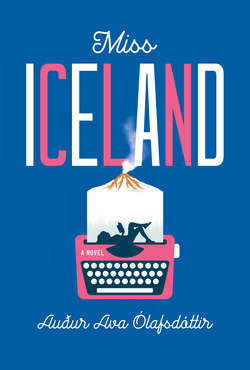

Читать книгу Miss Iceland - Audur Ava Olafsdottir - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеThe room of the one who gave birth to me

I stumbled across an eagle’s nest when I was five months pregnant with you, a two-metre rough cavity of flattened lyme-grass on the edge of a cliff by the river. Two pudgy eaglets were huddled up inside it. I was alone and an eagle circled above me and the nest. It flapped its wings heavily, one of which was tattered, but refrained from attacking. I assumed it was the female. She followed me all the way to the edge of the farm, a black shadow looming over me like a cloud that obscured the sun. I sensed the baby would be a boy and decided to name him Örn—Eagle. On the day you were born, three weeks before your time, the eagle flew over the farm again. The old vet that had come to inseminate a cow was the one who delivered you; his final official duty before retiring was to deliver a baby. When he came out of the cow shed, he took off his waders and washed his hands with a new bar of Lux soap. Then he lifted you into the air and said:

“Lux mundi.

“Light of the world.”

Although he was accustomed to allowing the female to lick its offspring unassisted, he started to fill the blood-pudding mixing tub to bathe you. I saw him roll up the sleeves of his flannel shirt and dip an elbow into the water. I watched them—the vet and your father—stoop over you with their backs to me.

“She’s her father’s daughter,” your father said. Then he added and I clearly heard him: “Welcome, Hekla dear.”

He had already decided on the name without consulting me.

“Not a volcano, not the gateway to hell,” I protested from the bed.

“These gateways have to be allowed to be somewhere on this earth,” I heard the vet say.

The men pressed together to hunch down over the tub again and took advantage of my defencelessness, my aching pain.

I didn’t know when I got married that your father was obsessed with volcanoes. He would submerge himself in books with descriptions of volcanic eruptions, correspond with three geologists, have foreboding dreams about eruptions, live in the constant hope of seeing a plume of smoke in the sky and feel the earth tremble under his feet.

“Perhaps you’d like the earth to crack open at the bottom of our field?” I asked. “For it to split in two like a woman giving birth?”

I hated lava fields. Our farmland was surrounded on all sides by thousand-year-old lava fields that had to be clambered over to go pick blueberries; you couldn’t stick a fork into a single potato patch without striking a rock.

“Arnhildur, the female eagle,” I say from under the cover that your father pulls over me. “The one who is born to wage battles. There are barely twenty eagles living in this country, Gottskálk, I add, but more than two hundred volcanoes.” That was my last card.

“I’ll make you a nice cup of coffee,” your father said. That was his compromise. He had made up his mind. I turned the other way and shut my eyes, I wanted to be left in peace.

Four and a half years after you were born, Hekla erupted after its one-hundred-and-two-year slumber. That’s when your father finally got to hear the roaring explosion he had been pining to hear in the west in the Dalir district, like the distant echo of the recently ended world war. Your brother Örn was two years old at the time. Your father immediately called his sister in the Westman Islands to find out what she could see through the kitchen window. She was frying crullers and said that a plume of volcanic smoke hovered over the island, that the sun was red and that it was raining ash.

He covered the mouthpiece and repeated every single sentence to me.

“She says that the sun is red and it’s raining ash and that it’s as dark as night and she had to turn the lights on.”

He wanted to know if it was a spectacular and daunting sight and if the floor was shaking.

“She says it’s a spectacular and daunting sight and that all the drainpipes are full of ash and that her husband, the boat mechanic, is up on a ladder trying to unclog them.”

He lay with his ear glued to the radio and gave me the highlights.

“They say that the mouth of the volcano, the crater, is shaped like a heart, a heart of flames.” Or he said: “Steinthóra, did you know that one of the lava bombs was eleven metres long and five metres wide and shaped like a cigar?”

Eventually he could no longer satisfy himself with his sister’s descriptions of the views from her kitchen window or the frozen black-and-white photographs of the giant pillar of smoke on the front page of the Tíminn newspaper. He longed to see the eruption with his own eyes, he wanted to see colours, he wanted to see glowing blocks of lava, whole boulders shooting into the air, he wanted to see the red fiery eyes spitting shooting stars like sparks in a foundry, he wanted to see a black lava wall crawling forward like an illuminated metropolis, he wanted to know if the flames of the volcano turned the sky pink, he wanted to feel the heat on his eyelids, he wanted his eyes to tingle, he wanted to charge down south to Thjórsárdalur in his Russian jeep.

And he wanted to take you with him.

“Jónas Hallgrímsson, our national poet, who produced the best alliterations and poetry about volcanoes ever written, never witnessed an eruption,” he said. “Neither did the naturalist Eggert Ólafsson. Hekla can’t miss seeing her namesake erupting.”

“Why don’t you just sell the farm and move down south to become a farmer in Thjórsárdalur instead?” I asked. I could just as easily have asked: “Don’t you want to move from the land of Laxdæla Saga to the Land of Njál’s Saga?”

He sat you on a cushion on the passenger seat of the jeep so that you could see the view, and I was left behind with your brother Örn to take care of the farm. When he returned with melted soles on his boots, I knew he had gone too close.

“The old dear’s arteries are still bubbling,” he said, and carried you to bed, sleeping in his arms.

In the summer, ash reached us in the west in Dalir and destroyed the fields.

Dead animals were found in troughs where gas puddles had formed: foxes, birds and sheep. Then your father finally stopped talking about volcanoes and went back to farming. You, however, had changed. You had been on a journey. You spoke differently. You spoke in volcanic language and used words like sublime, magnificent and ginormous. You had discovered the world above and looked up at the sky. You started to disappear and we found you out in the fields, where you lay observing the clouds; in the winter, we found you out on a mound of snow, contemplating the stars.