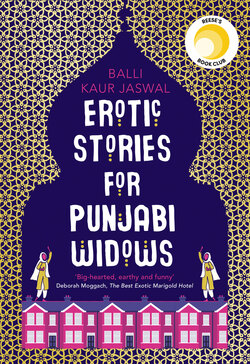

Читать книгу Erotic Stories for Punjabi Widows - Balli Kaur Jaswal, Balli Kaur Jaswal - Страница 9

Chapter Four

Оглавление‘There are no good men left in London,’ Olive remarked. ‘None.’ She surveyed the crowd from her perch at the bar while Nikki wiped down the counter, cursing the noisy blokes who had spent the past hour singing off-key rounds of football songs and winking sloppily at her.

‘There are plenty,’ Nikki assured her.

‘Plenty of duds,’ Olive said. ‘Unless you want me to date Steve with the Racist Grandfather.’

‘I would rather see you single for the rest of your life,’ Nikki said. Steve with the Racist Grandfather was a regular at the pub who prefaced his bigoted comments with, ‘as my grandfather would say …’ He considered this a foolproof way to absolve himself of being racist. ‘As my grandfather would say,’ he once told Nikki, ‘is your skin naturally that colour, or are you rusting? Of course, I would never say that. But my grandfather used to call khaki pants “Paki Pants” because he honestly thought the colour was named after their skin tone. He’s terrible, my grandfather.’

‘That guy’s all right,’ Nikki said, nodding at a tall man joining a group at a corner table. He took a seat and clapped one of his mates on the shoulder. Olive craned her neck to look. ‘Not too bad,’ Olive said. ‘He looks a bit like Lars. Remember him?’

‘You mean Laaawsh? He only told us a hundred times how to pronounce it correctly,’ Nikki said. He was a Swedish exchange student that Olive’s family had hosted when they were in Year Twelve. ‘That was the year I spent more time claiming to study at your house than ever.’ It was the only way she could get her parents’ permission to spend so many evenings at Olive’s house.

‘With my luck, that guy’s already taken,’ Olive said.

‘I’ll go do some investigative work,’ Nikki said. She made her rounds at the tables and floated towards him. ‘Can I get you anything?’ she asked.

‘Sure.’ As he gave his order she noticed the wedding ring shining on his finger.

‘Sorry,’ Nikki said when returned to Olive. She poured her friend a drink on the house and joined Olive on the other side of the bar once her shift was over. Olive sighed. ‘Maybe I should go for an arranged marriage. How was your sister’s date the other night?’

‘Disastrous,’ Nikki said. ‘The guy talked about himself the whole time and then made a fuss because they were served water without lemon slices. I think he was trying to prove to Mindi that he was accustomed to a certain type of service.’

‘That’s a shame.’

‘It’s a relief, actually. I was worried that she’d settle for the first eligible Punjabi bachelor who came along but she told me she gave him a polite and firm “no, thank you” at the end of the night.’

‘Maybe Mindi’s more influenced by you than she realizes,’ Olive said.

‘I thought so too but Auntie Geeta who suggested this fine young man gave Mum the cold shoulder at the shops the other day. Mindi felt terrible and called her up to apologize. Auntie Geeta guilted her into signing up for Punjabi Speed Dating. It’s really not Mindi’s thing but she’s going along with it.’

‘Oh, you never know who Mindi might meet or where. The odds are in her favour at speed dating. Fifteen men in one night? Sign me up. It could be really fun. If nothing else, she comes out of it having put herself out there. That’s more than I’m doing.’

‘It sounds like a nightmare to me. These are fifteen Punjabi men looking for a wife. When Mindi registered, she had to tell the organizers her caste, dietary preferences and rate her religiousness on a scale of one to ten.’

Olive laughed. ‘I’d be a minus three in any religion,’ she said. ‘I’d be a terrible candidate.’

‘Me too,’ Nikki said. ‘Mindi’s about a six or seven, although I think she’d claim to be more religious if it pleased the right man. I worry that she’s only doing this for people like Auntie Geeta.’

‘Well, she should be the least of your problems right now,’ Olive said. ‘You have to teach grannies the alphabet tomorrow.’

Nikki groaned. ‘Where do I start?’

‘I told you I have lots of books on literacy that you could borrow.’

‘For Year Seven students. These women are starting from scratch.’

‘You’re telling me they can’t read road signs? They can’t read the headline scrolling by when the news is on? How have they managed living in England all this time?’

‘I suppose they were always able to get by with their husbands’ help. For anything else, they could just speak in Punjabi.’

‘But your mum was never so dependent on your dad.’

‘My parents met at university in Delhi and Mum has her own livelihood. These women grew up in villages. Most couldn’t spell their own names in Punjabi, let alone English.’

‘I can’t imagine living my whole life like that,’ Olive said, taking a swig of her pint.

‘Do you remember those writing books we used to have when we were kids? How to do capital letters and cursive?’ Nikki asked.

‘The ones where you practise writing in the lines – penmanship books?’

‘Yes. Those would be useful.’

‘You can find them online,’ Olive said. ‘The school textbook publishers have a good catalogue. I can look out for them for you.’

‘I need something for tomorrow’s lesson though.’

‘Try one of the charity shops on King Street.’

After locking up, Nikki stayed back for drinks and then she and Olive stumbled out onto the glistening road, arms linked together like schoolgirls. Nikki took her phone from her pocket and typed a message to Mindi.

Hey sis! Found the man of your dreams yet? Does he starch his own turban and comb his own moustache or will that be one of your DUTIES?

She giggled and pressed Send.

Nikki woke in the afternoon, her head still spinning from the night before. She reached for her phone. There was a message from Mindi.

Drinking on a weeknight, Nik? Obviously if sending stupid messages at that hour.

Nikki wiped the blur from her eyes and wrote Mindi a reply.

U have such a huge stick up your bum

Mindi wrote back within seconds.

And u probably just woke up. Talk about bums. Grow up Nikki.

Nikki tossed the phone into her bag. It took her twice as long as usual to just get out of bed because her head felt so heavy. She winced at the squeaky sound of the shower tap and the sting of water on her skin. After getting dressed, she walked up the street to the Oxfam shop. The musty smell of ancient wool coats tickled her nose. Old school textbooks and worksheets sat on a bottom shelf, under the rows of popular novels that Nikki often browsed and bought. Here, Nikki finally woke up. The familiar comfort of books helped to dissolve her hangover.

Searching the shop, Nikki found a Scrabble game as well. A few tiles were missing but it would still be useful for teaching the alphabet. She went back to the shelf to see if there was anything there for her and while browsing, a title caught her eye. Beatrix Potter: Letters. She had a copy of this book at home but its accompanying book, The Journals and Sketches of Beatrix Potter, was hard to find. She had seen it in a used bookshop in Delhi on her pre-exams trip with Dad and Mum but her wanting it had sparked an argument. She distracted herself from the memory by turning her attention to the adjacent shelf. Another title leaped out at her. Red Velvet: Pleasurable Stories for Women. She picked up the book and flipped through the pages and some of the phrases that jumped out at her were:

He undressed her slowly with his eyes, and then deftly with his fingers.

Delia was basking naked in the summer sun in the privacy of her own garden but somewhere, Hunter was watching.

‘I didn’t come here to see you,’ she said haughtily. She spun on her heels to leave the office and she saw his manhood bulging through his trousers. He wanted to see her.

Nikki grinned and took the books to the cashier. Leaving the shop, she thought of the inscription she would pen in the Red Velvet book. Dear Mindi, I might not be as grown-up as you but I do know a bit more about certain adult rituals. Here’s a guide for you and your Dream Husband.

Nikki hauled the bag of books to the classroom and heaved them onto the desk. A sheet of paper had been taped onto it: Nikki do not move desks and chairs in this room – Kulwinder. The desks had all been rearranged into their original neat rows. A low growl in Nikki’s stomach reminded her that she hadn’t yet eaten, but before she left for the langar hall, she shifted the desks into a circle again.

The smell of dal and sweet jalebis mixed in the air with the clatter of utensils and voices. She took her tray through the line and was served roti, rice, dal and yoghurt. Finding an open space on the floor near a row of older women, Nikki recalled being about thirteen and attending prayers with her parents at the smaller Enfield gurdwara. She had needed something from the car and approached Dad – who was sitting with some men – to ask for the keys. People had turned and stared as she crossed the invisible divide that segregated the sexes even though there were no such rules in the langar hall. What did Mindi see in this world that she didn’t? All of the women seemed to end up the same – weary and shuffling their feet. Nikki watched as they trailed into the hall, adjusting their scarves, pausing every few moments to give an obligatory greeting to another community member. The group of ladies sitting next to her chattered away about each woman who walked in. They knew entire histories:

‘Chacko’s wife – she’s just had an operation, poor thing. She won’t be walking for a while. Her eldest son is taking care of her. You know the one I mean? She has two sons. This is the one who bought the electronics shop from his uncle. Doing very well. I saw him pushing her around the park in a wheelchair the other day.’

‘That woman over there is Nishu’s youngest sister isn’t it? They all have that same high forehead. I heard they had a terrible case of flooding in their house last year. They had to re-carpet the place and throw out a lot of furniture. Such a waste! They’d bought a new lounge set only six weeks before.’

‘Is that Dalvinder? I thought she was in Bristol visiting her cousin.’

Nikki’s eyes followed each woman as the commentary ran. She could barely keep up with this rapid stream of information and details. Then a woman that she recognized strode into the hall. Kulwinder. She noticed a drawing of breath from the little group next to her and their voices lowered to a hush.

‘Look at that one, marching in here like she’s a big boss. She’s been so stuck-up lately,’ said a middle-aged woman whose stiff green dupatta was pulled so low that it nearly concealed her face.

‘Lately? She’s always been Miss High and Mighty. I don’t know what gives her the right to be like that now.’

It didn’t surprise Nikki that they didn’t like Kulwinder. She listened closely.

‘Oh, don’t,’ a wrinkly older woman said. She pushed her wire-rimmed frames further up the bridge of her nose. ‘She’s had a rough time. We should be sympathetic.’

‘I tried that approach but she didn’t want my sympathy. She was downright rude to me,’ said Green Dupatta.

‘Buppy Kaur went through the same problems, but at least she still acknowledges us when we say “We’re sorry for your loss”. Kulwinder’s different. I saw her walking around the neighbourhood the other day. I waved at her and she just looked in the other direction and kept walking. How am I supposed to be kind to somebody like that?’

‘Buppy Kaur’s problems were similar, not the same,’ the woman with the glasses said. ‘Her daughter ran away with that boy from Trinidad. She’s still living; Kulwinder’s girl is dead.’

Nikki looked up in surprise. The women noticed her abrupt movement but they kept on talking.

‘Death is death,’ somebody else agreed. ‘It’s far worse.’

‘Nonsense,’ Green Dupatta scoffed. ‘Death is better than life if a girl doesn’t have her honour. Sometimes the younger generation needs this reminder.’

Somehow, Nikki felt that these words were directed at her. She looked up at the woman who said it and met an even, challenging gaze. The other women murmured their acknowledgement. Nikki found her food harder to swallow. She took a gulp of water and kept her head down.

The woman with the wire-rimmed glasses made eye contact with Nikki. ‘Hai, they’re not all terrible. There are plenty of respectable girls in Southall. It depends on how they’re raised, doesn’t it?’ she said. She gave Nikki an almost imperceptible nod.

‘This generation is selfish. If Maya had just considered what she was doing to her family, none of this would have happened,’ Green Dupatta continued. ‘And don’t forget about the damage she did to Tarampal’s property as well. She could have destroyed the whole place.’

The other women looked uncomfortable now. Like Nikki, they lowered their heads and focused on their dinners. In the sudden silence, Nikki could hear her own heart beating faster. Tarampal? Nikki wondered if they were referring to the same Tarampal from her writing classes. Nikki silently urged Green Dupatta to say more but without an attentive audience, she grew quiet as well.

Entering the community centre building afterwards, Nikki was lost in thought. The woman in the langar hall had appeared so certain when she spoke of death and honour. Nikki couldn’t imagine any offspring of Kulwinder’s getting caught up in some act of dangerous resistance as the women had implied. Then again, Kulwinder was so unyielding that perhaps her daughter had rebelled.

Laughter rang down the corridor, breaking her thoughts. Strange, she thought. There were no other classes on at the same time. As she made her way to the room, the noise became louder and she could hear a voice clearly speaking.

‘He puts his hand on her thigh as she’s driving the car and, as she’s driving, he moves his hand closer between her legs. She can’t concentrate on driving, so she tells him, “let me just get to a small side street”. He tells her – why do we have to wait?’

Nikki froze outside the door. It was Sheena’s voice. Another woman called out.

‘Chee, why is he so impatient? Can’t keep it in his pants until they get to a side street? She should punish him by driving him around the car park until his little balloon deflates.’

Another wave of laughter. Nikki threw open the door.

Sheena was sitting on the front desk with the book open in her hands and all the women were crowded around her. When they saw Nikki, they scurried back to their seats. The colour drained from Sheena’s face. ‘So sorry,’ she said to Nikki. ‘We saw that you had brought us books. I was just translating a story …’ She slid off the desk and went to join the ladies at their seats.

‘That book is mine. It’s private. It’s obviously not for any of you,’ Nikki said when she felt that she could speak. She reached into the bag and pulled out the workbooks. ‘These are for you.’ She tossed them onto the desk and put her head in her hands. The women were silent.

‘Why were you all here so early?’

‘You said seven o’clock,’ said Arvinder.

‘I said seven thirty, since that was the time you all preferred,’ Nikki said.

The women turned to look accusingly at Manjeet.

‘I remember her saying seven o’clock last week,’ Manjeet insisted. ‘I remember it.’

‘Turn up your hearing aid next time,’ Arvinder said.

‘I don’t need to,’ Manjeet said. She tucked her scarf behind her ear to reveal the hearing aid to the class. ‘This has never had a battery in it.’

‘Why would you wear a hearing aid if you didn’t need one?’ Nikki asked.

Manjeet dropped her head in embarrassment. ‘Completes the whole widow look,’ Sheena explained.

‘Oh,’ Nikki said. She waited for a further explanation from Manjeet but she simply nodded and stared at her hands.

Preetam raised her hand. ‘Excuse me, Nikki. Can we change the start time back to 7 p.m.?’

Nikki sighed. ‘I thought 7.30 worked better with your bus schedule.’

‘It does, but if we finish earlier, it means we can get home at a decent hour.’

‘Thirty minutes doesn’t make that much difference does it?’ Sheena asked.

‘It does for Anya and Kapil,’ Preetam said. ‘And what about Rajiv and Priyaani?’

Nikki guessed these were her grandchildren but then the other women let out a collective groan. ‘Those bloody idiots. One day they’re in love, the next day she is confiding to the servants that she wants to marry someone else,’ Sheena said. ‘Don’t change the time, Nikki. Preetam’s just wasting her time following a television series.’

‘I am not,’ Preetam said.

‘Then you’re wasting electricity,’ Arvinder chided. ‘Do you know how much our bill was last month?’ Preetam shrugged. ‘Of course you don’t,’ Arvinder muttered. ‘You waste everything because you’ve always had everything.’

‘Do you two share a home?’ Nikki asked. She noticed a resemblance. Both women were light-skinned, with the same thin lips and striking greyish brown eyes. ‘Sisters?’

‘Mother and daughter,’ Arvinder said, pointing to herself and then Preetam. ‘Seventeen years apart, but thank you for thinking that I’m that young.’

‘Or that Preetam’s that old,’ Sheena teased.

‘Have you always lived together?’ Nikki asked. She could not imagine a world where she would live with Mum into her senior citizen years and retain her sanity.

‘Only since my husband died,’ Preetam said. ‘How long has it been – hai!’ she suddenly cried out. ‘Three months.’ She took the edge of her dupatta and dabbed at the corners of her eyes.

‘Oh, enough with the theatrics,’ Arvinder said. ‘It’s been three years.’

‘But it’s still so fresh,’ Preetam moaned. ‘Has it really been that long?’

‘You know very well it has been,’ Arvinder said sternly. ‘I don’t know where you got this idea that widows have to cry and beat their chests every time their husbands are mentioned but it’s unnecessary.’

‘She got it from the evening dramas,’ Sheena said.

‘There. Another reason to cut back on the television,’ Arvinder said.

‘I think it’s very sweet,’ Manjeet said. ‘I want to be sad like that too. Did you faint at his funeral?’

‘Twice,’ Preetam said proudly. ‘And I begged them not to cremate him.’

‘I remember that,’ Sheena said. ‘You made a huge fuss before passing out and then you woke up and started all over again.’ She rolled her eyes at Nikki. ‘You have to do these things, see, otherwise people accuse you of being unfeeling.’

‘I know,’ Nikki said. After Dad died, Auntie Geeta had come over to visit, black rivulets of mascara running down her cheeks. She wanted to mourn with Mum and was surprised that Mum remained dry-eyed, having done her crying in private. When she noticed a bubbling pot of curry on the stove, she became indignant. ‘You’re eating? I had nothing after my husband died. My sons had to force it into my mouth.’ Feeling pressured, Mum refrained from eating the curry and then wolfed it down after Auntie Geeta left.

‘You are all lucky to be able to grieve like that,’ Manjeet said. ‘Women like me don’t get a funeral or any sort of ceremony.’

‘Now, now, Manjeet, don’t go putting it on yourself. There are no women like you. Just men like him,’ Arvinder said.

‘I don’t understand—’ Nikki said.

‘Are we going to do any work or is this another class of introductions?’ Tarampal interrupted. She shot Nikki a disapproving look.

‘We have less than an hour now,’ Nikki said. She handed the books out to the women. ‘There are some alphabet exercises in here. She gave Sheena a letter-writing worksheet she had printed off the internet.

The remainder of the lesson passed slowly and silently, with the women scrunching up their faces in concentration. Some looked tired after a few tries and put their pencils down. Nikki wanted to find out more about the widows but Tarampal’s presence kept her nervously on task. As soon as the clock struck 8.30, she told them they were dismissed and they filed out quietly, putting their books back on the desk. Sheena ducked past her and said nothing, clutching her letter in her hand.

The next lesson was on Thursday. All the women were promptly seated when Nikki arrived with an alphabet chart that she had found in another charity shop. ‘A is for apple,’ she said. They repeated ‘Apple’ after her. ‘B is for boy.’ ‘C is for cat.’ By the time they got to M, the chorus had faded. Nikki sighed and put down the chart.

‘I can’t teach you to write in any other way,’ she said. ‘We have to go through the basics.’

‘My grandchildren use these books and charts,’ sniffed Preetam. ‘It’s insulting.’

‘I don’t know what else to do,’ Nikki said.

‘You’re the teacher – don’t you know how to teach writing to adults?’

‘I thought we’d be writing stories. Not this,’ Nikki said. She picked up the chart and went back to the letters, and by the time they got to Z for zebra, the chorus was loud. There was a glimmer of hope – they were trying, at least.

‘Right. Now there are a few writing exercises so we can learn about how to form words,’ Nikki said. She flipped through the workbook and copied a few words on the board. As she turned, she heard urgent whispers but the women stopped talking when she was facing them again.

‘The best way to learn to spell words is to sound them out first. We’ll start with the word “cat.” Who wants to repeat after me? “Cat”.’

Preetam’s hand shot up. ‘Yes, go ahead, Bibi Preetam.’

‘What sorts of stories would you have us writing?’

Nikki sighed. ‘It’s going to be a long time before we can start writing stories, ladies. It’s really difficult unless you have a sense of how the words are spelled and how the grammar works.’

‘But Sheena can read and write in English.’

‘And I’m sure it took her a lot of practice, right, Sheena? When did you learn?’

‘I learned in school,’ Sheena said. ‘My family came to Britain when I was fourteen years old.’

‘That’s not what I mean,’ Preetam said. ‘I’m saying that if we tell Sheena our stories, she can put them in writing.’

Sheena looked pleased. ‘I could do that,’ she said to Nikki.

‘And then we could give each other advice on how to improve the stories.’

‘But how will you ever learn to write?’ Nikki asked. ‘Isn’t that why you signed up for these classes?’

The women shared a look. ‘We signed up for these classes because we wanted to fill our time,’ Manjeet said. ‘Whether it’s learning to write, or telling stories, it doesn’t matter. What matters is that we’re keeping busy.’ Nikki noticed she looked particularly sad when she said this. When she caught Nikki looking at her, she quickly smiled and dropped her gaze.

‘I’d rather be telling stories,’ said Arvinder. ‘I’ve survived all this time without reading and writing; what do I need it for now?’

There was resounding agreement. Nikki was torn. If the tedium of learning to write was discouraging these women, she should motivate them to keep going. But storytelling was so much more fun.

In the back, Tarampal called out, ‘I don’t like this idea. I am here to learn to write.’ She crossed her arms over her chest.

‘You do your ABC colouring books then,’ Arvinder muttered. Only Nikki heard her.

‘Here’s what we can do,’ Nikki said. ‘We’ll do a bit of writing and reading practice for every lesson, and then if you want to do some storytelling sessions, Sheena and I can transcribe your stories and we can share them with the class. One new story each lesson.’

‘Can we start today?’ Preetam asked.

Nikki looked at the clock. ‘We’ll go through vowels first, and then, yes, we can do some stories.’

Some women already knew A E I O U but others like Tarampal struggled with them. Everybody grumbled at her for holding back the rest of the class when Nikki quizzed them. ‘The A and the E are pronounced the same,’ Tarampal kept insisting. Nikki instructed Sheena to start transcribing in the back of the classroom while she worked with Tarampal.

‘English is such a stupid language,’ Tarampal said. ‘Nothing makes sense.’

‘You’re getting frustrated because it’s new. It will get easier,’ Nikki assured.

‘New? I’ve been in London for over twenty years.’

It still came as a mild shock to Nikki that these women knew so little after living here for longer than she had been alive. Tarampal caught her expression and nodded. ‘Tell me, why haven’t I picked up English? Because of the English.’ She said this triumphantly. ‘They haven’t made their country or their customs friendly to me. Now their language is just as unfriendly with these Ahh-Oooh sounds.’

In the back of the room, there was a rise of giggles and a squeal. Sheena was hunched over her paper, scribbling quickly while Arvinder whispered in her ear. Nikki turned her attention back to Tarampal and carefully said different words with vowels until Tarampal admitted to hearing the slightest difference between them. By the time they were finished, so was the lesson, but the women in the back of the room were still crowded around the desk and whispering urgently. Sheena continued writing, pausing every now and then to think of a correct word, or to rest her wrists. It was nine o’clock.

‘Class is dismissed,’ Nikki called out to the back. The women didn’t appear to have heard her. They continued chatting and Sheena dutifully transcribed. Tarampal crossed the room to pack up her bag. She tossed the women a look of contempt and muttered, ‘Bye,’ to Nikki.

Nikki felt her spirits lifted by the women and their renewed sense of focus. They wouldn’t learn to write this way but they were obviously so much keener on telling stories. As she made their way towards them, the women fell silent. Their faces were flushed. Some were hiding smiles. Sheena turned around.

‘It’s a surprise, Nikki,’ she said. ‘You can’t see. We’re not done yet, anyway.’

‘It’s time to lock up,’ Nikki said. ‘You’ll miss your bus.’

Reluctantly, the women rose from their seats and picked up their bags. They left the room in a buzz of whispers. In the empty classroom, Nikki put the tables back in their usual place, just as she’d been told to do by Kulwinder.

The light in the classroom in the community centre was still on. Kulwinder could see the window glowing as she walked out of the temple. She slowed down and considered what to do. Nikki had probably left the light on and if Kulwinder didn’t go up there to turn it off, Gurtaj Singh might decide that electricity was being wasted on classes for women. But she would not be safe entering that empty building. The phone call from the other night invaded her mind whenever she found herself alone. Before that, there had been two other warnings – one call which came only hours after she returned from her first intentional visit to the station and another one after her last visit. Both times, the police had offered little help, but her caller still felt the need to keep her in line.

She decided not to bother with the light. Walking briskly towards the bus stop she saw the women from the writing class in a huddle. Kulwinder did a silent roll call. There was Arvinder Kaur – so tall that she had to stoop like a giraffe to listen to the others. Her daughter Preetam was perpetually adjusting the lacy white dupatta on her head. So precious and vain compared to her mother. On the edge of the group, Manjeet Kaur spoke in furtive nods and smiles. Sheena Kaur was nowhere to be seen but she had probably sped home in her little red car. Tarampal Kaur had registered as well but she wasn’t part of the group. Her absence was a relief.

The women noticed Kulwinder approaching and they acknowledged her with quick smiles. Maybe they could explain why the light was still on. Perhaps Nikki was in there entertaining a lover? It wasn’t unheard of for youngsters in the neighbourhood to use these vacant rooms for their filthy interactions. In that case the lights would be off though wouldn’t they – but then again, who knew what this new generation found pleasurable?

‘Sat sri akal,’ she said, putting her hands together for all of them. They returned the gesture. ‘Sat sri akal,’ they murmured. In the glow of the streetlamp, they looked sheepish, as if caught stealing.

‘How are you, ladies?’

‘Very good, thanks,’ said Preetam Kaur.

‘Enjoying your writing classes?’

‘Yes.’ They were a rehearsed chorus. Kulwinder eyed them suspiciously.

‘Learning a lot?’ she asked.

A sly look passed between the women, just a flash, before Arvinder said, ‘Oh yes. We did a lot of learning today.’

The women beamed. Kulwinder considered asking them more. Perhaps they needed a reminder that their learning was the result of her clever initiative. I do everything for you, she used to tell Maya, sometimes with pride and at other times, with frustration. The women looked desperate to get back to their conversation. Kulwinder was reminded of Maya and her friends huddled together, their hushed conversation often punctuated with giggles. ‘What was so funny?’ Kulwinder would ask later, knowing the question was enough to make Maya dissolve into giggles again, and then Kulwinder couldn’t help laughing along. The memory was accompanied by a stabbing pain in her gut. What she would give to see her daughter’s smile again. She bade the women farewell and continued her journey. She had never been close to these women and she knew they had signed up for her classes for lack of anything else to do. She had loss in common with them, but losing a child was different. Nobody knew the ache of rage, guilt and profound sadness that Kulwinder carried with her every day.

This main road had some shadowy patches where walls of hedges and parked cars could easily hide a crouching assailant. She reached for her phone, wanting to ask Sarab to come and pick her up but standing still seemed just as risky. She set her sights on the junction of Queen Mary Road and marched onward, aware that her heart had started pounding. After the caller had hung up last night, she had sat up in bed, alert to every creak and shift in the house. She had drifted to sleep eventually but this morning, exhausted and alone, she found herself inexplicably furious, this time at Maya for putting her through all of this.

Laughter broke like fireworks into the air. Kulwinder whipped around. It was the women again. Manjeet waved but she pretended not to see. Kulwinder craned her neck as if she was checking something on the building. From this distance, the glow in the window reminded her of flames. She turned her back on the building and walked so briskly she nearly broke into a run.