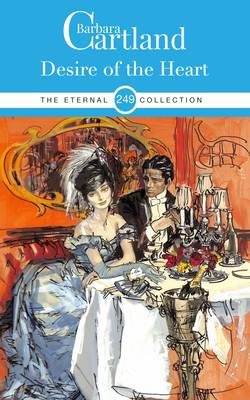

Читать книгу Desire of the Heart - Barbara Cartland - Страница 3

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER THREE

ОглавлениеThe King and Queen entered the ballroom and the ladies curtseying on either side of them seemed to rise and fall like the wave of some gloriously-shaded sea.

‘He is exactly like his pictures,’ Cornelia thought as she watched, ‘but the Queen is far, far lovelier.’

Queen Alexandra, in a dress of grey satin, managed to make every other woman seem clumsy and dowdy. The perfect oval of her face, the fine brow, clear-cut nose and dazzling complexion were enhanced by the colour of her eyes. Her little head, set upon a firm white throat, had a grace and that was inimitable and the radiance of her smile made everyone she looked at her captive.

The ballroom at Londonderry House, with its lovely glittering chandeliers, its white and gold decoration, its fabulous portraits and banks of hothouse flowers, was a sight to make anyone as unsophisticated as Cornelia gasp in astonishment

And the guests were even more awe-inspiring. The glitter of tiaras on the heads of the ladies, their sparkling necklaces and matching corsages of diamonds, emeralds and sapphires were almost blinding. Their dresses made Cornelia realise how little she knew about fashion and how ridiculous she must have looked on her arrival in London.

She was by no means that satisfied with her appearance now, even though her gown had come from Bond Street and her hair had been arranged by Aunt Lily’s hairdresser. There had not been time for her to have anything made especially for her and the only dress that could be altered to fit her at short notice was of white satin and trimmed with Venetian lace.

The price of this gown had left Cornelia speechless and yet, when she had put it on, she knew that it was not really becoming to her.

She had regarded herself in the mirror before she left her bedroom and exclaimed,

“Goodness, but I look a fright!”

“Oh, no! miss, you look charmin’. Just as a young girl should look,” the maid who was helping her dress reassured her, but Cornelia made a grimace at her own reflection.

“Flattery does not hide holes in one’s stockings,” she said and laughed at the expression on the maid’s face.”

“That is an Irish saying,” she explained. “It was one of Jimmy’s favourites. He was my father’s groom and nobody could flatter him into believing anything but the truth. Let’s be frank and admit that I look terrible.”

“It’s just because you’re not used to bein’ dressed up, miss. You will feel all right when you are among the other ladies.”

Cornelia said nothing. She was inspecting her hair, looking with something like dismay at the monumental edifice that Monsieur Henri had erected at the top of her head. Frizzed, waved and arranged over a false frame, the effect was to make her face seem very small and lost beneath a gigantic bird’s nest.

It was most uncomfortable and in spite of Monsieur Henri’s ministrations Cornelia was sure that long before she reached the ball wisps would descend at the back of her neck or a curl or two become detached from the top.

There was, however, nothing she could do about it now except to yearn with a sudden passionate nostalgia for Rosaril.

All day long she had thought about the low grey house surrounded by its green fields, the mountains purple against the sky and the sea shimmering in the distance. She thought, too of the horses waiting for her in the paddocks, wondering why she had forgotten them, of Jimmy whistling in the stables, perhaps longing for her as she was longing for him and not once but a dozen times she had to bite her lip to prevent her tears from overflowing.

Sometimes in seeing so many new things and of watching a new world that was at times unexpectedly beautiful, she would forget Rosaril for a little while, but always when she least expected it, the ache for Ireland would come flooding over her with an insistence that would not be denied.

Then in a blind misery she would hate everything that was unfamiliar and would pine only for the place and the people she loved. She clung to her spectacles as a drowning man might cling to a lifebuoy. They were her only protection against the curiosity of the strangers surrounding her.

Her uncle and aunt’s house seemed to be filled with people from dawn to eve. There were guests to luncheon, to tea and to dinner. People came to call or dropped in in the hope of finding Lady Bedlington at home and, when they were introduced to her, Cornelia would see the quick look of speculation in their eyes and hear the curiosity in their voices.

She was shrewd enough to realise that the story of her unexpected fortune preceded her wherever she went, but she also guessed that there was something strange and unusual about her aunt being in the position of a chaperone.

“It must seem as if you had a daughter of your own, Lily dear,” one woman remarked with a sweetness that did not hide the sting lying beneath the surface.

“Don’t you mean a sister, dearest?” Lily had retorted, but not before Cornelia had seen the flash of anger in her aunt’s eyes and knew that the question had wounded her vanity.

Cornelia had been but a few hours in the house before she guessed that her aunt was by no means pleased at her arrival. It was not anything that Lily put into words, it was just a coolness in her manner, a sudden sharpness in her voice and the impression Cornelia had of being a nuisance. There was also an undercurrent between husband and wife that did not go unnoticed.

They were obviously on edge with each other and it made Cornelia even more shy and uncomfortable than she was already.,

‘I hate them and they are bored with me,’ she said to herself the first night ‘Why, why must I stay?’

She had argued this point too long with Mr. Musgrave, the Solicitor, to hope that there was any chance of her being allowed to return to Rosaril. She knew the answer only too well ‘young ladies do not live alone without a chaperone, young ladies who were orphaned have as a Guardian their next of kin, young ladies must take their place in Society, young ladies, young ladies!’

How Cornelia loathed those expressions! She did not want to be a young lady, she only wanted to be a child again, a child at Rosaril, riding the horses, running with the dogs and coming back to the house to laugh and joke with Papa and Mama until it was time for bed.

How happy they had been, how perfectly completely happy until that terrible accident. Even now Cornelia shied away from the memory of it. It was something dark and terrible in her life. Dearest, green and lovely Rosaril, she could think of nothing else and yet Papa had spoken so often of the gaieties and excitements of London.

“I really want to see the lights of Piccadilly Circus again,” he would say with a yearning note in his voice. “I want to stroll into The Empire and listen to the show and I want to go to Romano’s, have supper with a Gaiety Girl, and then, if I am feeling respectable, I will put in an appearance at one of the balls and see how lovely the ladies are looking.”

“Tell us about it, tell us just who you would meet, Papa,” Cornelia would beg and her mother would lean back in the-chair, smiling while they listened to his reminiscences of the London Season and the gaieties that could be enjoyed by a popular young man-about-town.

‘This is the sort of ball Papa went to,’ Cornelia thought suddenly and awoke to the fact that Lily was stepping forward to curtsey to the King.

With a feeling of stupefaction she heard Lily speak her own name and then she too was curtseying a little awkwardly, her knees suddenly weak and. trembling.

“So you have only just arrived from Ireland,” the King said kindly in his thick guttural voice, but with the charm that had gained him the friendship of all Europe. “I remember your father and I was sorry to hear of the accident that ended his life.”

“Thank you, sir,” Cornelia managed to stammer before, with a smile of approval at Lily, His Majesty passed on.

The orchestra was playing a waltz and, as Lily and Cornelia moved back a little to leave the room for the dancers, Cornelia saw a tall man wending his way towards them through the gyrating couples.

She recognised him instantly. He was the man she had seen in the phaeton as she and her uncle were driving down Upper Grosvenor Street. Strangely enough she had thought of him many times since that moment when she had watched him master his horses and heard her uncle swear at the sight of him.

Why he should remain in her mind she had no idea and yet now, as he came towards them, she had a strange sensation of inevitability.

She was aware that her aunt was turning her head as if in search of someone and she wondered if she was looking for Uncle George whom she could see far away at the end of the ballroom talking with two elderly men.

The dark young man had reached their side.

“Drogo.” Lily spoke his name softly.

“Will you dance with me?”

“No, of course not!”

Cornelia wondered why she should refuse his invitation and, as she looked and listened, standing a little in the background, Lily turned towards her,

“This is Cornelia or perhaps I should be formal and introduce you properly. Cornelia let me present the Duke of Roehampton – Miss Cornelia Bedlington.”

There was something mocking in her aunt’s voice, something else that Cornelia did not understand. She held out her hand and the Duke took it for a brief instant in his.

“You may dance with Cornelia,” Lily said.

And it was an order.

“Will you dance with me later?” the Duke asked her.

“No,” Lily replied.

They looked for a moment into each other’s eyes. For a second they were both very still, until with an effort Lily turned away, opening her fan and fanning her face as if she suddenly felt stifled.

“May I have this dance?”

The Duke was bowing to Cornelia.

She inclined her head and he put his arm round her waist and then swung her out onto the floor. He danced well and Cornelia was thankful that she was light and that she knew what to do. Those times that she had danced with Papa in the drawing room at Rosaril, while Mamma played the piano, were a necessity now.

“I hate women who dance badly,” Papa had said impatiently when she had been unable to follow his steps.

It was more difficult to dance in a crowded ballroom than on a strip of parquet by a bow window, but it was much more exciting.

Cornelia glanced up at the Duke through her spectacles. There was something aloof and detached in his expression as if his thoughts were far away.

And then, as she looked at him, as she realised how close they were together and felt his hand clasping hers through the thin kid of her white glove, her heart seemed to beat more quickly and she felt a sudden strange sensation in her throat

For a moment she thought that she must be giddy and yet her head felt clear enough and there was a lightness and exhilaration in her body such as she had never known before.

How good-looking he was, she thought. The way his hair grew back from his forehead was so distinguished and the squareness of his chin made her certain that he was a decisive person. There was also a pride and dignity about him that reminded her of her father.

He too had been proud and, even when he had been gay and irresponsible, his air of good breeding had never been lost or forgotten. The Duke was not gay, Cornelia thought, but she liked his seriousness.

They danced in silence and, when the waltz came to an end, they walked, still without speaking, back to where Lily stood in the centre of a group of people laughing and talking.

“Thank you,” the Duke bowed to Cornelia and then he turned and walked away.

“Did you enjoy your dance, Cornelia?”

There was a smile on Lily’s lips, but it was forced and her blue eyes were hard.

“Yes, thank you.”

“Well, it is not everyone who can say that the first dance they ever danced in London was with the most eligible bachelor in England. You are a very lucky girl,” Lily said tartly.

“He would not have danced with me ‒ if you had not told him to,” Cornelia replied and wondered why it hurt her to say the words.

“Why does your niece wear darkened spectacles?” someone asked.

It was Lady Russell, a petulant beauty with a reputation of speaking her mind, however discomforting, to other people.

“She injured her eyes out hunting,” Lily replied. “Nothing serious, but she tells me that she has been ordered to keep them on for the next few months. So tiresome for the poor child. But then I always did think that hunting was a dangerous sport.”

“That is only because you don’t hunt yourself, Lily, not foxes at any rate.”

There was a little scream of laughter, but Lily seemed unperturbed. She drew Cornelia away and introduced her to some women who, seated in chairs round the ballroom, watched the dancers with critical and usually censorious eyes.

Lily was looking magnificent this evening in a gown of pale blue chiffon that swirled out around her feet in copious flounces and matched by a tiara and necklace of turquoises set with diamonds.

There was no one in the ballroom so lovely, Cornelia felt, and was not surprised that, as every dance began, young men hurried to invite her aunt to take the floor with them. It was with ill grace that they found themselves forced to dance with Cornelia instead and, like her first dance with the Duke, they invariably danced in silence as Cornelia had nothing to say.

She noticed, as she moved around the floor, that the Duke had disappeared. He danced with no one else. She caught a glimpse of him once talking to Aunt Lily. They appeared to argue and there was little doubt from the expression on the Duke’s face that he was annoyed.

Yet, to Cornelia’s surprise, a little later, when she was not dancing, he came to her side and asked her to go down to supper with him.

She looked at her aunt before she answered.

“Yes, of course, go with the Duke, Cornelia.”

“Will you not you come with us?” he enquired.

“The Spanish Ambassador is taking me. Run along and enjoy yourselves, my children.”

She was being deliberately provocative, even Cornelia could see that, but why she could not understand. The Duke held out his arm and they joined the procession of notabilities that was winding its way downstairs to the huge panelled dining room on the ground floor.

They sat together at a small side table, the Duke refusing to take a seat at the bigger one where a number of important people had been placed.

Powdered footmen, wearing a heavy livery ornamented with gold braid, brought them champagne and Cornelia sipped a little from her glass. She had drunk champagne before, but somehow it tasted different here in these rich sparkling surroundings, from how it had done at Rosaril when they drank toasts at Christmas or after one of their horses had won a race.

“Do you like London?”

It was the first conversational question that the Duke had addressed to her.

“No.”

She had not meant to speak so vehemently, but somehow the truth was out before she had time to think.

He looked surprised.

“I thought all women enjoyed the balls and gaieties of the Season.”

“I prefer Ireland,” Cornelia replied.

She felt desperately shy of him. Never before had she sat alone at a table with a man. But that was not the only reason.

There was something about the Duke that made her feel different in herself and in some strange way she felt happy, happier than she had been for a long time.

She could not analyse her feelings, she only knew that it was exciting and breathtaking to sit beside him even while she had nothing to say.

Food was brought to them, course after course of delicious and exotic dishes such as Cornelia had never tasted before. Yet she did not taste them now.

The room was filled with gay chattering people, but she did not hear any of them. She could only watch from behind darkened spectacles the man who was sitting at her side and be acutely conscious of his presence.

“What did you do with yourself in Ireland?”

He was making an effort and somehow she must force herself to answer him.

“We bred and trained horses, racehorses mostly.”

“I have a stud too,” the Duke volunteered. “Unfortunately I have not been at all lucky this year, but I hope to win the Ascot Gold Cup with Sir Galahad.”

“Did you breed him yourself?” Cornelia asked.

“No, I bought him two years ago.”

Cornelia wondered what she could say next. If she had been sitting with an Irishman, there would have been so much to talk about. They could have compared notes on what had won at the races this year and the year before. They could have talked about the jockeys and the way certain horses were badly ridden and that there was a suspicion of foul play when Shamrock came romping up for a close finish last month.

But she knew nothing of English owners and English riders and she knew that someone like the Duke did not train his own horses or even buy them himself, so she sat tongue-tied until supper was finished and they went back to the ball.

There were only a few couples dancing as the majority were still downstairs. Lily too was still sitting at the centre table with the Ambassador. Cornelia looked at the Duke a little helplessly and wondering what they should do.

“Shall we sit down?”

He indicated a gilt chair and, when she had seated herself, he sat down beside her.

“You must try to enjoy England,” he began seriously. “You are going to live here and it would be a mistake to think that only Ireland can make you happy.”

Cornelia looked up at him in surprise. She had not expected him to realise that she was unhappy or indeed that she was longing for her home.

“I shall not live here for ever,” she commented, once again speaking the truth before she had time to think.

“I hope we shall be able to persuade you to change your mind,” the Duke said gravely.

“I doubt it.”

The Duke frowned as if her insistence annoyed him and then, as if he made up his mind to something suddenly, he asked,

“May I call on you tomorrow?”

Cornelia looked at him in surprise.

“I suppose so, but surely you should ask Aunt Lily? I have no idea what her plans are.”

“Perhaps it would be best if you told her of my intention to call on you and see you in the afternoon. About three o’clock, I think.”

He spoke rather harshly as if it was an effort for him to enunciate the words and then, as Cornelia did not answer, he rose to his feet, bowed, and leaving her alone, walked across the ballroom floor and down the stairs.

She stared after him. He was different from anyone she had ever known in her life, yet as she watched him go she knew that she wanted him to stay.

She felt a sudden impulse to run after him, to call him back and to talk to him as she had not been able to talk to him at supper.

Fool that she was, she thought, to sit tongue-tied and inarticulate when she had a chance to say so much. Now that she could think, she chided herself for her ungraciousness and her rudeness in saying that she did not like England. How gauche, how ungrateful he must have thought her, a girl who had done nothing and who had seen nothing, criticising the grandeur of this life that was so much a part of him.

She sat twisting her fingers together, railing at herself for being a fool and yet conscious all the time of some inner excitement that she had not known before. She had danced with him, she had sat with him, this man whom she had first seen through a carriage window and had not been able to forget.

The room was filling up again, people were coming back from supper and now with a sense of relief Cornelia saw her aunt moving towards her. Perhaps it was time to go home. She wanted to be alone, she wanted to think.

“What have you done with Drogo?” Lily asked as she reached Cornelia’s side with the Spanish Ambassador resplendent with decorations walking beside her.

“The Duke went downstairs,” Cornelia replied.

“You are a very naughty girl to have had supper with him tête-à-tête,” Lily admonished her. “I don’t know what people will think of me as a chaperone to allow such a thing. There were places kept for you at the Royal supper table, but you ignored them. We shall have to be careful, Your Excellency, or my husband’s niece will gain a reputation for being fast!”

“If Miss Bedlington does anything wrong, you have only to plead for her and so she will be forgiven instantly,” the Ambassador suggested.

“Your Excellency is always so flattering,” Lily smiled.

There was no further mention of the Duke then, but when they drove home an hour later, Cornelia remembered his message.

“The Duke of Roehampton asked if he might call on me tomorrow afternoon,” she said. “I told him that he should ask you, as I had no idea of your plans, but he said that he would come at three o’clock.”

“Then you must be there to receive him,” Lily said and to Cornelia’s surprise there was something like a note of relief in her aunt’s voice.

“What is all this? What’s all this?” Lord Bedlington asked.

He had appeared to be dozing in the corner of the carriage. Now he sat up and turned to look at his wife. He could see her clearly in the light of the street lamps.

“I told you I would not have Roehampton in the house,” he growled.

“He is coming to see Cornelia, George, not me.”

“Why should he do that? Never set eyes on the girl until tonight.”

“I know, dear, but we can hardly refuse to let him see her if he wants to.”

“If you are up to your old monkey tricks – ” Lord Bedlington began, only to receive an indignant shush from his wife.

“Really, George, not in front of Cornelia!”

There was so much righteous indignation in Lily’s voice that her husband subsided into his corner of the carriage.

Cornelia wondered about it when she was in bed but somehow it was extremely difficult to remember anything except for the feeling of the Duke’s arm on her waist and the firmness of his hand clasping hers.

He wanted her to like England. She could remember that too and, as she fell fast asleep, she was thinking that after all she was glad she had come for she had met him and he was English and a very important part of the England that he wanted her to like.

While Cornelia slept, Lily and George Bedlington were arguing.

He had come into Lily’s bedroom soon after she had gone upstairs and dismissed her maid, who was only too glad of the opportunity to go off to bed.

“What is it, George?” she asked irritably. “I wanted Dobson to brush my hair and it is much too late at night for conversation.”

“I have never known you come home so early from a ball before,” her husband retorted.

“Well, I cannot say that I enjoyed having to stand about with all those old women,” Lily pouted, watching her reflection as she did so and telling herself that she did not look a day over twenty-five. “It is beastly of you, George, and well you know it, to make me chaperone this niece of yours. It is just refined cruelty.”

“That is just what I want to talk to you about,” Lord Bedlington said heavily. “What is all this about Roehampton coming here? I told you I have forbidden him from the house.”

“Really, George, you are being very dense,” Lily said. “You forbade him to see me for quite ridiculous and unjust reasons. Of course if it amuses you to be so jealous and make a fool of yourself, there is nothing I can possibly do to stop you, but I really cannot allow you to jeopardise Cornelia’s chances just because of petty prejudice and some horrible indecent suspicions that you cannot justify in the very slightest!”

“I am not going to argue about that all over again,” George Bedlington said. “I may be a fool in many ways, Lily, but I am not such a damn fool as all that. I have told you what I think about you and young Roehampton and that’s all there is to it.”

“Very well, George, if that is what you feel about it there is nothing more to be said, but where Cornelia is concerned it is a different story.”

“What is happening that is just what I want to know? Cornelia does not know this young jackanapes, so why should he come and call on her.”

“Now, George, really, for an intelligent man you are being dense. Don’t you understand that with Cornelia’s fortune she can easily take her pick of the eligible young gentlemen in London?”

“Who says so?” George Bedlington asked.

“I say so,” Lily replied, “and you know I am right. Her fortune is there, isn’t it?”

“Of course it is there. I don’t have all the facts and figures as yet but she is worth three-quarters of a million if she’s worth a penny.”

Then, don’t you see, George,” Lily replied in the voice of one speaking to a backward child, “that with a fortune like that she can take her choice?”

“You don’t mean Roehampton is after her money?” he asked indignantly.

“And why not? You know Emily is always complaining about how hard up they are and what is wrong, I should like to know, with having a niece who is a Duchess? For Heaven’s sake, George, leave things to me and don’t try to interfere.”

“Well, it all seems damned peculiar to me,” he said, scratching his greying hair. “One moment Roehampton’s after you, getting you talked about and trying to make a cuckold of me and the next minute you tell me he is trying to marry my niece? Are there not any other women in the world except those who belong to me?”

“Now, George, don’t worry your head about all this.”

Lily rose from the table as she spoke. With her golden hair streaming over her shoulders and the full curved grace of her figure showing through her thin wrapper, she walked across the room to her husband.

“Don’t be cross and don’t be difficult, George,” she coaxed, putting up her hand to pat his cheek with a gesture that was peculiarly her own.

For a moment he glared at her, remembering his anger a few days earlier when he found out that she had been lying and then her beauty weakened him as it had done so often before.

“All right, have it your own way then, although God knows what you are up to now.”

“Dear George,” Lily kissed his cheek lightly and walked away from him. “I must go to bed, I am dead tired and there is a ball and Reception at the French Embassy tomorrow.”

For a moment George Bedlington hesitated. He looked at the big double bed set in an alcove at the end of the room. The pink-shaded lights shining on either side of it illuminated Lily’s lace-edged pillow with its embroidered and coroneted monogram.

As if she sensed his hesitation and his silence, Lily turned. She had undone the sash of her white wrapper, but now she pulled it closely round her again.

“I am tired, George,” she repeated plaintively.

“All right, goodnight, my dear.”

George walked across the bedroom and closed the door behind him.

When he was gone, Lily stood where he had left her, still clutching the wrapper closely around her body.

Then slowly she let it slip from her shoulders and fall to the floor. With a little cry she flung herself face downwards onto the bed, her face buried in the coroneted pillow.

The self-control she had exercised all the evening broke and now, with a wild anguish that could not be repressed, she cried out his name over and over again,

“Drogo! Drogo! Drogo!”