Читать книгу The Dispossessed - Aviva Chomsky - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

By Lance Selfa

To be dispossessed is to be evicted, ousted, or uprooted. The word used in Colombia to describe a similar state of being is desterrado. The verb desterrar, from which it is derived, means “to cast someone from territory or land by a judicial order or governmental decision.”1 It describes the more than three million Colombians dispossessed since 1985 living in ramshackle refugee camps, rural refugees living in urban slums, and others who have been forced to flee the country for their lives. For these people, leaving their land or the towns of their birth means more than “displacement” to some other part of the country. It often means losing their livelihoods, their family ties, and any sense of stability in their lives. And, while very few have actually received legally enforceable orders of expulsion, most know that the hand of the government and landowners—usually operating through shadowy networks of paramilitaries—lies behind the forces that put them to flight.

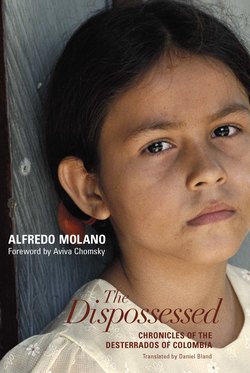

Haymarket Books welcomes the opportunity to bring The Dispossessed, published under the title Desterrados in Colombia in 2001, to an English-speaking audience for the first time. We are also honored that Alfredo Molano, one of the most respected journalists and scholars in Latin America, allowed us to publish Daniel Bland’s fine translation of this work. We hope that it will increase Molano’s audience in North America and that it will serve to educate the public about a country that did not receive its first comprehensive historical treatment in English until 1993.2

Molano’s Desterrados is part of a cultural phenomenon of literature focused on themes of violence and displacement in Colombian life. This literature includes Laura Restrepo’s La multitud errante (The Wandering Multitude), Marisol Gómez Giraldo’s 2001 work also titled Desterrados, and Fernando Vallejo’s La virgen de los sicarios (Our Lady of the Assassins), a 1994 novel that director Barbet Schroeder adapted into an award-winning 2000 film. María Helena Rueda explained the popularity of the literature of displacement in Colombia in the early 2000s:

Displacement is a palpable and tragic reality. But it is also a metaphor for life today in Colombia. Colombia is a country that, for the people who live there, has been transformed into a foreign land. It is unrecognizable, not only because of violence, but because of other processes that have been strengthened in recent years. The state has weakened; there is an absence of ideological discourse to link people to a struggle for democracy; unemployment looms like a ghost; socioeconomic imbalances resulting from drug trafficking and corruption are profoundly unsettling; the bankruptcy of industries that could not survive free market reforms which liberated imports and the crashing of coffee prices—all of these phantoms are the life companions with whom the Colombian people have had to learn to co-exist in recent years.3

By early 2002, Molano’s Desterrados had reached seventh in book sales in Colombia. Reviewers praised its honesty and willingness to reveal truths that polite society would rather have ignored. “These chronicles shake you to the core,” wrote Luis Barros Pavajeau in the online cultural review La Esquina Regional. “However, they are part of the other country, one that feels far from the large cities. A country that covers itself with a cloak of silence, to dodge the shame of a reality that still fills every corner.”4 Antonio Caballero, a columnist for the weekly Semana, cited the story of Toñito, related in “The Turkish Boat,” in a broadside against the government’s failure to protect the country’s children from violence.5

When Desterrados appeared in Colombia, its author was marking his second year in exile from the country. As he describes in his personal memoir, “From Exile,” Molano fled Colombia for Spain on Chistmas Day, 1998. He had become a target of the country’s paramilitaries after serving as an adviser to the president’s appointed commission charged with investigating the possibility of entering into peace negotiations with the guerrilla oppositions, the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and the National Liberation Army (ELN). Through this work, Molano became increasingly outspoken about the obvious (but unacknowledged) collaboration between the Colombian armed forces and the right-wing paramilitaries, who carried out horrific massacres of peasants in the name of fighting the guerrillas. Spokes men for the “paras” (as the paramilitaries are known) openly threatened Molano with death. Molano discovered that two suspicious men loitering outside his house were soldiers dressed in civilian clothes, and an armed forces commander assigned to protect him admitted that the army couldn’t protect him from would-be assassins. The last straw came when paramilitaries, citing “irrefutable proof” that Molano was a “paraguerrilla,” delivered a threat to the editorial offices of El Espectador, the liberal Bogotá newspaper where Molano writes his weekly column. After nearly five years in exile in Spain and the United States, Molano returned to Colombia in early 2004.

Molano makes no secret of his identification with the political Left, but the charge that he is a “paraguerrilla” is absurd. As he told an American interviewer in 2000, he faced death threats because

I am a man of the Left and of the university, more or less. I continue being very critical in Colombian society of the political system, including of the army and naturally the paramilitaries. This doesn’t mean I’m totally in agreement with the guerrilla, although I agree with them on many things. I agree with agrarian reform. I agree with the reforms they’ve proposed for the army. I agree with the reforms of the media and the justice system. But naturally I don’t agree with everything. First, because the guerrilla has Stalinist roots. They are military forces and this gives a lot of force to authoritarian tendencies. I place myself at a distance from that. But my critiques of the system, of the great landowners, of the ranchers, of the army, of the paramilitaries, these are what caused the threats. And the threats grew until I saw that not only was I in danger but my family and those close to me.6

Molano is one of Colombia’s leading public intellectuals, the winner of major awards for his scholarly and journalistic work. A trained sociologist with an advanced degree from the École Pratiques des Hautes Études in Paris, he served in executive positions in several nongovernmental organizations addressing issues of environmental and rural development before taking a position with the government’s peace commission. Although well recognized for his academic publications, Molano turned to a new arena—newspaper and television journalism—in the late 1980s. Since 1991, he has written a weekly column in El Espectador. In 1993, he won the Simón Bolívar Journalism Prize for an episode of the television documentary “Travesías” about Colombia’s indigenous in the town of Chenche. Journalism gave him a wider audience than those who had read his technical reports. It carried a cost, as well:

I think people began reading me with a mixture of surprise and disbelief. Gradually, though, they began to feel something and like—or dislike—the people I described in my chronicles and stories and in my weekly column. But that created a problem because as more readers became interested and began to defend my notions of the country, more enemies appeared. (p. 43)

Molano found increased interest in his work because many of his readers could empathize with the human stories he told. As Aviva Chomsky’s foreword points out, Molano’s trademark style is firmly rooted in the Latin American tradition of testimonial literature. This method imbues Molano’s work with an authenticity and a radicalism—not in the sense of a political tract, but that of “going to the root of the problem.” Molano’s work holds a mirror up to Colombian society, trying to present it as it is. He captures the point of view of ordinary people—from peasant activists to drug couriers. His method brings to mind Russian revolutionary V.I. Lenin’s admonition that “one must always try to be as radical as reality itself.”7

The view of Colombia that emerges from Molano’s crónica is that of a country where deadly violence accompanies everyday life like the rain or sun. In “Ángela,” the young narrator dwells mostly on memories of her childhood. Violence only intervenes, initially, as a disruption of her play: “We used to go down to the river a lot to cool off, especially in the afternoon, until my father forbid it because of the bodies that began to float by. He didn’t want us to see them” (p. 69). In “The Garden,” another narrator remembers, thirty-seven years after the event and rather matter-of-factly, the day assassins broke into her first communion celebration. Their victim’s blood splattered across her white dress. The violence erupts and engulfs the individuals, who often admit they have no idea how they could have become ensnared. Ángela’s father realizes he has to flee after paramilitaries accuse him of ferrying guerrillas across a river. “But my father didn’t know who they were,” says Ángela (p. 70). The four protagonists of “Silences” seem more interested in living out their retirement years in Boca del Cajambre than in the conflicts around them. Yet paramilitaries murder old Ánibal after he makes the mistake of sharing Christmas Eve dinner, drinks, and a shower with members of a guerrilla unit.

For the most part, the people who tell Molano their stories are apolitical, in the sense that most of them are not political activists or guerrillas. But this should not blind us to the fact that the violence and the displacement have very clear political and economic roots.8 Documenting these political, social, and economic roots of the desterrados is the contribution of Mabel González Bustelo’s essay “Desterrados: Forced Displacement in Colombia.” González Bustelo, a Spanish journalist and researcher with the Centro de la Investigación para la Paz (Peace Research Center) in Madrid, helps us to grasp both the magnitude and the causes of the problem of forced displacement in Colombia, clearly linked to a neoliberal economic model that focuses on Colombia’s export industries:

Forced displacement is a phenomenon linked to the history of Colombia and to the country’s unfinished historical processes. The economic and political elite have used displacement to “homogenize” the population in a given area and to maintain and expand large estates. Currently, the pressure exerted by the neo liberal model to increase capital circuits has made the process more difficult by introducing factors that change the value of the land. As such, people are not displaced “by violence”; rather, violence is the tool used to expel the population. The true causes for displacement are hidden behind the violence. The reasons for displacement include strategic control of military and political areas, restructuring of local and regional powers, control or disruption of social movements, control of production and extraction activities (of natural resources and minerals), mega-projects, expansion of stockbreeding estates and agricultural industry, control of illicit crops, etc.9

The current war between the Colombian state, the paramilitaries, and the guerrillas must be viewed in this context. González Bustelo has written that Von Clausewitz’s famous aphorism can be adapted to Colombia today as “war is the continuation of economics through other means.” This phrase not only describes the historic employment of private landlord armies to seize prime farmland, but also today’s neoliberal policies that slash state education and health services to such a point that huge areas of the country seem untouched by any state presence except the military. In this “Wild West” atmosphere, paramilitaries and guerrillas can fill the void so that entire regions of the country become immune to Bogotá’s influence. Neoliberal policies forcing competition between small Colombian farmers and international agribusiness drove more than five million farmers off their lands in the 1990s. In many cases, farmers turned to the production of coca and other illicit crops as a means to survive. In other cases, landlords hired paramilitaries to drive farmers out and replaced production of food crops with livestock. This is why Molano once described Colombia as “a country where a cow is worth more than a person.”10

Another aspect of globalization and neoliberalism is the role of international capital in the chain of events that forces thousands off their lands. Colombia is one of the richest natural-resource-producing countries in the world. Multi nationals investing in minerals, cash crops, petroleum, and other products contribute to the pressure to expel populations that get in the way of their unfettered access to the country’s resources. As González Bustelo shows, British Petroleum financed paramilitaries. In the late 1990s, Occidental Petroleum lobbied Congress to expand the area covered under Plan Colombia to places where the company had its investments. One study estimated that 84 percent of the displaced come from areas that produce 78 percent of the country’s oil revenues.11

If violence is part of doing business in Colombia, both international and Colombian firms feel no qualms about employing it to repress activities, such as labor and peasant organizing, that might impede their search for profits. Human Rights Watch and the AFL-CIO confirm that Colombia is the most dangerous place in the world for trade unionists to organize. Since 1991, more than three thousand trade unionists died at the hands of assassins.12 Likewise, “Forced migrations take place in areas where people are not politically active (as shown in their electoral participation) but very socially active (protests, demonstrations), proving the high social costs of the displacements,” González Bustelo shows.13 Especially targeted are areas with traditions of farmworker, peasant, and indigenous rights organizing.

The testimonies presented in The Dispossessed describe in the most personal terms how these larger economic and social processes play out in ordinary people’s lives. Paramilitaries enter the scene of “The Defeat” as a protection force for “Don Enrique Ortiz, a businessman who bought all the wood he could get his hands on to sell to Cartones Colombianos” (p.56), a major cardboard manufacturing multinational. Harvesting the wood in question was illegal, and “finding (out) about that little business … proved to be the beginning of the end for Diego and his friend Aníbal,” the protagonists of the story (p. 56). The drug economy—and the paramilitaries’ fight to control it—figures prominently in a number of the crónicas. The narrator in “Silences” recounts his participation in a strike on a banana plantation. The plantation bosses call in the local military commander who warns the banana workers that they might be taken for guerrilla sympathizers. The following day, the narrator finds the bodies of two union leaders hanging from a banana tree. The strike was crushed, and the narrator flees the plantation, remarking, “No one was ever punished for those murders, and the bosses never lost as much as a minute’s sleep over them” (p. 87). Yet, for this narrator, paramilitary violence didn’t intimidate him forever. “Silences” stands out as an account of someone who not only learns to cope with the violence, but to stand up to it. He becomes a campesino organizer who finishes his narrative on a note of hope and defiance: “As for me, I’m still with my people. We’ve stopped running and decided to resist. Without weapons or a thirst for vengeance but with the land we’ve worked and made something of together. The land that is us all” (p. 96).

The stories also document guerrilla relations with the rural population. They paint a picture that neither echoes the Colombian (and U.S.) government’s fulminations against “narcoterrorists,” nor excuses the guerrillas for their sometimes brutal treatment of their presumed constituents. It is notable that the narrator of “Silences,” who clearly identifies himself as a church-based activist, describes this dynamic in the field of peasant organizing: “When the church in its way, and the guerrillas in their way, threw in with the people, the paramilitaries and the army appeared” (p. 95). In other words, the narrator saw himself and the guerrillas to be fighting on the same side, the side of the campesinos. To the narrator of “Nubia, La Catira,” the guerrillas were defenders of campesinos, meting out frontier justice against bandits who preyed on coffee farmers. Nubia says, “The guerrillas were good people, not rude or bad-mannered…. The guerrillas taught me to read and write and I always wanted them to take me to their camp” (p. 179). On the other hand, we also see the guerrillas as inflexible and domineering. Ninfa, the narrator of “The Garden,” loses both her father and husband to guerrilla executions. In both cases, the guerrillas are deceived into thinking the condemned to be collaborators with the paras, but this is no consolation to Ninfa: “I’ll never forgive the guerrillas for not trying to find out more about what happened, about our mistake. We acted in good faith. The paracos tricked us, and, what’s more, they tricked the guerrillas as well into committing a crime” (p. 135).

Despite this, Molano’s informants leave no doubt that they believe the paramilitaries and their collaborators in the police and military to be the chief source of violence in the countryside. Statistics back up Molano’s informants. Right-wing paramilitaries account for two to three times the number of forced displacements than the guerrillas have caused, according to the United Nations. One 2001 report estimated that paramilitaries account for 79 percent of all human rights violations against civilian populations, compared to 16 percent of human rights violations attributed to guerrillas.14 These paramilitary actions contributed to conditions that caused the majority of 412,000 to flee their homes in 2002, and an additional 175,000 to flee in 2003, according to the nongovernmental Consultancy on Human Rights and Dis placement (CODHES). Given the prevalence of forced displacement in the countryside, it is understandable why each story revolves around a horrific act of paramilitary violence. “Whenever there were bodies in the river,” the child Ángela says matter-of-factly, “the paramilitaries showed up” (p. 73).

The clear collaboration between the official military, the police, and the paramilitaries is well-documented. In fact, some observers have likened the increase in para military activity to a “privatization” of the state’s repressive apparatus, providing the government with “plausible deniability” while it seeks to wipe out guerrilla and other challenges to its rule.15 A January 2004 Human Rights Watch report states the case unequivocally:

Although the Colombian government describes these ties as the acts of individuals and not a matter of policy or even tolerance, the range of abuses clearly depends on the approval, collusion, and tolerance of high-ranking officers. The Uribe Administration has yet to arrest paramilitary leaders or high-ranking members of the Armed Forces credibly alleged to collaborate with abusive paramilitary groups. Arrest statistics provided by the military are overwhelmingly skewed toward low-ranking members of paramilitary groups or individuals whose participation in these groups is alleged, not proven.16

By some estimates, the paramilitaries control as much as one half of the country’s illicit drug trade, producing revenue of $1–$2 billion annually. Therefore, the paras are not a ragtag band, but a virtual, and well-financed, state within a state.

Human rights activists charge that the Uribe government’s plans to accept surrenders of paramilitary leaders and the disbanding of their units are either a smokescreen for international consumption or a step toward the legalization of the paramilitaries and their open integration into the armed forces.17 The question posed by narrator Osiris, who loses a husband and son to the paras, remains unanswered: “Where do you demand justice when the authorities who pick up the bodies are the same ones who kill them? Who do you denounce the crime to if the authorities are all smeared with blood?” (p. 159).

When people are forced to flee, they end up in camps for displaced persons, other towns, or as country people living in the slums of major cities like Bogotá or Medellín. The Dispossessed captures their disorientation of living as strangers where they are often not welcome. Perhaps the most dramatic of these accounts is the story of the boy Toñito, told in “The Turkish Boat.” Fleeing a paramilitary massacre of his village in the Chocó region—a massacre that leaves him an orphan—he takes a riverboat all the way to the Caribbean port city of Cartagena. There, residing in the Mandela slum with thousands of other desterrados, he describes his life: “I lived with a gang in the street. We hustled anywhere we could” (p. 110). He and his gang run afoul of the local police and mafia, compelling him to stow away on a Turkish vessel bound for New York. Toñito barely survives that escape attempt, as the ship’s captain orders the stowaway thrown overboard.

The desterrados’ move from the countryside to the city introduces them to a different set of challenges than those they faced in their villages. There are the politicians and priests who demand payoffs for their help in finding housing, food, and job assistance for the displaced. There is the danger of street crime—from petty theft to murderous drug turf battles. Consumer goods are more available in the city, but food is less plentiful and more expensive. And the displaced face racism and discrimination. Osiris, of Afro-Colombian descent, recounts an incident in which a man, firing shots at her family’s home in the middle of the night, taunts them: “Come out of there, you displaced sons-of-bitches, fucking guerrillas! Come out and die!” Osiris puts on a brave face: “It turned out to be one of the neighbors who’d had too much to drink and decided to make fun of us for being displaced. It was a joke. But jokes have their poison and drunks say what they really feel. Things here are difficult” (p. 170).

The question of violence and displacement

“The roots of Colombia’s crisis lie in its historically weak state, a divided ruling class, and a closed two-party political system that has blocked any participation or voice from the mass of the population,”18 write Tristin Adie and Paul D’Amato, summarizing the main reasons for the violent nature of Colombian society. For the first century and a half of Colombia’s existence as an independent state, the elite-based Liberal and Conservative Parties, whose influence reached from Bogotá to every rural town, rotated in and out of government with a regularity lampooned in Gabriel Garcia Márquez’s One Hundred Years of Solitude. Periodic party competition led to armed conflict, with militias of Liberals and Conservatives squaring off in rural areas. Throughout most of this time, the mass of the population remained excluded from the political spoils, or, in the case of some peasants, remained tied to the Liberals or Conservatives.

This began to change in the 1930s, when, during the Great Depression, labor and peasant organizing put pressure on the political system. The Liberal governments of the 1930s enacted measures providing for social security and workers’ rights akin to U.S. president Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal or the state-led reforms of Mexican president Lázaro Cárdenas. As in the United States, this period of reform was short-lived. The Second World War and the subsequent Cold War put a damper on popular aspirations, giving the Colombian Right an opening to roll back the 1930s reforms. President Alfonso López Pumarejo, who had played the FDR role in the 1930s, returned to power in the war years only to lead a retrenchment in the reforms he had championed. This ignited a populist movement inside (and outside) the Liberal Party, in which the Left, workers, and peasant organizations rallied behind the charismatic politician Jorge Eliécer Gaitán. Gaitán came in third in the presidential elections of 1946, not far behind the official Liberal candidate. He looked to be in a strong position to win the 1950 election. However, on April 9, 1948, an assassin cut down Gaitán on a Bogotá street. The assassination ignited the Bogotazo, weeks of mass rioting in the capital and beyond, as Gaitán supporters accused the Conservatives or official Liberals of murdering their leader. After a brief respite, the violence reignited, this time engulfing the country in a cycle, which has since been called La Violencia, lasting through 1958. Eduardo Galeano describes La Violencia:

The violence began with a confrontation between Liberal and Conservative Parties, but the dynamic of class hostilities steadily sharpened its class struggle character.… When [Gaitán] was shot dead, the hurri cane was unleashed. First the spontaneous Bogotazo—an uncontrollable human tide in the streets of the capital; then the violence spread to the countryside, where bands organized by the Conservatives had for some time been sowing terror. The bitter taste of hatred, long in the peasants’ mouths, provoked an explosion; the government sent police and soldiers to cut off testicles, slash pregnant women’s bellies, and throw babies into the air to catch on bayonet points.… Liberal Party sages shut themselves in their homes, never abandoning their good manners and the gentlemanly tone of their manifestoes.… It was a war of incredible cruelty and it became worse as it went on, feeding the lust for vengeance.19

La Violencia took the lives of as many as 300,000 Colombians. It came to an end only when the Liberals and Conservatives agreed to a National Front pact in 1958. In the pact, the two parties agreed to trade the presidency every four years and to divide up the spoils of government between them. This arrangement held until 1974. As Jenny Pearce has explained,

The state was … literally carved up by the traditional parties. In addition to alternating the presidency between them for 16 years, all legislative bodies and public corporations … cabinet offices, judicial posts and posts at all levels of public administration were to be distributed by agreement between the two parties.

No expression of social conflict was permitted outside the control of the two traditional parties.20

While the National Front governments quelled the interparty conflicts, they did not end the peasant insurgencies sparked during La Violencia. In the 1950s, Conservative governments—with backing from the United States—launched major military operations against peasants who wanted to protect and extend the land reforms of the 1930s. These military operations stimulated the organization of peasant self-defense forces into guerrilla armies in which Colombia’s small Communist Party played a role. Focused on the nearly uninhabited departments (a subnational unit of government similar to a state government in the United States) of Meta and Caquetá, these peasant armies set up “independent republics” intended to allow peasants to work the land free of interference from the central government. But the central government and great landlords had no intention of ceding their authority to the independent republics. Instead they defined the peasant leaders as “communists and bandits” and set about re conquering the land from them. As Molano wrote in an important 1992 study of this process, “The only possible out come was war. One by one the republics fell to the army, and once they were under government control the land became concentrated in the hands of the large landowners.”21

Government and landlord assaults provoked a counter-mobilization among the peasants and others who found themselves locked out of the country’s closed political system. “Seeing that it would be impossible to break through the rigid political and agrarian structures using legal means, the opposition declared an armed rebellion. During the same period other guerrilla forces, the National Liberation Army (ELN) in 1964 and the People’s Liberation Army (EPL) in 1967, were created, and the big landowners dominated the country’s economy.”22 In 1966, several guerrilla forces tied to the Communist Party fused into the FARC. Through many political, ideological, and military twists and turns, the FARC and the ELN have established themselves today as the most durable guerrilla forces in Colombia. However, they have not been the only guerrilla challengers to the Colombian government. In the 1970s and 1980s, the urban-based guerrillas, the M-19, rose in prominence. But the M-19’s seizure of the Palace of Justice in 1985—which resulted in the immolation of the Supreme Court and the deaths of many judges, lawyers, and ordinary citizens—provoked a backlash against it. Even though the Colombian military leveled the Palace of Justice in its assault on M-19 guerrillas, the government seized the initiative to deliver a crushing blow to the M-19. A 1989 government amnesty to M-19 members brought former guerrillas into the electoral arena and propelled one M-19 leader, Antonio Navarro Wolf, into a position with the Colombian government in the 1990s.

However, Wolf’s transition from guerrilla to mainstream politician was the exception. The majority of M-19 members, as well as thousands of guerrillas from the FARC and other formations, took seriously the government’s 1984 invitation to lay down their arms and to compete in the electoral arena. They formed Unión Patriótica (UP), a left-of-center electoral front, in 1985 to compete in the 1986 presidential and newly approved local government elections.23 Looking forward to the 1986 elections, FARC leader Manuel Marulanda, known by his nom de guerre Tirofijo (“Sureshot”), spoke of his desire to return to political life as a local town counselor. But the government and the armed Right reneged on their promises. The false dawn of the 1986 elections “proved to be a great deception; the UP was literally annihilated as many of its leaders and hundreds of its candidates for office were murdered.”24 In fact, human rights workers have documented more than 3,000 murders of UP activists. With the UP experiment a shambles, the guerrillas returned to the hills and took up arms again.

It goes without saying that this history forms the backdrop to the stories of the desterrados told here. In some cases, the historical connections are more direct. The narrator of “The Garden” relates that her father was a guerrilla during La Violencia. “They turned over their weapons to the army during the [1953–57] Rojas govern ment—getting nothing in return that time—and that’s when he met my mother” (p. 119). The narrator of “Silences,” describes his father as a guerrilla who joined a Liberal unit founded “to avenge the murder of … Jorge Eliécer Gaitán” (p. 82). The mother of Nubia, La Catira, was president of the Unión Patriótica party in her town, chosen, no doubt, in recognition of her work in pressuring the government to deliver roads, health care, and schools. Sadly, her mother was one of the thousands of UP activists who died at the hands of military-controlled death squads that wanted to close Colombia’s “opening to democracy.”

As the guerrilla war began again, two new elements jumped into the vortex of violence: the drug cartels and the paramilitaries. In fact, the two rose side by side, as the major drug cartels in Medillín and Cali financed and armed many of the original paramilitary forces. Colombian peasant farmers, facing ruin and poverty in the 1970s and 1980s, turned to coca production as a lucrative and easily transportable crop. Guerrillas levied “war taxes” on middlemen who facilitated transport of the coca from the fields to the cartels, allowing them to finance a range of social services for the rural poor. But the cartel leaders invested part of their superprofits in land and cattle—placing them in league with the traditional enemies of the rural poor and guerrillas. And when guerrillas turned to kidnapping and ransoming of wealthy “narco-landowners,” the druglords created “death to kidnappers” paramilitary groups to fight the guerrillas. The drug cartels’ creation of death squads overlapped with the traditional oligarchy’s opposition to any negotiated settlement with the guerrillas. Forces inside the military opposed to the guerrillas also took advantage of a loophole in Colombian law allowing them to create “self-defense forces,” or autodefensas, private militias armed by the military. The result of all this was a huge increase from the 1980s to today in paramilitary activity, including massacres, disappearances, and forced displacements.25

Since the drug cartels, the traditional oligarchy, and the military represented an alliance of sectors of Colombia’s ruling class, it wasn’t long before paramilitary activity became directed not just at guerrillas, but at any force inside Colombian society that dared to challenge the status quo. Human rights workers, trade unionists, peasant leaders, left-of-center politicians, and others having little or nothing to do with guerrilla activity became targets of the paramilitaries. In the cities—especially in the slum areas where many of the displaced concentrate when they flee to urban areas—“social cleansing” by hired assassins (sicarios) annually murders hundreds of street children, prostitutes, and others deemed “undesirable.”26 An account of just such an incident of “social cleansing” forms the core of the story in “The Turkish Boat.”

Given the horrific conditions and the climate of repression that so many Colombians experience, the continued resilience of labor and peasant movements and the desire of ordinary Colombians to forge a better future is remarkable. Despite the conditions of civil war and the government’s penchant to label all opposition as “terrorism,” more than two million Colombians engaged in strikes to protest austerity measures in 1999. In 2003, Colombian voters defeated a referendum with which President Alvaro Uribe attempted to ram through huge spending cuts and to win approval for near-dictatorial powers. At the same time, voters chose members of the Independent Left Pole, a coalition of trade union, human rights, and social movement activists, to run many of the country’s major cities and departments, including Bogotá.

The United States and the violence in Colombia today

What happens in the Colombian cordillera may seem distant from the everyday lives of North Americans. But connections between Colombia and North America—and the United States in particular—are not hard to establish. The United States has actively intervened in Colombian affairs throughout the country’s modern history. As a leading producer of raw materials, including oil, and with its geographic position at the crossroads of Central America and Latin America, Colombia has long figured in U.S. strategic planning. In the early 1900s, the United States helped to sponsor a secession movement in Colombia’s northwest that resulted in the creation of the country of Panama—just in time for the new nation to cooperate with U.S. plans to build a canal there. In the period of the Cold War, Colombia became a major recipient of U.S. foreign aid and the major testing ground for the Alliance for Progress.27 Economic and development assistance combined aid to Colombia’s armed forces. The administration of President John F. Kennedy advised the Colombian military to “select civilian and military personnel … as necessary [to] execute paramilitary, sabotage and/or terrorist activities against known Communist proponents. It should be backed by the United States.”28 To fulfill that goal, the United States trained as many as ten thousand officers in the Colombian armed forces and security services at the infamous School of the Americas (recently renamed the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation).

In the 1990s, Colombia once again took center stage in U.S. policy toward Latin America, as the country became the cockpit for the U.S. “war on drugs.” As the Cold War ended, U.S. policy-makers cast around for new rationales for U.S. military intervention that had been justified as necessary to confront “communism.” In Latin America, “fighting drugs,” “narcoterrorists,” and “narcoguerrillas” filled the bill. As a former Reagan administration defense official explained, “Getting help from the military on drugs used to be like pulling teeth. Now everybody’s looking around to say, ‘Hey, how can we justify these forces?’ And the answer they’re coming up with is drugs.”29 Yet, as many observers of U.S.-Colombian policy have pointed out, the focus of the anti-drug war has overlapped closely with guerrilla-controlled areas—even though U.S. and Colombian officials agreed that the guerrillas were not the country’s main cocaine traffickers. In other words, the war on drugs is essentially a counterinsurgency program intended to defeat the guerrillas. In 2002, the Bush administration made this rationale official when it announced that its Colombia policy would be conducted under the rubric of fighting “terrorism.”

Today, Colombia is the third-largest recipient of U.S. military aid, behind Israel and Egypt. Between 2000 and 2003, the United States spent $2.4 billion in aid for Colombia, 80 percent of it directed to the military and police. In 2002, the U.S. authorized $99 million to pay for protection of the Caño Limón-Coveñas oil pipeline, with almost half of its capacity dedicated to U.S.-based Occidental Petroleum.30 In January 2004, the Bush administration released $34 million to the Colombian armed forces, certifying that Colombia had fulfilled State Department human rights requirements to break with paramilitary organizations. The government of Alvaro Uribe, elected in 2002 on a platform promising harsh repression of the guerrilla opposition, remains one of the chief allies of the Bush administration in Latin America. In these ways, the U.S. government stands out as the chief external backer of the armed forces—and, by extension, their paramilitary allies—in Colombia. These are precisely the forces overwhelmingly responsible for turning millions of their countrymen and women into desterrados.

Luis Adolfo Cardona is one such person whom I have met in Chicago. Luis Adolfo was an organizer in the National Food Workers’ Union, SINALTRAINAL, and a forklift operator at the Coca-Cola plant in Antioquia before he had to flee his country. His story is similar to those recorded in The Dispossessed. Narrowly escaping a kidnapping by paramilitaries in 1996, he fled to Bogotá. After receiving death threats there, he fled the country. The AFL-CIO Solidarity Center’s program to protect Colombian trade unionists offered him and his family refuge in the United States. In late 2003, he won political asylum in the United States. He works tirelessly, speaking to union members, students, and church groups about the repression of trade unionists and of the paramilitaries’ connections to Coca-Cola and other U.S. companies. While human rights reports can describe the repression in Colombia, no one can better convey what it really means than someone like Luis Adolfo or the people whom Alfredo Molano has recorded in this book. We publish The Dispossessed in North America in the belief that if Americans knew the full extent of the misery that their government supports in Colombia, they wouldn’t stand for it.

“Maybe it would be better for us if we didn’t talk about what happened, about our history,” says Osiris, the narrator of the chronicle named for her. “But if we don’t tell people about it, all of our dead will remain dead forever. We may have to bury them but that doesn’t mean we are ever going to forget them” (p. 174). In The Dispossessed, people like Osiris help us not only to remember the dead, but motivate us to do what we can to change the conditions that led to their killings.

1 According to the first definition offered in the Diccionario de la Lengua Española, 21st edition (Madrid: Real Academia Española, 2001).

2 David Bushnell, The Making of Modern Colombia: A Nation in Spite of Itself (Berkeley: University of California, 1993).

3 María Helena Rueda, “Chronicles of the Banished: Displacement and Popular Identity in Colombia,” GSC Quarterly, no. 4, Spring 2002, Social Science Resource Council, Washington, D.C.

4 For the sales ranking of the book, see http://www.losandes.com.ar/2002/0403/suplementos/cultura/nota68154_1.htm. Quotation is from a review of Desterrados by Luis Barros Pavajeau, La Esquina Regional, diciembre 2002–febrero 2003, at http://www.laesquinaregional.com.

5 Antonio Caballero, “Niños infelices,” Semana, July 19, 2001, at http://www.semana.com/archivo/articulosView.jsp?id=18946.

6 “Hidden Motives for a War,” NARCO News Bulletin, August 7, 2000, at http://www.narconews.com/exiled.html.

7 See Alexander Cockburn, “Radical as Reality,” Green Left Weekly (Australia) at http://www.greenleft.org.au/back/1991/37/37p13.htm. The quotation is attributed to the 1927 memoir of Valeriu Marcu, Lenin: 30 Years of Russia (Berlin: Paul List/Verlag, 1927).

8 “The term ‘displaced’ denounces the intention to mask one of the most tragic and bloodthirsty episodes of our time. The truth is that people do not move: they are moved, exiled, expelled, forced to flee and hide. Another method used to conceal this fact consists in seeing it as if it were the result of clashes between two new actors: the guerrillas and the paramilitary. Nevertheless, population expulsions are but an old resource used by the system, which, by pointing to illegal armed groups as the original source of the problem, exonerates the Regime and above all the Armed Forces from all responsibility.” See Alfredo Molano, “Desterrados,” en Papeles de cuestiones internacionales, no. 70, Spring 2000, Centro de Investigación para la Paz, Madrid.

9 Mabel González Bustelo, “Desterrados: Forced Displacement in Colombia,” in this volume, p. 232.

10 Cited in Nectalí Ariza Ariza, “El Conflicto Colombiano y la Coyuntura Internacional, at http://www.ccoo.illes.balears.net/asociaciones/pau/observatori/colombiaanalisis.pdf.

11 González Bustelo, p. 209.

12 See “International Union Body Makes Breakthrough with Colombian Authorities,” February 3, 2004, International Confederation of Free Trade Unions, at http://www.icftu.org.

13 González Bustelo, p. 210.

14 See a summary of the relevant data in Norwegian Refugee Council, “Profile of Internal Displacement: Colombia,” February 2004, 35ff.

15 Ricardo Vargas Meza, “The FARC, the War and the Crisis of the State,” NACLA Report on the Americas 31(5), March–April 1998, p. 23, and “The Wars Within: Counterinsurgency in Chiapas and Colombia,” op. cit., p. 6.

16 Quoted from “Colombia: Briefing to the 60th Session of the UN Commission on Human Rights, at http://hrw.org/english/docs/2004/01/29/colomb7124_txt.htm.

17 Juan Forero, “800 in Colombia Lay Down Arms, Kindling Peace Hopes,” New York Times, November 26, 2003.

18 Tristin Adie and Paul D’Amato, “Colombia: The Terrorist State,” International Socialist Review, no. 10 (Winter 2000), p. 21.

19 Eduardo Galeano, Open Veins of Latin America: Five Centuries of the Pillage of a Continent (New York: Monthly Review Press, 1973), pp. 116–17.

20 Jenny Pearce, quoted in Adie and D’Amato, p. 22.

21 Alfredo Molano, “Violence and Land Colonization,” Violence in Colombia: The Contemporary Crisis in Historical Perspective, Charles Bergquist, Ricardo Penaranda, and Gonzalo Sanchez, eds. (Wilmington: Scholarly Resources, 1992), p. 199.

22 Alfredo Molano, “The Evolution of the FARC: A Guerrilla Group’s Long History,” NACLA Report on the Americas 34(2), September–October 2000. While the FARC and ELN remain active today, the majority of EPL members surrendered their arms in the early 1990s to participate in “above-ground” political activity.

23 Before 1986, the central government in Bogotá appointed local government officials. The national congress allowed local government elections in 1986 and the change was ratified permanently in the 1991 federal constitution.

24 Frank Safford and Marco Palacios, Colombia: Fragmented Land, Divided Society (New York: Oxford University Press, 2002), p. 356.

25 See Garry Leech, “Fifty Years of Violence,” Colombia Journal Online, at http://www.colombiajournal.org/fiftyyearsofviolence.htm.

26 Ibid.

27 The Alliance for Progress was one of the Kennedy administration’s responses to the 1959 Cuban Revolution: A program of loans to encourage economic development and private enterprise in Latin America. For more on the program, see John Gerassi, The Great Fear in Latin America (New York: Collier Books, 1965).

28 Quote in Noam Chomsky, The New Military Humanism (Monroe, Maine: Common Courage Press, 1999), p. 50.

29 Lawrence Korb, quoted in Peter Dale Scott and Jonathan Marshall, Cocaine Politics: Drugs, Armies, and the CIA in Central America (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), p. 3.

30 All figures from “Los Estados Unidos y Colombia, 2003: Una mirada a las cifras,” Consultoria para los derechos humanos y desplazamiento (CODHES), available online at http://www.codhes.org.co.