the road starts cutting down through the trees.

I shake my head. ‘No. My mum is – was. I’m going to stay with my aunt.’

‘Interesting place,’ the driver says. But again, something about the way he says it doesn’t make it sound like a good thing.

‘What do you mean?’

‘You’ll see.’ As our eyes meet in the rear-view mirror, the anxious feeling returns to the pit of my stomach. I look out of the window. The tree branches are spread above us like a canopy and pale wintery light is filtering through them. It would have looked really pretty if the sun was shining. Finally, we emerge from the woods and I see a sign by the road saying WELCOME TO FAIRHOLLOW. Someone has scrawled something underneath in red but it’s too small for me to make out what.

The road we’re on leads directly to Fairhollow High Street. We go past a row of tall grand houses. They all look a bit faded and worn, though, with peeling paintwork and grimy windows. When the driver stops at a crossroads and a group of kids about my age cross in front of us my skin prickles with fear. Tomorrow, I’ll be joining my new school. I think of my best friend, Ellie, again and I feel a pang of sorrow. Ellie and I have gone to school together for what feels like forever. I can’t imagine lessons without her. It feels all wrong. I watch the kids as they head into a café called The Cup and Saucer. They’re all laughing and joking, deep in conversation. The traffic light turns green and the driver heads on down the High Street. It all looks really olde worlde and there’s no sign of any kind of supermarket. Then I spot Paper Soul at the very end of the road. It’s a tall thin building, three storeys high. Its sign is hand-painted, red lettering on a black background with a silver crescent moon in the corner. As the driver pulls up, I see a dimlylit display of books in the window.

‘All right, love?’ The driver looks over his shoulder at me.

I nod. But I feel anything but as I follow him out of the taxi. My head is stuffed full of what ifs. What if Aunt Clara and I don’t get along? What if she doesn’t really want me here? What if I hate it here? What if I don’t make any new friends?

The driver brings me my cases and I pay him with some of the money Dad gave me this morning.

I wait until he’s driven off and then I open the door to the shop. A bell above me jangles loudly, making me jump.

‘Hello,’ I say, nervously, as I step inside.

The shop smells of a weird mixture of incense and baking bread. As my eyes adjust to the darkness, I see tall alcoves lined with books on either side of me. Just in front of me, there’s a stand-alone display. I do a quick scan of the titles: Ghost Hunting for Dummies, Haunted Castles, Spirits and Spectres. I frown. Why would Aunt Clara have a display of books like that? My dad’s always said that supernatural stuff should be renamed super-stupid. He reckons that people only go on about ghosts and stuff nowadays to keep trick-or-treaters in sweets. Maybe Aunt Clara got the books in for some kind of Halloween promotion and hasn’t bothered taking them down yet. I scan the shop for a teen fiction section. But everywhere I look seems to be the same kind of stuff: Astrology, Spirituality, New Age, Healing. I feel a pang of disappointment. In my mind, I’d been picturing Aunt Clara’s shop as cosy and bright, filled with other teenagers chatting about books, but this is more like a really old library. Hopefully the café part will be a bit more cheerful.

I drag my cases past two more alcoves of books and the shop opens out into the café area. It’s completely deserted. There’s a counter running along the back, with a handful of round tables arranged in front of it. At the centre of each table there are thick, red candles with trails of wax run down their sides like bulging veins.

‘Aunt Clara!’ I call, really loud now. This place is starting to give me the creeps.

I hear a door slamming out back and the sound of footsteps. Then Aunt Clara appears in the doorway behind the counter. At least, I think it must be Aunt Clara – she looks totally different to how I remember her. Her long hair has been cut into a sharp bob that just skims her shoulders and it’s been dyed flame red. She’s wearing a long black dress, and the only splash of colour on her – apart from her hair – is the bright turquoise pendant she’s wearing on a long silver chain around her neck. She looks at me and gasps.

‘I’m Nessa,’ I say. My face instantly starts to burn. I have this really annoying habit of flushing bright red any time I’m nervous.

‘Yes, I know,’ Aunt Clara says, still staring at me. ‘You look so . . .’

She comes out from behind the counter and stands right in front of me. Her icy blue eyes are ringed with black eyeliner, making them look even more striking. She reaches out and takes hold of a lock of my hair. It probably is too long – it’s almost down to my elbows now. I know from the one photo Dad gave me that I look like my mum. I get the same anxious bubbling in my stomach that I got in the cab, but way stronger this time, so strong it’s making my legs go weak.

‘You look so much like Celeste,’ Aunt Clara whispers. But she doesn’t smile.

‘Can I – is it OK if I sit down?’ I gesture at one of the tables.

‘Of course. Yes. Do. You must be tired. And hungry. Are you hungry? I’ll get you something to eat.’ Aunt Clara seems really nervous too, and it makes me realise what a big deal this must be for her. She never got married or had any children, and now she’s been lumbered with a thirteen-year-old she barely knows – one who looks exactly like her dead sister.

Even though I’m not hungry, I nod, not wanting to upset her. She hurries off behind the counter and returns with a glass of really bright orange juice and a chocolate brownie. I smile in relief. If there’s one thing guaranteed to make me feel better it’s a chocolate brownie. I take a huge bite. Ugh! It takes all of my willpower not to spit it straight out again. It tastes vile.

‘Ah, you’re obviously not used to beetroot brownies,’ Aunt Clara says.

I stare up at her. ‘Beetroot?’ Who puts beetroot in a brownie?!

‘Yes. It’s a vegan recipe. This is a vegan café,’ Aunt Clara explains, pointing to a blackboard on the wall with Soup of the Day: Pumpkin Seed and Potato written on it in chalk.

I manage to swallow the mouthful of brownie without retching and reach for my orange juice to help get rid of the taste. But that’s even more disgusting.

‘It’s carrot juice,’ Aunt Clara says.

‘It’s lovely,’ I lie.

Aunt Clara raises her eyebrows. ‘Don’t worry, lots of people hate vegan food at first but you’ll soon get used to it.’

I frown. She’s caught me out.

Aunt Clara shifts awkwardly from one foot to the other. She has silver rings on every one of her fingers, including her thumbs. My eyes are drawn to one on her little finger, a cat’s head with emerald eyes. ‘Once you get used to organic, sugar-free foods, you’ll never want to eat anything else,’ she says. ‘It’s so full of flavour.’

I take another bite of my beetroot brownie and force myself to swallow. Aunt Clara looks down at me like she might be about to say something but she stays silent. I smile at her. It makes my face ache.

One thing’s for sure, if I’m going to stay here without hurting Aunt Clara’s feelings, I’m going to have to work a whole lot harder on my lying skills.