Читать книгу The Gifts of Frank Cobbold - Arthur W. Upfield - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER ONE 1853 to 1867

Early Years

Оглавление1.

Francis Edward was born in Ipswich, Suffolk to Arthur and Sarah Cobbold. At the same time, the settlers of north-eastern Australia were agitating for separation from the huge southern state of New South Wales. Not only was he the seventh son of his parents, but he was the seventh son of a seventh son. This traditionally accepted sign of good fortune was to be substantiated through a long life of adventure and endeavour on the sea, among the islands of the New Hebrides, and in that part of Australia which Queen Victoria named 'Queensland' in 1859, when Francis Edward Cobbold was six years old.

Australia was to claim the boy from an early age and during this period it was rapidly emerging from being the depository for England's overcrowded jails. The great influx of free settlers was beginning to have its effect on the quasi-military form of government, and the public concern for democratic and responsible government resulted in colonies destined to be among the brightest jewels in the Queen's empire.

This new Eldorado beneath the Southern Cross called for men of grit and stamina, and did not fail to get them. British factories were demanding ever-increasing supplies of wool for their younger colony of Victoria when McArthur established the fact that sheep were ideally suited to be reared in Australia. The eyes of all adventurers in the world had begun to turn towards the south and the people of the British Isles were starting to realise that Australia was not, after all, a mere conglomeration of convict settlements but a land of great promise for those possessing initiative and determination.

It was only natural that one of the Cobbolds of Suffolk should be caught up by the enterprising stream flooding from England across the world to Australia.

2.

The earliest surviving records of the Cobbolds go back to Robert Cobbold of Tostock, a Yeoman farmer who died in 1603. He was followed by a succession of Cobbolds in direct line to Thomas Cobbold, who started a brewing business at Harwich in 1723. At this period, the water supply at Harwich was very unsatisfactory; Thomas Cobbold soon recognised the fact that successful brewing depended upon a pure water supply and arranged for water to be conveyed to Harwich down the river Orwell from Holy Wells Springs, Ipswich in especially constructed barges.

That condition of affairs did not satisfy him for long, however. It was not good business economics to bring the mountain to Mohammed, so he decided to go to the mountain, and the brewery was moved to the same water supply at Ipswich where the first Cliff Brewery was established in 1746. There, Thomas Cobbold extended his enterprises, becoming a farmer, a merchant, and a ship owner, determined to command the transport of merchandise and raw materials necessary to his business.

1. John Cobbold (1771-1860)

His son, young Francis Edward's great-Grandfather John Cobbold, extended his father's activities by a wharf and then building his own ships to be sent out to engage in foreign trade. At least eighteen units of this fleet carried the Cobbold house flag to the distant harbours of India and China. In size, they ranged from the 50 tons spritsail, Cliff, to the 366 tons barque, Dorsetshire, and an old picture shows the John Cobbold, 200 tons, helping a vessel in distress in a great storm in the Atlantic.

Determined to secure water rights for his brewery at Ipswich (named the Cliff Brewery) John Cobbold purchased the Holy Wells Estate in 1780, built a mansion on it and afterwards extended the boundaries of the property. The house was to witness the succession of five John Cobbolds in direct line, the last to live there being John Dupius Cobbold who died in June 1929. The sixth John Cobbold and his son, the seventh John Cobbold, now reside at Glemham Hall, ten miles distant from the old home of the family.

Holy Wells, Ipswich

John Murray Cobbold (1897-1944) was killed when a flying bomb hit the Guards Chapel during Sunday morning service on 18th June 1944 and his son (the seventh) John Cavendish Cobbold (born 1927) died in 1983. Glemham Hall passed to younger brother Patrick Mark Cobbold (1934- 1994) and thence to the present owner Philip Hope-Cobbold.

From the Tostock yeoman farmer sprang a dynasty as proud of its history and of its family as any that ruled an empire. The traditional line of descent was rigidly maintained, the eldest son automatically inheriting the major portion of his father's estate. The records of the family prove that its strength has never diminished, and that the attributes of business flair, foresight, and rigid rectitude have been passed down from one generation to the next.

In course of time, the original brewery was replaced with one fitted out with all the most approved appliances and constructed by the Cobbold staff from the Cliff building yard. The resources of the river were developed and the Cobbold docks, warehouses and maltings spread out over ground which had originally contained riverside gardens and merchants' houses. The Cobbolds grew with the growth of Ipswich, which they assisted to grow. As Punch pertinently put it:

Why is Ipswich like an old shoe?

Because it is Cobbold all over.

3.

On 17th October 1831, Mrs Bowditch Lee wrote to a young lady about to take her place as a governess in John Cobbold's family. She gave vivid little character sketches of every member of the family, and of the master of the house she wrote:

'Mr Cobbold is a fine, handsome man, between 50 and 60, full of native talent and shrewdness, abounding in kindness, liberality and generosity, indulgent to his children, full of honourable and manly feelings, and replete with that excellent quality, common sense'.

Of Mrs Cobbold, Mrs Lee wrote:

'Mrs Cobbold, who must have been beautiful, is a stout little woman, with a countenance beaming benignity … her whole life is spent in doing kind actions to others, or trying to do so … there is not a creature that she ever heard of that she does not wish to make happy. Having reared fourteen children, all of whom are living, you will readily suppose that her energy of character and her bodily activity have been constantly called into action'.

At this time the eldest son, John, was 'High Bailiff and a lawyer in great practice'; the second son, Henry, 'is a complete contrast to Mr John. He tries to hide a great deal of good and fine feeling under a blunt and rough manner …'; a married daughter is 'a charming person, full of talent, taste and kindness'; and Frank is a 'perfect hero in person, and is highly gifted with ability and taste, and he is a good conscientious clergyman ….'

Mrs Bowditch Lee goes on to list and describe in detail other members of the family, thus: 'Mrs David Hanbury, another married daughter, is an elegant-looking, handsome woman ….'; 'Kate is one of the sweetest, the mildest and best human beings ….'; 'Agnes is beautiful and extraordinarily gifted in every respect ….'; 'Emily is not so handsome, but quite enough to turn a person's head ….'; 'Harriet is a dear pale, black-eyed, silk-ringletted girl, bounding about like an antelope ….'; and 'Kate is engaged, but obstacles exist at present on the side of the gentleman's family'.

The youngest of the family was Arthur, then aged 15 and at school at Boulogne. He was the seventh son and was to become the father of Francis Edward Cobbold, whose career is to follow.

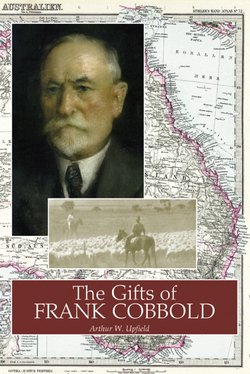

3. Arthur Thomas Cobbold (1815-1898)

4.

A picture of Francis Cobbold's father Arthur, made during the closing years of his life, shows a strong family likeness to his ancestors - the same strength of mind and the same physical strength, the same determined jaw, and the same facial sternness when in repose - a sternness somewhat belied by the straight nose and the widely placed eyes. Born in 1815, he lived to reach his eighty-third year - longevity being another feature of his forebears.

In due time he married Sarah Elliston who, like her husband, lived to a ripe age and reached her eight-sixth year. They had ten children, the subject of this biography being the eighth child and, as mentioned earlier, the seventh son.

4. Sarah Cobbold, nee Elliston (1814-1899)

The Ellistons were a yeoman family of Suffolk - the earliest recalled being Robert Elliston of Monks Eleigh - and more than one member of this family distinguished himself. One of Sarah Elliston's uncles was a naval lieutenant under Admiral Boscawen when he defeated the French fleet off Gibraltar in 1759; he had reached the rank of Commander when he retired. Another uncle - William Elliston - was a member of St. John's College, Cambridge, receiving his degree in 1754 with the distinction of fourth wrangler and in 1760 he was elected Master of Sidney Sussex College, a post he held until 1807.

Yet another uncle, Robert William Elliston, was a comedian-actor, manager who was at one time the proprietor of Drury Lane Theatre. Of him it was said: 'He had never been excelled and seldom equalled'.

Issue 18 of Phaeon, the Sidney Sussex Newsletter, described William Elliston as 'the Master from 1760 to 1807 who transformed the College into a place of high standing in the University after a hundred years in the shade'

5. The children of Arthur Thomas Cobbold and Sarah Elliston

5.

It can never be fully established that the seventh son of a seventh son is definitely lucky. After all, luck is much less a matter of chance than the result of long planning, and the sense to take a firm hold on an opportunity before it passes by. It is also preferable to be born lucky than to be born rich - this truth may be illustrated by the incident of Francis Edward Cobbold's visit to the engine house of the Old Colchester Brewery at the early age of seven.

The main reason for the visit was the coldness of the east wind and the warmth of the air coming out through the open door. Once they arrived, however, the great attraction was the gleaming engine flywheel turning at high speed. For several moments Francis stood still and silent and partly hypnotised by the revolving metal. Then a strong draught of air blew through a second door, and whisked the ends of the scarf wound about his neck against the lynch pin of the wheel. To the child, time ceased to be. He watched the woollen strands revolving with the wheel shaft, saw how they were twisted round and round like the strands of a rope, and he saw how the rope of his scarf tautened, grew rapidly shorter and then began to drag him towards the wheel. There would have been no subsequent career to record if the engineer in charge had not come in at that moment, sprang to the boy's side and, with superhuman strength, torn the scarf away from the ponderous revolving mass of metal.

In 1860, when Mr Arthur Cobbold and his family were living near the little village of Waldringfield, ten miles from Ipswich, Francis attended a dame's school. From there he went on to an Academy kept by Mr Frost and his sister at Colchester and, at the age of eleven, he joined his brother Fred at Colchester Grammar School, which at that time was run by Doctor Wright, DCD assisted by Doctor Bates (the Classics Master), Mr Harrison (the English Master), Herr Gunst (the German Master), Sergeant Atkins, who instructed the pupils in drill, and Mr Callaghan, the gymnastic instructor.

If the two learned Doctors despaired of Francis Cobbold, their state of mind was not shared by either Callaghan or Atkins. These men were concerned only with young Cobbold's physique, not his mental development. They saw, with the vision of experts, the physical man the child was destined to become, and they delighted - when the Doctors frowned - in moulding the boy's muscles, hardening his body with constant exercises, training it to accept hardship without complaint - precisely as though they knew in advance the demands that life was to make of him.

Though mentally alert, the boy was not quick to learn from books. Like many other boys, learning did not appeal to him because he could not understand - and no-one took the trouble to explain - how application to study can exercise the mind and make it easier to grapple with life's inevitable problems. Loving most branches of field sports - he won the quarter mile race and the gymnastic trophy for boys under fifteen - nonetheless he still managed to assimilate a sound education which was to be of use to him in understanding, appreciating and adapting himself to the tremendous changes he was to witness, and in which he was to play a large part.

Though familiarity with Latin, Ovid and Virgil may not teach a man to bake a loaf of baking powder bread successfully in the hot ashes of a camp fire, it will still assist in building up a comfortable philosophy cheerfully to accept a blackened loaf, in the centre of which the flour and the water still remain a glutinous mass!

The smell of tar, of canvas and of salt water had an inevitable effect on the growing boy. The sea called softly and insistently, and it was to the sea that Francis Cobbold turned in holiday freedom. The holidays were spent among the fishermen on Mersea Island, when golden days were lived on the smacks at sea; or on the river Deben, near Waldringfield, where the family possessed a sailing boat in which cruises were undertaken to Felixstowe and up river to Woodbridge; or on yachting cruises in Mr Cobbold's cutter-rigged boats, the Stag and the Dewdrop which were kept at Harwich.

The house at Waldringfield was situated on the riverbank, and in winter it was often used as a shooting box for wildfowl. Mr Cobbold was a keen sportsman, who inculcated in his sons the intelligent use of firearms, and created in them an intense interest in the wildlife found on and in the vicinity of the river.

Waldringfield on the River Deben from 'The Maybush', October 1995 (a favourite haunt of Giles, the famous British cartoonist)

A powerful telescope set up in a top room was used to mark the arrival and landing on the marshes of flighting wild- fowl, and expeditions were taken in the flat-bottom duck punts in which the boys were trained in the craft of stalking ducks - pushing the punts gently and soundlessly through the narrow water-passages among the tall reeds, or hugging the low bank of a mud flat to gain position within gun range.

Sometimes their father took the boys over the surrounding fields and sea-flats, Mr Cobbold carrying the twin barrelled 'Joe Manton' he used so expertly, seldom failing to bring down the zigzagging, darting snipe rising from the sedges. In those days the custom of driving birds was not practised; intelligent pointer dogs being used to 'put up' a covey of partridges, and the liver-and-white Clumber spaniels to retrieve the wild-fowl.

In this way, the boys were taught not only to exercise their mental powers in combating the cunning of birds - especially the alert ducks - but also to cultivate the virtues of patience and pertinacity. Their powers of observation were trained, their minds were widened, and tolerance and goodwill were established in their characters.

If the snow lay thickly on the ground, the hunters donned old white suits and hats, the colour harmonising with the background and making them difficult to be seen by the watchful and suspicious birds. When the Joe Manton was replaced by a more modern pin-fire action type of weapon, the boys accepted it with admiration, and increased their proficiency with its use.

The atmosphere of the sea and foreign countries breathed by Francis, together with occasional visits to his grandfather's ships at Ipswich, definitely planted in his soul the restless urge epitomized by the travels of Ulysses. As his mind and body grew, so did his ambition to go striding across the world.

At first perplexed by this urge, not understanding it and yet spiritually delighting in it, he read Marryat's novels with engrossed interest. He came to know ever more clearly what he wanted to do, what he wanted to be - he wanted to own and sail his own ship through the Southern Seas which had called and had claimed his eldest brother.

On making known this ambition to his parents, he received a severe check. Poignant memories of the fate of her firstborn naturally caused Mrs Cobbold to rebel against the idea. The sea had claimed one of her children: it should not claim another. Mr Cobbold tried to dissuade his son from following such a course, and with much earnestness he painted in vivid colours several careers having greater promise.

Yet the sea was too strong for even this powerful combination, and in the end his parents came to understand the strength of their son's determination to go to sea. They recognised that his ambition was not just obstinate opposition to their wishes but something entirely beyond human control, so they surrendered. At the tender age of fourteen, Francis joined the Ann Duthie as an apprentice. She was a full-rigged clipper built at Aberdeen, was owned by Messrs Duthie, and was engaged in the ever-increasing Australian trade.

It was this ship that cut the knot binding Francis Cobbold to comfort, security and an assured future. It carried him away to a life of strenuous endeavour and no little danger for which, quite unconsciously, his school drill and sports teachers and even his own father had prepared him so well.

Arthur James Cobbold Elliston was the eldest child of Arthur Thomas Cobbold and Sarah Elliston but chose to retain his mother's surname. According to his son Edgar: "…when finished his education [he] entered clerical and office work, it did not appeal to him so he went to sea in the grandfather's sailing ships, later he qualified as 1st Mate. He then went on voyages with cargoes to Baltic Ports, then to the St. Lawrence river Canada, China, Australian ports.'

'He was buffeted for three weeks around Cape Horn before they got a favourable wind. One voyage was to Melbourne, then to Dunedin. Hearing of the gold rush, he left the sailing ship and went to the Otago gold rush where he stayed a while, later moving up to Christchurch where there were a large party of Diggers going around to Hokitika in the ship 'City of Dunedin'. He was asked to go with the party but declined, saying he was tired of the sea and would go overland. The 'City of Dunedin' has not been heard of from that day to this."

Though his parents may have thought they had lost him, Arthur remained in touch with some of his family through his sister Sarah, who had moved to Melbourne. During the influenza epidemic in 1918, Arthur James Elliston worked tirelessly helping to stop the spread of what he termed 'the plague'. Ultimately, however, he caught the virus himself and died on 24th July 1919 in Reefton, New Zealand, aged 79. At his funeral all business houses and public buildings flew their flags at half-mast as a tribute to '… an Esteemed Pioneer's passing on.'