Читать книгу Schiele - Ashley Bassie - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Foreword

ОглавлениеEgon Schiele’s work is so distinctive that it resists categorisation. Admitted to the Vienna Academy of Fine Arts at just sixteen, he was an extraordinarily precocious artist, whose consummate skill in the manipulation of line, above all, lent a taut expressivity to all his work. Profoundly convinced of his own significance as an artist, Schiele achieved more in his abruptly curtailed youth than many other artists achieved in a full lifetime.

Self-Portrait

1907

Oil on cardboard, 32.4 × 31.2 cm

Private collection

In the photograph of Schiele on his deathbed, the twenty-eight year old appears asleep, his gaunt body completely emaciated, his head resting on his bent arm; the similarity to his drawings is astounding. Because of the danger of infection, his last visitors were able to communicate with the Spanish flu-infected Schiele only by way of a mirror, which was set up on the threshold between his room and the parlour. During the same year, 1918, Schiele had designed a mausoleum for himself and his wife.

Portrait of Leopold Czihaczek, Standing

1907

Oil on canvas, 149.8 × 49.7 cm

Private collection

Did he know, he who had so often distinguished himself as a person of foresight, of his nearing death? Did his individual fate fuse collectively with the fall of the old system, that of the Habsburg Empire.

Schiele’s productive life scarcely extended beyond ten years, yet during this time he produced 334 oil paintings and 2,503 drawings (Jane Kallir, New York, 1990). He painted portraits and still-lifes land and townscapes; however, he became famous for his draftsmanship.

Village with Mountains

1907

Oil on paper, 21.7 × 28 cm

Private collection

His sketches already demonstrated an astonishing sense of observation. Schiele, like many other expressionist artists of his times, looked into the innermost psychic life of his subjects as well as his own. According to the expressionists, this introspection was the purest definition of the process of artistic creation.

A potent aspect of Expressionism was the conviction held by its creators, that their endeavours were carrying art into a wholly new realm of experience. Expressionist art could display spectacular technical innovation. However, formal, surface qualities were a means, not an end.

Landscape in Lower Austria

1907

Oil on card, 17.5 × 22.5 cm

Private collection

Expressionism aspired to give form to nothing less than a new kind of inward vision. It involved a heightened perception that appeared, to some viewers, to verge on clairvoyance. Expressionists sought an intimate, subjective, and deeply resonant communication between the artist and the viewer. Kokoschka described it as “form-giving to the experience, thus mediator and message from self to fellow human. As in love, two individuals are necessary. Expressionism does not live in an ivory tower; it calls upon a fellow being whom it awakens.”

Sunflower I

1908

Oil on carboard, 44 × 33 cm

Niederösterreichisches Landesmuseum, Vienna

Straining against the moral grip of conventions of thought, speech and behaviour inherited from the nineteenth century, Expressionism was the means by which many artists and writers tried to give free expression to the instinctively, authentically wayward psyche – to break out of the straitjacket, as it were. Sigmund Freud’s research into the unconscious and the processes of repression – whereby painful memories or unacceptable impulses are consigned to the unconscious – only appeared to confirm the existence of a powerful and conflict-ridden “inner life.”

Portrait of the Painter Anton Peschka

1909

Oil and metallic paint, 110.2 × 100 cm

Private collection

In attempting to give expression to repressed aspects of the psyche, Expressionist art, literature, theatre, dance and music therefore tended to emphasise what was unruly, violent, chaotic, ecstatic or even demonic. Eros and Thanatos, sex- and death-drives, were recurrent underlying themes. This kind of excavation of the psyche was especially marked in the radical new art that started to emerge from Austria around 1910. As Vienna’s definitive satirist Karl Kraus, put it, “form is not the dress of thought, but its flesh.”

Portrait of Gerti Schiele

1909

Oil, silver, gold-bronze paint and pencil on canvas, 139.5 × 140.5 cm

The Museum of Modern Art, New York

Purchase and partial gift of the Lauder family, New York

Thus, while Sigmund Freud exposed the repressed pleasure principles of upper-class Viennese society, which put its women into corsets and bulging gowns and granted them solely a role as future mothers, Schiele bares his models. His nude studies penetrate brutally into the privacy of his models and finally confront the viewer with his or her own sexuality.

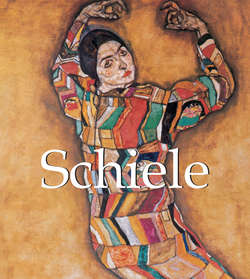

Self-Portrait with Spread Fingers

1909

Oil and metallic paint on canvas, 71.5 × 27.5 cm

Private collection, New York

The German art encyclopaedia, compiled by Thieme and Becker, described Schiele as an eroticist because Schiele’s art is an erotic portrayal of the human body. Futhermore, Schiele studied both male and female bodies. His models express an incredible freedom with respect to their own sexuality, self-love, homosexuality or voyeurism, as well as skilfully seducing the viewer. For Schiele, the clichéd ideas of feminine beauty did not interest him. He knew that the urge to look is interconnected with the mechanisms of disgust and allure. The body contains the power of sex and death within itself.

Leopold Museum, Vienna

Self-Portrait

1910

Gouache, watercolour and black pencil

44.3 × 30.6 cm