Читать книгу Drago #3 - Art Spinella - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER FOUR

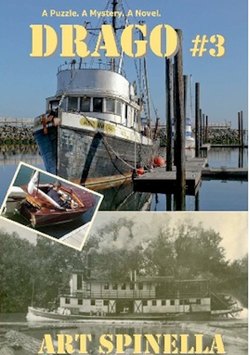

Оглавление9:30 p.m. Coquille River. Calm water ebbing to the ocean. Cookie, in Miss QT, waited near shore about a mile upstream of Sal who sat in the Smokercraft docked at Rocky Point. I was aboard Dragonfly in the Bandon harbor, two-way radio clicked on, a pot of coffee on the galley stove, mug filled to the brim in my lap.

The night glistened as only a smog-free rural ocean-front sky can. Most businesses in Old Town were long closed and no one was aboard the few boats in the marina. Night-lights were clicked on in a couple of the moored fish boats, but they gave off a dim glow, adding warmth to the cool breeze.

There’s something magical and dangerous about the Coquille River. Much of its history is tangentially known to residents. Well, except those under the voting age who think history started the day they were born.

With the slow rocking of Dragonfly on calm swells, I pulled up some info from the deep dark recesses of my memory. Between sips of coffee and flashes of images of the ghost paddle wheeler, dingerberries of those historic facts.

From the early 1870s through the mid-1940s, the Coquille was recognized as a beneficial project by the federal government, with the political assistance of long-time resident George Bennett.

Politics wasn’t that different back then. With veiled threats of votes hanging in the balance, Bennett offered advice to political candidates: Whoever provides the greatest assistance to improving the Bandon bar and river would be elected to Congress.

The threat was taken seriously and Senator John Whitaker quickly introduced a bill in 1880 to grant $10,000 to Bandon for harbor improvements. With much more to come.

He was easily re-elected.

Additional funds poured in over the coming 20 years, extending the jetties, removing rock from the Rocky Point location where Sal was moored this night and extensive dredging to 10 feet from Bandon harbor to Riverton – about 18 miles upriver – and nine-feet from that town to Coquille, another six miles upstream.

The town became a mini-powerhouse in shipbuilding. By 1888, nearly a dozen sea-going ships were constructed, the first being the schooner Ralph J. Long. On its maiden voyage to San Francisco, it carried 120,000 board feet of lumber, a ton of bark, a ton of wool and five tons of oats.

But it wasn’t the first ship to use the Bandon harbor.

Before Bennett’s threat, coastal-trade schooners were frequent visitors to Bandon as early as the 1860s.

Development, though, stimulated construction of river boats – mostly sternwheelers -- to connect the city of Coquille with Bandon, transporting goods and passengers who were slated for passage to San Francisco and as far north as Alaska.

“Hey, Nick,” came the voice from the dock. Stan Moorly grinned at me and began to board. “Saw the light on in the cabin. Could smell the coffee cookin’.”

“Want a cup? It’s on the stove.”

He wandered into the cabin and returned a minute later with a chipped old mug, steam billowing.

Pulling up a chair and settling in, “Waitin’ for something important or just hangin’ out reminiscing about your single days on Dragonfly?”

“Just thinking about this harbor and its history, is all.”

Moorly took a long sip of brew.

“My granddad was one of the riverboat people in the day. Told some stories about the paddle-wheeler wars back then. Early 1900s.”

“Yeah?”

Moorly pulled out an old pipe, as gnarled as a fisherman’s hands, dipped the bowl into a leather pouch for some tobacco and with all the care of a man on the deck of a ship in a roiling sea, carefully cupped his hand over the bowl and lit the tobacco. Drawing on the stem, a cloud of smoke with the sweet odor of cherry hung in the air.

“Old west, Oregon style,” he said. “Worked for the Myrtle Point Transportation Company back then. Deckhand on the Telegraph. Company owned eight sternwheelers, racing up and down the river carrying milk and passengers and crates of whatever.”

He leaned close to me, “And opium. Think the marijuana growers were the first druggies in the state? Think again. Opium was big business back then.”

“You’re kidding.”

“Nope. Look it up.”

Another cloud of cherry smoke and a long sigh as he tilted his head back and spoke with a voice sounding like gravel in a drain pipe. “In fact, because the British had a trade deficit with China back in the 1800s, they encouraged opium use there so they could sell it to the Chinese and balance their trade books. Worked pretty good, actually.”

I laughed. “Everyone these days has a trade deficit with the Chinese.”

“The Brits actually had fleets of opium ships. They’d sell the stuff to Chinese middle men who would trade for tea which was big business back in Europe.”

“And our little town was a port for the drug?”

“Morphine, mostly, Nick. That’s what opium is. Yeah, Oregon was a hot bed. Back in 1870-something, the paddle wheeler Orpheus and the full-rig Pacific collided up near British Columbia; the manifest showed what went down, aside from all but one of the 275 passengers and crew on the Pacific. On the list, two cases of opium headed to San Francisco.”

I reached into my back pocket and pulled out the photo of the twin ghost paddle wheelers.

“Never occurred to me to show you this, but can you ID either of these ships?”

Leaning across, Moorly took the photo from me.

“Look like you got some problem with your lens.”

He paused, moved the photo closer to his eyes, pulled on the Meerschaum and smiled. “Well, dang, that one there is the Dora. Granddad had a picture of it in his living room. All framed up. He was a deckhand on Dora for three years.”

“What about the other one?”

“Pretty fuzzy picture, Nick. Why’s it look like that?”

“Remember the legends about the ghost paddle wheeler?”

“Sure. Bunk. Granddad believed in it, but he was in the minority.”

“Something about the captain being murdered and the ship scuttled.”

Moorly closed his eyes and drew a few puffs from his pipe.

“You want the whole story or the one we tell tourists?”

“Ain’t no tourist. Try the whole thing.”

He never got the chance.

The walkie-talkie hissed. Cookie’s voice broke through the static. “Nick! It’s here!”

Pressing the talk button, “Where exactly?”

“About a half mile up from Rocky Point.”

“How close are you?”

“Maybe a quarter mile. Saw a sparkle and then it was as big as life! Wow!”

“Getting this, Sal?”

“Got it.”

“Cookie. Close in as fast as you can. Can you catch it?”

“In this boat, no problem.”

Before she clicked off I could hear the outboard’s nasal exhaust spin up and could picture “Miss QT” rise up on her plane.

“Sal. You ready?”

“Set.”

“Got your gun?”

“Sure. Why?”

“I want you to shoot at it as soon as it gets within range.”

“What?”

“Cookie.” No answer. “Cookie.” Still no answer. “Hey, Cookie, you there?”

Her voice came back stressed. “Geez, Nick! I’m off its starboard side. I can’t get close! It’s like it’s not letting me get close! Keeps pushing me back.”

Silence.

“Cookie?” My heart began thumping. “Cookie!”

“See her, Nick!” Sal broke in.

“Wave her off and pick up the trail, Sal.”

“Will do.”

Moorly’s eyes were wider than the Mississippi at flood stage. “What the hell is going on?”

“Ghost paddle wheeler. Your granddad was right.”

I threw myself from the chair and crashed into the cabin. Lit up the Buddha diesel and yelled out the pilot window, “Set me free, Stan!”

He jumped from his chair, clambered to the dock and quickly untied the bow and stern lines while I throttled in reverse out of the slip. Moorly jumped back on board.

“Ain’t leaving without me, Nick!”

I waved an okay, spun the wheel hard to port, clicked into forward and throttled up.

“We’re at the bridge, Nick!” Sal’s voice.

“Did you shoot at it yet?”

“Are you sure…”

“If it’s a ghost ship, Sal, it won’t matter! Already dead! Just make sure you aim low.”

“Gotcha.”

In the distance I could hear the bellow of a .45 revolver echoing across the river. It sounded puny at this distance, but no doubt what it was.

I pulled the Dragonfly to the mouth of the boat basin and waited, idling, adjusting our position with little clicks of the throttle, steering.

“Sal! Is it the boat with the crew or the boat without anyone on board?”

“No one on board!”

“Cookie, where are you?”

“About a quarter mile behind Sal and the ghost ship.”

“Stay back.”

“Nick, is Sal shooting at it?”

“Yes.”

“I can’t leave you guys alone for a minute!”

“Stay back and out of the line of fire, okay?”

“Don’t worry.”

I saw the glow on the water. Eerily snow white. Shimmering. Stark contrast to the blue-black sky and inky river. My pulse notched up.

“Holy tamale,” Moorly said under his breath as he unconsciously pounded the bowl of the pipe on the railing, sparks from the burning tobacco cascading into the water. “Look at that.”

As it came closer, the vapor cloud began taking form. First the general outline of a paddle wheeler then more details. The barrels, bales and windows becoming more clear even if they were still like gauze.

“It’s the Dora!” Moorly said. “By God, it’s the Dora!”

The rear paddle wheel spun quickly and evenly, the bow cutting a wake, the creaking of the deck boards increasingly clear to the ear.

It passed us at 10 or 12 knots. Gaining speed. Sal in the Smokercraft now tailing it, 20 yards back.

I gunned the throttle, which on a single-cylinder Buddha is like pulling your foot out of thick mud. I aimed ahead of the Dora bow, hoping to intersect before getting to the bar.

But the Dora continued to increase speed. I wound up some 10 yards back, between Sal and the paddle wheeler. Dragonfly could make 8 knots, so we were quickly falling behind as we hit the bar.

And then it was gone. A quick blip and sudden darkness.

My heart dropped out of my chest. Another miss. Right plan. Bad execution. Next time.

I pulled Dragonfly back to its berth, shut down the engine as Moorly tied up the little trawler.

“Well, Nick, that was exciting. The Dora. Who would have thunk it.”

“I’ve got to catch it, Stan. And I will.”

My Smokercraft pulled into the basin followed by Miss QT. Both boats hovered near the stern of Dragonfly. Sal stood behind the control panel.

“Any luck?” he yelled.

I shook my head. “What happened when you shot at it?”

“Nothing. Absolutely nothing. No puff of smoke as the bullet went through the boat. No disruption of the image whatsoever. Like it wasn’t even there.”

“Damn.”

“But I got some infrared photos of it.”

“Good thinking, Sallie.”

Cookie added, “I need some scrambled eggs and sausage.”

________________________________________________

We invited Moorly to join us, which he did gladly. Seeing the Dora had more than piqued his interest. It had turned him into an instant believer in ghost ships.

Sal rumbled to his house to develop the infrared photos and returned a half-hour later with a large manila envelope and a Cheshire cat grin.

“Got something?” I asked.

“After breakfast.”

Moorly was looking around the dining room and living room, staring at photos and trying out the couch then the lounge chairs. Cookie had given him special dispensation to smoke his pipe “As long as you only use that cherry tobacco.” The smoke followed him around the room as he puffed his way through a second bowl.

It occurred to me he’d never been to Willow Weep. I’d always caught up with the fisherman at the docks or in town.

“Nice place, Nick.”

Finally he sat at the table. “That was the most amazing thing I’ve seen,” he said for what seemed to be the hundredth time. “Why don’t you look happy, Nick?”

“Because it wasn’t the ghost ship we were looking for.”

Moorly tapped the tobacco in the bowl of his pipe. “There’s more than one?”

Sal and I nodded.

“By jiggers.”

“You could say that.”

“By jiggers.”

I laughed. “Once was enough, Stan.”

Cookie brought in a giant skillet of scrambled eggs, a couple dozen sausages and a huge pan of chorizo. Nothing tastes better at 3 a.m. than breakfast in a warm room on a cool night. We ate in silence, each of us reflecting on what we’d seen.

“What can you tell me about the Dora, Clarence?” Cookie finally asked, cupping her chin in her hands after pushing her empty plates to the center of the table.

Moorly reached deep into his jacket pocket and pulled out the Meerschaum, holding it up and getting a nod of approval from my wife.

“Well, it was built up around Randolph in 1910 or so. Passengers and freight duty, mostly. Owned by the Herman family who also had their hands into many Coquille boats including the Telegraph, Charm. Others.”

He put a lighter to the sweet cherry tobacco and puffed a billow of smoke.

“Dora worked the river til the late 1920s and eventually was abandoned at the Ward Ranch. There’s a great picture of it and the Telegraph beached and decayin’. Kinda sad. But wood was plentiful. Building boats on the Coquille was relatively cheap and once the costs were covered, t’wasn’t no environmental rules that said you couldn’t just abandon the hulk wherever you wanted. So those two old sternwheelers rotted away right before your eyes.”

He puffed and shrugged.

Sated, the four of us took up various seats in the living room, fresh coffee all around.

I started. “Debriefing time. Let’s put it all in order.”

Nodding to Cookie, she said, “There was a single blip and then the Dora was on the water about a quarter mile in front of me.”

“Color?”

“Only shades of black and white, far as I could tell. Pretty indistinct outline of the boat.”

“Any sound when you saw the blip?”

She closed her eyes, reliving the sighting.

“Just the river, then the blip. You know Miss QT’s engine isn’t real quiet, Nick, so if there was a sound I wouldn’t have heard it, probably.”

“Length?”

“Maybe 65 or 70 feet.”

Moorly interjected, “The Dora was 70 feet.”

“You said you couldn’t get close to it,” I pressed.

“It was odd. I caught up to it pretty quickly…”

“How fast was it going?”

“Maybe five or six knots.” I nodded. She continued, “But when I tried to get closer than 30 feet or so, it was like I was pushed away. And it was colder than ice. The temperature dropped 20 degrees as soon as I got within 40 feet.” Sitting on the couch, she pulled her legs up under her. “Every time I’d try to slip closer, I’d get dragged away or something.”

Sal grunted. “Miss QT’s got a pretty flat bottom. Could it have been the wake?”

Cookie thought it over. “Maybe.”

I turned to Sal. “You’re up, big man.”

“Saw Cookie and the paddle wheeler up river about a quarter mile. Fired up the boat and untied.” Sal was a stickler for debriefing details. “When the paddle wheeler was about a hundred yards upstream, I edged out at an angle to intercept. I ran parallel on the starboard side, grabbed the camera and clicked off three shots. No sound from the boat. No distinguishing colors. I couldn’t read the name.” He looked at Moorly, “Thanks Stan. Now we know it was the Dora.”

The fisherman nodded.

“Like Cookie, I tried to get closer but was pushed away. But it felt like a big wake rather than anything mystical or ghostly or like the Hand of God keeping me at bay. And it was indeed colder. Noticeably. At least 20 degrees. Maybe more. Powered up a bit, but the Dora kept going faster. Maybe 8 or 9 knots at this point.”

“When you went under the bridge, did it flash or flicker like the last time we saw it?” I asked.

“Yes, actually, it did. I was getting to that. It was as if the bridge caused interference of some sort. You know, like when a hail storm disrupts your satellite TV signal.”

“You’re getting mighty close to suggesting it was an electronic image. Hologram, maybe,” I said, somewhat disappointed, but more interested in finding out the reality.

“Nick, I’ve done work with people who know holographic science. This is a moving, very large image we’re talking about. Complete with a moving paddlewheel and a wake. It’s three-dimensional and gauzy.

“Holograms are static images. The moving variety requires a screen of sorts. Besides, it would take massive computer power to pull off that kind of hologram. I mean massive. So, yes, I’m doubtful.”

“And when you shot at it?”

“At first I thought you were nuts, but actually it made sense. I put three slugs through it. Nothing changed. Nothing like a bullet trail through smoke, for instance. No reaction at all. It just kept on truckin’.”

Moorly laughed, “So you’re saying it’s a ghost ship? That’s your only alternative.”

I answered, “As much as I hate admitting the likelihood, if it’s not solid, not a projection, we’re running out of options.”

Sal had been toying with the edges of the large envelope he’d brought from his place. I wasn’t going to ask about the photos. I knew he’d bring them up when the time was right.

The time was right.

He flipped open the flap and pulled out three 8x10 prints.

“Interesting images,” he said.

He passed one to me, one to Cookie and the last to Stan. I could tell they all looked pretty much the same. From what I could tell, no paddle wheeler in any.

“Note that there is no picture of the Dora,” he started. We all nodded.

“Not much of nothin’” Moorly said.

“Not quite, Stan. What do you see at the waterline?”

We all pulled the photos closer to our eyes as if that would somehow strip away a veil of secrecy. Of course, all it did was give me eye strain.

“Actually, hold them further way, not closer.”

Like monkeys, we all did as we were told, pushing them out to arm’s length.

“Smears,” I said. “What am I lookin’ at, Sallie?”

Moorly added, “It looks like the phosphorescent skim sailors have seen.”

I’d witnessed the phenomenon over the years piloting Dragonfly around the Pacific. The glow appears at night and there are stories of aircraft pilots who followed it home when all other forms of navigation failed.

Sal pointed out, “Correct. It’s not a heat signature, per se, but a reaction to atomic disruptions.”

I cut Sal a glance. “CIA?”

“Never was, nor would I ever be… As I said, I’ve worked with scientists who know this stuff. You pick it up along the way. I also cheated and Googled it after I saw the photos and returned for an excellent breakfast.” To Cookie. “Thank you ma’am.”

Cookie nodded and smiled. “Welcome.”

Sal continued, “There’s a lot of long words involved, but basically it’s a heat signature without the heat.”

I gave myself the Bandon head scratch. “What’s it all mean?”

Sal grinned. “Beats the hell out of me. Maybe if we get some sleep we’ll have a better idea with clear minds.”

Stan was first to stand. “Ain’t been up this late since… well, forever, actually. I’ve been up this early to get out of the harbor. But never been up this late, if you know what I mean.”

Cookie bade all a good night and went about the business of clearing the table while Sal, Stan and I walked outside.

Sal clicked on a small key-chain flashlight to see his way home and with a raised arm called over his shoulder, “Lunch. Minute Café. Noon.”

Stan and I crossed the gravel drive to his Ram diesel pickup.

“Cookie’s a good one, Nick. You lucked out.”

“That’s the truth.”

“Heard you were married once before.”

“For about seven minutes.”

“Where’s she now?”

“Got hit by a log truck.”

“Dead?”

“Stan, she got hit by a log truck.”

He mulled that for second. “That would make her dead.”

“As a mackerel.”

He climbed into the cab, fired up the diesel and backed out of the drive.

I was walking back inside when the thought struck me. Stan’s mention of my ex snapped a synapse in my brain.

“Well, Jesus H. Christ.”