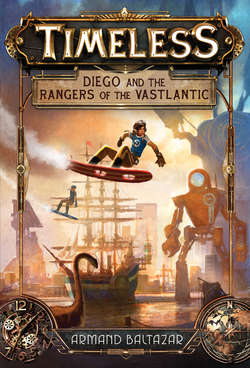

Читать книгу Diego and the Rangers of the Vastlantic - Armand Baltazar, Armand Baltazar - Страница 13

ОглавлениеCHAPTER THREE

A Workshop of Wonders

Diego and Santiago rode the elevator down to the workshop. The elevator clacked and shimmied, its gears grinding. Like so many things, it had once run on electricity, but the Time Collision had made the earth’s magnetic field violently unstable. As a result, virtually nothing electric worked. Some simple devices worked with the help of Elder fuses but only in limited capacity and only for short amounts of time. Limited use of old-fashioned telegraph devices was the only form of long-distance communication. Anything that had used circuit boards needed to be resurrected using steam, hydraulics, limited diesel, and manual labor. The work that Santiago had pioneered, mixing Steam-Time and Mid-Time technologies, had been the key to rebuilding the world safely. He had replaced this elevator’s smooth plastic buttons with brass ones that triggered little pistons, which in turn connected to gear works. The elevator lowered with a rhythmic pumping of steam compressors. Like most things in the city, it smelled of machine oil.

The elevator lurched and clanged to a stop, the doors grinding open.

As they did, Diego felt an odd sensation in his head. The world swam slightly, and there was a faint ringing in his ears. He put his hand against the wall to steady himself.

Santiago stepped out into the hall and glanced back at Diego.

“Diego, are you okay?”

“Yeah, I just . . . I’m fine,” Diego said, following him out. He took a deep breath and felt normal again, but when he looked up, Santiago was still gazing at him oddly.

“Dad, what?”

Santiago shook his head. “You just looked green for a second. You sure you’re all right? It’s going to be a big job today. I’ll need your best effort.”

“It’s just driving a loader,” Diego said, walking beside Dad. “And I’m sure their steam converter is nowhere near as sophisticated as yours.”

“No,” Santiago agreed. “But its designer, George Emerson, is a tough nut to crack. Don’t take his attitude personally. He’s been here six months already, working on the retrofit, and the encounters I’ve had with him have been . . . less than pleasant. His son Georgie has been helping too, though, and he’s much nicer. Maybe you two will have something in common.”

“Maybe,” Diego said.

They walked down a high-ceilinged hall, their footsteps echoing on the long, warped boards.

“Hey, have you thought any more about what you want to do this summer?” Santiago asked.

“Nah,” Diego said. “I’m not sure yet.”

“Time’s getting short,” Dad said. “If you want to fly and service the planes with your mother at the air base, I’ll need to find an apprentice for the shop. And that will be hard, since I already have the best young engineer in New Chicago.”

Diego knew that if he looked up, he’d find Dad smiling proudly, so he kept his eyes on the floor. “I like working in the shop, Dad. It’s just . . .”

Santiago sighed. “I know. You love to fly. Besides, Mom should get a summer with you for once.” Santiago patted Diego’s shoulder. “She’s jealous of all the time we get together.”

“I could still come by in the evenings,” Diego said. “I mean, to check in on the robots and stuff.”

“I’m sure that won’t be a problem. I’d be glad for it. Whoever I find will no doubt need a lot of training.”

“Well, yeah, but then you’ll have someone around who can really help out, long term.”

Santiago shrugged. “Someone who will need things explained three times when you barely needed once.”

“That’s not true,” Diego said. “I wrecked that plasma torch last month, even though you showed me how to use it.”

“That plasma torch would be hard for even my most experienced men to operate.”

“Yeah, but . . .”

Santiago stopped and patted Diego’s shoulder. “It’s all right. I hear you. Flying sounds more exciting.”

Diego wasn’t sure that was what he was saying at all. And he hated this feeling that he was letting his father down, but also that Dad kept assuming Diego was a genius builder like he was. Actually, there was little chance he’d ever be the pilot that his mother was either. Both his parents cast tall shadows.

“You know working with Search and Rescue will be a lot more swabbing decks and windshields than flying patrols or performing rescues,” Dad said.

“I know.” Diego understood that what he most often pictured—spotting Aeternum scout ships, arcing through the air with his cannon rifles firing—was unrealistic for his summer.

A shrill bark echoed in the hallway.

“Hey, Daphne.” Diego bent, and the little orange-and-white Shiba Inu nearly jumped on his face. “Whoa, girl.” Diego wrestled the dog down and gave her a quick, furious scratch. “Nice to see you, too.”

He stopped at a large metal door on runners and twisted the big dials on its lock. The door hissed and began to grind open.

“Over here,” Santiago said. He stood by a large iron workbench, its faded red paint chipped and worn away. The sunlight bathed a black tarp covering something on the table.

“Now,” Santiago said, grinning like a kid. “Back to your birthday . . .” He whipped off the tarp.

There it was: a gravity board, the magnet-bottom boots, steam pack, and gloves beside it.

“Awesome,” Diego breathed. He gazed at the polished surface, at the fans and machinery. The design was so cool. Diego could barely keep himself from grabbing it and jumping headlong out the window.

“Oh,” he said. “Hey, you weren’t kidding . . . it’s not finished.”

“What do you mean, it’s nearly there . . . isn’t it?” Santiago asked, eyeing him.

Diego pointed to the board. “Well, the rear thruster and the mercury accelerator haven’t been installed yet.” It seemed obvious to Diego, but that was strange; he’d never really studied exactly how these boards worked. He’d been too concerned with how to fly them.

“I was going to finish it today and give it to you tonight,” Santiago said, stepping over to a bench by the wall. He returned with an armful of parts. “But maybe you should try to finish it yourself.” He placed the parts on the table.

“Me?” Diego said. “But I’ve never worked on one of these.”

“I think it will be different today.”

“Dad—”

“Diego. Try.” Santiago’s hand fell on his shoulder. “I want you to place your hands on the engine components and close your eyes.”

Diego glanced at his dad.

Santiago nodded at the parts. “I’m serious. Go ahead.”

Diego shrugged. “Okay . . . but this would probably go a lot faster if you did it.” He placed his hands over the cool metal pieces and closed his eyes.

“Now, try to see how the engine should be put together in your mind.”

“But I have no idea how—”

“Just try.”

Diego almost pointed out that birthday presents were a lot less fun when they were tests. Also, what if he couldn’t do it? He wanted to fly this thing today!

But even as he was wondering this, a strange thing began to happen in Diego’s mind. He saw flashes . . . images of the parts. Not just the parts, but how they fit together. It happened in bursts of white light against darkness. He focused on two pieces and saw them connect. Two more, now three. And not only that, he sensed their relationships, how the different pieces functioned together, how each gear, each material had a purpose.

Distantly, he felt his muscles working, his hands and arms moving, following the images in his mind. He lined up pieces, grabbed a screwdriver from the far end of the table, made a connection. . . .

It was like watching a movie about how to put the parts together, except that movie was playing inside his mind, almost like some part of him already knew. But how do I know this? he wondered.

The thought broke his concentration, and the images sank back into the darkness.

“Ow!” Diego felt a stinging sensation as he opened his eyes. He’d stabbed his thumb with the screwdriver. He hadn’t drawn blood, but there was a red indentation.

“What just happened?” Diego asked, looking up at Santiago. “I saw something, but I lost it.”

“Relax,” Santiago said, his voice nearly a whisper. “Concentrate on the pieces and try again. Clear your mind and think only about the build, and nothing else.”

Diego closed his eyes and focused harder. The flashes returned, showing him more. His hands moved faster, his brow starting to sweat. He finished the accelerator and moved to the motor, calibrated it, and finished the assembly.

I can’t believe this is happening, he thought. What is making this happen—

Just that simple thought seemed to snuff out the images again. Diego took a deep breath and concentrated again, but the images didn’t return. Come on. He tried to think of nothing else, to clear his mind and focus, but there were only distant impressions in the dark, like shapes through a fog.

Diego sighed and opened his eyes. “I lost it,” he said. The board was nearly complete. He stepped away from the bench, breathing hard. His brain felt stretched, his head tingly. He eyed the board. “Dad, what was that?”

“I’ll show you.” Santiago shut his eyes and reached to the parts. His fingers traced over the last small pieces, then fit them together to make a compression valve, which he placed in the motor. He flipped a switch, and the mercury accelerator purred to life. The board rose in front of them, hovering a foot off the table.

“How did you do that?”

“We did it,” Santiago said, “by seeing it and only it. There can be no other thoughts or feelings. Your total focus must be on the thing that you make.”

“That doesn’t make sense,” Diego said, except it had made sense as it had been happening. “How is that possible?”

“First things first,” Santiago said. “Tell me this: Did you notice anything different about that engine as you were working?”

Diego was surprised to realize that he had. “You replaced the titanium mounts with destabilized aluminum alloy.”

“And why would I have done that?”

“Um . . . because it is lighter and more powerful,” Diego said. “So it will stay flexible under increased pressure without becoming brittle.” That made sense; Diego had heard his dad talk about things like alloy properties, but it wasn’t like he’d ever studied them.

“And that means . . . ?” Santiago probed.

“It means that I can make a near ninety-degree full-throttle turn while absorbing the violent vibrations that would normally tear the motor out.” Diego shook his head. “How do I . . . know all this? I’ve never even worked on a gravity board. I don’t—”

“But you do,” Santiago said. He put his arm around Diego. “You saw it, Diego, just like I knew you would. Because you are my son.”

“Dad, that doesn’t make sense.”

“But it does. There’s a reason why I can build the things I build, why I can see how to bring together the technologies of the different times in a way that very few can. I have a gift.”

“You’re really smart.”

“No, it’s more than that. I have a . . . power.”

“What, like a superpower?”

“Not exactly. But it is, was, unique to me.”

“Were you born with it?”

“No, it manifested in me after I came to this world. I was sixteen the first time I used it successfully; I was volunteering to help build a well for the Natives living in the western territories. The design I came up with, everyone claimed it was impossible. The Steam-Time engineers said it was a miracle or maybe witchcraft, but an old Algonquin shaman there called it something else . . . the Maker’s Sight.”

“A shaman,” Diego said, trying to fit all this into the nuts-and-bolts image he’d always had of his father. “The Maker’s Sight? And you’re the only one who has it?”

“Maybe not the only one. The shaman said that she’d seen this kind of thing before, but she wouldn’t speak of it further, except to warn me to keep the power secret. And I have, until today.”

“You knew I had it,” Diego said. “Didn’t you?”

“Yes, but not until today. Your mother and I always suspected that you might inherit the Sight, but we were never quite sure.”

Diego peered up at his father. “Why today?”

“I can’t say. But this morning at breakfast I saw these flashes of light in my mind that tingled and burned. They reminded me of how I experienced the Sight, but they weren’t quite the same. In between each flash, I saw the gravity board. I suspected that the power had come alive in you, but I couldn’t be sure until we came down here. When you first gazed at the unfinished gravity board, I could feel the Maker’s Sight in you . . . around you, coming off you in waves.”

“So are you saying that it, like, runs in our family?”

“Yes, but it begins with me. Or, more precisely, with the Time Collision. Before that, I was just a normal boy. The Sight is just another way that the world was made new.”

“And it lets you build things.”

“It shows me a series of images that allow me to make or fix anything. Like what you just experienced, but to use it at the level I do requires supreme concentration, and it takes years to master. I am not certain that this is what the power is for, or even the only way to use it, but this is what I have chosen to do with it. In the world after the Collision, building and fixing things seemed like the best way for me to help the world.”

“So,” Diego said, “what am I supposed to do with it?”

“I’m not sure. It may be the same, or it may have a different purpose that is unique to you. You will figure that out as your Sight grows.”

Diego looked back at the board. If he could assemble the parts needed to construct the gravity board, what else could he make? “What’s the best thing you’ve used the Sight for?” he asked.

“I’m not sure. I never really thought of it like that.”

“Come on,” Diego said. “Did you ever enhance the fighter planes, like with better engines or weapons? Or, like, what about robots that could seek out the Aeternum to defeat them once and for all?” Diego remembered the picture of his uncle Arden and his parents. “Then maybe Uncle Arden wouldn’t have died in the Battle of Dusable Harbor—”

“No,” Santiago said. He’d stiffened, his gaze lost in the table. “During the Dark Years, my first instinct was to build machines to match the violence around us, and to save lives. I saw so many terrible things in the Chronos War: Mid-Time towns gouged apart by Steam-Time cannon fire while their armies were laid waste by Mid-Time missiles, so much violence brought on by people’s hatred of each other’s time culture. But the thing was, there were so few humans left, a superior weapon might have ended the conflict, but it also would have caused unforgivable destruction, and I didn’t think humanity could survive it.

“I realized that to survive in this world, what we really needed was each other. Mid Timers and Elders needed the Steam Timers. And as much as they hated to admit it, Steam Timers needed us, too. The Steam Timers had technology that still worked, the Elders had their advanced science and medicine, and the Mid Timers could bridge the gap.

“Now, years later, this world faces an enemy more dangerous than we ever faced during the Chronos War. We can beat the Aeternum, but not through the creation of superior weapons. It must be through our prosperity and by making a stronger world. Does that make sense?”

“Sort of,” Diego said. “But just making the world more prosperous won’t stop the Aeternum, will it? Not like a better fighter plane. Why not show them how powerful you are? Then they would fear you.”

Santiago sighed. “In my experience, fear never leads to freedom. This was proved true all too often in the world before the Time Collision. Making the world more prosperous will rally the people to stand against those who’d take their future away from them.”

“Could you build defenses then? Instead of weapons. You know, like shields, or . . .”

“Diego, that’s not the point. I understand where you’re coming from, son, but the power has to be used carefully,” Santiago said. “There are those who would use it toward selfish ends, and still others who would fear what we can do and want to destroy us because of it.”

“Destroy us?” Diego repeated. “Who would want to do that? You mean like the True Believers?” The True Believers were Steam Timers who had become time supremacists. They wanted to form a society free of Mid-Time and Elder influence.

“Perhaps,” Santiago said. “By combining their technology with that of the Mid Timers and Elders, I do what they are sworn to stop. And we know how ruthless they can be.”

“There’s more of them around town now, too,” Diego said. “There are even Believer gangs at school these days.”

“Yes,” Santiago said. “That is why, for now, you must keep this power secret, as I have. For our safety, for our family’s safety.”

“But for how long?”

“Until the world evolves. We are still a civilization healing from a traumatic wound. Much of the hatred comes from people’s fears. They want to hold on to what little is left of what they know rather than embrace what they could learn.”

“Was your old time better than this one?” Diego asked.

“No,” Santiago said. “It was different: in some ways better but in other ways much worse, despite what the Believers say.”

They both fell silent. The din of the outside streets bled in through the walls. Diego gazed at the gravity board, trying to comprehend everything he’d just learned.

A rolling sound reached his ears, and Daphne barked.

“Heads-up!”

Diego turned as Petey Kowalski swept through the door on an old skateboard. He swerved to avoid Daphne, who hopped excitedly on two legs.

“Good girl,” Petey said. He bent down as he passed and tried to rub Daphne’s head, but lost his balance and stumbled off his board. He careened into the table, catching himself against the edge as the skateboard shot across the room and smacked into the far wall.

“Whoa!” Petey said, breathing hard. “Almost lost it.”

“Almost?” Diego said.

“Well, I mean, I was just—Oooh, no way!” Petey spied the gravity board.

“Birthday present,” Diego said.

“And we are going to ride it to school, right? Tell me we are going to ride it right now!” Petey exclaimed.

“The board is only safe for one rider,” Santiago said.

“Dad,” Diego said, “could we bring Mom’s board to school so that Petey and I could both ride during lunch?”

“Hmmm.” Santiago scratched his chin as if deep in thought. “You do deserve some birthday fun. Okay. If you promise to be careful with it, and if you clean up these tools before you leave.”

“Definitely!” Diego said.

“It’s not like you haven’t tried the boards out before.” A smile played at the corners of Santiago’s mouth.

“Um . . . ,” Diego said.

Santiago laughed. “It’s okay, son. You’re old enough now to pilot one yourself anyway.”

“Oh hey,” Petey said, “I ran into your mom on my way down. She’s looking for you, Mr. Ribera.”

“I wouldn’t want to keep her waiting.” Santiago gave Diego a meaningful glance and then patted him on the back and headed for the door. “Have a good day at school. Remember, the power plant. Don’t be late.”

“Right,” Diego said, knowing that glance had been about the Sight. Telling no one included Petey, which would be tough. “And thanks again!”

“Whoa, D, look at this, huh? This board is berries!” Petey ran his fingers over the smooth surface.

“It’s pretty great,” Diego agreed, gathering the tools scattered across the workbench and sliding them into drawers. “It flies real smooth.”

“I thought you just got it?”

“Oh, right,” Diego said. He’d been thinking about his dream. “I mean, I’m sure it’s going to.” He crossed the shop and started hanging tools in their correct places on the far wall.

“What’s this bot doing back here?” Petey’s voice was coming from a different spot. Diego turned to find that he’d climbed up into the cockpit of an eleven-foot-tall robot that Diego had nicknamed Marty. “I haven’t seen him since you built him last summer.”

“Yeah, with Dad’s help. Now be careful; he’s back in the shop for repairs.”

“Okay, sheesh, settle down.” Petey put his boots up on the controls and laced his fingers behind his head. “He’s fine, but not nearly as cool as Redford.”

“Yeah,” Diego said. “Redford came out great.”

“That still blows my mind,” Petey said as Diego coiled a hose from the floor. “You saw that old red tractor and turned it into a giant robot. Someday you’ll be even more talented than your old man.”

“Mmmm,” Diego said. “Actually, Marty could do circles around Redford, but yeah, Redford has the best origin story, for sure.” They’d discovered the tractor out past the perimeter wall, searching for parts in the northern wild lands.

“Yeah!” Petey agreed. “Hiking along, keeping our eyes peeled for Algonquin warriors. And then running into that dimetrodon. I’m still pinching myself to make sure we survived that! It was like being Bartholomew Roosevelt, or a mercenary explorer or something.”

“I know,” Diego said. Actually, it had been terrifying, but if Petey hadn’t walked across that angry giant reptile’s nest, they would’ve never run and hid in the pile of abandoned tractors where Diego had found Redford.

A horn sounded from out on the canal.

“Ah, shoot,” Petey said. “School bus boat!”

“We should go.” Diego yanked up the last of the hose and tossed it over on the bench.

“My mom’s going to kill me if I get another tardy.” Petey scrambled to sit up.

There was a shrill whine and a grinding of gears, and Marty lurched forward from his spot.

“Ahh! Sorry!” Petey cried. “I kicked something!”

“Petey! He hasn’t been properly oiled. . . .” Diego had barely moved when Marty took another lumbering step and then froze up in midstride.

“What did I do?” Petey said, throwing up his hands.

The robot lurched sideways and crashed over onto his back, shaking the whole building.

“I’m stuck!” Petey shouted.

Diego rounded the side of the bot. He reached the cockpit and tried to pull open the hatch, but it was jammed. Smoke poured from the seized-up gears.

“Petey, shut it down!” Diego shouted over the earsplitting hiss.

“What?” Petey shouted back.

Diego prodded at the cockpit, trying to point at the controls inside. “Shut it down! Right there! If those gears stay seized up much longer, they’ll be warped and ruined.” Not to mention cause a dangerous fire.

Petey inspected the controls. He placed his hand over a large yellow button. “This?”

“No, Petey! Not that—”

But Petey slammed his hand down.

“Jeez, Petey,” Diego said, rubbing his shoulder.

“Sorry,” Petey said, shaking his head.

Daphne barked, hopping away and nursing one leg.

Diego scrambled to his feet and hurried back to the robot. He leaned into the cockpit and hit the shut-down button. The leg stopped hissing.

Outside, the bus horn blared again.

“Aw, man,” Petey said. He rushed over to the window and peered out. “There it goes. What are we going to do? Boy, am I gonna get it!”

“Hold on,” Diego said. He glanced to the corner of the shop, where a small vehicle was covered by a tarp, and hurried to it. “How about this?”

He threw the cloth aside, revealing one of Diego’s favorite father-son creations: an orange-and-white 1960 BMW Isetta that had been converted into a submarine. Petey had even managed to build the periscope for it.

“The Goldfish!” Petey shouted. “Your dad won’t mind?”

“Nah,” Diego said. “It’s my birthday. And he definitely wouldn’t want me getting a detention for being late. I need to work with him this afternoon.”

“Great. But we still need to hurry,” Petey said.

“Yup.” Diego darted over to his father’s desk for the keys. “Ah, shoot.” Dad’s stuff was scattered everywhere. He was going to be so annoyed, but Diego did not have time to clean this up, too. He scoured the mess for the keys but couldn’t find them. Dropping to his knees, Diego looked under the desk, then finally spotted them under the propane tank.

Daphne hopped over beside him and started yipping excitedly.

“Not now, girl,” Diego said, “I’m busy.” He strained to reach the keys, but they were beyond his fingers. Crud, he thought, glancing around. I’ve got to get those keys! He grabbed a pencil off the desk and tried with that, each time to no avail. Have to get them—I just have to.

Daphne’s rapid panting became slow, even breaths, and then she darted forward, flattening herself and scooting under the tank. She slipped back out with the keys in her jaws.

“Whoa, good girl!” Diego said. He bent down and held out his hand. As Daphne dropped the keys onto his palm, Diego saw a strange, silvery glint in her eyes . . . but then Daphne trotted off, tail wagging, like nothing had happened.

“All right, Daphne!” Petey said, standing behind him.

Diego stood. He watched Daphne go, his head tingling, similar to the way it had after building the gravity board.

“What’s up, D?”

Diego shook his head. He figured he was still a little woozy from his experience with the Sight earlier. A ghost of a headache knocked at the back of his skull, and Marty throwing them across the room hadn’t helped. “Nothing,” he said.

“Come on, man,” Petey said. “We need to scramble.”

“Right.”

“Should I get your mom’s gravity board?” Petey asked.

“Nah, I’ll get it,” Diego said. “You’ve caused enough trouble.” He smiled and punched Petey in the arm, then hurried around the shop, putting a few more things away and grabbing the two boards.

Petey and Diego pushed the Goldfish into the freight elevator and rode to the ground floor. Petey sat in the passenger’s seat as Diego ignited the main boiler. The little car chugged to life. Diego hopped inside and jammed the control levers. The car rolled down the street-level dock and into the green water.

Horns sounded in the traffic-clogged canal as Diego veered among the slower paddle wheelers and faster boiler taxis while watching out for the tromping legs of robots. The little craft was barely visible to the larger ships, sitting just above the water as it did.

As the world bustled around them, Petey pulled an old Sony Walkman cassette player from the glove box and plugged in the cable from a simple set of speakers in the back.

“Which one of these do you like?” he said, flipping through a stack of plastic cassette cases. Petey handled these gingerly; in his house, he was used to music being played from delicate wax cylinders.

“That one,” Diego said, glancing over.

“The Replacements,” Petey said. “Which song?”

“‘Can’t Hardly Wait,’” Diego said. “It should be cued up.”

Petey slid in the tape, and the speakers burst to life.

“Your dad’s music is loud!” Petey shouted.

“That’s the best part about it!”