Читать книгу Voyage into Savage Europe - Avigdor Hameiri - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеTranslator’s Introduction

This book follows Avigdor Hameiri’s three books on the First World War and its aftermath—Hashiga’on Hagadol (The Great Madness), Bagehinom Shel mata (Hell on Earth) and Ben Shinei Ha’adam (Of Human Carnage)—and documents the only postwar trip that he took to Europe, during 1930. Its last chapter states that he made several “slight but important changes” during the years that followed. Because the book was ultimately published in 1938, not all the events described could have been experienced personally because of differences in dates.1 Where necessary, this is pointed out in the text. However, most of his experiences are current and powerfully evocative of a Europe teetering on the edge of a yet unknown catastrophe. Parts of this book were published in thirty-three articles in Doar Hayom between 9 October 1930 and 20 May 1932.

Hameiri arrives by boat via Brindisi in Trieste and then travels to points further afield. As with all his other books, his perception of his fellow travelers is often acerbic: he couldn’t have been an easy traveling companion. He has a good impression of the order and cleanliness of Mussolini’s Italy: Trieste is incomparably cleaner than it was under Austria-Hungary: the streets are clean, children begging for money are absent, and post office personnel are ordered and courteous.

Courtesy and consideration permeate every aspect of Viennese life; one is left wondering how this could have changed so radically overnight after the Anschluss. The Jewish population of Vienna are described as directionless. Hilda, the spoiled young girl with peasant clothes, a rich background, and confused ideas about Zionism is a case in point. The noxious racial ideas of Nazism have already begun to seep in, but Jews do not understand that extreme nationalism, as espoused by Adolf Hitler, is much more dangerous for them than Communism. In Hungary, Hameiri finds the large Jewish community sharply divided. At one end are Orthodox Jews, on the other are Jews who, assimilated and some even converted, try in vain to escape from their own Jewishness and inherent Hungarian antisemitism, thereby experiencing varying degrees of alienation. The community is split along Zionist and non-Zionist lines. In Hungary as well, the unseen enemy is approaching. The country is traumatized due to loss of two-thirds of its territory following the Treaty of Trianon in 1920.

During his visit to Romania, Hameiri visits Cluj Napoca (Klausenberg), capital of Transylvania, and several other towns in the region. Transylvania and the Banat had been annexed by Romania after the war, leaving Hungary severely truncated. His citation of poetry by Endre Ady—a turn of the century poet known and beloved inside, but almost entirely unknown outside, Hungary—is very moving. In 1905, strangely and presciently, Ady predicted the ruinous loss of Hungarian Transylvania. Here and elsewhere in the novel, Ady’s lines toll like a mourning bell predicting terrible events. Like many Hungarians (especially after the war), Hameiri has a low opinion of Romanians. Bribery and corruption prevail at railway stations and everywhere else during visits to towns such as Sighet (the birthplace of Eli Wiesel); Hameiri observes antisemitism, which did not exist when Transylvania belonged to Hungary. Romanians have acquired the rich farmlands of Transylvania, but the harvest lies rotting in the fields because Romanians have no idea how to apportion the land and harvest the crops.

The description of his visit to the village of his birth (now in the Eastern Slovak portion of the newly formed Czechoslovak state) is very moving. He stands outside his old house and it is as if an Old Testament prophet in the form of his beloved grandfather’s spirit is standing on the hill opposite, telling him: “Do not enter! Leave this place and go back where you came from!” Even the old pear tree whose fruit he had so enjoyed as a boy is old and holds no more attraction for him. He feels a premonition of coming terrible events in which the Jews will suffer. The Messianic vision of the 100-year-old Transylvanian village woman—“Leave at once: emigrate to the Land of Israel!”—is almost unbearably prophetic.

Hameiri’s description of Hungarian chauvinism may be at times exaggerated and irritating, but it reflects his love for Magyar culture. As befits an educated writer, poet, and former boulevardier, he is a bit of a snob, needlessly looking down on the poor people of Carpatho-Ruthenia. Both he and his interlocutors are incorrect when they boast of Hungary’s special martial prowess. There is no evidence that Hungarian soldiers were more willing to die in battle than others in the region. That said, he shows a deep understanding of Budapest culture, which was often inspired by Jews.

Hameiri comments scathingly about Rabbi Elazar Spira, leader of one of the Hasidic schools in Carpatho-Ruthenia. He compares him with other rabbis, and in the process gives us a picture of a vanished world destroyed during the Holocaust. His description of the ostentatious nature of Rabbi Spira’s daughter’s wedding in Munkács seemed ridiculous until I discovered a movie that had been made of the event. Difficult as it may be to believe today, borders were opened to let people stream to the event and police were necessary to keep back the crowds. Needless to say, Hameiri’s disdain for the hypocrisy of such a showy event knows no bounds. He has no patience for ultra-Orthodox rabbis who anathemize Zionists and Zionism and insist that Israel can only be redeemed by the Messiah and not by human efforts. He grasps the potential propagandistic power of motion pictures over the masses, and doesn’t think much of modern inventions such as jazz and cocktails. Although he has little time for American black artists like Josephine Baker, he excoriates American lynchings.

In all this chaos, Hameiri does find a few worthy people: the Czech statesman Tomáš Masaryk (who mercifully died before Hitler occupied Czechoslovakia) embodies everything good in a modern statesman. He holds up Albert Einstein and Bronisław Huberman as the consciences of a Europe gone wild and hurtling towards catastrophe—Einstein because of his steadfast pacifism and God-given ability to reduce the divine order of the universe into seemingly simple physics equations; Huberman because of his good deeds. It must be emphasized that Hameiri’s trip took place in 1930, but that the book was published in 1938, so interim events (such as the Spira wedding in 1933 and Huberman’s almost superhuman efforts in the mid-1930s to save Jewish musicians from the Nazis by helping them to emigrate to Palestine and found the Palestine Philharmonic Orchestra) also helped shape this work. The book must have been written over a period of time and revised several times, but we have no accurate information on this.

The last chapter (written four or five years after his trip)—presented here as a prologue—is especially compelling: “One more war and Europe will resemble a slaughterhouse.” Tragically, his prediction was all too true. In the final lines of the novel, he describes his book as joining many others on the bonfires of the auto-da-fé—a tragic, if unconscious, prophecy of Nazi book burning. Hameiri’s comments on the necessity of a European economic union to prevent war and promote conciliation are decades ahead of their time.

The timing of Voyage into Savage Europe prevented it from being read widely. It may have had a greater impact in the early 1930s, but, appearing as it did in 1938, the year of the Anschluss, the Sudetenland crisis and Kristallnacht, the Jews of Europe had other more pressing things to do than read a Hebrew book that was (ostensibly) about a trip in 1930, before Hitler had come to power. With the ability of hindsight, however, this is a great novel of warning. Hameiri is saying to the Jews of Europe, as God said to Abraham: Lech lecha.2 Emigrate to Palestine. Leave Europe by whatever means, catastrophe awaits you here!

Unlike The Great Madness and Hell on Earth, Voyage into Savage Europe has relatively little dialogue, making it more difficult to read. As if on purpose, it’s full of small factual errors about people (hair color, marital status, etc.). There is very little unabashed comedy, but a great deal of implied tragedy. The section about the living scarecrow who chases birds away for a living is symbolic of a disordered Europe that has lost its way.

The number of endnotes that I felt needed inclusion is very high because few readers will be cognizant of all the citations, people, and places mentioned in this book. This is particularly the case with Hungarians: I learned more about Hungarian history and culture while translating this book than I ever thought possible, given the impossible nature of the language. I was struck by the poetry of Endre Ady, whose weighty words, written in 1905, sound like those of an Old Testament Jeremiah. It seems to me that his poetry is the axle around which the book turns, and I thank Miriam Neiger with help translating his emotionally profound work. The reader is reminded of the huge Hungarian Jewish contribution to the arts and sciences during the period before the Second World War. The many instances of Hebrew puns and wordplay, as well as Biblical and Talmud quotes, also required clarification in the endnotes. This book is essential reading for anyone who wishes a deeper understanding of the Jewish situation in Central Europe during the fateful 1930s.

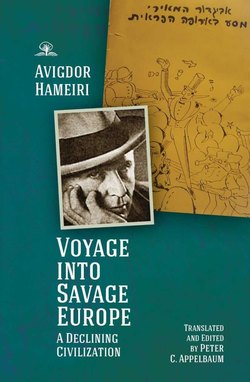

I thank my Hebrew teacher Siegbert Silbermann z’l for his wise counsel and guidance that has shaped my lifelong love of the Hebrew language. I thank Dan Hecht for his excellent introduction, János Köbányai for help with Hungarian names, the Shapira brothers for their approval to translate another of their grandfather’s novels, also for the photograph and original book cover, and Avner Holtzman and Glenda Abramson for patient translation and other advice. Hillel Halkin provided invaluable and patient guidance when I had the chutzpah to embark on translating Hebrew novels. István Deák provided insightful comments on the text and endnotes. Benton Arnovitz kept faith with me, providing invaluable encouragement and advice in finding a publisher. Esther Dell (Hershey Medical Center Library) provided me with a copy of Hameiri’s original manuscript, stained with age, from which to work; and Heather Ross (Donald W. Hamer Center for Maps and Geospatial Information, Penn State University Libraries) did yeoman service providing the map. Alessandra Anzani, Stuart Allen, Jenna Colozza, Matthew Charlton, and Kira Nemirovsky at Academic Studies Press were a pleasure to work with at every stage of the publication process. As always, my wife and partner in all things, Addie, cast a critical eye on the manuscript. Both she and my daughter Madeleine helped provide the loving background which enables me to work, mumbling uninterruptedly in several languages at once. Any translation or annotation errors are mine alone.

Peter C. Appelbaum

Land O’Lakes, Florida, March 2020