Читать книгу Dreams From My Father - Barack Obama - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER TWO

THE ROAD TO THE embassy was choked with traffic: cars, motorcycles, tricycle rickshaws, buses and jitneys filled to twice their capacity, a procession of wheels and limbs all fighting for space in the midafternoon heat. We nudged forward a few feet, stopped, found an opening, stopped again. Our taxi driver shooed away a group of boys who were hawking gum and loose cigarettes, then barely avoided a motor scooter carrying an entire family on its back—father, mother, son, and daughter all leaning as one into a turn, their mouths wrapped with handkerchiefs to blunt the exhaust, a family of bandits. Along the side of the road, wizened brown women in faded brown sarongs stacked straw baskets high with ripening fruit, and a pair of mechanics squatted before their open-air garage, lazily brushing away flies as they took an engine apart. Behind them, the brown earth dipped into a smoldering dump where a pair of round-headed tots frantically chased a scrawny black hen. The children slipped in the mud and corn husks and banana leaves, squealing with pleasure, until they disappeared down the dirt road beyond.

Things eased up once we hit the highway, and the taxi dropped us off in front of the embassy, where a pair of smartly dressed Marines nodded in greeting. Inside the courtyard, the clamor of the street was replaced by the steady rhythm of gardening clippers. My mother’s boss was a portly black man with closely cropped hair sprinkled gray at the temples. An American flag draped down in rich folds from the pole beside his desk. He reached out and offered a firm handshake: “How are you, young man?” He smelled of after-shave and his starched collar cut hard into his neck. I stood at attention as I answered his questions about the progress of my studies. The air in the office was cool and dry, like the air of mountain peaks: the pure and heady breeze of privilege.

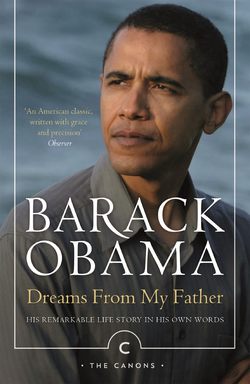

Our audience over, my mother sat me down in the library while she went off to do some work. I finished my comic books and the homework my mother had made me bring before climbing out of my chair to browse through the stacks. Most of the books held little interest for a nine-year-old boy—World Bank reports, geological surveys, five-year development plans. But in one corner I found a collection of Life magazines neatly displayed in clear plastic binders. I thumbed through the glossy advertisements—Goodyear Tires and Dodge Fever, Zenith TV (“Why not the best?”) and Campbell’s Soup (“Mm-mm good!”), men in white turtlenecks pouring Seagram’s over ice as women in red miniskirts looked on admiringly—and felt vaguely reassured. When I came upon a news photograph, I tried to guess the subject of the story before reading the caption. The photograph of French children dashing over cobblestoned streets: that was a happy scene, a game of hide-and-go-seek after a day of schoolbooks and chores; their laughter spoke of freedom. The photograph of a Japanese woman cradling a young, naked girl in a shallow tub: that was sad; the girl was sick, her legs twisted, her head fallen back against the mother’s breast, the mother’s face tight with grief, perhaps she blamed herself….

Eventually I came across a photograph of an older man in dark glasses and a raincoat walking down an empty road. I couldn’t guess what this picture was about; there seemed nothing unusual about the subject. On the next page was another photograph, this one a close-up of the same man’s hands. They had a strange, unnatural pallor, as if blood had been drawn from the flesh. Turning back to the first picture, I now saw that the man’s crinkly hair, his heavy lips and broad, fleshy nose, all had this same uneven, ghostly hue.

He must be terribly sick, I thought. A radiation victim, maybe, or an albino—I had seen one of those on the street a few days before, and my mother had explained about such things. Except when I read the words that went with the picture, that wasn’t it at all. The man had received a chemical treatment, the article explained, to lighten his complexion. He had paid for it with his own money. He expressed some regret about trying to pass himself off as a white man, was sorry about how badly things had turned out. But the results were irreversible. There were thousands of people like him, black men and women back in America who’d undergone the same treatment in response to advertisements that promised happiness as a white person.

I felt my face and neck get hot. My stomach knotted; the type began to blur on the page. Did my mother know about this? What about her boss—why was he so calm, reading through his reports a few feet down the hall? I had a desperate urge to jump out of my seat, to show them what I had learned, to demand some explanation or assurance. But something held me back. As in a dream, I had no voice for my newfound fear. By the time my mother came to take me home, my face wore a smile and the magazines were back in their proper place. The room, the air, was quiet as before.

We had lived in Indonesia for over three years by that time, the result of my mother’s marriage to an Indonesian named Lolo, another student she had met at the University of Hawaii. His name meant “crazy” in Hawaiian, which tickled Gramps to no end, but the meaning didn’t suit the man, for Lolo possessed the good manners and easy grace of his people. He was short and brown, handsome, with thick black hair and features that could have as easily been Mexican or Samoan as Indonesian; his tennis game was good, his smile uncommonly even, and his temperament imperturbable. For two years, from the time I was four until I was six, he endured endless hours of chess with Gramps and long wrestling sessions with me. When my mother sat me down one day to tell me that Lolo had proposed and wanted us to move with him to a faraway place, I wasn’t surprised and expressed no objections. I did ask her if she loved him—I had been around long enough to know such things were important. My mother’s chin trembled, as it still does when she’s fighting back tears, and she pulled me into a long hug that made me feel very brave, although I wasn’t sure why.

Lolo left Hawaii quite suddenly after that, and my mother and I spent months in preparation—passports, visas, plane tickets, hotel reservations, an endless series of shots. While we packed, my grandfather pulled out an atlas and ticked off the names in Indonesia’s island chain: Java, Borneo, Sumatra, Bali. He remembered some of the names, he said, from reading Joseph Conrad as a boy. The Spice Islands, they were called back then, enchanted names, shrouded in mystery. “Says here they still got tigers over there,” he said. “And orangutangs.” He looked up from the book and his eyes widened. “Says here they even got headhunters!” Meanwhile, Toot called the State Department to find out if the country was stable. Whoever she spoke to there informed her that the situation was under control. Still, she insisted that we pack several trunks full of foodstuffs: Tang, powdered milk, cans of sardines. “You never know what these people will eat,” she said firmly. My mother sighed, but Toot tossed in several boxes of candy to win me over to her side.

Finally, we boarded a Pan Am jet for our flight around the globe. I wore a long-sleeved white shirt and a gray clip-on tie, and the stewardesses plied me with puzzles and extra peanuts and a set of metal pilot’s wings that I wore over my breast pocket. On a three-day stopover in Japan, we walked through bone-chilling rains to see the great bronze Buddha at Kamakura and ate green tea ice cream on a ferry that passed through high mountain lakes. In the evenings my mother studied flash cards. Walking off the plane in Djakarta, the tarmac rippling with heat, the sun bright as a furnace, I clutched her hand, determined to protect her from whatever might come.

Lolo was there to greet us, a few pounds heavier, a bushy mustache now hovering over his smile. He hugged my mother, hoisted me up into the air, and told us to follow a small, wiry man who was carrying our luggage straight past the long line at customs and into an awaiting car. The man smiled cheerfully as he lifted the bags into the trunk, and my mother tried to say something to him but the man just laughed and nodded his head. People swirled around us, speaking rapidly in a language I didn’t know, smelling unfamiliar. For a long time we watched Lolo talk to a group of brown-uniformed soldiers. The soldiers had guns in their holsters, but they appeared to be in a jovial mood, laughing at something that Lolo had said. When Lolo finally joined us, my mother asked if the soldiers needed to check through our bags.

“Don’t worry … that’s been all taken care of,” Lolo said, climbing into the driver’s seat. “Those are friends of mine.”

The car was borrowed, he told us, but he had bought a brand-new motorcycle—a Japanese make, but good enough for now. The new house was finished; just a few touch-ups remained to be done. I was already enrolled in a nearby school, and the relatives were anxious to meet us. As he and my mother talked, I stuck my head out the backseat window and stared at the passing landscape, brown and green uninterrupted, villages falling back into forest, the smell of diesel oil and wood smoke. Men and women stepped like cranes through the rice paddies, their faces hidden by their wide straw hats. A boy, wet and slick as an otter, sat on the back of a dumb-faced water buffalo, whipping its haunch with a stick of bamboo. The streets became more congested, small stores and markets and men pulling carts loaded with gravel and timber, then the buildings grew taller, like buildings in Hawaii—Hotel Indonesia, very modern, Lolo said, and the new shopping center, white and gleaming—but only a few were higher than the trees that now cooled the road. When we passed a row of big houses with high hedges and sentry posts, my mother said something I couldn’t entirely make out, something about the government and a man named Sukarno.

“Who’s Sukarno?” I shouted from the backseat, but Lolo appeared not to hear me. Instead, he touched my arm and motioned ahead of us. “Look,” he said, pointing upward. There, standing astride the road, was a towering giant at least ten stories tall, with the body of a man and the face of an ape.

“That’s Hanuman,” Lolo said as we circled the statue, “the monkey god.” I turned around in my seat, mesmerized by the solitary figure, so dark against the sun, poised to leap into the sky as puny traffic swirled around its feet. “He’s a great warrior,” Lolo said firmly. “Strong as a hundred men. When he fights the demons, he’s never defeated.”

The house was in a still-developing area on the outskirts of town. The road ran over a narrow bridge that spanned a wide brown river; as we passed, I could see villagers bathing and washing clothes along the steep banks below. The road then turned from tarmac to gravel to dirt as it wound past small stores and whitewashed bungalows until it finally petered out into the narrow footpaths of the kampong. The house itself was modest stucco and red tile, but it was open and airy, with a big mango tree in the small courtyard in front. As we passed through the gate, Lolo announced that he had a surprise for me; but before he could explain we heard a deafening howl from high up in the tree. My mother and I jumped back with a start and saw a big, hairy creature with a small, flat head and long, menacing arms drop onto a low branch.

“A monkey!” I shouted.

“An ape,” my mother corrected.

Lolo drew a peanut from his pocket and handed it to the animal’s grasping fingers. “His name is Tata,” he said. “I brought him all the way from New Guinea for you.”

I started to step forward to get a closer look, but Tata threatened to lunge, his dark-ringed eyes fierce and suspicious. I decided to stay where I was.

“Don’t worry,” Lolo said, handing Tata another peanut. “He’s on a leash. Come—there’s more.”

I looked up at my mother, and she gave me a tentative smile. In the backyard, we found what seemed like a small zoo: chickens and ducks running every which way, a big yellow dog with a baleful howl, two birds of paradise, a white cockatoo, and finally two baby crocodiles, half submerged in a fenced-off pond toward the edge of the compound. Lolo stared down at the reptiles. “There were three,” he said, “but the biggest one crawled out through a hole in the fence. Slipped into somebody’s rice field and ate one of the man’s ducks. We had to hunt it by torchlight.”

There wasn’t much light left, but we took a short walk down the mud path into the village. Groups of giggling neighborhood children waved from their compounds, and a few barefoot old men came up to shake our hands. We stopped at the common, where one of Lolo’s men was grazing a few goats, and a small boy came up beside me holding a dragonfly that hovered at the end of a string. When we returned to the house, the man who had carried our luggage was standing in the backyard with a rust-colored hen tucked under his arm and a long knife in his right hand. He said something to Lolo, who nodded and called over to my mother and me. My mother told me to wait where I was and sent Lolo a questioning glance.

“Don’t you think he’s a little young?”

Lolo shrugged and looked down at me. “The boy should know where his dinner is coming from. What do you think, Barry?” I looked at my mother, then turned back to face the man holding the chicken. Lolo nodded again, and I watched the man set the bird down, pinning it gently under one knee and pulling its neck out across a narrow gutter. For a moment the bird struggled, beating its wings hard against the ground, a few feathers dancing up with the wind. Then it grew completely still. The man pulled the blade across the bird’s neck in a single smooth motion. Blood shot out in a long, crimson ribbon. The man stood up, holding the bird far away from his body, and suddenly tossed it high into the air. It landed with a thud, then struggled to its feet, its head lolling grotesquely against its side, its legs pumping wildly in a wide, wobbly circle. I watched as the circle grew smaller, the blood trickling down to a gurgle, until finally the bird collapsed, lifeless on the grass.

Lolo rubbed his hand across my head and told me and my mother to go wash up before dinner. The three of us ate quietly under a dim yellow bulb—chicken stew and rice, and then a dessert of red, hairy-skinned fruit so sweet at the center that only a stomachache could make me stop. Later, lying alone beneath a mosquito net canopy, I listened to the crickets chirp under the moonlight and remembered the last twitch of life that I’d witnessed a few hours before. I could barely believe my good fortune.

“The first thing to remember is how to protect yourself.”

Lolo and I faced off in the backyard. A day earlier, I had shown up at the house with an egg-sized lump on the side of my head. Lolo had looked up from washing his motorcycle and asked me what had happened, and I told him about my tussle with an older boy who lived down the road. The boy had run off with my friend’s soccer ball, I said, in the middle of our game. When I chased after him, the boy picked up a rock. It wasn’t fair, I said, my voice choking with aggrievement. He had cheated.

Lolo had parted my hair with his fingers and silently examined the wound. “It’s not bleeding,” he said finally, before returning to his chrome.

I thought that had ended the matter. But when he came home from work the next day, he had with him two pairs of boxing gloves. They smelled of new leather, the larger pair black, the smaller pair red, the laces tied together and thrown over his shoulder.

He now finished tying the laces on my gloves and stepped back to examine his handiwork. My hands dangled at my sides like bulbs at the ends of thin stalks. He shook his head and raised the gloves to cover my face.

“There. Keep your hands up.” He adjusted my elbows, then crouched into a stance and started to bob. “You want to keep moving, but always stay low—don’t give them a target. How does that feel?” I nodded, copying his movements as best I could. After a few minutes, he stopped and held his palm up in front of my nose.

“Okay,” he said. “Let’s see your swing.”

This I could do. I took a step back, wound up, and delivered my best shot. His hand barely wobbled.

“Not bad,” Lolo said. He nodded to himself, his expression unchanged. “Not bad at all. Agh, but look where your hands are now. What did I tell you? Get them up….”

I raised my arms, throwing soft jabs at Lolo’s palm, glancing up at him every so often and realizing how familiar his face had become after our two years together, as familiar as the earth on which we stood. It had taken me less than six months to learn Indonesia’s language, its customs, and its legends. I had survived chicken pox, measles, and the sting of my teachers’ bamboo switches. The children of farmers, servants, and low-level bureaucrats had become my best friends, and together we ran the streets morning and night, hustling odd jobs, catching crickets, battling swift kites with razor-sharp lines—the loser watched his kite soar off with the wind, and knew that somewhere other children had formed a long wobbly train, their heads toward the sky, waiting for their prize to land. With Lolo, I learned how to eat small green chill peppers raw with dinner (plenty of rice), and, away from the dinner table, I was introduced to dog meat (tough), snake meat (tougher), and roasted grasshopper (crunchy). Like many Indonesians, Lolo followed a brand of Islam that could make room for the remnants of more ancient animist and Hindu faiths. He explained that a man took on the powers of whatever he ate: One day soon, he promised, he would bring home a piece of tiger meat for us to share.

That’s how things were, one long adventure, the bounty of a young boy’s life. In letters to my grandparents, I would faithfully record many of these events, confident that more civilizing packages of chocolate and peanut butter would surely follow. But not everything made its way into my letters; some things I found too difficult to explain. I didn’t tell Toot and Gramps about the face of the man who had come to our door one day with a gaping hole where his nose should have been: the whistling sound he made as he asked my mother for food. Nor did I mention the time that one of my friends told me in the middle of recess that his baby brother had died the night before of an evil spirit brought in by the wind—the terror that danced in my friend’s eyes for the briefest of moments before he let out a strange laugh and punched my arm and broke off into a breathless run. There was the empty look on the faces of farmers the year the rains never came, the stoop in their shoulders as they wandered barefoot through their barren, cracked fields, bending over every so often to crumble earth between their fingers; and their desperation the following year when the rains lasted for over a month, swelling the river and fields until the streets gushed with water and swept as high as my waist and families scrambled to rescue their goats and their hens even as chunks of their huts washed away.

The world was violent, I was learning, unpredictable and often cruel. My grandparents knew nothing about such a world, I decided; there was no point in disturbing them with questions they couldn’t answer. Sometimes, when my mother came home from work, I would tell her the things I had seen or heard, and she would stroke my forehead, listening intently, trying her best to explain what she could. I always appreciated the attention—her voice, the touch of her hand, defined all that was secure. But her knowledge of floods and exorcisms and cockfights left much to be desired. Everything was as new to her as it was to me, and I would leave such conversations feeling that my questions had only given her unnecessary cause for concern.

So it was to Lolo that I turned for guidance and instruction. He didn’t talk much, but he was easy to be with. With his family and friends he introduced me as his son, but he never pressed things beyond matter-of-fact advice or pretended that our relationship was more than it was. I appreciated this distance; it implied a manly trust. And his knowledge of the world seemed inexhaustible. Not just how to change a flat tire or open in chess. He knew more elusive things, ways of managing the emotions I felt, ways to explain fate’s constant mysteries.

Like how to deal with beggars. They seemed to be everywhere, a gallery of ills—men, women, children, in tattered clothing matted with dirt, some without arms, others without feet, victims of scurvy or polio or leprosy walking on their hands or rolling down the crowded sidewalks in jerry-built carts, their legs twisted behind them like contortionists’. At first, I watched my mother give over her money to anyone who stopped at our door or stretched out an arm as we passed on the streets. Later, when it became clear that the tide of pain was endless, she gave more selectively, learning to calibrate the levels of misery. Lolo thought her moral calculations endearing but silly, and whenever he caught me following her example with the few coins in my possession, he would raise his eyebrows and take me aside.

“How much money do you have?” he would ask.

I’d empty my pocket. “Thirty rupiah.”

“How many beggars are there on the street?”

I tried to imagine the number that had come by the house in the last week. “You see?” he said, once it was clear I’d lost count. “Better to save your money and make sure you don’t end up on the street yourself.”

He was the same way about servants. They were mostly young villagers newly arrived in the city, often working for families not much better off than themselves, sending money to their people back in the country or saving enough to start their own businesses. If they had ambition, Lolo was willing to help them get their start, and he would generally tolerate their personal idiosyncrasies: for over a year, he employed a good-natured young man who liked to dress up as a woman on weekends—Lolo loved the man’s cooking. But he would fire the servants without compunction if they were clumsy, forgetful, or otherwise cost him money; and he would be baffled when either my mother or I tried to protect them from his judgment.

“Your mother has a soft heart,” Lolo would tell me one day after my mother tried to take the blame for knocking a radio off the dresser. “That’s a good thing in a woman. But you will be a man someday, and a man needs to have more sense.”

It had nothing to do with good or bad, he explained, like or dislike. It was a matter of taking life on its own terms.

I felt a hard knock to the jaw, and looked up at Lolo’s sweating face.

“Pay attention. Keep your hands up.”

We sparred for another half hour before Lolo decided it was time for a rest. My arms burned; my head flashed with a dull, steady throb. We took a jug full of water and sat down near the crocodile pond.

“Tired?” he asked me.

I slumped forward, barely nodding. He smiled, and rolled up one of his pant legs to scratch his calf. I noticed a series of indented scars that ran from his ankle halfway up his shin.

“What are those?”

“Leech marks,” he said. “From when I was in New Guinea. They crawl inside your army boots while you’re hiking through the swamps. At night, when you take off your socks, they’re stuck there, fat with blood. You sprinkle salt on them and they die, but you still have to dig them out with a hot knife.”

I ran my finger over one of the oval grooves. It was smooth and hairless where the skin had been singed. I asked Lolo if it had hurt.

“Of course it hurt,” he said, taking a sip from the jug. “Sometimes you can’t worry about hurt. Sometimes you worry only about getting where you have to go.”

We fell silent, and I watched him out of the corner of my eye. I realized that I had never heard him talk about what he was feeling. I had never seen him really angry or sad. He seemed to inhabit a world of hard surfaces and well-defined thoughts. A queer notion suddenly sprang into my head.

“Have you ever seen a man killed?” I asked him.

He glanced down, surprised by the question.

“Have you?” I asked again.

“Yes,” he said.

“Was it bloody?”

“Yes.”

I thought for a moment. “Why was the man killed? The one you saw?”

“Because he was weak.”

“That’s all?”

Lolo shrugged and rolled his pant leg back down. “That’s usually enough. Men take advantage of weakness in other men. They’re just like countries in that way. The strong man takes the weak man’s land. He makes the weak man work in his fields. If the weak man’s woman is pretty, the strong man will take her.” He paused to take another sip of water, then asked, “Which would you rather be?”

I didn’t answer, and Lolo squinted up at the sky. “Better to be strong,” he said finally, rising to his feet. “If you can’t be strong, be clever and make peace with someone who’s strong. But always better to be strong yourself. Always.”

My mother watched us from inside the house, propped up at her desk grading papers. What are they talking about? she wondered to herself. Blood and guts, probably; swallowing nails. Cheerful, manly things.

She laughed aloud, then caught herself. That wasn’t fair. She really was grateful for Lolo’s solicitude toward me. He wouldn’t have treated his own son very differently. She knew that she was lucky for Lolo’s basic kindness. She set her papers aside and watched me do push-ups. He’s growing so fast, she thought. She tried to picture herself on the day of our arrival, a mother of twenty-four with a child in tow, married to a man whose history, whose country, she barely knew. She had known so little then, she realized now, her innocence carried right along with her American passport. Things could have turned out worse. Much worse.

She had expected it to be difficult, this new life of hers. Before leaving Hawaii, she had tried to learn all she could about Indonesia: the population, fifth in the world, with hundreds of tribes and dialects; the history of colonialism, first the Dutch for over three centuries, then the Japanese during the war, seeking control over vast stores of oil, metal, and timber; the fight for independence after the war and the emergence of a freedom fighter named Sukarno as the country’s first president. Sukarno had recently been replaced, but all the reports said it had been a bloodless coup, and that the people supported the change. Sukarno had grown corrupt, they said; he was a demagogue, totalitarian, too comfortable with the Communists.

A poor country, underdeveloped, utterly foreign—this much she had known. She was prepared for the dysentery and fevers, the cold water baths and having to squat over a hole in the ground to pee, the electricity’s going out every few weeks, the heat and endless mosquitoes. Nothing more than inconveniences, really, and she was tougher than she looked, tougher than even she had known herself to be. And anyway, that was part of what had drawn her to Lolo after Barack had left, the promise of something new and important, helping her husband rebuild a country in a charged and challenging place beyond her parents’ reach.

But she wasn’t prepared for the loneliness. It was constant, like a shortness of breath. There was nothing definite that she could point to, really. Lolo had welcomed her warmly and gone out of his way to make her feel at home, providing her with whatever creature comforts he could afford. His family had treated her with tact and generosity, and treated her son as one of their own.

Still, something had happened between her and Lolo in the year that they had been apart. In Hawaii he had been so full of life, so eager with his plans. At night when they were alone, he would tell her about growing up as a boy during the war, watching his father and eldest brother leave to join the revolutionary army, hearing the news that both had been killed and everything lost, the Dutch army’s setting their house aflame, their flight into the countryside, his mother’s selling her gold jewelry a piece at a time in exchange for food. Things would be changing now that the Dutch had been driven out, Lolo had told her; he would return and teach at the university, be a part of that change.

He didn’t talk that way anymore. In fact, it seemed as though he barely spoke to her at all, only out of necessity or when spoken to, and even then only of the task at hand, repairing a leak or planning a trip to visit some distant cousin. It was as if he had pulled into some dark hidden place, out of reach, taking with him the brightest part of himself. On some nights, she would hear him up after everyone else had gone to bed, wandering through the house with a bottle of imported whiskey, nursing his secrets. Other nights he would tuck a pistol under his pillow before falling off to sleep. Whenever she asked him what was wrong, he would gently rebuff her, saying he was just tired. It was as if he had come to mistrust words somehow. Words, and the sentiments words carried.

She suspected these problems had something to do with Lolo’s job. He was working for the army as a geologist, surveying roads and tunnels, when she arrived. It was mind-numbing work that didn’t pay very much; the refrigerator alone cost two months’ salary. And now with a wife and child to provide for … no wonder he was depressed. She hadn’t traveled all this way to be a burden, she decided. She would carry her own weight.

She found herself a job right away teaching English to Indonesian businessmen at the American embassy, part of the U.S. foreign aid package to developing countries. The money helped but didn’t relieve her loneliness. The Indonesian businessmen weren’t much interested in the niceties of the English language, and several made passes at her. The Americans were mostly older men, careerists in the State Department, the occasional economist or journalist who would mysteriously disappear for months at a time, their affiliation or function in the embassy never quite clear. Some of them were caricatures of the ugly American, prone to making jokes about Indonesians until they found out that she was married to one, and then they would try to play it off—Don’t take Jim too seriously, the heat’s gotten to him, how’s your son by the way, fine, fine boy.

These men knew the country, though, or parts of it anyway, the closets where the skeletons were buried. Over lunch or casual conversation they would share with her things she couldn’t learn in the published news reports. They explained how Sukarno had frayed badly the nerves of a U.S. government already obsessed with the march of communism through Indochina, what with his nationalist rhetoric and his politics of nonalignment—he was as bad as Lumumba or Nasser, only worse, given Indonesia’s strategic importance. Word was that the CIA had played a part in the coup, although nobody knew for sure. More certain was the fact that after the coup the military had swept the countryside for supposed Communist sympathizers. The death toll was anybody’s guess: a few hundred thousand, maybe; half a million. Even the smart guys at the Agency had lost count.

Innuendo, half-whispered asides; that’s how she found out that we had arrived in Djakarta less than a year after one of the more brutal and swift campaigns of suppression in modern times. The idea frightened her, the notion that history could be swallowed up so completely, the same way the rich and loamy earth could soak up the rivers of blood that had once coursed through the streets; the way people could continue about their business beneath giant posters of the new president as if nothing had happened, a nation busy developing itself. As her circle of Indonesian friends widened, a few of them would be willing to tell her other stories—about the corruption that pervaded government agencies, the shakedowns by police and the military, entire industries carved out for the president’s family and entourage. And with each new story, she would go to Lolo in private and ask him: “Is it true?”

He would never say. The more she asked, the more steadfast he became in his good-natured silence. “Why are you worrying about such talk?” he would ask her. “Why don’t you buy a new dress for the party?” She had finally complained to one of Lolo’s cousins, a pediatrician who had helped look after Lolo during the war.

“You don’t understand,” the cousin had told her gently.

“Understand what?”

“The circumstances of Lolo’s return. He hadn’t planned on coming back from Hawaii so early, you know. During the purge, all students studying abroad had been summoned without explanation, their passports revoked. When Lolo stepped off the plane, he had no idea of what might happen next. We couldn’t see him; the army officials took him away and questioned him. They told him that he had just been conscripted and would be going to the jungles of New Guinea for a year. And he was one of the lucky ones. Students studying in Eastern Bloc countries did much worse. Many of them are still in jail. Or vanished.

“You shouldn’t be too hard on Lolo,” the cousin repeated. “Such times are best forgotten.”

My mother had left the cousin’s house in a daze. Outside, the sun was high, the air full of dust, but instead of taking a taxi home, she began to walk without direction. She found herself in a wealthy neighborhood where the diplomats and generals lived in sprawling houses with tall wrought-iron gates. She saw a woman in bare feet and a tattered shawl wandering through an open gate and up the driveway, where a group of men were washing a fleet of Mercedes-Benzes and Land Rovers. One of the men shouted at the woman to leave, but the woman stood where she was, a bony arm stretched out before her, her face shrouded in shadow. Another man finally dug in his pocket and threw out a handful of coins. The woman ran after the coins with terrible speed, checking the road suspiciously as she gathered them into her bosom.

Power. The word fixed in my mother’s mind like a curse. In America, it had generally remained hidden from view until you dug beneath the surface of things; until you visited an Indian reservation or spoke to a black person whose trust you had earned. But here power was undisguised, indiscriminate, naked, always fresh in the memory. Power had taken Lolo and yanked him back into line just when he thought he’d escaped, making him feel its weight, letting him know that his life wasn’t his own. That’s how things were; you couldn’t change it, you could just live by the rules, so simple once you learned them. And so Lolo had made his peace with power, learned the wisdom of forgetting; just as his brother-in-law had done, making millions as a high official in the national oil company; just as another brother had tried to do, only he had miscalculated and was now reduced to stealing pieces of silverware whenever he came for a visit, selling them later for loose cigarettes.

She remembered what Lolo had told her once when her constant questioning had finally touched a nerve. “Guilt is a luxury only foreigners can afford,” he had said. “Like saying whatever pops into your head.” She didn’t know what it was like to lose everything, to wake up and feel her belly eating itself. She didn’t know how crowded and treacherous the path to security could be. Without absolute concentration, one could easily slip, tumble backward.

He was right, of course. She was a foreigner, middle-class and white and protected by her heredity whether she wanted protection or not. She could always leave if things got too messy. That possibility negated anything she might say to Lolo; it was the unbreachable barrier between them. She looked out the window now and saw that Lolo and I had moved on, the grass flattened where the two of us had been. The sight made her shudder slightly, and she rose to her feet, filled with a sudden panic.

Power was taking her son.

Looking back, I’m not sure that Lolo ever fully understood what my mother was going through during these years, why the things he was working so hard to provide for her seemed only to increase the distance between them. He was not a man to ask himself such questions. Instead, he maintained his concentration, and over the period that we lived in Indonesia, he proceeded to climb. With the help of his brother-in-law, he landed a new job in the government relations office of an American oil company. We moved to a house in a better neighborhood; a car replaced the motorcycle; a television and hi-fi replaced the crocodiles and Tata, the ape; Lolo could sign for our dinners at a company club. Sometimes I would overhear him and my mother arguing in their bedroom, usually about her refusal to attend his company dinner parties, where American businessmen from Texas and Louisiana would slap Lolo’s back and boast about the palms they had greased to obtain the new offshore drilling rights, while their wives complained to my mother about the quality of Indonesian help. He would ask her how it would look for him to go alone, and remind her that these were her own people, and my mother’s voice would rise to almost a shout.

They are not my people.

Such arguments were rare, though; my mother and Lolo would remain cordial through the birth of my sister, Maya, through the separation and eventual divorce, up until the last time I saw Lolo, ten years later, when my mother helped him travel to Los Angeles to treat a liver ailment that would kill him at the age of fifty-one. What tension I noticed had mainly to do with the gradual shift in my mother’s attitude toward me. She had always encouraged my rapid acculturation in Indonesia: It had made me relatively self-sufficient, undemanding on a tight budget, and extremely well mannered when compared to other American children. She had taught me to disdain the blend of ignorance and arrogance that too often characterized Americans abroad. But she now had learned, just as Lolo had learned, the chasm that separated the life chances of an American from those of an Indonesian. She knew which side of the divide she wanted her child to be on. I was an American, she decided, and my true life lay elsewhere.

Her initial efforts centered on education. Without the money to send me to the International School, where most of Djakarta’s foreign children went, she had arranged from the moment of our arrival to supplement my Indonesian schooling with lessons from a U.S. correspondence course.

Her efforts now redoubled. Five days a week, she came into my room at four in the morning, force-fed me breakfast, and proceeded to teach me my English lessons for three hours before I left for school and she went to work. I offered stiff resistance to this regimen, but in response to every strategy I concocted, whether unconvincing (“My stomach hurts”) or indisputably true (my eyes kept closing every five minutes), she would patiently repeat her most powerful defense:

“This is no picnic for me either, buster.”

Then there were the periodic concerns with my safety, the voice of my grandmother ascendant. I remember coming home after dark one day to find a large search party of neighbors that had been assembled in our yard. My mother didn’t look happy, but she was so relieved to see me that it took her several minutes to notice a wet sock, brown with mud, wrapped around my forearm.

“What’s that?”

“What?”

“That. Why do you have a sock wrapped around your arm?”

“I cut myself.”

“Let’s see.”

“It’s not that bad.”

“Barry. Let me see it.”

I unwrapped the sock, exposing a long gash that ran from my wrist to my elbow. It had missed the vein by an inch, but ran deeper at the muscle, where pinkish flesh pulsed out from under the skin. Hoping to calm her down, I explained what had happened: A friend and I had hitchhiked out to his family’s farm, and it started to rain, and on the farm was a terrific place to mudslide, and there was this barbed wire that marked the farm’s boundaries, and….

“Lolo!”

My mother laughs at this point when she tells this story, the laughter of a mother forgiving her child those sins that have passed. But her tone alters slightly as she remembers that Lolo suggested we wait until morning to get me stitched up, and that she had to browbeat our only neighbor with a car to drive us to the hospital. She remembers that most of the lights were out at the hospital when we arrived, with no receptionist in sight; she recalls the sound of her frantic footsteps echoing through the hallway until she finally found two young men in boxer shorts playing dominoes in a small room in the back. When she asked them where the doctors were, the men cheerfully replied “We are the doctors” and went on to finish their game before slipping on their trousers and giving me twenty stitches that would leave an ugly scar. And through it all was the pervading sense that her child’s life might slip away when she wasn’t looking, that everyone else around her would be too busy trying to survive to notice—that, when it counted, she would have plenty of sympathy but no one beside her who believed in fighting against a threatening fate.

It was those sorts of issues, I realize now, less tangible than school transcripts or medical services, that became the focus of her lessons with me. “If you want to grow into a human being,” she would say to me, “you’re going to need some values.”

Honesty—Lolo should not have hidden the refrigerator in the storage room when the tax officials came, even if everyone else, including the tax officials, expected such things. Fairness—the parents of wealthier students should not give television sets to the teachers during Ramadan, and their children could take no pride in the higher marks they might have received. Straight talk—if you didn’t like the shirt I bought you for your birthday, you should have just said so instead of keeping it wadded up at the bottom of your closet. Independent judgment—just because the other children tease the poor boy about his haircut doesn’t mean you have to do it too.

It was as if, by traveling halfway around the globe, away from the smugness and hypocrisy that familiarity had disclosed, my mother could give voice to the virtues of her midwestern past and offer them up in distilled form. The problem was that she had few reinforcements; whenever she took me aside for such commentary, I would dutifully nod my assent, but she must have known that many of her ideas seemed rather impractical. Lolo had merely explained the poverty, the corruption, the constant scramble for security; he hadn’t created it. It remained all around me and bred a relentless skepticism. My mother’s confidence in needlepoint virtues depended on a faith I didn’t possess, a faith that she would refuse to describe as religious; that, in fact, her experience told her was sacrilegious: a faith that rational, thoughtful people could shape their own destiny. In a land where fatalism remained a necessary tool for enduring hardship, where ultimate truths were kept separate from day-to-day realities, she was a lonely witness for secular humanism, a soldier for New Deal, Peace Corps, position-paper liberalism.

She had only one ally in all this, and that was the distant authority of my father. Increasingly, she would remind me of his story, how he had grown up poor, in a poor country, in a poor continent; how his life had been hard, as hard as anything that Lolo might have known. He hadn’t cut corners, though, or played all the angles. He was diligent and honest, no matter what it cost him. He had led his life according to principles that demanded a different kind of toughness, principles that promised a higher form of power. I would follow his example, my mother decided. I had no choice. It was in the genes.

“You have me to thank for your eyebrows … your father has these little wispy eyebrows that don’t amount to much. But your brains, your character, you got from him.”

Her message came to embrace black people generally. She would come home with books on the civil rights movement, the recordings of Mahalia Jackson, the speeches of Dr. King. When she told me stories of schoolchildren in the South who were forced to read books handed down from wealthier white schools but who went on to become doctors and lawyers and scientists, I felt chastened by my reluctance to wake up and study in the mornings. If I told her about the goose-stepping demonstrations my Indonesian Boy Scout troop performed in front of the president, she might mention a different kind of march, a march of children no older than me, a march for freedom. Every black man was Thurgood Marshall or Sidney Poitier; every black woman Fannie Lou Hamer or Lena Horne. To be black was to be the beneficiary of a great inheritance, a special destiny, glorious burdens that only we were strong enough to bear.

Burdens we were to carry with style. More than once, my mother would point out: “Harry Belafonte is the best-looking man on the planet.”

It was in this context that I came across the picture in Life magazine of the black man who had tried to peel off his skin. I imagine other black children, then and now, undergoing similar moments of revelation. Perhaps it comes sooner for most—the parent’s warning not to cross the boundaries of a particular neighborhood, or the frustration of not having hair like Barbie no matter how long you tease and comb, or the tale of a father’s or grandfather’s humiliation at the hands of an employer or a cop, overheard while you’re supposed to be asleep. Maybe it’s easier for a child to receive the bad news in small doses, allowing for a system of defenses to build up—although I suspect I was one of the luckier ones, having been given a stretch of childhood free from self-doubt.

I know that seeing that article was violent for me, an ambush attack. My mother had warned me about bigots—they were ignorant, uneducated people one should avoid. If I could not yet consider my own mortality, Lolo had helped me understand the potential of disease to cripple, of accidents to maim, of fortunes to decline. I could correctly identify common greed or cruelty in others, and sometimes even in myself. But that one photograph had told me something else: that there was a hidden enemy out there, one that could reach me without anyone’s knowledge, not even my own. When I got home that night from the embassy library, I went into the bathroom and stood in front of the mirror with all my senses and limbs seemingly intact, looking as I had always looked, and wondered if something was wrong with me. The alternative seemed no less frightening—that the adults around me lived in the midst of madness.

The initial flush of anxiety would pass, and I would spend my remaining year in Indonesia much as I had before. I retained a confidence that was not always justified and an irrepressible talent for mischief. But my vision had been permanently altered. On the imported television shows that had started running in the evenings, I began to notice that Cosby never got the girl on I Spy, that the black man on Mission Impossible spent all his time underground. I noticed that there was nobody like me in the Sears, Roebuck Christmas catalog that Toot and Gramps sent us, and that Santa was a white man.

I kept these observations to myself, deciding that either my mother didn’t see them or she was trying to protect me and that I shouldn’t expose her efforts as having failed. I still trusted my mother’s love—but I now faced the prospect that her account of the world, and my father’s place in it, was somehow incomplete.