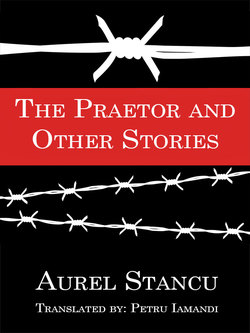

Читать книгу The Praetor and Other Stories - Aurel Stancu - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTHE PHOTO ON THE DESK

They carried a stiff upper lip for three days, turning down every invitation, pretending they didn’t get any hint, and making fun of the judges’ and local authorities’ almost desperate attempts to corrupt them in one way or another, or to tempt them with a special meal in the hope that they would soften their hearts. The two inspectors, representing the Court of Appeal, with three counties under their jurisdiction, were checking up the Municipal Court following a more or less serious complaint.

At the age of fifty-five they had a long career behind them, being real celebrities in their trade. They were an odd couple: one was the scourge of court rooms, cold, impenetrable, and ruthless; the other sluggish, ironic, sometimes lenient, and with a bent for rather listening than talking.

Jean Gulerez was the sort of magistrate who considered Justice blind, deaf and dumb, the only holder of truth. Unlike him, Vasile Lazar believed that there was always room for interpretation, that every law had its unseen side which could be put to good use. Both of them settled their cases in the same office for no other judge would have enjoyed working in Jean Gulerez’s presence. Not that Vasile Lazar hadn’t needed quite a few years to discover his colleague’s true nature, other than being a low-spirited man, grumpy, always frowning, and never willing to give in.

Gulerez was a penologist, Lazar a common law judge. The penologist was hardly an attractive man, with one leg shorter than the other, and a squint. Though quite short, the common law judge was very likeable, wore a big beard, and women fell for him in a big way. To Gulerez, women were of no substance, he considered them all treacherous and interested. Vasile Lazar picked them carefully, often saying that for a mug of milk one didn’t have to buy a cow.

Under the circumstances, the fact that the couple was inspecting a court was frightening, the agitation in the town verging on paranoia. The couple’s reputation was strengthened now, after three days of inspection—except for the odd cup of coffee, they had turned down everything else. On the fourth day, however, the tension faded away and a general relief, like a cool summer breeze, flooded the court. The inspectors had accepted the invitation of Viorel Opris, chairman of the County Council, to have dinner at a motel about two miles from the town, on the road to the capital.

“They’ve got an excellent chef there, his venison is a wonder! It’d be a shame to miss such an opportunity, the more so as the chef’s going to leave the place soon. He’s going to work in a big restaurant in Italy, you know,” the chairman overdid it.

“Ah, venison,” Vasile Lazar exclaimed, laughing up his sleeve.

“Deer, boar?” Jean Gulerez looked interested, to the local official’s surprise.

“Everything, even bear paw stew! As a matter of fact, that’s the specialty of the house.”

They left the court in the chairman’s car. So as untouchable they had seemed while checking everything up, placing law before everything else, as human they proved to be during the meal. They enjoyed the food, the drinks, and the smutty jokes. It was an evening beyond expectation, a real feast.

In the almost empty restaurant, at a remote table, there were other important people, at least that was what the attention the staff were paying to them gave everyone else to understand. The two groups ignored each other, although the chairman commuted between the two tables. The judges were not curious to know who those people were, one thing that couldn’t be said about the other group, intrigued by the staff acting so obligingly and by their rivals not minding them.

After having several glasses, flushed with wine, Jean Gulerez felt the need to go to the toilette. He stood up, a little unsteady, and instead of heading for the gents’, he opened the first door he bumped into and found himself on the balcony.

“Hey, asshole, that’s the balcony, the john’s in the opposite direction,” shouted one of the people at the other table to the others’ roars of laughter.

Gulerez had never been insulted like that before. He turned around red with anger and said:

“Look who’s talking! A beast’s asshole! Why do you care where I want to go or what doors I open?”

“Watch your mouth, you, mutant, or I’ll measure your length on the floor!”

“Well, if I’m a mutant, you’re a bloody drinking mutant!”

The chairman jumped between them. Choking with embarrassment, he tried to settle the conflict.

“Gentlemen, please, don’t forget you’re public figures, you’re in high positions, you aren’t supposed to make a rumpus in such a place!”

Too late. The two men broke loose, swearing at and threatening each other. It took the chairman quite a while to calm them down. When the judge returned from the toilette, Viorel Opris came to his table together with the man who had aggressed him verbally.

“I think I should introduce you to each other, after all. This is Judge Jean Gulerez, inspecting our county. This is—”

“Ion Cristian, the county Prefect.”

Both parties were taken aback. The judges hadn’t expected the boor to be such a high official. Jean Gulerez came down a peg and shook the prefect’s hand.

Everyone sighed with relief when the prefect sat down at the judges’ table. He was a stout man, a little bit overweight, russet- to fair-haired or the other way round, a man who breathed out prosperity.

“Gentlemen, it just happens when you’ve had a glass too many! I apologize for the coarse language. Since it was I who started it, I’d like to be the one to end it.”

“I admit I overdid it too,” said Jean Gulerez.

“It must have been the bear paw, I’ve never tasted anything like that before,” his colleague tried to make a joke.

Everyone burst out laughing and the feast went on. They sat together at the same table for about two hours and all this time they emptied three bottles of red wine and one of white wine, and ate boar salami and deer stake. The only thing they missed was a fiddler to stir up their feelings and mix them with liquid nostalgia.

Suddenly, Ion Cristian stopped eating, gazed at the people around him and said in a morose hoarse voice:

“Listen up, you, assholes, do you know who I am?” Then he scanned solemnly, “I am the Prefect, number one in the county, I represent the Government. And who the hell are you? Some old farting judges, inspectors today, nothing tomorrow, but I, I can be a minister any time!”

The air froze instantly. The magistrates looked at each other trying to grasp what was happening and if it was worth answering a man who had already swallowed several bottles of red and white wine, a mixture which would have finished anyone.

“My dear Prefect, I may have exaggerated things a little bit, but now that we’ve known each other I can’t see why we should resume fighting,” replied Jean Gulerez in an incredibly calm manner.

“Since when have we known each other, you, bloody scroungers, coming here for a free meal! So you’re inspectors, are you? If you are what you claim to be, why don’t you pay for the meal? You look like criminals to me, not judges! I think I should have you arrested!”

The chairman winced as if lashed and tried for the second time to calm things down. No way. Offended, the judges stood up and headed for the door. Behind them the prefect howled like a wild beast:

“Me apologize to those criminals?! I’d better call the Ministry of Justice! You’ll just have to walk to your hotel! Walk, do you hear me? No free ride! I’m the authority here and you are the disgrace of Justice! And don’t let me see you in my town again!”

Vasile Lazar had experienced a similar scene, maybe a tougher one, ten years before. Staying at a hotel in Brasov, he had gone down to the receptionist’s around midnight and asked the receptionist to have the heat turned up, it was too cold in his room. At the desk there was a drunken police captain who was whiling away his time gazing at the receptionist’s generously exposed breasts. The policeman felt a sort of call-up in him, like males do when in heat. “What’s up, jerk? Do you feel like getting wacked a little?” Dumbfounded, the judge answered, “I just want more heat in my room and I’ve got nothing to talk to you about.” “So you’ve got nothing to talk to me about. Do you know who I am?” “I don’t know who you are. I just know you’re drunk and since you’re wearing your uniform probably on duty. Which is not exactly in accordance with the rules.” “Ah, you want me to apply the rules, don’t you? All right, scrounger, here’re the rules!” And before Lazar realizing it, the policeman raised his truncheon and hit him on the back. There followed other blows. “Stop it, I’m a judge, stop it, I’m a judge!” It was very hard for the receptionist to stop the policeman, who had somewhat got tired, and then take Vasile Lazar to his room.

The next day at about noon, bent by the blows, Vasile Lazar was listening in the court president’s office to the policeman serenely apologizing to him. It wasn’t the words that mattered, it was the way in which they were being uttered—the beast was using humble words offensively. Something like, “I’m sorry, it just happened, I couldn’t help it.”

His own experience embittered Vasile Lazar and urged him to persuade Jean Gulerez to walk to the town, though the latter rather dragged his left foot. But after a few hundred feet a taxi, which Viorel Opris must have called, caught up with them and took them to the hotel in a state bordering on hysteria.

* * * *

Two years later, Jean Gulerez fell ill. One day he felt a pain in his right side and, for the first time in his life, was taken to hospital. A week of tests and the diagnosis fell like a guillotine: widespread cancer. The judge whom no law paragraph had bent, no tear of regret had softened, no family, no acquaintance had puzzled out, a man who had been a demon for work on thick obscure files, a man who had had a meal in a restaurant every two years and had only one friend, Vasile Lazar, received the news of his imminent final departure with peace. “Pity, there’re still some things to do.” Then he started the preparations, getting good jobs for his children and, again for the first time in his life, pulling a few strings to get a house from the Town Hall for his daughter.

Three months later he died. His photo remained on his desk for a long time, several years in fact, no one wanting to replace him in that space. Every morning, before entering the court room, his friend lit the votive light next to his photo. And from it Jean Gulerez smiled as gravely as he had done when he was around.

Judge Vasile Lazar, who no longer did any inspection work, lived a few blocks away from the court so he usually went back to his office late in the afternoon. One day a file leapt to the eye. A name which went to and fro in his mind for a while made him start: Ion Cristian. The file had reached the Court of Appeal, after the Court of Law had sentenced Cristian to a year’s imprisonment and the pay of a large amount of money as civil damages for misuse of authority. “Who the hell is this Ion Cristian?” After some time, leaning against the back of his armchair, he remembered the scene at the restaurant. “Jean, it’s time for revenge! The big political buffalo is in my hand!” From his photo Jean Gulerez was staring ruthlessly at the file.

Ion Cristian’s fate was to be decided by Vasile Lazar and the latter had only to confirm what the other instances had decided. He would be covered by two judicial decisions, which would place him above any suspicion. Besides, he owed it to his dead friend. He took the file with great satisfaction and put it on top of the others, without examining it, just to finish it the next day. That night, Vasile Lazar saw Jean laughing in his dream, a thing that happened very rarely when he was alive.

He had barely got up in the morning when the phone rang:

“Hello, this is Viorel Opris speaking.”

“Ah, Mr. Opris, the Chairman, I’m so delighted to hear you. How are you? Any special meal coming your way? Any venison?”

“It is, Judge, any time, but right now I’m calling you about something very urgent. Do you remember the former Prefect, Ion Cristian? A crook who’s left wide tracks of pain behind him, a boor who thought himself immortal…well, he’s in the same party with me. He’s got a file on your desk. You’re his last chance.”

“And what would you like me to do, repeal the sentence? Isn’t this phone call of yours a kind of intrusion in Justice’s affairs, I wonder.”

“No, far from it, Judge,” the chairman changed his tune. “I know you too well. I’m just asking you to examine the file carefully and do justice. That is, please, don’t let yourself be influenced by the other decisions. Indeed, this man’s trampled a whole county under foot but now some of his enemies have settled accounts with him. And I don’t think we should be as evil as they are.”

“The file is foolproof, mister! All I can do is go through it and try to forget what happened then.”

A few hours later, Ion Cristian, his face like wrung-out linen, knocked on the judge’s door. The judge let him in, boiling inside.

“Come in and please be short, my time is precious.”

“I’m innocent, Judge! They’ve made mincemeat of me just to take revenge on me.… They’re ruining me, you must realize that.… Help me, please!”

“So I’m no longer a criminal? I no longer look like a scoundrel?”

The former prefect answered hysterically:

“Listen, Judge, I’ll give a fabulous party, I promise, with girls, lots of crazy girls, with breasts this big…easy to please, I swear.… At a chalet hidden in the mountains, or maybe you want something else.…”

“Get out of my office! Out! I’m finished with you!”

Cristian kept begging:

“You are my last chance, Judge, I know I was a jerk, but help me, please!”

“I said I’m finished with you!”

“You’re killing me, Judge.”

“You’ve been killing yourself God knows for how long.”

Ion Cristian left like a dog beaten up by its master. There was no chance for him in that office. There had never been, in fact. To Vasile Lazar he was a bastard. No way for him to be judged as an ordinary bastard but as a special one.

The judge read the file of the former prefect several afternoons, page by page. Then he passed the final sentence.…

* * * *

It was Friday, about ten o’clock in the morning, when Ion Cristian tried to talk to Vasile Lazar for the last time.

“Go away from my door! I don’t want to see you again! I’ve already passed the sentence. Go and ask the clerk to read it to you. And don’t you dare knock on my door again!”

The former prefect felt his last hope had died. He thought of his future and saw it like a ship sinking off the coast, under the eyes of those standing on the shore. He rushed to the clerk’s office to hear the sentence he already knew. And he stood still: he had been cleared of all charges.

Vasile Lazar locked himself in asking not to be disturbed. Sitting down in his armchair he stared at the photo of his former colleague. “Dear friend, I couldn’t help it, that jerk is innocent! If you can imagine that.… He was right. You would have done the same, I’m sure.…”

In the photo there was a seasonless rain falling from Jean Gulerez’s eyes.