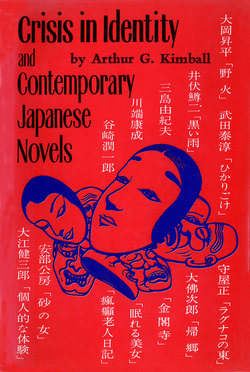

Читать книгу Crisis in Identity - Arthur G. Kimball - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление3

AFTER THE BOMB

It took Masuji Ibuse (1898-) over twenty years before he could properly defuse his own bomb, the one set ticking inside him by the great explosion at his birthplace in August 1945. But over two decades were necessary before he could articulate with his characteristic control, before he could set forth, with appropriate objectivity and aesthetic distance, the story he needed to tell. It is well he waited, for Ibuse is above all a stylist, relying to a greater degree than many of his contemporaries upon subtle contrasts, quiet touches of humor, and delicate shifts of nuance to carry his meaning. Of course more than aesthetic distance was involved. Ibuse's own identity was very much at stake. For one does not have to be melodramatic to assert that at least two generations of Japanese are not the same since the Hiroshima bomb. And Ibuse, with the added sensitivity that many Japanese feel for their place of birth, needed time to ponder, to sift through the details of the event, to evaluate, and to reevaluate again and again, what the world, Japan, and he himself had become and were becoming.

Black Rain evolves from a central gripping contrast.1 Ibuse sets a single event, the atomic explosion at Hiroshima, against the ongoing, quotidian necessities of existence; a death-dealing, molecule-reordering destruction and recreation via discontinuity confronts a life-preserving, life-maintaining process of continuity. To what extent will the one bend, change, and reshape the other? How will the other absorb, counter, and amend the first? The novel grows from such unstated questions. In the lives of the characters, centering on the small family unit of Shigematsu, his wife, and his niece Yasuko, Ibuse portrays a way of life, capturing not only the full impact of the tragic event, but the resilience of the human spirit in response.

Something of Ibuse's achievement emerges when one compares the style of Black Rain with that of John Hersey's popular Hiroshima.2 Hersey, Pulitzer prize-winning novelist and journalist, also had a story to tell; it is terse and dramatic. Six survivors of the blast struggle to comprehend what has happened to them. The reader follows, somewhat breathlessly, their alternating fates:

"For we are consumed by Thine anger and by Thy wrath are we troubled. Thou hast set our iniquities before Thee, our secret sins in the light of Thy countenance. For all our days are passed away in Thy wrath: we spend our years as a tale that is told..."

Mr. Tanaka died as Mr. Tanimoto read the psalm.

On August 11th, word came to the Ninoshima Military Hospital that a large number of military casualties from the Chugoku Regional Army Headquarters were to arrive on the island that day, and it was deemed necessary to evacuate all civilian patients. Miss Sasaki, still running an alarmingly high fever, was put on a large ship.... Pus oozed out of her wound, and soon the whole pillow was covered with it. She was taken ashore at Hatsukaichi, a town several miles to the southwest of Hiroshima, and put in the Goddess of Mercy Primary School, which had been turned into a hospital. She lay there for several days before a specialist on fractures came from Kobe. By then her leg was red and swollen up to her hip. The doctor decided he could not set the breaks. He made an incision and put in a rubber pipe to drain off the putrescence.

At the Novitiate, the motherless Kataoka children were inconsolable. (pp. 79-80)

The style is that of the journalist, making the most of his dramatic material. The quick, restless pace keeps the reader on the proverbial chair's edge. The abrupt transitions continually jolt him. Repeatedly, Hersey ends the brief sections within his chapters on a dramatic, almost melodramatic pitch:

But then the doctor took her temperature, and what he saw on the thermometer made him decide to let her stay.

The priests concluded that Mr. Fukai had run back to immolate himself in the flames. They never saw him again.

He went to bed and slept for seventeen hours.

When he realized what had happened, he laughed confusedly and went back to bed. He stayed there all day. (pp. 72-73)

Thus end consecutive passages. Like a boxer's series of left jabs, they keep the reader unsteady and reeling. When he is properly "set up," the moral blow is landed. "The crux of the matter," Hersey states plainly at the end of his book, "is whether total war in its present form is justifiable, even when it serves a just purpose" (p. 115). Just to be sure, Hersey throws one last punch. A primary school child's report of the bomb furnishes the book's final words. "They were looking for their mothers," the child concludes, "but Kikuki's mother was wounded and Murakami's mother, alas, was dead" (p. 116).

Hiroshima was a timely book.3 It furnished the English-reading West with a dramatic and exciting—but not too grisly-account of the event that terminated the war. It sold, and continues to sell, innumerable copies. Ibuse's work is of a different design, however, as the following quotation suggests:

A young woman who came along almost naked, with a naked baby, its face almost entirely covered with blood, strapped to her back facing to the rear instead of the normal way.

A man whose legs were moving busily as though he were running, but who was so wedged in the wave of humanity that he achieved little more than a rapid mark-time....

Shigematsu had reached this point in his copying when Shigeko called from the kitchen: "Shigematsu! Whatever time do you think it is? I'd be grateful if you'd call it a day and come and have your dinner."

"Right! Just coming." Getting up, he went to the kitchen. He had been putting off dinner until now, staving off hunger while he copied out his journal of the bombing by munching home-made salted beans. Shigeko and his niece Yasuko had had their dinner long ago, and Yasuko, who was catching the first bus to Shinichimachi in the morning to go to the beauty parlor, had already gone to bed in the box room. (pp. 58-59)