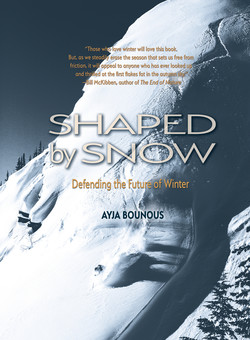

Читать книгу Shaped by Snow - Ayja Bounous - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

In such anxious reflection as this, I crossed the bridge, embarrassed by my discourtesy in having appeared before you without a New Year’s present … Just then by a happy chance water-vapour was condensed by the cold into snow, and specks of down fell here and there upon my coat, all with six corners and feathered radii. ’Pon my word, here was something smaller than any drop, yet with a pattern; here was the ideal New Year’s gift for the devotee of Nothing, the very thing for a mathematician to give, who has Nothing and receives Nothing, since it comes down from heaven and looks like a star.

—Johannes Kepler, The Six-Cornered Snowflake, 1611

In the winter of 1511, Brussels experienced such an intense series of snowstorms that the entire city shut down for almost six weeks. Instead of staying indoors, the residents took to the streets. They began to pick up the white stars that fell from the sky. They compressed the crystals, molding the snow into small, spherical shapes that fit comfortably in their palms. They made the snowballs larger and larger, stacking them on top of each other, decorating them with stones and twigs, buttons and cloth.

The result? Hundreds of snowmen lining the streets of Brussels.

If water is the key ingredient in the recipe for life, then snow is the zest that enhances the flavor. Snow forces life to be creative. Plants adapt to its seasonal pressures, figuring out ways to survive under what could be a few inches for a short amount of time, to a few feet for half a year. Some birds flee an area entirely when they sense snow in the air, while others drop their internal body temperature, shivering to stay warm. Reptiles and amphibians have yet to evolve the skills required to live actively in snow, sleeping the winter away instead. Many mammals hibernate as well, retreating into their dens to curl up in rich fur coats. Most, however, have figured out ways of continuing life during the winter.

In regions defined by snow, animal appendages become smaller while bodies become larger. Special kinds of fat develop during the food-rich summer months for energy storage during the winter. Pelts go from brown to gray to white, allowing camouflage. Some animals harvest the pelts of others, creating new fabrics to keep their bare skin warm. They build structures to protect themselves from the storms, and ignite fires for light and heat. They strap long, thin sticks to their feet and push themselves through the snow, the redistribution of weight preventing them from sinking too deep. This mode of transportation allows them to move as fast as the animals they hunt, helping them become more successful in the winter.

Snow sparks creativity. From forcing us to develop survival skills to inspiring us to create art, the six-pointed crystals have influenced humans for millennia. Snowfall requires us to work harder to stay warm and survive, but at times it releases us from our obligations and allows for leisure, as was the case in Brussels almost six hundred years ago.

Mathematician Johannes Kepler became intrigued with snowflakes in 1611. He was headed to a New Year’s party when he noticed snowflakes landing on his jacket. He marveled at their delicate structures, mystified by why each had six points. Kepler hypothesized a number of theories, but never figured out the reason behind their starry shapes. His obsession earned his book of musings, officially titled The Six-Cornered Snowflake, the nickname “Kepler’s Unsolved Problem.”

The human-snow relationship is an unsolved problem. Some of us love it, live for it, while others are indifferent or hate it. Some have never and will never see it. Too much carbon in the atmosphere will cause snow to disappear from certain landscapes, yet our global climate relies on its cooling and reflective properties. The watersheds of the American West depend on it. Many of the cultures around the Wasatch Mountain Range in Utah developed because of its presence during the winter. I am a product of it, since my four grandparents and my parents all met and created lives together through snow.

I love snow. I love how it drifts outside my bedroom window and the way it covers surfaces, rounding out corners and smoothing the landscape. I stay up late into the night so I can witness how it glows after the sun has set. I love how the world feels smaller and domed after a storm, like being inside a crystal ball. As a child I spent hours writing my name in snowfields, my footprints creating designs in the fleeting substance. I’d ski every day during the winter if I could.

My relationship to snow is an unsolved problem. Climate change is threatening snow in the American West, causing moisture to fall as rain. When I ski, I participate in an industry reliant upon fossil fuels for operation and transportation. When I travel to the mountains, ride chairlifts, or spend time in resort buildings, I release carbon emissions into the atmosphere, contributing to climate change.

My family has helped develop the ski industry in Northern Utah for almost one hundred years. Skiing is the reason I live the way I live and have the relationships I have. It has heavily influenced the way I appreciate the world. Snow is one of the reasons I care about the climate. But by skiing, I contribute to snow’s demise.

It’s uncertain what the future of snow will be. Even if the world experiences horrific climate change, drowning islands and cities, and mass desertification, snow won’t disappear completely. Water molecules will continue to crystallize and develop into snowflakes whenever the atmospheric conditions are right. But the way that we interact with snow will change. Organisms that have evolved around the constant, seasonal, or even intermittent presence of snow will be forced to adapt. Ecosystems reliant upon watersheds downstream of snow will struggle with drought. Communities, like mine, that have developed around the presence of snow will become scarce. We would no longer be able to line the streets with snowmen.

If climate change causes snow to stop falling, I won’t just mourn snow. I will mourn the places that snow shapes: alpine ecosystems, glaciers and mountain ranges, watersheds and rivers, our climate, the beautiful ski community I grew up a part of. I will mourn that my grandchildren and great-grandchildren won’t be able to catch snowflakes on their sleeves and marvel at their six points, or learn how to ski.

This book is my love song for snow; a way of sharing something that has shaped so much of this world and has made life on earth possible. It may also be my eulogy for snow; a way for me to remember it if it fades from my life, perhaps the only way for my great-grandchildren to experience it. This book is also a call to action: with my words, I fight for the survival of snow.