Читать книгу Lamia's Winter-Quarters (Alfred Austin) - with the original illustrations - (Literary Thoughts Edition) - Austin Alfred - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

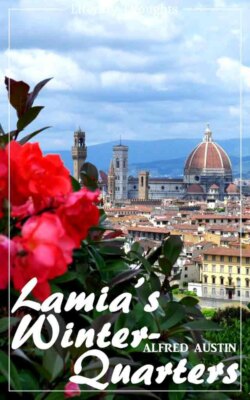

‘I observe,’ said Lamia, ‘that another of those somewhat numerous prose performances of yours, that are more or less remotely connected with Gardens, and which you were pleased, without any previous consultation with me, to entitle Lamia’s Winter-Quarters, is, like the first of the series, The Garden That I Love, to be issued in an equally luxurious form, and to be illustrated by the attractive talent of Mr. Elgood. But since this project, to which my attention was called by that now universal source of information, advertisements, has been alluded to, do you mind telling me why you called our delightful sojourn in a Tuscan villa overlooking Florence my winter-quarters rather than the Poet’s winter-quarters, or Veronica’s, or, for that matter, even yours?‘

Somewhat embarrassed, I replied:

‘To have called the book my winter-quarters would have savoured of egotism, and would, moreover, I fear, have failed in attractiveness.’

‘But against Veronica’s name, or the Poet’s, no such objection would lie?‘

‘Perhaps not,’ I said. ‘But possibly from living with them, to say nothing of you, I have acquired a habit of respect for the fact; and it was more consonant with truth to call the winter-quarters yours.’

‘How is that?’ she asked.

‘Well, you see, Veronica does what the Poet wishes, and the Poet does what you wish, and so——’

‘I beg to say,’ she interrupted, ‘that is not the fact. I do what the Poet wishes.’

‘Is not that much the same thing?’ I replied. ‘You always seem to have the same wish about everything. So I suppose you felt precisely as he did when he wrote those adulatory lines which I saw in the public prints, a few days ago, under the heading, “A Poetical Impromptu.”‘

‘Really! He wrote no such, nor indeed any, lines, never having seen nor heard of the lady in question, in his life.’

‘Is it possible?‘ ‘Everything of that kind is possible in these days.’

‘But did he not contradict it?‘ ‘Did he contradict! Like a good many other men, he would have to keep a Secretary for no other purpose than to contradict what is reported in the papers, and most of which they probably never see. I should think he turned the opportunity to better account by recalling a couplet of Pope—

‘Let Dennis charge all Grub Street on my quill,

I wished the man a dinner, and sate still.’

‘But,’ I said, ‘are not such inventions calculated to injure the influence of the prints that resort to them?’

‘I should think so,’ she said, honouring me for once by talking seriously. ‘But whose, and what, influence is not being injured just now by their own misdoings? The House of Commons, for instance, though more written and talked about than ever, has long been losing influence, and the Press is now following suit; and it is the silent, or comparatively silent, persons and forces that are acquiring or increasing influence; the Monarchy, the House of Lords, and——’

‘The House of Lords!’ I exclaimed. ‘I thought it was going to be abolished, or to have its very moderate claims yet further curtailed.’

‘Did you?’ she answered. ‘Then your thoughts are not of much value. I daresay it would be difficult to persuade Politicians that Shakespeare was wiser than all the sons of the Mother of Parliaments put together; and what does he say?

‘Take but degree away, untune that string,

And mark what discord follows.

And so long as the British nation continues on the whole to be sane, it will never consent to take “degree” away, in order to fasten on itself a dead level and a tyrannical uniformity.‘

I was so flattered by Lamia having, in a short space of time, condescended to talk seriously with me, that I thought a favourable opportunity had arisen for preferring any request that I wanted her to grant. Encouraged by this feeling, I ventured to say:

‘A great adornment and advantage to the forthcoming volume would be a portrait of the person whose name is associated with it; in other words, a portrait of Lamia.’

‘So it has come to that!’ she replied. ‘Not satisfied with having travestied me in—let me see—yes, one, two, three, four, five successive volumes, The Garden That I Love, In Veronica’s Garden, Lamia’s Winter-Quarters, Haunts of Ancient Peace, and The Poet’s Diary, you now propose to vulgarise my ideal loveliness and magnetic personality in order to gratify the curiosity of a number of persons who have never seen me, and never will. Let me never hear of such a proposal again. As the little boy said, “Myself is my own”; and, if it please you, part of

‘...the gleam,

The light that never was on sea or land,

The consecration, and the Poet’s dream.‘

‘Your wish is my law,’ I hastened to say, and was about to snatch at the first subject I could think of to ward off further reproof, when she held out a little posy of Penzance sweet-briar roses she had been wearing, saying in her sweetest manner, as though afraid she might have wounded me, ‘Are they not lovely? No, keep them, if you care to do so. They remind me of something I saw the other day, when, on my way to London for a few hours, the train halted between Waterloo Station and Charing Cross at a point overlooking a number of back plots and alleys of the humblest description; and the one immediately below me arrested my gaze. There were two short rows of the purest white linen, lately out of the wash-tub, hanging out to dry; and under them, a hammock, with a chubby baby in it, fast asleep. A few feet behind was a red-brick wall, and along its foot three rows of pelargoniums in full flower, and evidently most carefully hoed and watered. A comely looking woman, with her sleeves tucked up as far as they would go, came out of the house, peeped into the hammock, kissed, or rather hugged the baby, and then turned it round to screen it a little from the direct rays of the sun that were shining on this little paradise. Then the train moved on; and I thought to myself, with a feeling of quiet joy, that neither the garden that we love, nor the Tuscan garden that was our winter-quarters, nor all the gardens and palaces in the world, contain more happiness than those few yards of ground in one of the humblest parts of London, tenanted by linen hung out to dry, three rows of pelargoniums, a hammock with a sleeping child in it, and a loving mother.’

‘I wish I had seen it,’ I said.

‘I described it to the Poet,’ Lamia replied; ‘and he then did indulge in an Impromptu, which—let me think a moment—yes—ran somewhat like this:

‘How blest are they who hunger not

For riches or renown,

And keep, within a narrow plot,

A country heart in town;

‘Who envy not, though lowly born,

Luxurious lives above,

But blend with toil, renewed each morn,

The bliss of blameless Love.’