Читать книгу Standardized Education: Moving America to the Right - Arthur OSB Lieber - Страница 4

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

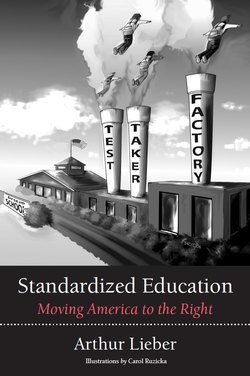

ОглавлениеIntroduction

Education Is an Art, Not a Science

WARNING: Much of what you read in this book will be contrary to the perspectives of professional educators. I take the point of view that the field of education is in many ways more accurately an art form than a science. I will draw conclusions that in many cases are subjective but consistent with the following quote that has been attributed to either Mark Twain, Casey Stengel, or Yogi Berra (all born in Missouri).

It ain’t what you don’t know that gets you into trouble. It’s what you know for sure that just ain’t so.

Coming from any of the three, it would have merit. Coming from all three it’s gold.

There are educators who can’t accept this level of uncertainty in their chosen field. If they did, much of what they said would not be worth the dollars they are paid to pontificate. Many academic positions in schools of education and educational bureaucracies would have to be eliminated. The reason is that so many people in these positions do not acknowledge the limitations of their knowledge. I have trouble with that as well. That’s why I’m inserting this caveat to warn you to be cautious about what you read in this book and to invite you to take exception with my assertions, as well as those of others.

While on the subject of uncertainty, I should mention that much of my experience in education comes from my fifteen years as a teacher and school director at Crossroads School in St. Louis, Missouri. I was twenty-six years old when several of us founded the school. We were all young and committed to providing a combination of traditional academics with a wide range of experiences outside the classroom. In educational parlance, this is called experiential education.

Often times we were asked if we were doing a good job. We were positively assessed by an established accreditation organization, the Independent Schools Association of the Central States. We were the topic of considerable discussion, since we were the sole private, nonsectarian high school in the city of St. Louis.

Were we a good school? Did we as teachers and administrators do a good job? My answer is that it beats the hell out of me. Or to quote Barack Obama in reference to a different topic, “It’s above my pay grade.”

All I can say is that we were the sum of many different parts. These included how we interacted with students, what we tried to teach, how students responded to what we tried to do, and how students responded to one another.

The impact of much of what we did was invisible to us, the students, the parents, and any professional evaluators. What were students thinking? Were teachers satisfied with what they were doing?

We did have tests and other various forms of evaluation. They gave us slender openings into what was happening in the lives of children. The conclusions we were able to draw were more like hypotheses and hunches as to how to proceed. They were not conclusive like the score of a sporting event where one team wins and the other loses. Presumably there would be more clarity about how effective we were with each group of students several decades after they graduated.

By virtue of the law of averages, we did some things well and we screwed other things up. If I were asked to categorize what went into each of these columns, I’d certainly make some mistakes. On balance, I think that we did well. But it was never at such a level for us or anyone else to crow about.

What happened at Crossroads is not unique. Every school is a mixture of experiences involving a number of people. Some of what happens is visible. Most is not. Just as I will resist the temptation to characterize what we did at Crossroads or what kind of school it was, I will suggest that drawing definitive conclusions about any school, school district, type of school, or education in general is fraught with hazards. In order for this book to have some meaning, I’ll make assertions because they help illustrate the dynamics of what is happening. But again, I caution you to read everything with a critical and possibly even skeptical eye.

Invisible is the operative word, because it places limitations on what can and should be measured. If much of what is happening cannot be seen, how can you accurately measure anything of meaning? Education has become a full-fledged social science. The key word is science because it is the ticket to gain and keep your bona fides in the world of academics. It is anathema to professionals to acknowledge that they often cannot see what they want to measure. If that is the case, why are they trying to measure that which can’t be accurately measured? The answer is predictable: because they can. They can because they get away with it. They will be able to so long as the public thinks that the numbers that they crunch about students and schools are meaningful.