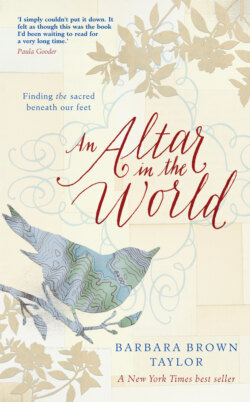

Читать книгу An Altar in the World - Barbara Brown Taylor - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1. The Practice of Waking Up to God

VISION

The day of my spiritual awakening was the day I saw—and knew I saw—all things in God and God in all things.

—Mechtild of Magdeburg

Many years ago now I went for a long walk on the big island of Hawaii, using an old trail that runs along the lava cliffs at the edge of the sea. More than once the waves drenched me, slamming into the cliffs and shooting twenty feet into the air. More than once I saw double rainbows in the drops that fell back into the sea. The island had already won my heart. Part of it was the sheer gorgeousness of the place, but the ground also felt different under my feet. I was aware of how young it was: the newest earth on the face of the earth, with a nearby volcano still making new earth even as I walked. In my experience, every place has its own spirit, its own character and depth. If I had grown up in the Arizona desert, I would be a different person than the one who grew up in a leafy suburb of Atlanta. If I lived by the ocean even now, my senses would be tuned to an entirely different key than the one I use in the foothills of the Appalachians.

On the big island of Hawaii, I could feel the adolescent energy of the lava rock under my feet. The spirit of that land was ebullient, unrefined, entirely pleased with itself. Its divinity had not yet suffered from the imposition of shopping malls, beach homes, or luxury hotels. I caught its youthfulness and walked farther that day than I thought I could, ending up at a small tidal pool on the far southwestern tip of the island.

After the crashing of the waves, the sanctuary of the still pool hit me with the sound of sheer silence. The calm water lay so green and cool before me that it calmed me too. Nothing stirred the face of the water save the breeze coming off the ocean, which caused it to wrinkle from time to time. Walking around the pool, I came to three stones set upright near the edge where the water was deepest. All three were shaped like fat baguettes, with the tallest one in the middle. The other two were set snug up against it, the same grey color as humpbacked whales. All together, they announced that something significant had happened in that place. I was not the first person to be affected by it. Whoever had come before me had set up an altar, and though I might never know what that person had encountered there, I knew the name of the place: Bethel, House of God.

At least that is what Jacob called the place where he encountered God—not on a gorgeous island but in a rocky wilderness—where he saw something that changed his life forever. The first time I read Jacob’s story in the Bible, I knew it was true whether it ever happened or not. There he was, still a young man, running away from home because his whole screwy family had finally imploded. His father was dying. He and his twin brother, Esau, had both wanted their father’s blessing. Jacob’s mother had colluded with him to get it, and though his scheme worked, it enraged his brother to the point that Jacob fled for his life. He and his brother were not identical twins. Esau could have squashed him like a bug. So Jacob left with little more than the clothes on his back, and when he had walked as far as he could, he looked around for a stone he could use for a pillow.

When he had found one the right size, Jacob lay down to sleep, turning his cheek against the stone that was still warm from the sun. Maybe the dream was in the stone, or maybe it fell out of the sky. Wherever the dream came from, it was vivid: a ladder set up on the earth, with the top of it reaching to heaven and the angels of God ascending and descending it like bright-winged ants. Then, all of a sudden, God was there beside Jacob, without a single trumpet for warning, promising him safety, children, land. “Remember, I am with you,” God said to him. “I will not leave you until I have done what I have promised you.”

Jacob woke while God’s breath was still stirring the air, although he saw nothing out of the ordinary around him: same wilderness, same rocks, same sand. If someone had held a mirror in front of his face, Jacob would not have seen anything different there either, except for the circles of surprise in his eyes. “Surely the Lord is in this place,” he said out loud, “—and I did not know it!” Shaken by what he had seen, he could not seem to stop talking. “How awesome is this place!” he went on. “This is none other than the house of God, and this is the gate of heaven.”1

It was one of those dreams he could not have made up. It was one of those dreams that is so much more real than what ordinarily passes for real that trying to figure out “what really happened” involves a complete re-definition of terms. What is really real? How do you know? Can you prove it? Even if Jacob could never find the exact place where the feet of that heavenly ladder came to earth—even if he could never find a single angel footprint in the sand—his life was changed for good. Having woken up to God, he would never be able to go to sleep again, at least not to the divine presence that had promised to be with him whether he could see it or not. What really happened? God knows. All Jacob knew was that he had to mark the spot.

Looking around for something that would do the trick, he spotted the obvious choice: his stone pillow, lying right where he had left it, although the sand around it was churned up from his unusual night’s sleep. First he dug a sturdy footing for the stone. Then he stood it up, ladderlike, and set it into place. Then he poured oil on it and gave it a name: Bethel, House of God. Looking back at it as he walked away, he saw a stone finger rooted in the earth, pointing straight up through the sky.

Sitting in my salty, fragrant church back on the big island of Hawaii, I looked at the three stones pointing straight up through the sky and wondered how I had forgotten that the whole world is the House of God. Who had persuaded me that God preferred four walls and a roof to wide-open spaces? When had I made the subtle switch myself, becoming convinced that church bodies and buildings were the safest and most reliable places to encounter the living God?

I had loved plenty of churches in my life by then, beginning with a little white frame chapel in the Ohio countryside with apple trees in the churchyard. The pastor there was the first adult who looked me in the eyes and listened to what I said. He was the first to tuck God’s pillow under my head. Later I loved a downtown Atlanta church where rows of Tiffany windows turned all the people inside faintly blue. With these people I learned how hard it was to do something as simple as loving our urban neighbors a fraction as much as we loved our true-blue selves. I loved the Washington National Cathedral, where presidents were laid to rest, pilgrims walked labyrinths, and rock doves occasionally roosted in the rafters. I loved tiny Grace-Calvary Episcopal Church in Clarkesville, Georgia, where for five and a half years I watched the wind bend the white pines from side to side through wavy clear glass windows while I celebrated communion with the faithful inside.

I encountered God in all of those places, which may explain why I began to spend more time in churches than I did in the wide, wide world. The physical boundaries of those houses were clear. The communities in them were identified. Here is the church; here is the steeple; open the doors and see all the people. I more or less knew what my job was inside those doors, and the rewards of doing it were clear. Engaging in ancient rituals with people as ordinary as I was, I watched their faces open to reveal night skies full of stars. Who would ever have imagined they carried so much around within them? Turning aside from everything else we could have been doing, we did things together in those sacred spaces that we did nowhere else in our lives: we named babies, we buried the dead, we sang psalms, we praised God for our lives. When we did, it was as if we were building a fire together, each of us adding something to the blaze so that the light and heat in our midst grew. Yet the light exceeded our fire, just as the warmth did. We did our parts, and then there was more. There was More.

Still, some of us were not satisfied with our weekly or biweekly encounters with God. We wanted more than set worship services or church work could offer us. We wanted more than planning scavenger hunts for the youth group, more than polishing silver with the altar guild, more than serving on the outreach committee or rehearsing anthems with the choir. We wanted More. We wanted a deeper sense of purpose. We wanted a stronger sense of God’s presence. We wanted more reliable ways both to seek and to stay in that presence—not for an hour on Sunday morning or Wednesday afternoon but for as much time as we could stand.

And yet the only way most of us knew to get that was to spend more time in church. So we volunteered more, dreamed up more programs, invited more people to more classes where we could read more books. The minute we walked back out to our cars, many of us could feel the same old gnawing inside. Once we left church, we were not sure what to do anymore. We knew some things we could do to feel close to God inside the church, but after we stepped into the parking lot we lost that intimacy. The boundaries were not so clear out there. Community was not so easy to find. Without Tiffany windows tinting them blue, people looked pretty much the same. From the parking lot, they looked as ordinary as everything else. The only More out there was more of the same.

That, at least, is how it looked to those of us who had forgotten that the whole world is the House of God. Somewhere along the line we bought—or were sold—the idea that God is chiefly interested in religion. We believed that God’s home was the church, that God’s people knew who they were, and that the world was a barren place full of lost souls in need of all the help they could get. Plenty of us seized on those ideas because they offered us meaning. Believing them gave us purpose and worth. They gave us something noble to do in the midst of lives that might otherwise be invisible. Plus, there really are large swaths of the world filled with people in deep need of saving.

The problem is, many of the people in need of saving are in churches, and at least part of what they need saving from is the idea that God sees the world the same way they do. What if the gravel of a parking lot looks as promising to God as the floorboards of a church? What if a lost soul strikes God as more reachable than a lifelong believer? What if God can drop a ladder absolutely anywhere, with no regard for the religious standards developed by those who have made it their business to know the way to God?

I could not possibly say.

Although I have spent a lot of my life in jobs that require me to speak for God, I am still reluctant to do it for all kinds of reasons. In the first place, I have discovered that people who want to speak to me about God generally have an agenda. However well-intentioned they may be, their speech tends to serve as a means to their own ends. They have a clear idea about how I should respond to what they are saying. They have a clear destination in mind for me, and nine times out of ten it is not some place I want to go.

In the second place, too much speech about God strikes me as disrespectful. In the Upanishads, God is described as “Thou Before Whom All Words Recoil.” This sounds right to me. Anything I say about God will be inadequate. No matter how hard I try to say something true about God, the reality of God will eclipse my best words. The only reality I can describe with any accuracy is my own limited experience of what I think may be God: the More, the Really Real, the Luminous Web That Holds Everything in Place.

Even then, there is a good chance that my words will serve as an impediment for those who hear them. If “the Really Real” makes no sense to you, then you will have to find some way around that phrase before you can get on with your own description, which means that my speech about God has just done more to block your way than to open it. The only reason to accept such a risk is because most of us need to hear what other people say before we decide what to say about those same things ourselves. With a modicum of generosity, we can all pitch what we have on the fire and watch for the More to flame up. In the morning, when we wake up around a circle of glowing coals with warm stone pillows under our heads, there is always a chance that one of us will sit up and say, “Surely the Lord is present in this place, and I did not know it!”

When those words came out of Jacob’s mouth, there was no temple in Jerusalem. Without one designated place to make their offerings, people were free to see the whole world as an altar. The divine could erupt anywhere, and when it did they marked the spot in any way they could, although there was no sense hanging around for long, since God stayed on the move. For years and years, the Divine Presence was content with a tent—a “tent of meeting,” the Bible calls it—which was not where God lived full-time but where God camped out with people who were also on the move. God met them outside the tent, too, but the tent was the face-to-face place, the place where the presence of God was so intense that Moses was the only person who could stand it. When Moses came out of the tent of meeting, his face was so bright that he wore a veil over it in order not to scare the children.

The tent suited God just fine for hundreds of years. It suited God so well, in fact, that when King David proposed giving God a permanent address, God balked. “Are you the one to build me a house to live in?” God asked. “I have not lived in a house since the day I brought up the people of Israel from Egypt to this day, but I have been moving about in a tent and a tabernacle.”2 So David did not build God a temple. His son Solomon did, however, and from that day forth God’s address was Mount Zion, Jerusalem. Even today, two ruined temples later, people from around the world still go to Mount Zion to tuck their prayers into the foundation stones of God’s old house.

As important as it is to mark the places where we meet God, I worry about what happens when we build a house for God. I am speaking no longer of the temple in Jerusalem but of the house of worship on the corner, where people of faith meet to say their prayers, because saying them together reminds them of who they are better than saying them alone. This is good, and all good things cast shadows. Do we build God a house so that we can choose when to go see God? Do we build God a house in lieu of having God stay at ours? Plus, what happens to the rest of the world when we build four walls—even four gorgeous walls—cap them with a steepled roof, and designate that the House of God? What happens to the riverbanks, the mountaintops, the deserts, and the trees? What happens to the people who never show up in our houses of God?

The people of God are not the only creatures capable of praising God, after all. There are also wolves and seals. There are also wild geese and humpback whales. According to the Bible, even trees can clap their hands. Francis of Assisi loved singing hymns with his brothers and sisters—who included not only Brother Bernard and Sister Clare, but also Brother Sun and Sister Moon. Francis could not have told you the difference between “the sacred” and “the secular” if you had twisted his arm behind his back. He read the world as reverently as he read the Bible. For him, a leper was as kissable as a bishop’s ring, a single bird as much a messenger of God as a cloud full of angels. Francis had no discretion. He did not know where to draw the line between the church and the world. For this reason among others, Francis is remembered as a saint.

Of course, Francis also built a church. In a vision he had, as vivid as Jacob’s vision of the divine ladder, God called upon Francis to rebuild the church. Unsure what church God meant, Francis chose a ruined one near where he lived. He recruited all kinds of people to help him build it. Some of them just came to watch, and before they knew it were mixing cement. Others could not lift a single brick without help, but that worked out, since it led them to meet more people than they might have if they had been stronger. To most of them, building the church became more important than finishing it. Building it together gave people who were formerly invisible to each other meaning, purpose, and worth. When it was done at last, Francis’s church did not stand as a shelter from the world; it stood as a reminder that the whole world was God’s House.

I knew that when I was young, and then I forgot.

My first church was a field of broom grass behind my family’s house in Kansas, where I spent days in self-forgetfulness. A small stream held swimmers, wigglers, skaters, and floaters, along with bumps of unseen things moving under the mud. When I blurred my eyes, the sun sparkling on the moving surface turned into a living quilt of light. Later, I found a magnolia tree in Georgia that offered high, medium, or low perches, depending on how far I could climb. My fear of falling made the ascent more vivid. When I had finally settled on a branch, my arms trembling from the haul, leaning back against the trunk felt as safe as leaning against my father. The huge white flowers leaked a scent much slighter than their size. When I bent to touch one, the cool, heavy petals fell to the ground like swooning birds.

Of course, I did other things as well. I went to school. I helped my mother with the dishes. I looked after my younger sisters. I worked in the yard with my father. As I grew, I also smoked cigarettes with my friends, kissed boys in the backs of buses, and suffered the cruelties of the high school caste system. I became too tall too fast. My pale skin would not tan. I had no need of a brassiere until I was almost sixteen, by which time all the other girls seemed to have graduated from a course in voluptuousness that I did not have the resources to attend.

Fortunately, I had home remedies for the self-loathing that overtook me on a regular basis. After school I headed straight to the stables, where I kept a strawberry roan gelding named Frosty. He was always glad to see me. Although riding him was the point, I was just as happy to clean his stall. When I was through, he would stand very still as I lay my cheek against his, until the sweet hay smell of his breath revived me. In the evenings, I did my homework, wishing for more time with Melville’s Moby-Dick and less with Euclid’s geometry.

When I was sixteen, I joined a real church under my own steam. I was not then aware of the vast differences among churches. I thought God was God, and according to some of my friends I did not know the first thing about who He was or what He wanted from me. So I joined their church to find out, and quickly learned that my love of the world was misplaced. The church taught me that only God was worthy of my love, and that only the Bible could teach me about God. For the first time in my life, I was asked to choose between God and the world.

Like all who write what they remember, I am inventing the truth. But what I think I remember is that I learned in church to fear the world, or at least to suspect it. I learned that my body was of the world and that my bodily shame was appropriate. The kissing of boys should stop at once, my new teachers told me, as should all other flirtations with the temptations of the flesh. In the same way that the church was holier than the world, so was the spirit holier than the flesh. God so loved the world that He gave His only Son, but if the world had not been such a rotten place then that Son need not have died.

From many of those same churches I learned how important it was to love God and my neighbor as myself, to share what I had with those who had less, and to stand ready to lay down my life for my friends. I rose to those teachings like a seedling to the sun. They tapped my secret wish to become gallant. They gave me important things to do. If they also drove a wedge between me and the world I so loved, then I do not remember noticing that at the time. What I noticed was that I had found a church, a holy book, and a people of the book who promised me safety from worldly powers I did not even know were there. All I had to do was trust the God of the church more than I trusted the gods of the world, living the kind of in-but-not-of-the-world life that announced where my true allegiance lay.

From that rough start, I went on to learn that there are many different kinds of churches, many different ways to read the Bible, and many different ways that people of faith engage the world. Yet I never entirely escaped the subtle teaching that the world of the flesh is not to be trusted. As lovely, startling, or disturbing as that world may be, it is a world of appearances, not of truth—or so I was taught. Only the Bible contains the real truth, the truth that sets people free.

Fortunately, the Bible I set out to learn and love rewarded me with another way of approaching God, a way that trusts the union of spirit and flesh as much as it trusts the world to be a place of encounter with God. Like anyone else, I do some picking and choosing when I go to my holy book for proof that the world is holy too, but the evidence is there. People encounter God under shady oak trees, on riverbanks, at the tops of mountains, and in long stretches of barren wilderness. God shows up in whirlwinds, starry skies, burning bushes, and perfect strangers. When people want to know more about God, the son of God tells them to pay attention to the lilies of the field and the birds of the air, to women kneading bread and workers lining up for their pay.

Whoever wrote this stuff believed that people could learn as much about the ways of God from paying attention to the world as they could from paying attention to scripture. What is true is what happens, even if what happens is not always right. People can learn as much about the ways of God from business deals gone bad or sparrows falling to the ground as they can from reciting the books of the Bible in order. They can learn as much from a love affair or a wildflower as they can from knowing the Ten Commandments by heart.

This is wonderful news. I do not have to choose between the Sermon on the Mount and the magnolia trees. God can come to me by a still pool on the big island of Hawaii as well as at the altar of the Washington National Cathedral. The House of God stretches from one corner of the universe to the other. Sea monsters and ostriches live in it, along with people who pray in languages I do not speak, whose names I will never know.

I am not in charge of this House, and never will be. I have no say about who is in and who is out. I do not get to make the rules. Like Job, I was nowhere when God laid the foundations of the earth. I cannot bind the chains of the Pleiades or loose the cords of Orion. I do not even know when the mountain goats give birth, much less the ordinances of the heavens. I am a guest here, charged with serving other guests—even those who present themselves as my enemies. I am allowed to resist them, but as long as I trust in one God who made us all, I cannot act as if they are no kin to me. There is only one House. Human beings will either learn to live in it together or we will not survive to hear its sigh of relief when our numbered days are done.

In biblical terms, it is wisdom we need to live together in this world. Wisdom is not gained by knowing what is right. Wisdom is gained by practicing what is right, and noticing what happens when that practice succeeds and when it fails. Wise people do not have to be certain what they believe before they act. They are free to act, trusting that the practice itself will teach them what they need to know. If you are not sure what to think about washing feet, for instance, then the best way to find out is to practice washing a pair or two. If you are not sure what to believe about your neighbor’s faith, then the best way to find out is to practice eating supper together. Reason can only work with the experience available to it. Wisdom atrophies if it is not walked on a regular basis.

Such wisdom is far more than information. To gain it, you need more than a brain. You need a body that gets hungry, feels pain, thrills to pleasure, craves rest. This is your physical pass into the accumulated insight of all who have preceded you on this earth. To gain wisdom, you need flesh and blood, because wisdom involves bodies—and not just human bodies, but bird bodies, tree bodies, water bodies, and celestial bodies. According to the Talmud, every blade of grass has its own angel bending over it, whispering, “Grow, grow.”

How does one learn to see and hear such angels?

If there is a switch to flip, I have never found it. As with Jacob, most of my visions of the divine have happened while I was busy doing something else. I did nothing to make them happen. They happened to me the same way a thunderstorm happens to me, or a bad cold, or the sudden awareness that I am desperately in love. I play no apparent part in their genesis. My only part is to decide how I will respond, since there is plenty I can do to make them go away, namely: 1) I can figure that I have had too much caffeine again; 2) I can remind myself that visions are not true in the same way that taxes and the evening news are true; or 3) I can return my attention to everything I need to get done today. These are only a few of the things I can do to talk myself out of living in the House of God.

Or I can set a little altar, in the world or in my heart. I can stop what I am doing long enough to see where I am, who I am there with, and how awesome the place is. I can flag one more gate to heaven—one more patch of ordinary earth with ladder marks on it—where the divine traffic is heavy when I notice it and even when I do not. I can see it for once, instead of walking right past it, maybe even setting a stone or saying a blessing before I move on to wherever I am due next.

Human beings may separate things into as many piles as we wish—separating spirit from flesh, sacred from secular, church from world. But we should not be surprised when God does not recognize the distinctions we make between the two. Earth is so thick with divine possibility that it is a wonder we can walk anywhere without cracking our shins on altars. Jacob’s nowhere, about which he knew nothing, turned out to be the House of God. Even though his family had imploded, even though he had made his brother angry enough to kill him, even though he was a scoundrel from the word go—God decided to visit Jacob right where he was, though Jacob had not been right about anything so far and never would be. God gave Jacob vision, so Jacob could see the angels going up and down from earth to heaven, going about their business in the one and only world there is.

The vision showed Jacob something he did not know. He slept in the House of God. He woke at the gate of heaven. None of this was his doing. The only thing he did right was to see where he was and say so. Then he turned his pillow into an altar before he set off, praising the God who had come to him where he was.

Notes

1 Genesis 28:16 –17.

2 2 Samuel 7:5– 6.