Читать книгу Ryszard Kapuscinski - Artur Domoslawski - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

Inspired by Poetry, Storming Heaven

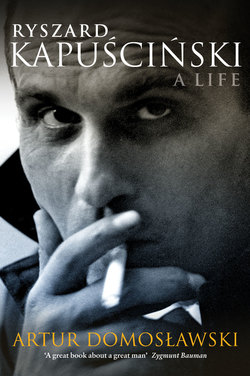

Although this photograph is undated, it was certainly taken no earlier than September 1948 and no later than the spring of 1950, outside the Polytechnic building in central Warsaw. It shows four friends from the Staszic High School: the one with the biggest shock of hair is Andrzej Czcibor-Piotrowski, and the one on the right, standing up straight and smiling, is Rysiek Kapuściński.

September 1948 was their first encounter. The pre-war Staszic High School building on Noakowski Street had not yet been reconstructed following war damage, so the Staszic boys are being put up at the Słowacki High School for girls on Wawelska Street. Here the window panes have already been replaced, but not all the floors are finished. In the gym, the pupils exercise on compressed clay.

For those of us born circa 1930 in the deep, poor Polish provinces, in the countryside or in small towns, in peasant or impoverished gentry families, the period immediately following the war was characterized above all by a very low level of knowledge, a complete lack of wide reading or familiarity with literature, history and the world, a complete lack of good manners (my pitifully miserable reading matter in those years: A History of the Yellow Poulaine, by Antonina Domańska, published in 1913, or Memoirs of a Sky-Blue Uniform, by Wiktor Gomulicki, published in 1906). Earlier, during the occupation years, either we were not allowed to read or there simply wasn’t anything to read.

In our class at the Staszic High School we had one old, torn copy of a pre-war history textbook. At the start of the lesson the teacher, Mr Markowski, would tell our classmate, a boy called Kubiak, to read out an extract from this book, and then he would ask us questions. The point was for us to retell in our own words what had just been read out . . .

So we were still victims of the war, even though its sinister noises had long since fallen silent, and grass had grown over the trenches. Because limiting the concept of a ‘war victim’ to those killed and wounded does not exhaust the actual list of losses that society incurs. For how much destruction there is in culture, how badly our consciousness is devastated, how impoverished and wasted our intellectual life! And that affects a series of generations for long years afterwards.1

Andrzej Czcibor-Piotrowski reads this extract from his school friend’s memoirs and shakes his head.

‘Is there something wrong?’ I ask.

‘This is literary self-creation.’

‘Meaning?’

‘Rysiek was very well read, but towards the end of his life he emphasized the things he lacked in those days purely to show what a long road he had travelled. It was long, that’s a fact. But the story about the only two books he had read makes it much longer, doesn’t it?’ says his friend from high-school days, smiling.

In the renovated Staszic High School building, boys and girls studied together for the first time – co-education.

‘Oh, what a lovely, chocolaty boy he was, with dark eyes and thick, dark hair,’ his classmate Teresa Lechowska (years later a translator of Chinese literature) says of Rysiek.

The ‘chocolaty boy’ sits at a desk right behind Piotrowski. They soon find a common language: poetry. Two other fellow lovers of the arts, Janek Mazur and Krzysiek Dębowski, later to graduate from the Academy of Fine Arts as a graphic designer, complete the gang.

They are teenagers – hungry for each other’s company, conversations, antics, and just being together. To spend as much time with each other as they can, they meet up half an hour before classes. They sit on the desk tops, smoke cigarettes and chat about everything, most of all about poetry. They sing. Kapuściński taps out the beat on the teacher’s chair and, with the ardour he later applied to everything he did in life, sings Lermontov’s poem about Queen Tamara, set to a tune:

In that tower tall and narrow,

Tsarina Tamara did dwell:

As fair as an angel in heaven,

As sly as the devil in hell.

His friends sing along, and when they lose the thread, Rysiek prompts them with the first lines of the verses they have forgotten. They go on wailing until the bell rings for the first lesson. At the end of the school day, they drop in at the Finnish cottage on Wawelska Street where the Kapuścińskis live, very nearby.

Just after the liberation, the family had to cram into one small room next to the construction materials warehouse which Józef Kapuściński was running. When the rebuilding of Warsaw got underway, and the Finns started sending prefabricated cottages for the capital’s builders, the Kapuścińskis were allotted one. Barbara recalls that after the misery of living in a virtual rabbit hutch, the two-family Finnish cottage seemed palatial: there was a small living room with an alcove, a kitchen, and a lavatory, as well as a little garden where their father planted vegetables, flowers and fruit trees.

When Rysiek’s parents are out, the Finnish cottage is a fine place for the high school boys’ first carousals. They crack open a bottle of vodka – a quarter litre of ‘red label’ (the cheapest kind, as they haven’t the money for anything better) – and play bridge. The empty bottles end up in a small attic space above the lavatory. Rysiek’s friends are all the more willing to come by because several of them have taken a fancy to his younger sister (‘Oh, that Basia, what a beauty she was!’).

Rysiek is popular with the girls. One of his schoolmates is madly in love with him, but he is in love with her younger sister. This is the time of first loves and conquests. The boys show off in front of each other. One has the following experience:

One day the boy turns up at a friend’s house, slightly embarrassed, but at the same time proud of a conquest. ‘Listen,’ he says, ‘she’s in the family way. Could you possibly help?’ The friend’s aunt is a gynaecologist with a private surgery on Słupecka Street. The friend writes her a note: ‘Dearest Auntie Niusia, I’m sending a girlfriend of mine to see you.’ The aunt doesn’t actually know who got the girl into trouble but feels certain it was her nephew.

Meanwhile, the real troublemaker is not at all perturbed by what has happened. He has been boyishly reckless. The others rather envy him – not for what has happened, but for the fact that he has already experienced something that still lies ahead for them. As for Rysiek, one school friend remembers that he loved boasting about girls.

Unlike the high times at the Kapuścińskis’, at Czcibor-Piotrowski’s home on Filtrowa Street there is no drinking. The friends sit politely at table, listening to the maths coaching given them by the host’s brother, Ireneusz. But they have no passion for maths – their thoughts and imaginations have flown to a very different realm. All thanks to the Polish teacher, Witold Berezecki. He has infected them with a love of literature, poetry. He’s given them the weekly Odrodzenie (Renaissance) and other cultural periodicals to read at home. Czcibor-Piotrowski remembers one occasion when the homework was to write a sonnet.

Staszic is a remarkable school; until 1950, when they take their school-leaving exams, the most highly qualified pre-war teachers will still be teaching here. Lectures on Latin are given by a female professor from Warsaw University. ‘In the humanities class’, notes Andrzej Wyrobisz, who was at the top of the class then and is now a retired professor of history at Warsaw University, ‘we were taught to “think mathematically”; in history lessons no one ever asked about dates, but about why and where from. You won’t find any dates in Kapuściński’s books either.’

A telling story from Teresa Lechowska: ‘The Polish teacher was discussing our homework and called on Kapusta [cabbage], as we used to call Rysiek, to read his aloud. It turned out to be a poem! A bit socialist–realist, a bit lyrical. I remember there was something about a mason who builds a window, which is a frame for the sky. I was surprised Kapusta had revealed a talent for poetry, because I associated him with nothing but football, which he was totally mad about.’

With Berezecki, the pupils discuss books they have discovered outside the classroom. Each one wants to show off how much he has read beyond the required minimum – that is how they impress each other. Many book collections were destroyed during the war, but a fair number have survived – the library on Koszykowa Street, for example. The Staszic pupils make use of lending libraries which are spontaneously appearing on the streets and in private flats. The young men with literary aspirations organize a school literary circle, run by Czcibor-Piotrowski. They invite well-known writers and critics to discuss literature.

Kapuściński and Czcibor-Piotrowski are crazy about the French poets. They manage to get hold of An Anthology of Modern French Verse, translated by Adam Ważyk. They know most of the poems by heart and recite them aloud. Rysiek declaims the first verse, Andrzej adds the second, and so on.

‘Once we were chatting about Paris in the 1870s and someone mentioned the “revolt of Parisians storming heaven,” ’ recalls Czcibor-Piotrowski. ‘Rysiek was planning to write a story about Rimbaud and Verlaine, about their journey from the countryside to the city to stand on the barricades of the Commune.’

The two boys also recite Pushkin and Lermontov, Yesenin and Mayakovsky. Both being from the eastern borderlands, they can read Russian in the original. As Czcibor-Piotrowski tells me: ‘I remember how one day Rysiek came to see me, clearly excited. At the Czechoslovak Information Centre he had got hold of a volume of poems by František Halas. This poet’s verse, though actually he didn’t understand much, almost nothing, made a huge impression on him – the metre, the richness of the language . . . He quoted me something from memory and suddenly stopped on the word koralka, which he associated with the Polish word koralik, a coral bead. Years later, when I became a Czech scholar and translator of Halas’s poetry, I found out that koralka simply means the same as our Polish gorzalka – homemade hooch.’

Rysiek, predictably, makes his own first attempts at poetry and sends his work to Odrodzenie and also to Dziś i Jutro (Today and Tomorrow), a journal issued by PAX, the Catholic association licensed by the PZPR. In August 1949 this journal publishes two of his poems, ‘Written by Speed’ and ‘The Healing’. His friends, the high school literati, are secretly jealous that Rysiek is the first to enter the literary world.Years later he will say, ‘I sent them off half-heartedly, just as an experiment.’

Into the city, where joy lay buried under bricks,

Feeling thorn-sharp sorrow came

a man.

His eyes saw tortured ruins burned to sticks,

His hands shot through with pain were portents of

a plan . . .

And now the streets are paved in sunshine bright

And high among the trees rise red-tiled roofs.

As stars roam through the shallow dark

of night,

People are taller than houses. For in them grows

the Truth.2

Does the sixteen- or seventeen-year-old high school student fully understand what is happening in the country? He knows there was a different political system before the war, and that now Poland is to be socialist; that the former enemy – the Soviet Union – is now a ‘fraternal country’. Does he grasp what it all means?

At the beginning of Rysiek’s high school days, the socialist revolution which is starting to occur in Poland still lies beyond the horizon of interests of the boy from ‘the deep and indigent Polish provinces’, from the ‘impoverished gentry’. It is also doubtful whether he perceives a connection between the new order and his own chances in life.

Indeed, he does join the communist youth organization, the Union of Polish Youth (ZMP), but this is not a conscious ideological choice. Whole classes and schools were enrolled in the union collectively, without asking the young people if they wanted to join. Religious instruction was still given at state schools, and sometimes the pupils went straight from a lesson in religion to a ZMP meeting.

Kapuściński has described the atmosphere within the school organization several years later when, by now conscious and politically committed, he applies for acceptance into the Communist Party: ‘The attitude of group members at the time when I took on the presidency was for the most part alien to our organization. Many people had joined it for careerist reasons. At the meetings they used to play cards or do their homework, or else they didn’t turn up at all. Wanting to eradicate this behaviour, I threatened them with expulsion from the organization. That gave them a shock.’ For this reason, he submits a self-critical report, declaring that he should have been attracting his fellow pupils to the ZMP, encouraging them rather than scaring them with expulsion. Regrettably, as he admits in his hand-written curriculum vitae, he used ‘leftist methods of managing the organization’.

Deep in his soul, the recent altar boy and now freshly baked ZMP member is still experiencing his ‘religious and mystical’ phase. He offers a friend a small collection of his own poetic and prose miniatures, God Wounds with Love, the title of which he took from Verlaine. He bangs out the text on a typewriter and signs it with the publisher’s name ‘Leo’, in honour of Lwów, his friend’s hometown. An extract reads:

On Golgotha stand three crosses. The centuries weigh down on them, yet they remain strong, invincible to the power of time. Strong as the Word of God, powerful as the Will of Christ, mighty as the Truth of the Holy Spirit.3

‘We had deep metaphysical anxieties,’ recalls Czcibor-Piotrowski, to whom the religious stanzas were addressed. ‘We used to wonder what happens to us after death.’

But not for long. The spirit of the times is starting to change radically the questions posed by literature, and ‘the Truth of the Holy Spirit’ is turning into an entirely different truth, as is evident in the following extracts from a debate about poetry held at Staszic High School. These were introduced as ‘the most typical statements made by the young debaters’.4

Krzysztof Dębowski: Mayakovsky’s and Kapuściński’s poems contain a defined ideology: Marxist-Leninist ideology. That is why they are simple, understandable and conscious.

Eugeniusz Czapliński: The poetry of the twentieth century is burdened by the chaos of the capitalist world. Works that seem to talk about life are the negation of life. That is not the case in the poems cited by V. Mayakovsky and R. Kapuściński. These poems were written in the context of building socialism. A conscious ideology speaks through each poem; they address the issues of the worker and the education of socialist youth, and illustrate problems that lie within the reader’s sphere of interests.

Andrzej Piotrowski: I would like to conduct an experiment, involving the comparison of two pieces of writing: an extract from Good!, the epic poem by the great poet Vladimir Mayakovsky, and extracts from a poem called Winter Scenes – Pink Apples, by the novice poet Ryszard Kapuściński.

In Mayakovsky the theme of the poem is work, work, which is a basic element of life in socialist society. In Kapuściński we are dealing with another element – rest (children on holiday).

Kapuściński does not strongly stress his political affiliation, as Mayakovsky has done . . .

The author of Winter Scenes takes the position of an observer, a commentator. And here lies a basic error.

A second error, which highlights this comparison best of all, is Kapuściński’s use of a symbol which comes, as we know, from a totally different era, which erases the simplicity of the poem, creates appearances of insincerity and avoids calling things by their proper names. I say appearances, as I have no doubt that Kapuściński is sincerely dedicated to our common cause and knows that poetry should have a truly ideological countenance.

It is hard to judge a poet on the basis of only one of his poems. Kapuściński’s future work will give us the opportunity to examine the matter again . . . Each of us keeps repeating the comment that every creative artist learns from his mistakes. We say it all the more sincerely, as Kapuściński is our friend, and we ourselves will help him to overcome his errors through criticism of his poems.

At the end, colleague Ryszard Kapuściński read out his new poem, closer, in his view, to the correct poetic traditions.

ON OBLIGATIONS

Well, my comrades and poets,

let me say a few words to you.

For us the need is vital

to outpace the tortoise in poetry too.

. . .

Let’s not mince our words,

the matter is simple and clear:

we cannot let poetry’s cause

be left to trail in the rear.

We are lagging far behind.

But after the miners let us race.

Perhaps you can easily guess

What Mayakovsky would say in our place?

. . .

Many a man will outdo me, I know,

Outshine me with his talent’s flame,

I am not swapping the song of the lyre

for labour’s whirring just for fame.

They question Markiewka,

Poręcki, Michałek, and Markow.

They’re questioned by the workers led

by the Party.5

The socialist realist verses are Kapuściński’s first conscious ideological declaration.

Up the ‘staircase’ of Mayakovsky’s stanzas, the eighteen-year-old Rysiek enters two worlds: that of literature, and the kingdom of the New Faith.