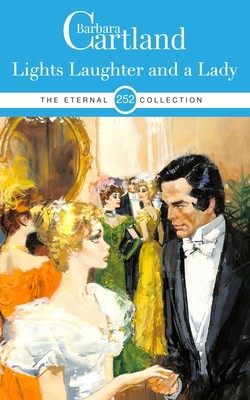

Читать книгу Lights, Laughter and a Lady - Barbara Cartland - Страница 2

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Chapter One ~ 1898

Оглавление“Have you paid off all the debts, Mr. Mercer?” the Honourable Minella Clinton-Wood asked. The elderly man sitting opposite her hesitated before he replied,

“The house, the furniture, the horse and, of course, the estate, which has been sold off bit by bit, have covered practically all of them, Miss Minella.”

“How much is left?”

“Approximately,” answered Mr. Mercer, of Mercer, Conway and Mercer, “one hundred and fifty pounds.”

Minella drew in her breath and, when she did not speak, he continued,

“I have taken it upon myself to keep aside one hundred pounds for you.”

“Should you do that?”

“It is what I insist on doing. After all you cannot live on air and I know you have not yet decided on which of your relations you would prefer to live with.”

The expression on Minella s face was very revealing as she responded,

“As you are aware, Mr. Mercer, that is very difficult. Papa did not have many relatives, and Mama’s are all in Ireland and I have not met any of them.”

“I thought,” Mr. Mercer said quietly, “that you would live with your aunt, Lady Banton, in Bath.”

Minella sighed deeply.

“I suppose that is eventually just what I shall have to do, unless I can find some sort of employment.”

Mr. Mercer looked at her sympathetically.

He had met Lord Heywood’s widowed sister, who was older than he was and knew that she was not only in ill health but was one of those people who was always complaining and finding fault with everything and everyone.

In fact the last time he had come in contact with her he had said to his wife,

“I don’t believe that Lady Banton has ever said a nice thing about anyone in her life.”

“I suppose, poor dear,” his wife had replied, “she thinks that life has treated her badly and, of course, it had all started with her being excessively plain.”

Mr. Mercer had laughed.

But he thought now, looking at the girl opposite him, that her being so exquisitely lovely would not make her aunt feel any kinder towards her.

He leant across the desk, which had already been sold to pay for its late owner’s debts, to say,

“Surely there is someone else you could go to? What about that charming cousin who used to come here some years ago and ride with your father and then after your mother died helped him to entertain the guests at one of his shooting parties?”

“You must mean Cousin Elizabeth,” Minella said. “She married and is in India with her husband. She has not written to me so I presume she does not know that Papa is dead.”

“Could you not live with her?” Mr. Mercer asked.

Minella shook her head.

“I am certain that she would not welcome my imposing on her in India and you know as well as I do, Mr. Mercer, that I could not afford the fare.”

Because the one hundred pounds that he had put aside for her would not last forever, Mr. Mercer admitted silently to himself that this was the truth.

Yet he was deeply concerned as to what would happen to the girl he had known since she was a child and who had grown lovelier year by year with nobody to admire her in the quiet, unfashionable County of Huntingdonshire.

Lord Heywood had often complained,

“Why my ancestors settled in this benighted hole, God only knows! I can only imagine that the house attracted them for there is nothing else.”

It was in fact a most attractive seventeenth century Manor House and, as Lady Heywood had always said, it was comparatively easy to run.

But there was nothing in Huntingdonshire to attract the sophisticated friends whom Lord Heywood enjoyed having around him except for himself.

There was no doubt that Roy Heywood was born to be the centre of an admiring throng. He had a vitality and a charm about him that was irresistible.

Minella was not surprised when after her mother died her father was constantly being invited to parties in every other part of the country except for where they lived.

There the County gentlefolk seldom gave parties anyway.

Because she was too young to accompany her father even if anyone had wanted her, she had been obliged to stay at home in The Manor and wait for his return.

Sometimes it would be a long wait, but she had learnt to be pretty well self-sufficient and was quite happy as long as she had horses to ride.

Until the end of last year she had been very busy being educated.

“For Heaven’s sake,” her father had said to her, “stuff a little knowledge into your head! You are going to be very beautiful, my darling, but that is not enough.”

“Enough for what?” Minella asked.

“Enough to keep a gentleman amused, attracted and in love with you forever,” her father answered.

“The way you loved Mama?” Minella asked.

“Exactly,” her father replied. “Your mother always intrigued and amused me and I never missed anybody or anything else as long as we were together.”

This was not entirely true, for Minella could remember times when he had expressed disgust and irritation because they had no money.

He hated not being able to whisk her mother off to London, to go to theatres and balls and meet people who were as gay as themselves.

Even so The Manor had always seemed full of sunshine and laughter until her mother had died.

It had been a desperately cold winter and, however many logs were piled onto the fire, the house always seemed to have a damp chill about it.

Alice Heywood’s cough had become worse and worse until finally, unexpectedly and without warning, it turned to pneumonia and within two weeks she was dead.

To Minella it was as if her whole world had crashed about her ears and she knew that her father felt just the same.

When the funeral was over, he had said violently in a voice she had never heard from him before,

“I cannot stand it, I cannot stay here thinking your mother will walk into the room at any moment.”

He had left that same evening and Minella knew that he had gone to London to try to erase the memory of her mother and the happiness they had known in the past, which haunted her as well.

From that moment on her father had changed.

Not that he had become morose, gloomy and introspective, as another man might have done. Instead he had gone back to the raffish, devil-may-care self that he had been before he married.

Because he did not want to think of the wife he had lost, there were now inevitably other women in his life.

He did not talk about them, but perceptively Minella was aware of them and there were letters, some of them scented and some of them written in a flowery, extravagant uneducated hand.

Some he tore up and threw away as if they were of no interest to him, but others he read carefully.

Then a little later, as if he did not want Minella to find him out, he would say casually,

“I have some business to see to in London. I think I will catch the morning train. I will not be away for long – ”

“I shall miss you, Papa.”

“I shall miss you too, my poppet, but I will be back by the end of the week.”

But at the end of the week there would be no sign of him and when he did return Minella had the feeling that it was not because he wanted to see her but because he did not dare spend any more money.

Even so she did not realise until he had died that he had spent so much or had so many unpaid debts.

Roy Heywood, who, as many of his friends often said, was as strong as a horse, had died by a quirk of fate that seemed quite inexplicable.

He came home late one night and, as soon as she saw him, Minella realised that he had not only had an amusing time in London but a somewhat debauched one.

She had grown to know by the lines under her father’s eyes and also his general air of dissipation that he had been to too many parties and had had far too little sleep.

Alcohol in excess had never agreed with him and he was, she was sure, compared to his friends quite abstemious.

But then when he had told her in his more expansive moments about the parties he went to, she had learnt that champagne flowed like water and the claret he drank with his friends at the Club was exceptionally good.

The combination invariably somewhat affected his health until the fresh air, the exercise he took and the plain food they had at The Manor restored him to his natural buoyancy.

On this occasion, as soon as he had walked into The Manor, looking, Minella thought, dashingly raffish but at the same time not well, he held out his hand to her and she saw that it was wrapped in a bloodstained handkerchief.

“What has ‒ happened, Papa?”

“I caught my hand by mistake on a piece of loose wire, or it was something like that, on the door of the railway carriage. It is damned painful and you had better do something about it.”

“Of course, Papa.”

Minella bathed his hand gently and saw that there was a nasty jagged cut going deep into the flesh.

She could not help wondering if he had been a little unsteady when he had caught the train. Perhaps he had staggered or fallen in a way that he would never have done at other times.

Her father was always so agile on his feet and he was usually so healthy that, if he hurt himself out riding or in any other way, she always expected him to heal quicker than anybody else would have done.

So she was very perturbed the next morning when she saw that, despite her ministrations of the night before, his hand was now swollen and beginning to fester.

Although her father said that it was all nonsense and quite unnecessary, she sent for the doctor.

He had not thought it serious, but gave her a disinfectant salve to use on it, which she applied exactly following his instructions.

However, Lord Heywood’s hand grew much worse and at the end of the week he was in excruciating pain.

By the time he had seen a surgeon it was too late.

The poison had spread all over his body and only the drugs that made him unconscious prevented him from screaming out with agony.

It had all happened so quickly that it was difficult for Minella to realise that it was really true.

Only when her father had been buried in the quiet little churchyard beside her mother did Minella realise that she was now completely alone.

At first, having no idea of the financial mess that her father had left behind him, she had thought that she could stay on at The Manor and perhaps try to farm a part of the estate that was not already let to tenants.

It was Mr. Mercer who disillusioned her and made her understand that such plans were only daydreams.

The Manor itself was mortgaged and so was at least half the land.

By the time that the mortgages had been paid and she had seen the huge accumulation of debts that her father owed in London, she faced the truth.

She was not only alone but penniless.

Now, looking across the desk at the Solicitor, she said,

“I don’t know how to thank you, Mr. Mercer, for all your kindness. I have given you a great deal of work and I only hope you have paid yourself a proper fee as well as everybody else.”

“Don’t worry about that, Miss Minella,” Mr. Mercer replied. “Both your father and your mother were very kind to me when they first came to live here and it was through your father that I acquired a great many new clients for my small and not very impressive family firm.”

Minella smiled.

“Papa always wanted to help everybody.”

“That is right,” Mr. Mercer replied, “and I think that was one of the reasons why his creditors did not press him as hard as they might have done. Every one of them expressed deep and sincere regrets to me that he should have died so suddenly.”

As this was such a moving tribute to her father, Minella felt the tears come into her eyes. Then she said, “Papa always told me that, when he could afford to take me off to London, perhaps next year, his friends would look after me and give me a wonderful time.”

“Perhaps they would do so now,” Mr. Mercer suggested hopefully.

Minella shook her head.

“I am sure that it would not be the same unless Papa was there, making them all laugh at every party he attended.”

Mr. Mercer knew that this was the truth, but he merely suggested,

“Perhaps there is some kind lady who knew your father who would be willing to be your hostess, Miss Minella, and introduce you to the Social world that you should be moving in.”

“I don’t think I am particularly interested in the Social world,” Minella said reflectively, almost as if she was talking to herself. “Mama used to tell me about it, but I know I do not want to live with Aunt Esther, which would be very very depressing!”

Because there was a note in her voice that sounded as if she might cry, Mr. Mercer said kindly,

“You don’t have to make your mind up today, Miss Minella, when we have had so many depressing things to talk about. You can stay here at least until the end of next month. That will give you time to think of someone you can go to live with.”

Minella wanted to reply that she had been seriously thinking about it already.

She had lain awake night after night and unable to sleep going over and over in her mind the Clinton-Wood relations who were still alive and repeating to herself the names of her mother’s relations whom she had never met.

“There must be somebody,” she sighed, as she had sighed a hundred times before.

“I am sure there must be,” Mr. Mercer smiled encouragingly.

He rose to his feet and started collecting his papers that were lying on the desk in front of him to place them in the leather bag he carried.

It was old and worn and he had used it ever since he had first become a Solicitor in his father’s firm. Although his Partners and his office staff often laughed at it, he would not think of parting from something so familiar.

Minella rose as well and now they walked together over the worn carpet from the study where they had been sitting into the small oak-panelled hall.

Outside the front door Mr. Mercer’s old-fashioned gig was waiting, drawn, however, by a young horse, which would not take long to reach the small Market-town of Huntingdon, where his offices were situated.

He climbed in and the young groom who had been holding the horse’s head jumped in beside him.

They drove off, the wheels of the gig grinding over the loose gravel of the sweep outside the front door, which badly needed weeding.

Minella waved as Mr. Mercer drove away and then walked slowly back into the house.

As she closed the front door behind her, she thought it impossible that this was no longer her home. She did not own it and she had no idea where to go when she finally left it.

Except, of course, and the idea was like a menacing black cloud, to live with her Aunt Esther.

She could remember every word of the letter her aunt had written to her after her father’s death had been announced in the newspapers.

There was no warmth in the sentences her aunt had written. Then as a postscript she had penned,

“P.S. I suppose, as there are so few members of our family left, you will have to come and live with me. It will be an added burden but then, as I have had nothing else in my life, I am used to them.”

A burden!

The words seemed to haunt Minella.

With a pride that she had never realised she had, she had longed to retort that she would never be a burden to anybody.

‘And why should I be?’ she argued with herself. ‘I am young, I am well educated, I am supposed to be intelligent. There must be something I can usefully do to earn a living.’

There was no answer to that question.

As she then went back into the study, she remembered that, while she was talking to Mr. Mercer, she had thought that when he left she must take her father’s personal papers out of the desk and destroy them.

She had no wish for the newcomers to The Manor, who had just bought it for quite a reasonable sum with a great deal of the furniture as well, to pry into the personal affairs of the late Lord Heywood.

Minella was well aware that when the villagers, the farmers and their few neighbours in the vicinity of The Manor talked about her father, it was either with admiration because they wished that they could be as dashing as he was or with disapproval because of the way he enjoyed himself so much in London.

The stories of the smart and fashionable people who he associated with had inevitably reached the County sooner or later.

‘It is not their business.’ Minella had thought.

But she knew that if there were letters lying around they would read them and if there were bills they would ‘tut-tut’ over them.

If there was anything like a ball programme, a bow or a ribbon, a glove or a scented handkerchief, it would feed the tales they were already repeating about her father.

She knew what they were thinking by the way people in the local shops eyed her when she came in through the door.

She had not missed the note of irrepressible disapproval in the Vicar’s voice as he had read the Burial Service.

The old Vicar was a simple Godly man and, while he had always been grateful for the generosity her father had shown him and the fact that he never had to beg in vain, he had not approved of the life his Lordship had led since his wife had died.

Her father had laughed when she had told him that the village talked of nothing else but the gaieties that kept drawing him to London.

“I am glad that I give them something to talk about,” he had said. “At least it is a change from turnips, Brussels sprouts, the weather and that the Church steeple is falling down.”

“Oh, not again, Papa!” Minella had then exclaimed, knowing how much her father had already contributed towards the repairs to the Church.

“The only answer is to let it fall down,” Lord Heywood had said, “and, as falling is what they think I myself am doing, perhaps it would be appropriate.”

Minella had laughed.

“They like talking about you, Papa, and I don’t know what topic they would be left with if you vanished out of their sight.”

But indeed he had vanished and she felt that the conversation in the village would have to revert to turnips and Brussels sprouts!

She sat down at her father’s desk and pulled open the top drawer.

There was the usual miscellaneous collection of unsharpened pencils, pens that were unusable, stubs of cheque books, a bent penny and two threepenny bits in which her father had drilled a hole after they had been used in the plum pudding at Christmas and which her mother had told him were lucky.

“I will put them on my watch chain,” he had said at the time.

But, of course, he had forgotten to do so.

Now they looked tarnished and so did the buttons, which had once ornamented the livery of a footman.

The previous Lord Heywood, her dear father’s uncle, had employed no less than three footmen and a butler to wait on him.

When her father came to The Manor, they had a very efficient couple to run the house, a Nanny for her, a valet for her father and an odd-job man.

First the odd-job man had gone, then the valet and, when the couple grew too old and had to retire, they had been left with just Minella’s old Nanny.

She had looked after Minella’s mother when she was a child and had been the mainstay of the house until she had died at the age of seventy-nine shortly before Minella’s mother had passed away.

Minella often thought that, if Nanny had been alive, her mother would not have become so ill for she would have been able to warm the house better than they had.

After that there had been only daily women. Sometimes there were two or three of them but, although they cleaned the place most conscientiously, they were always in a hurry to get back to their own families.

Now there was nobody.

After her father’s death, Minella had deliberately ignored the dust accumulating in the rooms that they did not use.

She told herself that there was no point in spending money that she could not afford and she could manage quite well on her own without any help.

She pulled out of the drawer a piece of blotting paper covered with ink drawings, threw it away and collected everything else into a tidy heap, meaning to put it all into a box.

She was not quite certain what she would do with it but she would keep at least the silver buttons with the family crest on them and perhaps if she could not earn any money, she might even be grateful for the two threepenny bits.

Then, as she realised there was nothing incriminating or anything to make any ‘Nosey-Parker’ curious, she shut the drawer and opened one of the side ones.

This was very different and was stuffed full of letters. She realised that her father seldom answered letters but put them in the drawer, not as keepsakes but because he meant sooner or later to reply.

She started to open the letters systematically, tearing up those that were out of date and no longer of any interest.

A typical example read,

“Dear Roy,

We are expecting you to stay with us for the Hunt Ball. You know you are the only person who can make it enjoyable! We are also relying on you to bring the house party safely down from St. Pancras Station – ”

Minella did not bother to read any more but merely tore up the letter and threw the pieces into the wastepaper basket.

There were many others written in the same strain with addresses embossed on the top of the writing paper and surmounted by impressive crests or coronets.

But every invitation made it clear that her father was invited because he made the party ‘go with a swing’ or, as one invitation written in a woman’s hand, said,

“The whole thing will be a complete failure unless you are there as usual to make us laugh and, as far as I am concerned, to make me very happy – ”

Minella tore up the letter quickly as she had the feeling that anybody reading it would put an interpretation on the words that she did not wish them to do.

Then, because she herself had no wish to pry into her father’s private affairs, she tore up one letter after another without even taking them out of the envelopes or, if they were loose, without reading them.

She was just about to do the same to the last letter in the drawer when the name on the bottom of it caught her eye, ‘Connie’.

She looked at it, thought that she did recognise the handwriting and then with a second glance she was sure that she did.

Constance Langford was the daughter of the Clergyman in the next village to the one in which they lived.

Her father was a clever intelligent man who should never have accepted a country Living but should have been a Don at a University.

Her mother had persuaded him to teach Minella a number of subjects that were beyond the capabilities of the retired Governess who lived in their own village.

It had taken Minella a quarter of an hour riding across the fields to reach the Vicarage of Little Welham and the Reverend Adolphus Langford made her work very hard.

She had first gone to him when she was just fourteen and had shared the lessons with his daughter Constance, who was three years older than her.

It had been more fun learning with another girl and Minella had been very proud of the fact that she was quicker to learn and on the whole much more intelligent than Constance.

Constance, when they were not in her father’s study, made it quite clear that she thought lessons were a bore.

“I think you are lucky to have such a clever father,” Minella said politely.

“I think you are lucky to have such a handsome and exciting one!” Constance replied.

“I will tell Papa what you said,” Minella laughed. “I am sure he will be very flattered.”

She had brought Constance home to tea and, as her father was at home, he made himself very pleasant, as he always did with everybody, and Constance had gone into ecstasies about him.

“He is so smart and so dashing,” she kept saying. “Oh, Minella, when can I come to The Manor again? Just to look at your father is thrilling!”

She had thought that such a gushing compliment was somewhat unkind to Constance’s own father.

She liked the Vicar and found the way that he taught her was efficient and stimulating, but she soon had the suspicion that Constance was being particularly nice to her so that she would invite her again to The Manor.

Because she had so few friends, Minella was only too happy to oblige.

Constance had the use of a horse when her father did not need it and so they would ride back together across the fields. When they reached The Manor, to please Constance, Minella would go in search of her father.

Usually he was in the stables or in the garden and, as it was quite obvious that Constance looked at him with wide-eyed admiration and listened to every word he spoke as if it was the Gospel, Lady Heywood had laughed and said,

“You have certainly captured the heart of the village maiden, Roy, but you must not let her or Minella be a bother to you.”

“They are no bother,” her husband replied good-humouredly, “and the girls of that age always have a passion for the first man they meet.”

“As long as she is not a nuisance,” Lady Heywood said.

“If she is, I shall look to you to protect me,” Lord Heywood replied.

He had put his arms around his wife and they walked away into the garden, completely happy, as Minella knew, to just be together.

A year later, Constance, or rather ‘Connie,’ as she would now called herself, saying that ‘Constance’ was too staid and dull, had gone to London.

She had written to say that she had found some very interesting employment, although it seemed to Minella that her parents were a little vague as to what it actually was.

Only once did she remember Connie coming home, or rather coming to The Manor, and that was after her mother had died.

Her father was back from London and feeling very depressed.

Connie had appeared looking, Minella now thought, quite unlike herself and in fact so different that it was hard to recognise her.

She had grown slim, tall and very elegant and was dressed so smartly that Minella stared at her in astonishment.

She had actually thought that the young lady standing at the front door was somebody from the County calling on them, perhaps to commiserate with her father over her mother's death.

Then Connie had asked,

“Do you not recognise me, Minella?”

There had been a little pause and then Minella had given a shout of excitement and flung her arms round her friend.

“How wonderful to see you!” she had exclaimed. “I really thought you had disappeared forever! How smart you are and how pretty.”

It was indeed true. Connie had looked very pretty with her golden hair that seemed much brighter than it had been a year ago.

With her blue eyes and pink and white complexion she looked every man’s ideal of the perfect ‘English Rose’.

Minella had taken Connie into the drawing room, wanting to talk to her and just longing to find out what she was doing in London.

Then two minutes after she arrived her father had come in from riding and after that it had been obvious that Connie wanted to talk only to him.

After a little while Minella had gone to make tea for them, leaving them alone, and only as Connie was about to depart did Minella hear her say to her father,

“Thank you, my Lord, for all your kindness and, if you will do that for me, I will be more grateful than I can possibly say in words.”

“I can think of a better way for you to express yourself,” Minella’s father had replied.

His eyes were twinkling and he was looking very dashing and, she thought, as if he had suddenly come alive.

“You will not forget?” Connie had asked eagerly.

“I never forget my promises,” Lord Heywood had replied.

He and Minella had then walked with Connie to where she had left her pony trap at the blacksmith’s forge.

“The reason I came here was to have my father’s old horse re-shod,” she had explained.

She had looked, Minella noticed, at her father from under her eyelashes as she spoke and Minella had known it had only been an excuse to come to The Manor.

Then Connie had driven away looking absurdly smart and somewhat out of place in the old pony trap.

As they had watched her go, Minella had been perceptively aware that her father was thinking what a very small waist Connie had and how tightly fitting her gown was.

Her neck had seemed very much longer than it used to be and she had worn her hat at a very elegant angle on her golden hair.

“Connie has grown very pretty, Papa,” she had said, slipping her arm through his.

“Very pretty!” he had agreed.

She had given a little sigh.

“I often used to beat Connie at lessons,” she had said, “but she beats me when it comes to looks.”

Her father had suddenly turned round to stare at her as if he had never seen her before.

He seemed almost to scrutinise her and then he had said,

“There is no need for you, my poppet, to be jealous of the Connies of this world. You have the same loveliness that I adored in your mother. You are beautiful and at the same time you look a lady and that is so important.”

“Why, Papa?”

“Because I would not have you taken for anything else!” her father had said fiercely.

Minella did not understand, but because she was so closely attuned to her father that she knew he did not wish her to ask him any questions. At the same time she was very curious to know what he had promised to do for Connie.

Now, feeling somehow that she was intruding and yet as if she could not resist it, she opened Connie’s letter and read,

“Dear, wonderful Lord of Light and Laughter,

How can I ever thank you for your kindness to me? Everything worked out exactly as you thought it would and I have been given the job and also I have moved into this very comfortable little flat which again thanks to your ‘pulling the right strings’ I can now afford.

I have always thought you wonderful but never so wonderful as you have been in helping me when I really needed it.

One day perhaps I will be able to do something for you.

Until then, thank you. Thank you.

Yours,

Connie.”

Minella read the letter and then read it again.

Then as she wondered what her father could have done to make Connie so grateful, she read for the third time,

“One day perhaps I will be able to do something for you.”

It was in fact too late for Connie to do anything for Minella’s father, but supposing, just supposing, her gratitude might extend to her?

Connie might find her some employment that would save her from having to accept the only invitation she had received from anyone, which was to live with her Aunt Esther.

She looked at the address on the top of Connie’s letter, but as she did not know London, it meant nothing to her, although she had the idea that Connie would be living somewhere in the West End.

‘If I was in London, there must be dozens and dozens of jobs I could do,’ Minella told herself. ‘I could look after children, teach them or even, although Mama might disapprove, serve in a shop.’

She had an idea, although she was not quite certain if it was not just her imagination, that shop girls were very poorly paid and had to work very long hours.

That might be true of the large shops that sold cheap goods and catered for the masses.

But there must be better class shops that would be pleased to employ somebody ladylike.

Minella smiled to herself.

‘I am sure Papa never envisaged that that attribute would be commercially useful,’ she told herself.

But why not? Why not indeed?

It was surely better to be employed because one looked like a lady rather than common, brash and perhaps not very prepossessing.

She went to the mirror to look at her face, thinking as she did so how very pretty Connie had looked when she had visited them nearly a year ago.

‘Pink, white, and gold!’ Minella reflected to herself.

Then she looked at her own reflection critically.

Her face was the perfect oval that her mother’s had been. Her eyes were very large and, because she was so slender, they seemed to fill her whole face and it was difficult to look at anything else.

Scrutinising herself as if she was a stranger, she felt that her eyes were unusual, perhaps even strange, because they were grey.

That was in some lights, but now they just seemed to take on the colours round them, especially when the sun was shining and there was a glint of gold in them.

At other times they were grey, the grey of a raincloud, except when her pupils expanded, and then her eyes would look dark or rather a deep shade of purple.

‘I wish I had blue eyes like Connie,’ Minella muttered to herself.

She looked instead at her small straight nose and the curve of her lips and decided that she did look very very young.

‘Perhaps nobody would give me a position of responsibility,’ she thought.

She wondered if there was anything she could do to make herself look older.

The way she did her hair was very simple. It was the fashion to heap the long tresses that every girl was very proud of on the top of her head in a riot of waves and curls.

Minella was aware that these styles were very often artificially contrived with hot curling irons and an elaborate arrangement of curling rags took their place at night.

She, however, had no need of such aids, for her hair waved naturally and curled at the ends, which almost reach her waist.

Because it was far too much bother to do anything else when she was busy or was with her father, she merely brushed her hair, as her mother had taught her to do, a hundred times.

Then she twisted it into a chignon at the back of her head and, having pinned it firmly into place, forgot about it for the rest of the day.

Her father was punctilious about her hair when they were out riding.

“I just cannot bear a woman to look untidy on a horse,” Lord Heywood had said over and over again.

To be quite certain that she did not upset him, Minella not only used dozens of hairpins to. keep her hair tidy out riding but also wore a hairnet.

Her hair was not the same vividly gold colour that made Connie’s hair catch the eye, but instead was as pale as the first rays of the dawn.

Sometimes it appeared silver, as if it had been touched by the moon, but in the sun it was the faint gold of newly ripening corn or of the first primroses peeping beneath their leaves in the hedgerows in spring.

‘I may look like a lady,’ Minella whispered to her reflection in the mirror, ‘but rather a dull one and I doubt if anybody in London would look twice at a little ‘country mouse’.’

Then, as if she could not bear to be depressed even by her own verdict on herself, she laughed.

As her laughter seemed to ring out in the empty room, her whole face was transformed.

Her eyes shone brightly and she looked, although she was completely unaware of it, very enticing. It was difficult to explain, but there was something exciting about her as there had been about her father.

It was the excitement that Pan might have had or perhaps one of the Fairies who Minella had always believed as a child lived in the garden amongst the flowers.

It was an excitement that was as ethereal as the trees in the woods, the mists over the streams and the stars when she could see them shining in through her window at night.

The stars had always had an attraction for her because her mother had once described to her how she was born just after midnight on New Year’s Eve.

Almost as soon as she came into the world, her father had opened the window to hear the churchbells ringing in the New Year and had picked her up in his arms and carried her to listen to them.

“I well remember,” her mother had said reminiscently, “seeing you and your father, my darling, silhouetted against the stars that filled the sky outside and I thought how lucky I was to have two magical people here on earth belonging to me.”

“I would like to touch a star and hold it in my hand,” Minella had said when she was a very little girl.

“That is what we all want,” her mother had smiled, “and perhaps one day, darling, that is what you will do.”

‘I have to believe Minella said now to herself, “that I was born under a lucky star and what one believes comes true.”

It was then that she made up her mind.

It was daring and was something that she would never have thought of in the past.

But she felt almost as if her father was beside her saying in his own way,

“‘Nothing ventured, nothing gained’!”

‘I will go to London,’ she decided. ‘I will see Connie and ask her to help me for Papa’s sake.’

As she spoke beneath her breath, but still audibly to herself, she knew that it was a very tremendous overwhelming decision and also one that was rather frightening.

At the same time it was a risk worth taking.

And what was the alternative?

Only to go tamely to the unutterable boredom of Bath and grumpy Aunt Esther.