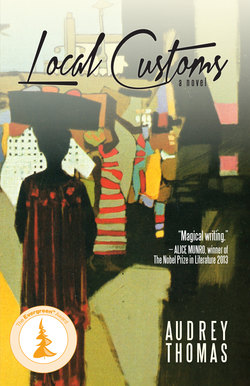

Читать книгу Local Customs - Audrey Thomas - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Letty

ОглавлениеI WAS THIRTY-FOUR when I first met George Maclean, and somewhat fearful and uncertain as to what my future was to be. Famous, yes, but solitary and I had recently noticed how some of my friends’ children called me “Aunt.” Soon those children would be having children and there would be another round of silver christening cups or porringers. Have you read Lamb’s essay about Poor Relations? Would I end up like that, an embarrassment, an elderly lady living in a pokey room at my brother’s house, his wife (I assumed he would marry now that his living was secure) treating me with condescension, his children (I assumed he would do the usual thing and have children) prompted to ask Auntie if she wanted the last tea cake or crumpet (Auntie declining even as her stomach rumbled). Or perhaps the Misses Lance would leave me their house when they slipped off their mortal coils, assuming old Mr. Lance, their brother, had already slipped his. I had a soft spot for old Mr. Lance. Whenever I was sent a gift of a brace of pheasants or a nice plump hare, he would remind us of what a crack shot he had been in his youth. The Lances did have nieces and nephews, so I probably could not really count on anything in that direction. If my brother didn’t want me, perhaps I would live out my declining years in a pokey cottage, seeing no one, alone with my books, my canary, and a cat, until, if a traveller knocked, he would be greeted only by a whisper behind a door.

I had always declared I would never marry, but that is the sort of thing women say, isn’t it, when they are no longer girls and still single. I didn’t so much want a husband as want the security of a husband, the status that comes from being married. He would have to be a gentleman, of course (the Landons may have come down a bit in the world but we were of an old and respected Hertfordshire lineage). It would also be useful if he had a good income, but even an adequate income would suffice. I had my own money — from my books — although I didn’t see a great deal of it; as soon as it came, a goodly portion went out, to my brother, for his Oxford education, and to my widowed mother. There was a sister, sickly from birth, and she lived with my mother until the poor child died at age thirteen. You will be shocked, but at the moment I can’t remember her name. An ordinary name, nothing like Letitia or Whittington, my brother. Elizabeth, yes, that was it. I was the eldest and felt it was my duty to help out, although there were days when I could have killed for a new frock. Everything I wore was always just slightly behind the latest fashion, even with the help of new ribbons or a gift-pair of new gloves. My admirers did often send me things, pheasants, for example, gloves, once an incredible rainbow-coloured silk shawl. When they sent letters without gifts I was always a little disappointed.

(“Dear Letitia, do you remember how we walked with our arms around one another when we were young?”) I suppose all famous people get letters like that, often from virtual strangers. “Dearest Letitia, I have woven you a special bookmark depicting a scene from Ethel Churchill,” some ghastly scrap that she probably spent hours stitching. Or even worse, “Dear L.E.L., or may I call you Miss Landon? I have taken the liberty of enclosing a small selection of my verse …”

They want a reply, those versifiers. “Dear Miss X, how kind you were to send me ‘A Sonnet Sequence on the Death of my Canary’…” They are hoping you will help them get published, of course, although they never come straight out and say so. I think I can safely state that never once, never once, did any of these unsolicited missives contain a spark of genius or even of good yeomanlike workmanship. The bookmarks had more craft than all these ballads or sonnet sequences or meditations in a graveyard. Can’t they tell? Ah well, we are told that love is blind and no doubt they love these things they write. If I am feeling kindly, then I do admire their courage, for it takes just as long to write a bad poem as a good one, perhaps longer, and even those of us who have been fortunate enough to have published and been praised, still tremble that next time, next time, we may be laughed at or even reviled. A horse at a mill has an easier life than an author.

And I knew my work would not be fashionable forever, for tastes in art change just as tastes in costume do. I remember going to Madame Tussaud’s Waxworks with dear Lady Blessington and she said to me, “One day your likeness will be on display,” and I replied, “Complete with my little attic room and my hoard of candle ends?” We laughed, but that night I had a terrible dream about my wax doppelgänger and a great fire in the waxworks. I saw my face melting, my dress on fire, my lips running down my chin and onto my bodice. All the others were melting, too, the kings and queens, the murderers and heroes and soon we all ran together. When the firemen arrived with their water, we had congealed into a great, many-coloured lump full of glass eyes. I woke up with the Misses Lance pounding on my door, asking if I was all right.

I had been reading Macbeth and I suppose I was thinking of “Out out, brief candle.” Who knows what ideas and images our sleeping selves can yoke together?

I have come a long way from talking about spinsterhood, but from my thirtieth year on, however gaily I presented myself to Society, my future as a single, aged woman was always there in the back of my mind. (“Do offer Auntie the last crumpet.” And Auntie, with butter dripping down her whiskery chin and death spots on the backs of her hands, gives a grateful little mew.)

In October 1836, I was staying with Matthew Forster and his family for a few days while my room at the Misses Lance was undergoing a good turnout and a new carpet was laid. My feet had been very cold the winter before, in spite of worsted stockings knitted by Miss Agatha and warm slippers donated by Miss Kate. My little coal fire did not cast the heat very far and as I had never been able to write on my lap, my poor appendages shivered beneath my desk. I often wrote far into the night, indeed sometimes until I heard the milk pails clatter and the sound of horses’ hooves in the street below. The solution, or at least a partial solution, was to have a carpet fitted. I decided I could not stand all the fuss this would entail so, leaving the Misses Lance to supervise, I threw myself on the mercy of the Forsters.

When I came down to breakfast on the second morning of my stay (I dislike breakfast, but when one is a guest it is only good manners to put in an appearance, nibble on some toast and try not to look at the gentlemen eating kidneys and sausages, cold beef and pickle), Matthew waved a sheaf of papers at me and said, “This should interest you, Letty!”

“Why would some dull report interest me?” I said, settling myself near the toast rack and marmalade.

“This is not dull; in fact, it’s exceedingly interesting, a record of an excursion to Apollonia, on the Gold Coast, where the writer faced down an insurrection by the paramount chief. Quite a feat. And he signed a treaty with the old scoundrel as well.”

“That’s nice,” I said, not terribly impressed.

“And the writer, who is governor of Cape Coast Castle, is on leave here and coming tonight to dine.”

“And what is this paragon like?”

“George? An excellent chap, one of our best. Of course you want to know if he’s handsome.”

“That’s nonsense. I am much more interested in character than physiognomy.”

“Then you must be the exception. In any event, you shall make up your own mind about him.”

I took the report up to my room and read it carefully. There were words in it which set my blood racing: danger; price on my head; stood firm; the royal umbrellas; the heat; success; Africa. This last made me shiver with excitement. Our hero’s full name was George Maclean and so I sent the maid over to Regent Street for a length of Maclean tartan. By teatime I had concocted a shawl, a sash, and even a bit of ribbon for my hair. It was not that I expected much in the way of looks — or even manners. I had seen some of these Old Coasters at Matthew’s house before: stringy men, yellowish around the eyeball, prematurely grey or white, hands a bit shaky from the remains of fever or a steady diet of drink. After I became acquainted with cockroaches out there, I had a fancy, because of the similarity of skin colouring, that these ubiquitous insects were nothing but the souls of Old Coasters.

I sat on a chair, in all my Scottish finery, and waited impatiently for George Maclean. Chatted to many of the guests — I was known for my quick wit and merry laugh — but kept an eye out for the hero of Apollonia. I must admit the idea of an Englishman getting the better of a black man out in Western Africa did not seem much of an accomplishment, but Matthew assured me it was, so I had practised looking impressed and intent in front of my looking-glass for a good half hour.